5. Exercise Routines

You’ve read the recommendations of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans in Chapter 2 and learned how to fuel your activity in Chapter 4, now it’s time to explore some exercise routines to get you started on the road to a longer, healthier life.

As discussed in detail in Chapter 2, aerobic and strength-training (resistance) exercise are both important parts of your fitness regimen. Regular aerobic exercise helps make your lungs, heart, and cardiovascular system stronger and healthier, so you may have more stamina and reduced risk factors for chronic disease, such as elevated blood pressure, cholesterol, and triglycerides. Resistance training is especially important for slowing down the loss of muscle mass and strength that occurs with age, and for keeping bones strong. There are countless aerobic and strength-training programs you might choose on the path to fitness. Begin by warming up, end by cooling down, and, in the middle, try some of the exercise ideas discussed below.

Warming Up, Cooling Down

Warming up before exercise helps provide a safe transition to moving your body, and cooling down at the end of a session supports your body’s recovery after exercise. You should warm up before any type of exercise. Warming up helps gradually increase your heart rate and breathing, improving delivery of oxygen and fuel to working muscles. It also helps warm up your muscles so they’re ready to work, which helps reduce risk of injury and muscle soreness after exercise. Cooling down at the end of your exercise session helps you gradually decrease your body temperature, heart rate, and breathing, as well as reduce the risk of dizziness associated with abruptly stopping exercise. Keeping your arm and leg muscles moving during the cool down helps prevent blood from pooling in your hands and feet and can help reduce muscle stiffness after your session, too.

Warm Up

Regardless of what kind of exercise you’re going to do, take about five to 10 minutes at the beginning of your workout to warm up. Avoid static stretches (stretching to a challenging but comfortable position and holding it for several seconds) during the warm-up—save these for the cool down when muscles are warm. A few ideas of how to warm up include:

- Walk around or march in place while swinging your arms, along with some knee lifts and small kicks.

- Walk up and down some stairs a few times.

- Dance around your living room to a couple of songs.

- Mimic some of the same movements you’ll be doing during exercise, but at a slower pace and lower intensity, for example:

- Warm up for a walk by walking slowly at first, then gradually increase your pace.

- If you’re going to play tennis, hit some easy groundstrokes from the middle of the court. Or, if you are going to play a round of golf, warm up by taking some easy swings on the driving range.

- If you are going to do wall push-ups, go through the wall push-up motion but stand closer to the wall, move more slowly, and do fewer repetitions than you’ll do during the exercise session.

Cool Down

Take about five to 10 minutes at the end of your workout to cool down. It’s a bit like the warm-up but in reverse and can include some flexibility stretches and relaxation breathing. Stretching at the end of your cool down may help increase your range of motion in future exercise. Stretch the same muscles you worked during your exercise session.

Aerobic Exercise

Getting at least 150 minutes a week of any activity that gets your heart pumping is a highly effective way to help you be healthy, energized and active now and in the future. (See Chapter 2 for details.) Any activity works, from everyday tasks and recreational activities to organized exercise opportunities, as long as you get your heart rate elevated and keep it there for at least 10 minutes. There is an aerobic activity to fit every taste, budget, and fitness level, from dancing to dunking, high-intensity boot camps to hula-hooping. If you think aerobic exercise is limited to aerobics classes, Jane Fonda workout tapes and jogging, the few examples in this chapter may provide a fresh perspective.

Measuring Effort

To get the most benefit from aerobic exercise, you should exercise hard enough and long enough to get your heart rate into the target range for your age. There are different methods for assessing how hard you’re working. Two of them are described here:

- Target Heart Rate: Your heart rate is the number of times your heart beats in one minute, and you can check it by taking your pulse (see Box 5-1, “How to Take Your Pulse”). Alternately, you can purchase a heart-rate monitor to wear during exercise (discussed in Chapter 8), so you don’t have to stop to take your pulse. Many of the exercise machines in gyms can monitor your heart rate for you. For example, pulse sensors are typically built into the handgrips of elliptical machines.

