6. In the Event of a Heart Attack

Heart attacks happen to someone in the U.S. every 40 seconds. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a whopping 790,000 Americans suffer a heart attack each year.

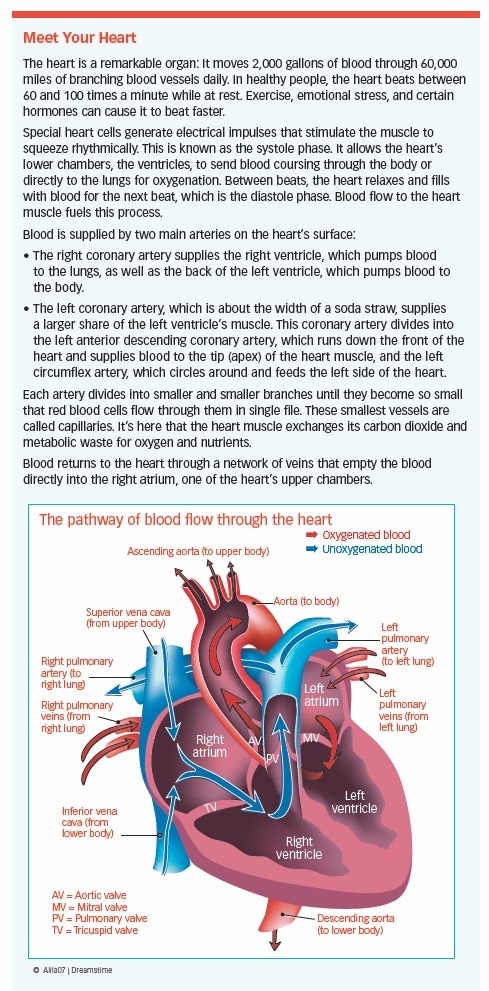

During a heart attack, the blood flow to the heart muscle is severely reduced or blocked. The coronary artery responsible for supplying the heart with essential oxygen and nutrients stops working and needs to get back on track—quickly! The longer the heart is deprived of oxygen, the more heart tissue that’s at risk of irreparable damage or death. The sooner blood flow can be restored, the better the chance of survival.

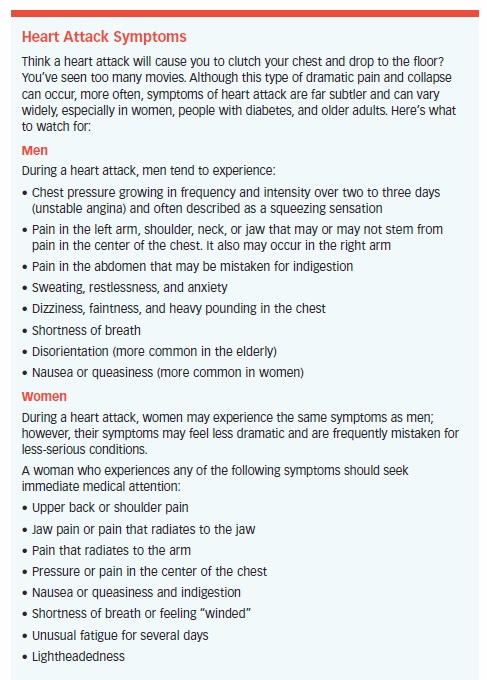

The scariest part? One in five heart attacks will occur without symptoms. In those who do experience symptoms, they may be mild (a feeling of having indigestion, for example, or feeling like a flu is coming on). Furthermore, 50 percent of those who die from a heart attack do so within an hour of noticing symptoms. In a mere six hours, damage to the heart muscle is often permanent and irreversible.

Surgery to open a blocked artery six or more hours following the first heart attack symptoms, however, has been successful in some. That’s why it’s essential to get medical help immediately after noticing any of the following signs:

- Chest pain

- Light-headedness, feeling faint or weak

- Pain in the jaw, neck, or back

- Discomfort in arms or shoulders

- Unexplained tiredness

- Shortness of breath

- Nausea or vomiting

Survival Rates: Increasing

On the plus side, the medical community knows a lot more about heart attack symptoms and treatments than in the past, meaning more people are surviving. For instance, research presented at the European Society of Cardiology 2017 Congress found that more women are surviving heart attacks than in prior years. In fact, only 6.9 percent of female heart attack victims died in the hospital in the past two decades; previously, that number was 18.3 percent. The reason for this success, researchers say, likely owes to improvement in diagnosing, taking seriously, and treating heart attacks in women. Men also are experiencing a decline in death rate, although the numbers are less dramatic.

Injury Site Determines Prognosis

Survival of a heart attack depends partly on what part of the heart muscle is affected and how much of it dies. Blockages that occur in the main artery on the front of the heart (left anterior descending artery) can be deadly, especially when they occur in the first one-third of the vessel. If 30 to 40 percent of the heart muscle is injured, or if the left ventricle is severely injured, the heart no longer will be able to pump effectively.

