4. Fueling Activity

A healthful dietary pattern will give you the energy you need to optimally fuel activity, and the nutrients you need to get the maximum benefit from your exercise. If you don’t regularly fuel your body with nutritious foods, you’ll be at greater risk of fatigue, injury, and illness. Nutrients, such as carbohydrate, protein, fat, B vitamins, and antioxidants, in foods play very specific roles in supporting activity and/or recovery after activity. Understanding what these nutrients do and where they’re found can help you meet your needs and may even boost motivation to pass up nutrient-poor foods that could cheat you of good nutrition.

Macronutrients: Providing Energy

All foods are made up of three major nutrients (macronutrients): carbohydrate, fat, and protein. The macronutrients provide

energy (calories) to fuel our bodies and building blocks for growth and maintenance.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are chemical compounds called sugars, or chains of these sugars, that serve as the primary fuel for the human body. Every gram of carbohydrate provides the body with four calories. In order to fuel your body properly, it is recommended that carbohydrates make up 45 to 65 percent of daily calories.

The body breaks down or converts most carbohydrates to the sugar glucose. Your body stores glucose in limited amounts in your muscles and liver in a form called glycogen, as well as a bit in your blood, and draws upon these stores to fuel everything from breathing to running. An average-size person can store about 1,200 to 1,600 calories of glucose in muscles, 300 to 400 calories of glucose in the liver, and 100 calories of glucose in the blood. It’s important to consume enough carbohydrate on a daily basis to replenish these stores and meet the demands of physical activity.

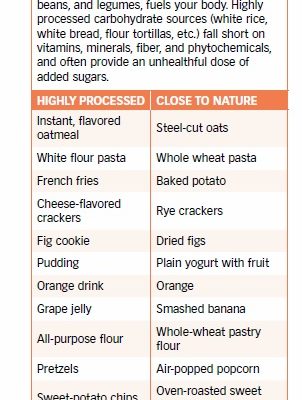

Fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and dairy products all supply carbohydrate. Highly processed foods made with refined flour—such as white bread, pasta, crackers, and muffins—are sources of carbohydrate, but these items typically fall short on the vitamins, minerals, and fiber found naturally in whole foods. Sugary foods, such as cookies, cake, candy, and soda, are especially low in nutrients and are often referred to as empty calories. Your body doesn’t run on carbohydrate alone, but rather with the help of countless other nutrients, including vitamins and minerals, that work behind the scenes to help convert carbohydrate to a form of energy your body can use. When you eat foods like whole grains, you get carbs, along with the vitamins and minerals necessary to use them, so opt for carbohydrate-rich foods in forms as close to nature as you can (see Box 4-1, “Better Carb Choices”).

Whole-food carbs not only provide more of what your body needs to produce energy, they also tend to be gentler on blood-sugar levels than refined-carbohydrate and sugary foods. Once glucose is in your blood stream, your pancreas releases insulin to help move the glucose into cells. Because whole foods are generally higher in fiber and move through your digestive tract more slowly, glucose from these foods is absorbed into your bloodstream more slowly and steadily. As a result, your body doesn’t have to release as much insulin to take care of the glucose, so your blood sugar is more stable and you feel better. Avoiding big spikes in insulin followed by large drops in blood sugar can help keep your appetite in check, too.

You have limited carbohydrate stores for exercise, and once you run out you either have to decrease your exercise intensity or stop altogether. If you’ve ever heard of “hitting the wall” during endurance exercise, that’s what this phrase refers to—the sudden fatigue and loss of energy when your carbohydrate stores fall short. Endurance activities like marathon running or long-distance cycling are more likely to lead to carbohydrate shortfalls, and those who participate in such activities may consume carbohydrate during exercise to prevent an energy shortage. It’s also important to note that without enough glucose, your body can’t burn fat for energy.

Dietary Fats

Fats (lipids) are an ingenious energy storage system. Humans, other animals, and even plants pack their excess energy into fat to save it for later. That’s why every gram of fat you eat provides nine calories—more than twice the calories in a gram of carbohydrate or protein. Dietary fats are necessary for the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K from foods. Fats also give foods a pleasant mouth-feel and carry flavor across our tongues (this is why low-fat ice cream just doesn’t feel or taste the same as full-fat). While the calorie-density of fats can lead to weight gain, eating some dietary fat is beneficial, and some kinds of fat are actually essential, since the body can’t make them on its own. It’s recommended that 25 to 35 percent of your daily calories come from fats.

