9. Adaptations for Chronic Illness

Eating healthfully and being physically active benefit everyone. When it comes to chronic health conditions, the benefits can be especially valuable. In some cases, it may be possible to reduce medications or reverse a condition through healthy lifestyle choices. Change is not always easy though, and it’s usually incremental. Be patient. Feeling better may take time, but it’s worth the effort.

It’s prudent to properly eat and exercise according to any specific health issues you may have. In this chapter, we discuss some common conditions and various recommended adaptations. It’s always wise to discuss changes in dietary and exercise plans with your health-care provider. Your physician and health-care team are your allies and can help track progress and provide ideas for when you get stuck.

Joint Pain

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis. Achy joints, especially in your knees and hips, may keep you from wanting to move. But physical activity is highly recommended in these cases, and evidence indicates it can help prevent or slow osteoarthritis damage.

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis. Achy joints, especially in your knees and hips, may keep you from wanting to move. But physical activity is highly recommended in these cases, and evidence indicates it can help prevent or slow osteoarthritis damage.

Just a few minutes of moving your body can relieve pain, and a dedicated longer-term program can help keep joints heathier. Some people especially benefit from simple stretches in the morning while still in bed. For example, opening and closing hands, bending and straightening the knees, and gently twisting the torso from side to side can be helpful. If you have rheumatoid arthritis, exercise can help to relieve symptoms and improve day-to-day functioning.

A recent study showed that activity trackers can help those with arthritis and other musculoskeletal issues increase physical activity (see “Trackers Can Motivate People to Exercise”).

The Arthritis Foundation recommends range-of-motion and flexibility exercises, coupled with aerobic and strength-training exercises. Walking and water exercises are particularly easy on the joints, and aquatic resistance training may be able to slow or even stop the progression of knee osteoarthritis. Other low-impact choices are cycling or using an elliptical machine.

High-impact activities like basketball should be limited and hard surfaces avoided. If you’re new to exercise or unsure what’s right for you, work with your doctor and/or a physical therapist to design an exercise plan for your needs.

Dietary changes may help control arthritis as well. A Mediterranean dietary pattern (see Chapter 3) is rich in foods that have been found to help control inflammation. The omega-3 fatty acids in fish and nuts, the antioxidants in fruits, vegetables, and beans, and the fiber in whole plant foods all have anti-inflammatory potential.

Some people report that nightshade vegetables (eggplant, tomatoes, peppers, and potatoes) make their arthritis pain worse. If you suspect this is the case for you, try cutting these foods out of your diet. If symptoms don’t improve after two to four weeks, add them back in.

Your Heart

If you have cardiovascular disease (CVD), such as atherosclerosis (hardening and narrowing of the arteries), heart failure, high blood pressure, or a history of a stroke or heart attack—diet and exercise can help improve or manage your condition.

Exercise can help control weight and improve cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors like high blood pressure and blood lipids (triglycerides and cholesterol). Regular physical activity also may reduce the need for medications. Exercise improves quality of life in CVD and makes it easier to perform self-care tasks.

Even so, there are precautions a person with CVD should take. In high-risk CVD, exercise may not be recommended. While most people with CVD may be able to exercise on their own after seeking their doctor’s guidance, your doctor may recommend you exercise under supervision of trained health personnel, such as at a cardiac-rehabilitation center if you are at a particularly high risk. Both aerobic and resistance training are generally recommended for people with CVD who have their doctor’s approval to exercise.

A cool-down session immediately after exercise is especially important if you have heart issues, since most problems associated with exercise in CVD occur after exercise. Your doctor can tell you if any health conditions or medications you are on could cause problems with exercise.

Diet is key to controlling high blood pressure, keeping your arteries clear, and controlling heart failure. While the diet advice offered in Chapter 3 is a good guideline, some additional recommendations apply to certain cardiovascular issues. Everyone should limit saturated fat, but if you have high cholesterol, you should be especially vigilant. A reduced-sodium, high plant-food diet, like the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) plan described in Chapter 3, has been proven to improve blood pressure. People with heart failure should follow their doctor’s or dietitian’s sodium and fluid recommendations as closely as possible.

Diabetes

If you have type 2 diabetes or prediabetes, exercising and eating well are the best things you can do to help improve blood-sugar control, enhance insulin sensitivity (which makes your body’s cells more responsive to insulin), and reduce cardiovascular disease risk factors.