Aggressive treatment with medical therapy and early angioplasty or CABG has been shown to prevent more deaths or heart attacks than medical therapy alone. Similarly, aggressive medical treatment and preventive measures in patients with angina, heart rhythm disturbances, or heart failure lowers the risk of another heart attack or death.

During a heart attack, cardiologists say that “time is myocardium,” so treatment focuses on quickly restoring blood flow to the compromised heart muscle tissue.

Strategy may involve stenting or, less often, drugs to dissolve the blood clot. Once the patient is stable, doctors can determine whether a coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), further stenting, or medical therapy is the best approach to keep the coronary arteries open and prevent another heart attack. This may require transfer to a hospital with more experience treating heart patients.

Heart Attack Treatment

The first step in treating a heart attack is confirming you’re having one. In the hospital, any patient with symptoms of a heart attack is diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). An ECG and blood samples help determine whether the heart has been injured and if so, how severely.

Sometimes, the clinical signs and symptoms together with the ECG recording urge immediate treatment.

Although much progress has been made to identify high-risk patients, those at low risk still pose a diagnostic challenge for physicians. Some studies of coronary CT angiography (CTA) have confirmed the value of non-invasive technology for determining which patients with chest pain may be safely sent home. Others, however, found that CTA was more likely to lead to hospital admission and angiography.

How to Treat STEMI Patients

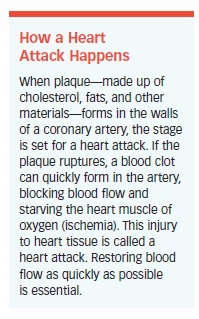

An ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), a type of heart attack, occurs when a plaque ruptures in a coronary artery, creating a clot that completely obstructs blood flow. A large area of the heart potentially may be affected. Complications can include heart failure, or a heart rhythm abnormality that can lead to cardiac arrest, or death.

Treatment guidelines focus on clinical decision-making at all stages, beginning with the onset of symptoms at home or work, systems of care to ensure that patients get immediate treatment, and the rapid restoration of blood flow through the obstructed coronary artery. Clot-busting drugs (as long as they’re safe for the patient) should be administered during delays, which may occur when a patient arrives at a hospital where percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is not performed. The patient should then be transferred to a facility where PCI can subsequently be performed, if needed.

Until recently, clots blocking coronary arteries were dissolved with thrombolytic agents given intravenously. The risk of bleeding in the brain is lower with PCI than with thrombolytic drugs, and when the procedure can be performed rapidly, it’s more effective in reducing the risk of recurrent heart attack or death.

Today, in medical centers with around-the-clock cardiac catheterization laboratories, all patients with STEMI are taken directly from the ambulance to the cath lab for PCI, avoiding the emergency department altogether. This helps ensure the artery is opened within the recommended 90-minute window. These quicker revascularizations result in fewer deaths and better quality of life for survivors.

At smaller and more remote hospitals, thrombolytic therapy may still be used with good results. However, when a patient doesn’t get relief from thrombolytic therapy quickly, the cardiologist will perform emergency or “rescue” PCI. The optimal timing of intervention has yet to be determined, but overwhelming evidence shows that taking action instead of waiting saves lives. Risk of death increases every 30 minutes that elapses before a patient with STEMI is treated.

In some patients, an intra-aortic balloon pump, Impella, or extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be used to reduce the work of the heart and increase coronary artery blood flow while preparations for PCI begin. This tends to help stabilize dangerously low blood pressure and prevent cardiogenic shock, which can cause organs to fail when they don’t get the necessary blood supply. Shock is a very serious, often fatal situation. Nevertheless, the combination of intra-aortic balloon pump and rescue stenting enables many patients to survive a heart attack.

Recovering from a Heart Attack

How well and quickly a patient recovers from a heart attack depends on a variety of factors. These include:

- The severity of the disease

- How much heart muscle was affected

- How quickly blood flow was restored

- The patient’s age, overall health, and fitness levels

The first 24 to 48 hours following a heart attack are the most critical. This is when the heart is most unstable. Most often, this time will be spent in a hospital where the patient is closely monitored. Having a heart attack increases your risk of other conditions, including a future attack.

Even a mild heart attack can cause permanent injury if not promptly treated. The greater the proportion of heart affected, the greater the risk of developing heart failure.

The good news: A full recovery is possible, even after a severe attack, as long as your condition is treated quickly.

Once at home, it’s essential to take your prescribed medication and modify your lifestyle. By taking extra good care of your heart, you’re less likely to suffer another heart attack, heart failure, or sudden cardiac death. Steps to take include exercising regularly to strengthen your heart muscle, decreasing your stress levels, implementing a heart-healthy diet, quitting smoking, and seeking treatment if you’re depressed.

Good news for those who carry a little extra weight: It could save your life. Researchers found that patients with low body weight who suffer a heart attack are at increased risk of dying. The reason? It’s thought that the absence of physiological reserve and fat stores hinder the body’s ability to handle the stresses caused by a heart attack.