Your body is always using a combination of carbohydrate and fat to fuel activity. The particular combination used depends on the intensity and duration of activity, as well as your fitness level. As you become more fit, your body is able to tap into your fat stores sooner, so you are able to exercise at a given intensity for a longer period of time.

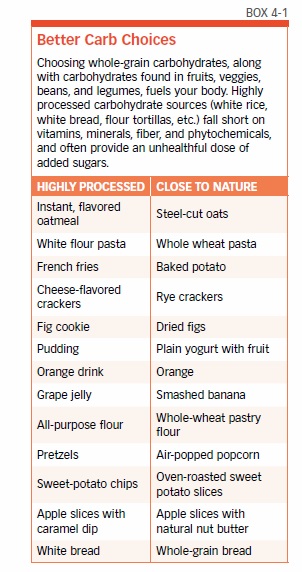

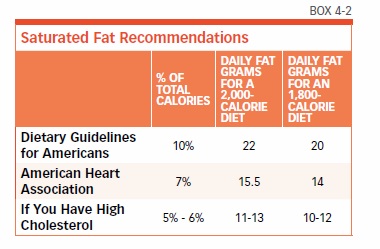

There are different kinds of fats, but they can all be classified as either saturated or unsaturated. Saturated fats (found in animal products and some vegetable oils, like palm and coconut) have been linked to increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and all major medical organizations recommend limiting saturated fat intake to 10 percent of daily calories or less, which is about 22 grams of fat daily for a 2000-calorie diet (see Box 4-2, “Saturated Fat Recommendations,” for more information). Americans currently get more than this recommended amount of saturated fat, mostly from “mixed” dishes containing meat, cheese, or both, like pizza, burgers, and tacos. Foods high in saturated fat also tend to be high in cholesterol. Until recently, it was recommended that people with high blood cholesterol levels restrict dietary cholesterol intake, but that recommendation has changed (see Box 4-3, “Is Cholesterol Back on the Menu?” for more information).

When unsaturated fats (whether mono- or polyunsaturated) replace saturated fats in the diet, risk of cardiovascular disease goes down. Monounsaturated fats (found in most vegetable oils, nuts, seeds, and avocados) seem to raise HDL (“good”) cholesterol and lower LDL (“bad”) cholesterol and triglyceride levels in the blood. Polyunsaturated fats (in plant oils, fish, nuts, seeds, and soybeans) can also help reduce LDL cholesterol. This class of fats contains the two fatty acids our body can’t make on its own: the essential fatty acids omega-3 and omega-6.

Eating patterns high in omega-3 fats have been shown to reduce inflammation after exercise and promote healing. That’s not all: One preliminary small study found that older adults (age 65 or older) taking supplemental omega-3 fats had increased synthesis of muscle protein compared to older adults supplementing with corn oil. Although fatty fish, like salmon, mackerel, herring, and trout, are by far the top source of the most potent omega-3 fats, you’ll get smaller amounts of omega-3 fats in grass-fed beef (typically sold at farmer’s markets or health food stores), walnuts, ground flaxseed, and chia seeds. Omega-6s, common in plant oils, are ubiquitous in the Western diet, since they are used often in processed foods.

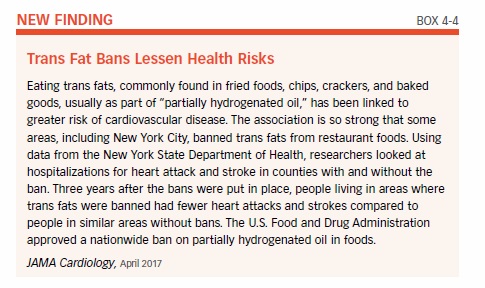

Man-made trans fat is by far the most harmful kind of fat. It not only increases cardiovascular disease risk, but also promotes inflammation, which can interfere with your body’s recovery from stress to muscles (see Box 4-4, “Trans Fat Bans Lessen Health Risks”). Foods rich in saturated fat, such as red meat and cheese, also may promote inflammation and chronic disease risk.