A combination of resistance training and aerobic exercise may be especially helpful in improving A1C (a blood test for average blood sugar) in people with type 2 diabetes. In some cases, a regular exercise program may even lead to your doctor being able to reduce your diabetes medication.

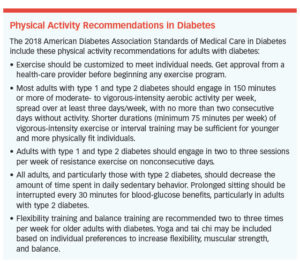

New research suggests high-intensity interval training (HIIT) may be another exercise option useful in type 2 diabetes management or prevention (see Chapter 2). General physical activity recommendations in diabetes are described in “Physical Activity Recommendations in  Diabetes.”

Diabetes.”

If you have type 1 diabetes, the American Diabetes Association considers exercise just as important for you as it is for the general population. Studies suggest many benefits of regular exercise in type 1 diabetes, such as improved cardiovascular health and improved insulin sensitivity, as well as reduced risk of long-term complications.

Effects on Blood Sugar

In the short term, exercise can help lower blood sugar because, in sustained moderate-exercise sessions, muscles take up glucose at almost 20 times the normal rate. Additionally, exercising muscle can absorb glucose on its own, without the use of insulin, and muscle cells also become more responsive to the effects of insulin with exercise. Just a single exercise session may increase insulin sensitivity for up to two or three days (and you should exercise regularly to maintain this effect). So, you’ll need less insulin to do the same job and you’ll reduce surges in insulin that can contribute to heart disease, high blood pressure, and other health concerns.

If you take insulin or sulfonylurea medications (such as glyburide and glipizide, which stimulate insulin release), you could experience hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) during exercise if adjustments aren’t made. Special precautions must be followed to ensure your blood sugar is in reasonable control before engaging in exercise, especially if you take insulin to control your blood sugar. Exercise performance seems to be best when blood sugar is maintained between 80 and 180 milligrams per deciliter.

is in reasonable control before engaging in exercise, especially if you take insulin to control your blood sugar. Exercise performance seems to be best when blood sugar is maintained between 80 and 180 milligrams per deciliter.

Generally, experts don’t recommend starting an exercise session if your blood sugar is higher than 250 mg/dL and ketones are present (which can be checked with urine test strips sold at pharmacies). Ketones are a chemical compound produced when a person with diabetes doesn’t have enough insulin available to use glucose for energy.

Also note that short sessions of high-intensity activity may make your blood sugar go up (regardless of which type of diabetes you have), due to the body’s release of certain hormones that raise glucose to help fuel physical activity. This is usually temporary, and within a few hours after intense exercise your blood sugar will come back down as glucose is used to replenish glycogen (glucose stores) in your muscles. Typically, you shouldn’t increase (but rather will likely need to decrease) your post-workout insulin dose in this situation. If you don’t take insulin, just realize it may take a little time for your blood sugar to come down after intense exercise, or you can cool down with some less-intense exercise to help bring your blood sugar back to normal.

Diabetes Complications

The longer you have had diabetes, the more likely it is you have developed microvascular complications (diseases of the smallest blood vessels) that could impact your exercise program. If you have conditions like retinopathy (eye disease), peripheral neuropathy (nerve disease), and nephropathy (kidney disease), you may require certain precautions during exercise and/or the avoidance of certain kinds of physical activity. Your health-care team can assess your condition and determine what types of exercise are appropriate and whether any restrictions are needed. For more information, see “Exercising with Diabetes Complications” at the American Diabetes Association website, diabetes.org. Older adults may face additional complications, and guidelines have been adjusted accordingly (see “New Diabetes Guidelines for Older Adults”).

The longer you have had diabetes, the more likely it is you have developed microvascular complications (diseases of the smallest blood vessels) that could impact your exercise program. If you have conditions like retinopathy (eye disease), peripheral neuropathy (nerve disease), and nephropathy (kidney disease), you may require certain precautions during exercise and/or the avoidance of certain kinds of physical activity. Your health-care team can assess your condition and determine what types of exercise are appropriate and whether any restrictions are needed. For more information, see “Exercising with Diabetes Complications” at the American Diabetes Association website, diabetes.org. Older adults may face additional complications, and guidelines have been adjusted accordingly (see “New Diabetes Guidelines for Older Adults”).