Post-Heart Attack Medications

Recovering from a heart attack caused by a blood clot? You’ll likely be prescribed medications such as aspirin, clopidogrel (Plavix), ticagrelor (Brilinta), or prasugrel (Effient), a statin, and a beta-blocker to reduce the chance of dying from heart disease or needing bypass surgery. You also may be prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB. Patients who take proton-pump inhibitors, or PPIs, such as omeprazole (Prilosec) or esomeprazole (Nexium) to reduce gastric acid production, should be aware that PPIs may interfere with the beneficial effects of clopidogrel.

Doctors may advise that you:

- Take aspirin plus another antiplatelet medication when undergoing an invasive procedure.

- Take aspirin indefinitely and clopidogrel or ticagrelor for at least 12 months when undergoing medical treatment alone.

- Take ticagrelor or clopidogrel, whether being treated with medical therapy alone or also having an invasive procedure.

It’s important to take all medications as prescribed. Never stop taking them without a doctor’s permission. A study of more than 600,000 long-term aspirin users published in Circulation online found that those who stopped taking the drug without cause had a 37 percent higher risk of suffering a heart attack or stroke. The risk began to increase shortly after aspirin was stopped and didn’t decrease over time.

Other studies have shown that people who don’t fill their prescriptions after suffering a heart attack are far more likely to die within a year than those who fill their prescriptions and take the medications as prescribed. If you experience any type of side effects from the drugs you’re taking, contact your doctor immediately.

How to Prevent Sudden Cardiac Death

Sudden cardiac death (SCD)—also called cardiac arrest—occurs when the heart stops working abruptly and without warning. It can happen to those who appear healthy but is about four to six times more likely to occur in people who’ve survived a heart attack.

Despite its name, sudden cardiac death isn’t always “out of the blue.” Studies in which family members or bystanders were interviewed suggest that up to 80 percent of patients had symptoms that lasted up to several hours and were either misunderstood or ignored.

The risk of SCD is highest in the first 30 days after a heart attack and is most likely to affect patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction (the amount of blood pumped out by the left ventricle with each contraction) of less than 40 percent. Luckily, the risk drops continually over the following two-year period.

Cardiac arrest isn’t synonymous with heart attack as it doesn’t require blood flow through the coronary arteries to be blocked. Rather, cardiac arrest involves abnormal contractions due to a malfunction of the heart’s electrical system. That said, coronary artery blockages are one important cause of cardiac arrest.

The heart contains specialized fibers that conduct electrical impulses from its own “pacemaker” throughout the heart muscle in a well-coordinated fashion. These impulses are timed to make the heart muscle contract in a way that pumps blood effectively, squeezing it from the bottom to the top, where the main arteries leave the heart.

The most common heart rhythm disorder (arrhythmia) causing cardiac arrest is ventricular fibrillation, or VF. During VF, electrical impulses spread randomly through the heart, making the heart muscle quiver (fibrillate). It becomes unable to produce a contraction forceful enough to eject blood. The brain is the first to suffer the effects of absent blood flow, so loss of consciousness occurs within seconds.

Treatment must begin within minutes, or serious brain injury or death results. Shocking the heart with a defibrillator can stop the random electrical impulses flowing through it. Ideally, the heart’s natural pacemaker will then start up by itself, sending its electrical impulses down the proper paths and restoring the heart’s normal rhythm. While waiting for a defibrillator to arrive, the victim of cardiac arrest must receive CPR or damage to vital organs will inevitably occur.

A study published in the Journal of Athletic Training found that “survival declines by 7 percent to 10 percent for each minute that defibrillation is delayed.”

Those who’ve had a heart attack are at an increased risk of cardiac arrest. Their odds increase if they have a poorly functioning heart (low ejection fraction) that leaves behind an abnormally large proportion of blood in its ventricles after a heartbeat.

In general, the larger and more serious the heart attack, the more likely you’ll end up with a poorly functioning heart with a low ejection fraction and/or arrhythmia, even after emergency PCI or CABG.

After you’ve recovered from a heart attack, your cardiologist will tell you whether you’re at increased risk of cardiac arrest and will discuss treatment options. Beta-blockers may help you maintain a normal heart rhythm and prevent arrhythmias. Plus, new evidence indicates that omega-3 fatty acids, which are found naturally in fish and in supplement form, may help protect against sudden cardiac death.

The most effective treatment known to date, however, is an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). This small, electronic device is placed under the skin. Its job is to constantly monitor the heart’s rhythm and deliver a shock (energy) when it detects a rapid, abnormal rhythm, such as arrhythmias like ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia.

If an ICD detects ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, it will first try to correct the rhythm by “pacing” the heart with a burst of electrical impulses. If this works, the ICD will return to its monitoring mode. If not, it will send a more powerful electrical shock to the heart. Patients say it feels like a thump on the chest.

Most ICDs also act as a pacemaker if the heart rhythm becomes dangerously slow or irregular. An ICD is recommended if a person’s ejection fraction is 35 percent or less (a normal ejection fraction is 55 to 70 percent). As several clinical trials demonstrated, there is a significant decrease in the risk of death in those who receive an ICD after a heart attack.