Since they are higher in calories than other macronutrients, all fats contribute more readily to unwanted weight gain (including inflammatory abdominal fat), regardless of whether they are classified as “good fat” or “bad fat” from a health perspective. Fortunately, a weight-loss program that includes regular exercise preferentially reduces fat stored in the abdominal area, so if you’ve packed on excess fat around your middle, physical activity can help.

Protein

Protein is used to build every cell and tissue in your body, including muscles, and is therefore essential to rebuilding after exercise. Body tissues are continually being broken down and replaced. In muscles, protein breakdown and repair is greatest after working out, especially after resistance training, such as lifting weights or using resistance bands. Making sure you have enough protein on board after exercise helps optimize this muscle rebuilding in the hours after exercise. Eating a protein-rich snack within an hour after exercise may be especially supportive, helping preserve muscle mass and strength. Consuming protein prior to aerobic or resistance exercise also may enhance the rate at which your body synthesizes muscle protein.

It is recommended that 10 to 35 percent of calories come from protein. You won’t have to think as much about timing protein intake around workouts if you spread your protein intake throughout the day. People have a tendency to eat the majority of protein at the evening meal, with little protein at breakfast. Research suggests that consuming protein at breakfast, lunch, and dinner may better support your ability to maintain muscle mass as you age. Increased protein intake may be beneficial to aging adults with limited ability to exercise, such as obese but frail older adults on a weight-loss diet.

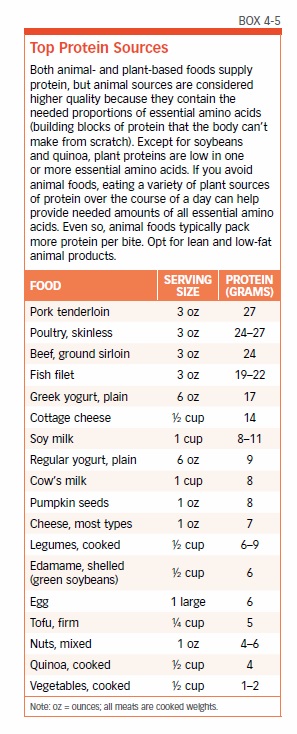

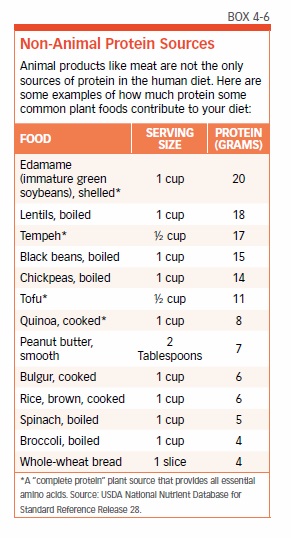

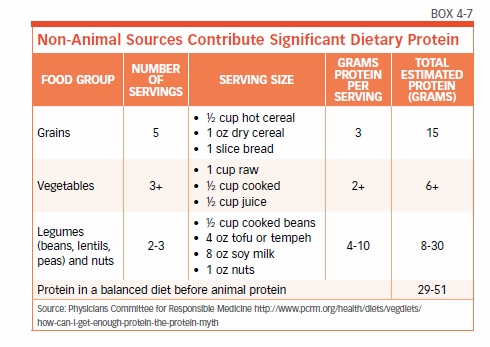

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for adults is 0.37 grams of protein for each pound you weigh (0.8 grams per kilogram). So, a 150-pound adult would need about 55 grams of protein per day (150 multiplied by 0.37 equals 55). For the protein content of common foods, see Box 4-5, “Top Protein Sources.” When trying to meet your protein goal, remember that not all of the protein in your diet comes from animal sources. Simply eating the recommended servings of grains and vegetables provides approximately 21 grams of protein, and adding beans, nuts, and foods like tofu and tempeh, bring that total much higher (see Box 4-6, “Non-Animal Protein Sources” and 4-7, “Non-Animal Sources Contribute Significant Dietary Protein”). Although it’s often assumed that people in America eat plenty of protein, approximately one-third of adults over age 50 fail to meet even the RDA for protein.

Micronutrients: Energy Conversion & Structure

Although we typically talk about the energy value of food in terms of calories, once you consume food, these calories are converted into a form your body can use to fuel physical activity and unconscious acts, such as breathing and keeping your heart beating. A number of vitamins and minerals are vital to this energy-conversion process.