Osteoporosis

You can fight back against osteoporosis with good nutrition and physical activity and, in some cases, you may need to take bone-strengthening medications.

Bone Benefits of Exercise

In general, resistance training (two or three sessions per week) and weight-bearing aerobic activity (at least four sessions per week) are recommended to assist in maintaining and preventing bone loss. Resistance exercise causes muscle to contract against bone, and this stimulates the bone to become stronger and denser. In 1994, Miriam Nelson, PhD, and her colleagues at Tufts University published a ground-breaking study showing that postmenopausal women (ages 50 to 70) who lifted weights twice a week for a year gained an average of 1 percent of their bone mass, while those who didn’t exercise lost about 2 percent of their bone density, which is typical after menopause. Since then, other studies have confirmed that strength training is generally safe and can support bone health.

High-impact weight-bearing aerobic activity such as running or jumping rope may help improve bone mass more quickly compared with low-impact activity, such as a brisk walk. High-impact aerobic activity isn’t safe for everyone, though, so check with your health-care team first. Non-impact aerobic exercise, such as swimming, water aerobics, and bicycling, are good for your cardiovascular health, but don’t seem to place a sufficient load on the bone tissue to maintain or improve bone density.

Seek Expertise. If you have osteoporosis, get your health-care team’s guidance, including consulting a physical therapist experienced in osteoporosis, to discuss the best exercise program for you. A physical therapist also can assess kyphosis (an overly rounded back) and determine if there are exercises you should avoid. Expert instruction in correct technique for resistance training is especially important for those with poor bone health.

Eating for Better Bones

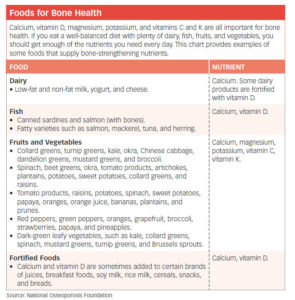

The National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends you get a well-balanced diet with plenty of dairy, fish, fruits, and vegetables. These foods are rich in calcium, vitamin D, and other nutrients that support bone health. For a list of bone-building foods and nutrients, see “Foods for Bone Health.”

Dietary Precautions

Beans contain calcium, magnesium, and other beneficial nutrients, but they also contain substances called phytates, which block the absorption of calcium. To reduce the phytate level, soak beans in water for several hours, then drain. Wheat bran also contains phytates.

Very high protein diets can cause the body to lose calcium.

High-sodium foods can cause your body to lose calcium and can lead to bone loss. Whole foods are naturally low in sodium. If you are eating packaged processed foods, check the Nutrition Facts label for sodium content. A food is considered high in sodium if a serving provides 20 percent or more for the percent Daily Value. Aim to get no more than 2,300 mg of sodium per day.

While foods like spinach, rhubarb, and beet greens do contain calcium, they also are high in oxalates, which bind with their calcium so it’s less available to you. These foods are healthy choices but not a good way to get calcium.

Caffeinated drinks (coffee, tea, colas) and too much alcohol can contribute to bone loss. (Note: Less than 3 cups of coffee a day does not seem to be a problem.)

Eating a healthy diet that includes plenty of calcium-rich foods can compensate for any negative effects from the calcium-depleting foods in your diet, so don’t hesitate to enjoy generally healthy choices, even if they are not the best for bone health.

Embrace a Healthy Lifestyle

Staying the course for the long run is among the most challenging aspects of embarking on lifestyle changes. That’s true whether or you have a chronic condition or not. Charting your progress can help you stay motivated, whether it’s with an online tracking program, a wearable digital fitness tracker, or simply logging in a notebook. Beyond just tracking what you eat, drink, and do; notice how you feel emotionally and how you are sleeping.

Eating well and exercising impacts your overall well-being, providing you with more energy, better health, and greater enthusiasm for living. Remember, it’s not about perfection. There’s room for treats and pauses. A healthy lifestyle is about making wise choices the rule rather than the exception. Give yourself a chance and enjoy the journey.

The post 9. Adaptations for Chronic Illness appeared first on University Health News.