ICDs have become increasingly popular as miniaturization has downsized these devices to the point where they can be placed under the skin, usually near the collarbone, without causing any discomfort. The newest ICDs are implanted in a procedure similar to cardiac catheterization and immediately tested to ensure they work properly.

ICD batteries last four to eight years, depending on how many times the device “kicks in.”

What Is Heart Failure?

Heart failure is a worrisome term—it implies the heart has stopped working. More accurately, heart failure means the heart isn’t able to pump enough blood

to fulfill the body’s needs. It can affect one side of the heart or both. In either case, the heart hasn’t stopped (as it does in a heart attack), but it does require medical help.

After a heart attack, some patients find that their heart doesn’t completely recover, and they are unable to resume normal activities without becoming fatigued or out of breath. These are the first signs of heart failure.

While the number and type of symptoms may vary from patient to patient, the primary symptoms are shortness of breath, fatigue, and fluid retention.

The heart attack may have caused some of the individual heart muscle cells to die. Over time, these permanently damaged areas of the heart become thinned and ineffective, or scarred and stiff. Either way, the heart no longer can pump as efficiently as it did before and is unable to meet the body’s demand for oxygenated blood.

Heart failure also can occur from high blood pressure, valve disease, or diseases that attack the heart muscle. Diabetes increases the risk, as do certain chemotherapy agents.

Heart failure often occurs gradually. In an effort to do its job, the heart undergoes a series of compensatory changes called “remodeling.” Remodeling is a vicious cycle; the weaker the heart becomes, the harder it tries to compensate for its inability to pump, and the less likely it is able to do so. In its early stages, heart failure may not produce many symptoms. But as it progresses, patients may experience some disturbing indicators.

Researchers of a study published in Neurology found that heart failure can impair brain function. When a group of 314 healthy participants underwent MRI brain scans, those with reduced cardiac output showed less blood flow to the left and right temporal lobes—the areas responsible for memory processing and where Alzheimer’s starts. Raising cardiac output with exercise and medications can help maintain both brain and heart health. Increasing cardiac output also may help prevent the progression of early memory loss.

Preventing heart failure, or managing it when you get it, is a complex process that may require diet, exercise, and other lifestyle changes, plus medication. When bypass or valve surgery can be used to restore blood flow to viable heart tissue, treatment may reverse heart failure. Some may need a new mechanical device to boost their heart’s pumping power.

Treatment is always individualized. The priorities are finding ways to help the heart pump more efficiently, relieving symptoms, and preventing the left ventricle—the heart’s main pumping chamber—from growing larger and weaker.

Today, many medical and surgical treatment options are available, allowing more people to prevent or delay the onset of heart failure after a heart attack. More effective medications and sophisticated new surgical approaches are helping people with the condition live longer, more productive lives.

Heart Failure Can Progress Quickly

Heart failure is traditionally classified by how well someone can perform the normal activities of daily life. Doctors call this “functional capacity.” Once diagnosed, most cases of mild and moderate heart failure can be treated to prevent heart failure from progressing.

Most patients’ symptoms will improve if they are treated appropriately and risk factors are eliminated.

NYHA Heart Failure Classification

As for diagnosing the condition, the New York Heart Association (NYHA) developed the most widely used tool:

Class I (No Impairment). Patients have heart disease but without resulting limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause undue fatigue, palpitation, dyspnea (shortness of breath), or angina pain (chest, jaw or arm discomfort).

Class II (Mild to Moderate). Patients have heart disease resulting in slight limitation of physical activity. They are comfortable at rest. Ordinary physical activity results in fatigue, palpitation, dyspnea, or angina pain.

Class III (Moderate). Patients have cardiac disease resulting in marked limitation of physical activity. They are comfortable at rest. Less-than-ordinary physical activity results in fatigue, palpitation, dyspnea, or angina pain.

Class IV (Severe). Patients have cardiac disease resulting in an inability to carry on any physical activity. Symptoms of heart failure or angina may be present even at rest. If any physical activity is undertaken, symptoms worsen.

ACC/AHA Classification

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) jointly use four categories to classify heart failure.

Each category is based on progressive stages. As such, the ACC/AHA classification includes patients both at risk for developing heart failure and those who have structural heart disease but no symptoms.

Their system was developed in response to the NYHA’s structure, which bases diagnosis on the amount of activity needed to create a patient’s symptoms. The downside of that approach? It’s subjective, assessing a person’s condition only at the time of the appointment. It doesn’t take into account changes that may occur between visits or take effect as the disease progresses.

The ACC/AHA system classifies patients based on disease progression and structural changes in the heart. Each stage is linked to treatments that are uniquely appropriate for it. Only ACC/AHA stages B, C, and D are comparable to the NYHA system.

Stage A. Patients are at high risk for developing heart failure but have no structural disorder of the heart. They also lack symptoms. Treatment focuses on eliminating or reducing risk factors through lifestyle modifications (diet and exercise, plus avoidance of tobacco, illicit drugs, and excessive alcohol). Hypertension, diabetes, or high blood cholesterol (see sidebar, facing page) levels should be treated appropriately. People with diabetes and/or confirmed coronary artery disease should be prescribed an ACE inhibitor or ARB, cholesterol-lowering drugs (statins), and/or aspirin.