B Vitamins

The B vitamins, including thiamin (B1), riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), vitamin B6, pantothenic acid, and biotin, do not provide energy themselves, but rather help facilitate the production of energy in your body from the food you eat. Without B vitamins, your body wouldn’t be able to convert food into energy. Two other B vitamins, folate and vitamin B12, play important roles in making red blood cells, which transport oxygen in the body, including oxygen needed in energy production.

So does this mean taking a B-complex supplement will give you more energy for physical activity? Probably not. Once you meet your body’s B vitamin needs, which generally can be accomplished with a healthy eating plan, any extra B vitamins are excreted in the urine. It’s important, however, to eat nutrient-rich foods, especially if you’re following a calorie-restricted eating plan for weight loss where every bite counts. B-complex vitamins are found in a variety of healthy foods, such as whole grains, low-fat dairy products, green leafy vegetables, nuts, seeds, eggs, poultry, lean meat, and seafood.

The B vitamins you’re most apt to fall short on as you age are vitamins B6 and B12. Unlike some of the other B vitamins, B6 and B12 are not required to be added to refined grains and aren’t as widely available in foods. Regular exercise, especially if vigorous, increases the body’s need for vitamin B6, and adults 51 and older need more B6 than younger adults.

The ability to absorb vitamin B12 from food lessens with age, and certain medicines (such as metformin and protein pump inhibitors) can decrease absorption even more. Additionally, vitamin B12 is only found in animal-derived foods, making it more challenging for vegetarians and especially vegans (who eat no animal products) to get enough. For these groups, consuming vitamin B12-fortified cereal or B12-fortified nutritional yeast can help meet requirements. The National Academy of Medicine (formerly known as the Institute of Medicine) recommends that adults over age 50 take an oral vitamin B12 supplement, although people with poor absorption may get more benefit from vitamin B12 injections. Your doctor can assess your vitamin B12 status with a blood test.

Minerals

Certain minerals are essential to powering your body. You need the mineral iron to move oxygen around in the body. It goes without saying that your body’s need for oxygen can increase significantly with exercise. The hemoglobin in red blood cells that carry oxygen as it’s transported around the body can’t do its job without iron. Iron deficiency, known as anemia, can lead to quicker exhaustion during a workout.

Men and postmenopausal women are at less risk of iron deficiency than younger women. Vegetarians and vegans are at greater risk of iron deficiency since iron from plant foods is not as well absorbed as iron from animal foods, like meat, fish, and poultry. Common plant sources of iron include fortified cereal, legumes, spinach, tofu, and raisins. Vitamin C helps boost absorption of iron from plant foods, so topping beans with tomato sauce or slicing strawberries onto cereal are smart moves to improve iron absorption.

Magnesium, calcium, and phosphorus are additional minerals that are essential for physical activity and/or energy production. Although people typically get more than enough phosphorus (soda can contribute to excess intake, which could weaken bones), many people fall short of consuming the estimated average requirements for magnesium and calcium. Magnesium is greatly involved in energy production. It helps break down glucose—primarily from that stored in muscle—into a form the body can use to fuel physical activity. Additionally, magnesium works with calcium to ensure normal muscle contraction: In order for your muscles to contract and move your body, they must have calcium, and in order for muscles to relax, they must have magnesium.

It’s important to make sure you’re getting adequate amounts of these minerals through a healthy eating pattern. Dairy products are well known as good sources of calcium, although the mineral also can be obtained from broccoli, kale, almonds, and calcium-fortified foods, such as orange juice, tofu, and milk substitutes. Nuts, legumes, and whole grains, such as brown rice and oatmeal, are good sources of magnesium. Minimize refined grains, though. Refining whole wheat to make all-purpose flour can reduce the magnesium content by over 75 percent, and magnesium typically is not replaced in the enrichment process.

Although some people think muscle cramps are caused by low levels of calcium and/or magnesium, this is unlikely to be true, as the body pulls these minerals from your bones to keep blood levels of these important nutrients stable.

Structural Nutrients

Strong bones help you to remain physically active and independent into old age. The vast majority of minerals in your body are contained in your bones. In general, the denser this network of minerals is, the stronger your bones are and the more protection you have against fractures. Physically active people generally have greater bone mineral density than those who are sedentary.

People reach peak bone mass around age 30. After that, your goal is to minimize losing bone mass as you age. Although both men and women are vulnerable to bone loss, hormonal changes in women speed up bone loss in the year or two before menopause and the five years or so after menopause.