Stage B. Patients have no apparent symptoms of heart failure but do have structural heart disease. Most have suffered a recent heart attack in which left ventricular function was largely preserved. Others have cardiomyopathy or valve disease. In addition to the lifestyle modifications and medications listed for Stage A, most patients should take an ACE inhibitor (or ARB) and beta-blockers. An implantable defibrillator may be advised in selected patients with low ejection fraction.

Stage C. Patients have structural heart disease and symptoms of heart failure, such as shortness of breath, fatigue, and reduced exercise tolerance. In addition to all measures appropriate for stages A and B, they should restrict salt intake, use a diuretic, and take an ACE inhibitor or ARB and a beta-blocker, or an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI).

Some may derive symptomatic benefit from digoxin, but this drug doesn’t prolong life. An aldosterone blocker, such as spironolactone (Aldactone) or eplerenone (Inspra), may be prescribed for left ventricular dysfunction following a heart attack.

If heart failure progresses, surgical intervention should be considered. In late Stage C (comparable to NYHA class III or IV heart failure), an aldosterone blocker may be advised. An implantable defibrillator is recommended for all patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 35 percent. Some patients may be eligible for cardiac resynchronization therapy (described later in this chapter).

Stage D. Patients are severely ill and require special medical and/or surgical intervention. Intravenous diuretics and vasodilators may be appropriate for hospitalized patients. These patients may be considered for a heart transplant, ventricular assist device (VAD), or an exploratory surgery or medication. End-stage patients who aren’t eligible for any of these extraordinary procedures may be referred for hospice care.

Heart Failure Meds

Standard medical treatment for heart failure has evolved into a sophisticated combination of therapies that change as the condition progresses. That said, the most effective medications and dosages vary widely for each patient.

Many heart failure patients require medication to treat other underlying conditions, such as diabetes. These drugs may interact with heart failure medications, causing side effects or worsening symptoms. Make your doctor aware of every medication you’re taking.

Medications Used to Treat Heart Failure

ACE Inhibitors. Until ACE inhibitors were developed, the diagnosis of heart failure came with a short life expectancy. Luckily, that’s no longer the case. These helpful drugs have greatly contributed to the improved prognosis for heart failure patients who receive treatment early in the development of their condition.

Here’s how they work: ACE inhibitors dilate blood vessels, allowing blood to flow more freely. This makes it easier for the heart to pump blood to the body. Originally developed as a medication for high blood pressure, ACE inhibitors are now known to do much more. They reduce heart rate, decrease the incidence of sudden death and heart attack, improve quality of life, enhance blood flow to the kidneys, improve sodium excretion, increase exercise tolerance, and prevent and perhaps even reverse detrimental remodeling. ACE inhibitors are considered to be an essential component of medical therapy for the treatment of heart failure.

Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers. Not everyone can tolerate ACE inhibitors. Some experience an intolerable cough, dizziness, taste distortion, or swelling of the face and throat. In these cases, an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) may be an acceptable substitute.

The effects of ARBs and ACE inhibitors are similar, but ARBs are less likely to produce a cough. No ARB is superior to ACE inhibitors, but if you have heart failure with a low ejection fraction and cannot tolerate ACE inhibitors, taking an ARB in addition to other medications is better than not taking an ARB at all. If you have heart failure with preserved systolic function, taking an ARB in addition to other medications may help keep you out of the hospital.

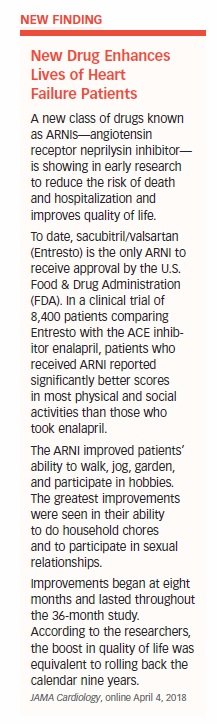

ARNIs. Cardiologists consider a new class of drugs called angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) to be among the most exciting developments in decades. The drug relaxes blood vessels and eliminates excess fluid and sodium in an entirely new way. In clinical trials, the first drug in this class, sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto), showed dramatic ability to reduce deaths and hospitalizations in patients with heart failure while improving their quality of life. Its benefits were so striking that the FDA expedited approval of the drug.

ARNIs are now recommended as a replacement for ACE inhibitors and ARBs in someone with:

- NYHA II and III heart failure

- An ejection fraction of less than 35 percent

Their use in these people can lower hospitalizations and mortality.

Beta-Blockers. Beta-blockers have been widely used to treat hypertension. Their ability to make the heart beat slower and less forcefully, however, was assumed to be harmful to patients with heart failure.

In reality, beta-blockers can be extremely helpful in improving the heart’s pumping ability. Studies showed that patients taking beta-blockers had up to 50 percent fewer deaths from fatal heart attack. Beta-blockers also were found to slow the progression of heart failure, improve NYHA functional class, and reduce the risk of hospitalization. They also may prevent harmful effects of ventricular remodeling and arrhythmias that can occur with heart failure. With respect to remodeling, beta-blockers can increase the ejection fraction and reduce the size of the heart. These biologic effects appear to reverse remodeling and return the heart toward normal.

Two beta-blockers have been approved for use in heart failure: carvedilol (Coreg and Coreg CR) and extended-release metoprolol (Toprol XL). Their most common side effects are dizziness, slow heart beat (bradycardia), shortness of breath, and fatigue. These usually can be managed by adjusting the dose.

Patients with decompensated heart failure or fluid retention should not use beta-blockers. Patients with severe diabetes, asthma, or peripheral vascular disease may not be able to tolerate beta-blockers.

Diuretics. As we learned earlier, diuretics rid the body of excess sodium and water. They’re used in heart failure to decrease swelling and relieve shortness of breath. Several varieties of diuretics exist, but the main type used to treat this condition is the loop diuretic, which owes its name to the part of the kidney it acts upon (the Loop of Henle). Drugs in this class include furosemide (Lasix), torsemide (Demadex), bumetanide (Bumex), and ethacrynic acid (Edecrin).

Specialists prescribe loop diuretics for 90 percent of heart failure patients but strive to use the lowest effective dose. A few patients with mild or moderate heart failure taking an ACE inhibitor and beta-blocker may not require diuretics. As heart failure becomes more severe, diuretic requirements often increase.

Digoxin. Digoxin helps the weakened heart contract more strongly. Clinical trials have shown that digoxin can improve symptoms, functional capacity, exercise tolerance, and quality of life in people with heart failure. In general, however, digoxin has no effect on survival.

Women, the elderly, and those with kidney failure are more likely to suffer toxic effects from digoxin and must use it with caution. However, digoxin appears to reduce heart failure-related hospitalizations, especially in patients with a very low ejection fraction (25 percent or less), so it continues to have a role in heart failure care.

Aldosterone Antagonists. Spironolactone (Aldactone) and eplerenone (Inspra) suppress the action of aldosterone, a hormone that causes the kidneys to retain sodium and water. Extra fluid in the body increases blood volume, which puts unwanted strain on an overworked, poorly functioning heart. In addition to helping eliminate excess water, these drugs have the ability to reverse left ventricular remodeling and improve survival.

Spironolactone can cause gynecomastia (breast enlargement in men). Eplerenone, on the other hand, doesn’t have the same effect. Both spironolactone and eplerenone can raise serum potassium levels, so these must be checked within a week or two of starting the drug. This is especially important for people with kidney failure who are more prone to developing high potassium.

Hydralazine Boosts Nitrates. Nitrates and hydralazine go hand in hand. Nitrates release nitric oxide, which dilates arteries and veins. Hydralazine helps increase their effectiveness. Together, they improve hemodynamics, reduce the workload of the heart, lower blood pressure, and relieve symptoms.

The combination of hydralazine and a nitrate (Imdur, Isordil, or Nitropatch) is useful in people whose kidneys are unable to effectively remove waste or who develop high potassium levels.

When either problem is a result of ACE inhibitor use, this combination may be substituted. The combination also is approved as add-on therapy for those who continue to experience symptoms of class III and class IV heart failure despite therapy with ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and spironolactone.

African Americans have been shown to derive particular benefit from the nitrate-hydralazine combination.

Intravenous Vasodilators. Intravenous therapy with nesiritide, nitroglycerin, or nitroprusside may be given to critically ill patients to dilate arteries and veins.

Nesiritide (Natrecor) is administered in the hospital or emergency department to patients with decompensated heart failure. Patients are given an initial bolus (large single dose) followed by a constant infusion. The initial dose and infusion rate is based on the patient’s weight. During infusion, blood pressure is monitored; the infusion is stopped if blood pressure drops significantly.

Nitroglycerin and nitroprusside can be started in the emergency department and continued in the intensive care unit. Nitroglycerin can be converted to oral medication for use after discharge.

Intravenous Inotropes. Intravenous inotropes are used in critically ill heart failure patients with shock, low blood pressure, or low cardiac output. They’re also given to patients awaiting a heart transplant and as continuous palliative therapy to improve quality of life for end-stage heart failure patients who wish to remain at home. Examples include dobutamine and milrinone.

Intravenous inotropes aren’t recommended for routine treatment of acute decompensated heart failure. The reason? There’s a lack of long-term benefit and an increased risk of complications such as hypotension (low blood pressure) and arrhythmias. They also tend to increase the risk of death during the period immediately after they’re started.

Other Heart Failure Medications

Anti-Arrhythmia Medications. Atrial fibrillation, or A-fib, is one of the most common arrhythmias, affecting up to 30 percent of patients with heart failure. This rapid, constant, unregulated contraction of atrial muscle cells prevents the heart from filling properly. The result: Ventricles contract more rapidly, dropping cardiac output up to 20 percent due to the loss of normal rhythm. It also increases the risk of a blood clot (thrombus), which can lead to a stroke, peripheral embolism, or pulmonary embolism.