Bone mass also is greatly affected by nutrition. If you don’t consume adequate calcium, your body pulls this mineral from your bones to supply your nerves and muscles with what they need. Other nutrients also are involved in keeping bones strong. Vitamin D improves the absorption of calcium from food and supplements. Vitamin K, magnesium, protein, and other nutrients are important in bone formation, too. Following a healthy eating pattern can help you get enough of all of them.

Vitamin D not only is important for strong bones, but increasing evidence suggests it’s also important for muscle strength and to help reduce inflammation. Your doctor can do a simple blood test to check your vitamin D levels—deficiency is surprisingly common. The jury is still out on how what level of vitamin D is optimal. The National Academy of Medicine considers levels above 20 ng/mL to be adequate to support bone health, while the Endocrine Society recommends levels above 30 ng/mL to support bone and muscle health. Observational studies suggest levels above 30 ng/mL also may better support immune function and reduce chronic disease risk. Until more information is available, consider your physician’s advice about what is best for you.

Although your body can produce vitamin D with adequate sun exposure, this ability decreases with age. Many other factors can reduce vitamin D production, including obesity, sunscreen use, darker skin color, and the angle of the sun in northern parts of the country during the winter months. According to the Vitamin D Council, if your shadow is longer than you are tall, you’re not making much vitamin D—and in the winter, this may be most of the day.

You also can get vitamin D in certain foods, including salmon, tuna, sardines, egg yolks, and vitamin D-fortified foods, such as milk, orange juice, and vitamin D-enhanced mushrooms. Some people have to take a vitamin D supplement, in which case vitamin D3 is the best form. Your doctor can guide you as to the best dosage based on your circulating vitamin D levels.

Phytochemicals: Protecting Cells

Free radicals, compounds that have inflammatory, cell- and tissue-damaging effects, form in your body every day as a result of normal body processes, such as breathing. Intense exercise is known to generate free radicals, but this is more than offset by the fact that exercise also up-regulates the body’s natural defenses against them. Another way to fight these pro-aging compounds is by eating plant foods.

Plants contain compounds called phytochemicals (plant chemicals) that have powerful impacts on the human body. Antioxidants are phytochemicals that neutralize free radicals, helping to keep cells healthy and reduce systemic inflammation and the risk of diseases, like cancer and cardiovascular disease. Vitamins C and E, while not phytochemicals, have antioxidant effects as well. Plant-based foods, including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and nuts, are good sources of a variety of antioxidants.

Although tens of thousands of phytochemicals in foods have been identified, scientists suspect many more exist. Some examples you may be familiar with are lycopene in tomatoes and watermelon (which reduce prostate cancer risk), and lutein in spinach and kiwi (to help prevent age-related blindness). Consuming whole foods is better than trying to take supplements of isolated phytochemicals, as many supplements are not proven to work, are poorly regulated, and could be harmful in high doses. Food components act in concert to produce beneficial effects, so isolating individual components into supplements could produce unsatisfactory or unexpected results (see Box 4-8, “Dietary Supplement Savvy”).

Choose Foods Wisely: Nutrient Needs Don’t Decrease with Age

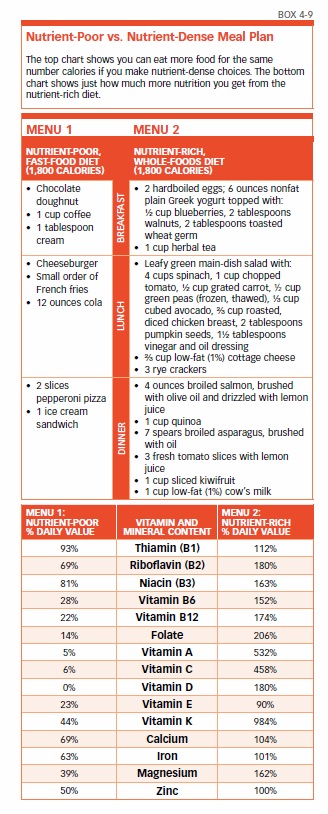

One challenge people face with aging is that the body’s calorie needs decrease, but nutrient needs don’t, so you have to get more nutrition from less food. (See Appendix I, “Food Sources for Nutrients of Concern for Low Intake in Older Adults.”) Highly processed and fast foods low in fiber and high in saturated fat, sugar, and salt frequently displace more nutritious foods in the American diet, and that can leave you short on important nutrients. As an example, look at the menus in Box 4-9. Although both menus have 1,800 calories, you’ll notice Menu 2 looks a lot more satisfying in terms of the volume of food.