Atrial fibrillation may resolve spontaneously, although it often requires the help of drugs or electric shock (cardioversion). If it continues to occur, antiarrhythmic agents such as amiodarone (Cordarone, Pacerone) or dofetilide (Tikosyn), or a catheter-based technique called ablation, may be used for prevention or treatment.

Ventricular arrhythmias are known to increase the risk of sudden death. Efforts to suppress these arrhythmias with drug therapy have been disappointing. Surgically implanted defibrillators that control heart rhythm often are recommended and are better than anti-arrhythmic drugs for preventing sudden death.

Anticoagulants and Antiplatelet Agents. The role of antiplatelet drugs, such as aspirin and clopidogrel, in heart failure remains unclear. These drugs inhibit the function of platelets—small, circulating blood cells that help form clots.

Aspirin, clopidogrel, ticagrelor, and prasugrel also significantly reduce the risk of heart attack in patients with coronary artery disease and reduce the risk of death following heart attack. So patients with heart attack and coronary artery disease should take aspirin and, in some cases, clopidogrel, ticagrelor, or prasugrel as well. It’s unclear, however, whether these drugs are effective in people with heart failure who haven’t had a heart attack or have no evidence of coronary artery disease, as clinical trials have been inconclusive.

Warfarin (Coumadin) is an anticoagulant given to patients at risk for blood clots. The value of warfarin in uncomplicated heart failure, however, is uncertain. That said, if a heart failure patient has experienced atrial fibrillation, either warfarin or a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC)—such as the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa), or the factor Xa (“10-A”) inhibitors apixaban (Eliquis), edoxaban (Savaysa), or rivaroxaban (Xarelto)—may be prescribed.

Helpful Supplements. As noted earlier, diuretic therapy can deplete potassium levels, leading to hypokalemia. It also can diminish magnesium, causing hypomagnesemia. Both conditions increase the likelihood of developing a life-threatening arrhythmia. Fortunately, these disorders can be easily corrected with potassium or magnesium supplements.

Hypokalemia is less likely to occur in patients taking ACE inhibitors and spironolactone or eplerenone. In fact, the opposite situation—high serum potassium levels—can occur with aldosterone blockers. Patients taking potassium supplements may need to stop or reduce their supplements when starting spironolactone or eplerenone therapy.

Statins. Although higher cholesterol levels are beneficial for people with heart failure, these patients do better when taking statins. Statins lower cholesterol, reducing heart attacks, and death. They have other beneficial effects, too, including the ability to reduce inflammatory factors and cytokines, improve endothelial function, and stabilize plaque. Heart failure patients who take statins have a lower risk of death and hospitalization for heart failure than non-statin users.

A Drug with Potential. Sildenafil, more commonly known as Viagra or Revatio, is a drug with great potential. Sildenafil offers a number of benefits in heart failure with pulmonary hypertension; specifically, it allows patients to breathe better and appears to limit the deterioration process.

Alternative Heart Failure Meds

Medications may not always be enough to manage heart failure. When that’s the case, it’s time to turn to other options. Bypass surgery or stenting, for instance, may be used to improve blood flow to the heart muscle. Defective heart valves also may be repaired or replaced via surgical procedures. These measures often help the heart regain its ability to pump properly and may cause heart failure symptoms to disappear.

When a large portion of the heart muscle is damaged beyond repair, or if the coronary arteries are extensively diseased, electronic devices, mechanical circulatory support systems, and surgical procedures offer hope for patients who don’t respond well to medication.

Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (Biventricular Pacing). In heart failure, interruptions in the heart’s electrical pathways cause the right ventricle to contract at a different rate than the left ventricle. Instead of a smooth, coordinated contraction, this lack of synchronization can reduce the heart’s ability to pump blood.

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is a minimally invasive method of making the ventricles work together in sync. It involves implanting a pacemaker, usually in the left front chest below the collarbone, and threading three electrodes into the heart through a vein. One is positioned in the right atrium, one in the right ventricle, and one in the left cardiac vein (to stimulate the left ventricle).

The electrodes are programmed to stimulate both sides of the heart simultaneously. The frequency and timing are adjusted to optimally coordinate the contraction of the atria and ventricles to produce a more efficient heartbeat. The result? Better blood flow, which improves heart failure symptoms and quality of life and reduces complications and risk of death. CRT may even reverse NYHA class II heart failure.

Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators (ICDs). As mentioned earlier, an ICD is a device placed under the skin that can benefit many heart failure patients at high risk of sudden death from a rapid, irregular, disorganized heart rhythm. In fact, about half of all heart failure patients die suddenly from cardiac arrest.

ICDs have been shown to be superior to anti-arrhythmic drugs in preventing sudden death. They also can be combined with a biventricular pacemaker in a single device if a patient meets the criteria for both. CRT plus ICD has been shown to be particularly effective in women.

Intra-Aortic Balloon Pumps. An intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) is a mechanical device inserted into the aorta through an artery in the groin. It’s goal: to control blood flow through the aorta, the body’s largest blood vessel.

Here’s how it works: A long, skinny balloon is located at one end of a catheter. The opposite end is connected to a computer console. The balloon pump is programmed to inflate and deflate in sync with the patient’s heartbeat. When the heart contracts, the balloon collapses, easing the force required for ejecting blood from the left ventricle. When the heart relaxes, the balloon inflates, increasing the diastolic blood pressure in the aorta.

Since coronary arteries receive most of their blood during diastole, inflation of the balloon improves coronary blood flow. Balloon pumps are used in the hospital’s cardiac intensive care unit as temporary circulatory support in patients with acutely decompensated heart failure and cardiogenic shock.

Ventricular Assist Devices. Ventricular assist devices (VADs) have brought perhaps the greatest change (and many would say improvement) to heart failure treatment. This mechanical heart-assist pump supports the heart in pumping oxygenated blood throughout the body. By doing so, a VAD can help prolong the life of a patient awaiting a heart transplant, hence their nickname “bridge to transplantation.”

VADs also can improve the quality of life for those who are unable to have a transplant. One-tenth to one-third of patients on a VAD and optimal medical therapy recover well enough to have the device removed. This means VADs also can be a “bridge to recovery.”

Here’s how VADs work: A surgeon opens the chest to connect the heart’s arteries and veins to a heart-lung bypass machine. The pump is placed inside the abdominal wall and connected to the heart with a tube. Then, the surgeon connects the VAD to the control unit of the pump that sits outside the body.

A battery power pack enables a VAD wearer to be out and about for several hours. This allows patients with advanced heart failure to become more active and improve their health and fitness.

VAD wearers waiting for a heart transplant are stronger and better able to withstand the stress of surgery when a donor heart becomes available.

Most VADs assist the left ventricle, the heart’s main pumping chamber. For heart failure patients who also have a weakened right ventricle, some VADs are able to support either side of the heart.

The latest VADs have success rates approaching that of heart transplantation, which remains a limited option due to the shortage of donor organs. The latest VADs also are implantable and have a single moving part known as an impeller that propels blood with a rotating turbine.

VADs are suspended by magnets, create no friction, and have no parts to wear out. They are highly biocompatible and resistant to wear and corrosion, making them ideal for permanent or long-term use. Their batteries can be recharged using household current.

Impella. Not to be confused with VADs, the Impella is a temporary (less than six hours) heart pump. It’s been used in patients with cardiogenic shock, severe heart failure, and high-risk percutaneous intervention (PCI).

The Impella consists of a long tube inserted by catheter through the groin, into the heart, and across the aortic valve, where it rests in the left ventricle. As the heart pumps, a tiny turbine—about the size of the spring in a ball-point pen—inside the Impella helps pull blood out of the ventricle into the aorta, where it is pumped into the circulatory system.

An Artificial Heart. A heart transplant is the only option for someone with advanced heart failure. Problem is, the wait for a donor heart can be long. In 2004, the FDA approved Syncardia’s Total Artificial Heart (TAH) for temporary use in patients eligible for heart transplantation and at risk for imminent death. To date, it’s been used in more patients than any other artificial heart.

The TAH completely replaces a failing heart and is designed to restore normal blood pressure and cardiac output. This results in improved circulatory function that enables other organs jeopardized by inadequate blood supply to recover. The result: a better ability to withstand and recover from a transplant.

Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. CABG may be used to improve blood flow and relieve symptoms in cases where CAD has caused significant impairment to blood flow to the heart muscle. This common procedure is discussed in Chapter 5.

Heart Transplant. Heart transplantation remains the gold standard for treating end-stage heart failure. More than half of all people who have a heart transplant survive for more than 12 years.

Unfortunately, the supply of donor hearts doesn’t meet demand. An estimated 20,000 to 70,000 people would benefit from a heart transplant, yet only about 2,000 receive one each year in the U.S.

Heart transplantation isn’t for everyone. It’s considered only when heart failure reaches NYHA class IV or ACC/AHA stage D, primarily due to the shortage of donor hearts. Patients are placed on the waiting list after careful evaluation to determine their overall medical condition and whether alternative therapies might be useful.

Screening determines whether the patient is likely to survive the operation and regain normal function.

Those being considered for a heart transplant must be capable of following a complex medical regimen and strict diet, quitting smoking, exercising regularly, and taking immunosuppressive drugs faithfully. The presence of other serious medical conditions or psychological issues excludes some people as transplant candidates, since medical compliance, emotional stability, and a strong support network of family and friends are critical to the operation’s long-term success.

The biggest medical obstacle in heart transplantation? Preventing the body from rejecting the donor heart. This is achieved through powerful immunosuppressive drugs that must be taken for life. These drugs can cause serious side effects, so their dosing must be carefully adjusted and monitored to get the maximum protection with the fewest downsides.

Transplantation is not the answer to the widespread problem of heart failure. No one expects the supply of donor hearts ever to match the demand. Plus, some people are considered unsuitable candidates for transplantation. This has spurred researchers to concentrate on the development of better VADs to someday eliminate the need for a heart transplant.

The post 6. In the Event of a Heart Attack appeared first on University Health News.