Menu 1 is primarily made up of fast food, while Menu 2 is rich in whole foods, including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy, lean protein, nuts, and seeds. The benefit of such whole foods is evident when you look at their nutrient contribution, listed below the menus. Menu 1 falls short on numerous vitamins and minerals needed to support a healthy body and physical activity, while Menu 2 meets or exceeds daily vitamin and mineral goals for nearly all nutrients. Indeed, vitamin and mineral intake can vary greatly with food choices and can make a difference in how you feel and perform (see “Energy Density” in Chapter 3 for more information on nutrient-dense eating).

Timing Eating and Exercise

If you go into a workout or event inadequately fueled, you could end up feeling weak or run out of steam during the activity, or you simply may feel hungry, which can be distracting. In general, it’s best to avoid eating in the hour or so before exercise, so plan ahead to make sure you’re well fueled. Eating carbohydrate-rich foods prior to exercise may help improve your performance because it helps top off your muscle and liver stores of glucose (glycogen). This can be especially helpful in the morning, when your glycogen stores are depleted, and for intense activity when a greater proportion of carbohydrate is used for fuel.

It is generally not necessary to eat during exercise or athletic events unless the activity lasts more than 45 to 60 minutes. However, if you’re going on a two-hour bike ride, for example, you may need a snack halfway through as your glucose stores become depleted. Aim to eat about 30 grams of carbohydrate per hour of activity, such as a banana, an all-fruit nutrition bar, or other easy-to-eat items that contain minimal fat, fiber, and protein so they’re readily digested. If you’re exercising longer than three hours straight, you’ll need to refuel with more carbohydrate during the activity.

Immediately after exercise or an athletic event, blood flow to your muscles is increased and muscle cells are more apt to take up glucose to put into storage. Despite this, you don’t necessarily need to rush to eat a snack to refuel, unless your exercise sessions are intense, long, and frequent (at least daily). If you are such a rigorous exerciser, eating a good snack within 30 to 60 minutes after exercise will help restock glucose in your muscles and better prepare you for your next exercise session. An ideal snack at this time would be one high in carbohydrate with a bit of protein (about 15 grams), such as nonfat Greek yogurt with fruit or whole-grain crackers with low-fat cheese. The protein part of the snack helps your muscles take up glucose and helps repair muscle damage that occurs in the normal course of exercise.

On the other hand, if you space exercise sessions about 24 hours apart and exercise moderately for an hour or less at a time, you’ll have ample opportunity to refuel as long as you consume adequate amounts of calories, carbohydrate, and protein over the course of the day in regular meals and snacks. It’s not uncommon for people to overestimate how many calories they’ve burned during exercise and/or mistakenly think they need to refuel just because they’ve exercised. That can interfere with weight-control efforts. Appetite typically diminishes after a workout, so if you’re trying to lose weight, enjoy this hunger-free time.

Sports Foods and Supplements

Supplements and specialty sports foods, such as nutrition bars, energy gels, and protein shakes, are promoted to active people and athletes—and they’re big business, amounting to billions of dollars in sales annually. Before you use such products, especially on a regular basis, it’s important to understand the benefits and risks.

Specialty Sports Foods

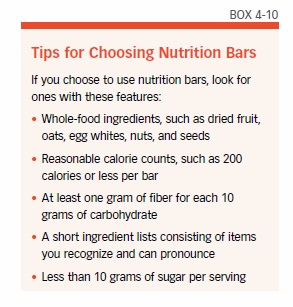

Unless you’re an endurance athlete spending more than 60 to 90 minutes in exercise or competing in long-distance events, you most likely don’t need specialty sports products, such as sports gels, energy chews, or gummies, and sports drinks (covered in Chapter 6). Sure, an energy bar can be more convenient than toting along a bruise-prone banana, but the bars often are packed with highly processed isolated proteins, fibers that can make you gassy (such as inulin or oligofructose from chicory root), added sugars, and excessive calories—in fact, some top 300 calories. That can be bad news when paired with tempting flavors such as “chocolate brownie” and “salted caramel”—potentially leading you to eat them even when you’re not being active or when you’re not hungry (see Box 4-10, “Tips for Choosing Nutrition Bars”).

Energy gels and chews generally contain about 100 calories per serving. They’re commonly made of highly processed ingredients, added sugars, chemical preservatives, and caffeine. If you’re doing endurance exercise and need a carbohydrate boost, you may do just as well eating a 100-calorie box of raisins.

Ready-to-drink protein shakes are popular, too, but unless you’re a competitive bodybuilder, most likely you can get plenty of protein from regular food. Protein shakes and drinks typically contain highly processed ingredients and often contain artificial flavors and sweeteners. If you’re struggling to take in enough calories or protein due to a poor appetite, consult a registered dietitian nutritionist.

Protein Powders

Many gyms and nutrition stores, as well as supermarkets, sell protein powder supplements that can be mixed into water, juice, milk, smoothies, or other beverages. Most commonly, the protein powders are made of whey, casein, egg, or soy protein, although alternative vegan (non-animal) sources, such as pea and hemp protein powders, are increasingly available. Both whey and casein are from milk. Whey is from the liquid portion of milk when it’s coagulated (to make cheese, for example), and casein is in the solid portion (curds).

Whey protein supplements have won favor with some athletes because whey protein is absorbed more quickly in the body than casein, and research suggests whey protein may be more effective than casein for increasing muscle size and strength for those doing resistance training. Even so, remember that the body can only use so much protein—any extra is broken down for energy, and excesses can be stored as fat. Breaking down protein requires the help of your liver and kidneys, so the burden of excess protein could pose a problem for those with kidney or liver disease. For others, protein supplements simply may be wasted money. Remember: The majority of physically active people easily can meet their protein needs with food.

Dietary Supplements

Dietary supplements come in many forms, including tablets, capsules, and powders. According to a recent consumer survey, 58 percent of Americans take dietary supplements. By far, multivitamins are the most popular dietary supplements among the general population, followed by vitamin D, vitamin C, and calcium. The most popular sports nutrition supplement is protein powder. Although countless dietary supplements are promoted to athletes, few actually have been shown to enhance performance, and even if there is a positive effect, it’s typically relatively small.

Besides concerns about unproven benefits, some supplements have quality-control problems, such as not containing the amount of the active ingredient declared on the label. Supplements also may be contaminated with substances banned by athletic groups, such as steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs. Typically, the contamination is due to poor manufacturing processes, but sometimes supplements are deliberately adulterated by manufacturers. The buyer of dietary supplements must be wary of such issues.

Performance-Enhancing Foods

Some natural foods are thought to enhance performance. Beet (or beetroot) juice, for example, has increased in popularity among athletes in recent years. Beets are naturally high in nitrate, which can be used in the body to produce nitric oxide. Nitric oxide relaxes blood vessels, helping to lower blood pressure. It also may boost oxygen levels in your blood to help skeletal muscles work more efficiently.

In one small study, recreational athletes drank about 17 ounces of beet juice per day for six days and did moderate- and high-intensity cycling. Compared to drinking a placebo beverage, athletes drinking beet juice had a lower demand for oxygen during moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and could exercise longer at a higher intensity before reaching exhaustion. Other research suggests increased dietary nitrate may improve performance in resistance exercise, and beet juice also may be helpful for those exercising at high altitudes since it can help blood vessels relax, enabling them to better deliver oxygen to tired muscles.

There’s a flip-side to nitrates in food, however. Nitrates are added to processed meats like sausage and bacon to preserve them and prevent the growth of dangerous bacteria. High nitrate intake has been shown to result in increased production of N-nitroso compounds in the body, which contribute to cancer risk. The acceptable daily intake (ADI) of nitrate, according to the World Health Organization, is 3.65 milligrams per kilogram of body weight per day (mg/kg/d). The amount consumed in the cycling study was 4.16 mg/kg/d, which is a bit more than the ADI.

Whether the nitrates in vegetables like beets are as much of a risk as the nitrates in processed meats is still largely unknown. Further research is needed to determine if safety concerns are justified at doses and usage patterns shown effective for sports performance. In the meantime, moderation is likely best for beet juice.

The post 4. Fueling Activity appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 4. Fueling Activity »

Powered by WPeMatico