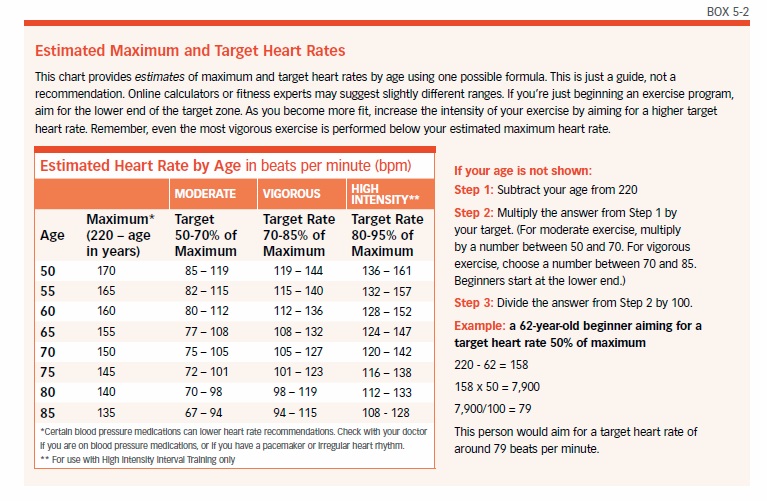

The target heart rate you should aim for during exercise is a percentage of your maximum heart rate. Box 5-2 will give you some idea of what your maximum and target heart rate may be. Keep in mind these numbers are merely an estimate.

The target heart rate zone covers a fairly broad range. How fit you are will determine your target range. If your fitness level is currently low, you may aim to exercise around 50 to 60 percent of your maximum heart rate, but if you are more fit, you may be able to maintain a higher percentage, such as 65 to 75 percent of your maximum heart rate during exercise.

Certain high blood pressure medications lower the maximum heart rate and, in turn, the target heart rate. If you’re taking a blood pressure medication, ask your doctor if you need to use a lower target heart rate. If you have a pacemaker or an irregular heart rhythm (atrial fibrillation), the target heart rate method is not advised.

- Talk Test: A simple talk test will give you an idea of whether you’re exercising in your target heart rate zone or not. If you can carry on a conversation without any difficulty, you may be exercising below your target zone. If you can carry on a conversation but need to stop speaking now and then to catch your breath, you are probably in your target heart rate zone. If talking is difficult or impossible, you may be overdoing it and may need to ease up a bit.

Aerobic Fitness Walking

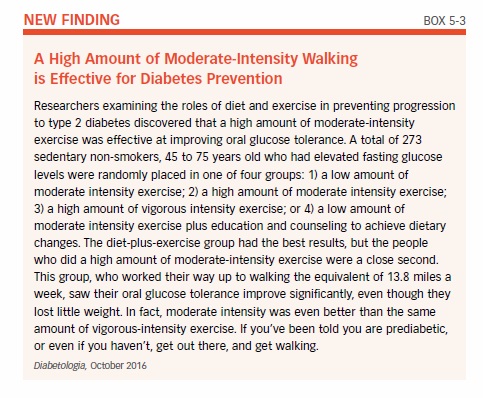

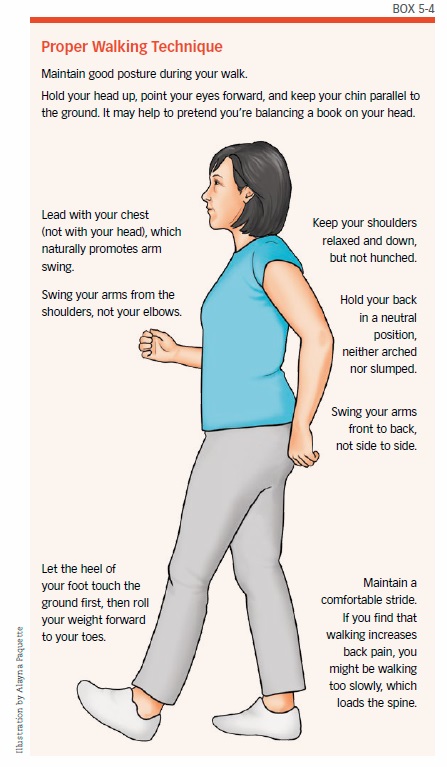

Walking is something people typically do every day as part of regular activities, but it can have a powerful impact on your health (see Box 5-3 “A High Amount Of Moderate-Intensity Walking Is Effective For Diabetes Prevention”). Turning walking into aerobic exercise just requires increasing the intensity and pace for a finite period of time, such as 30 minutes, and repeating the session on a frequent basis, such as once a day. Although walking is something you’ve likely been doing since you were a toddler, it’s a good idea to brush up on proper walking techniques for fitness walking (see Box 5-4, “Proper Walking Technique”).

Start at a distance and speed that is comfortable for you then add five minutes a week until you are at your walking goal. Walking is inexpensive, simple, and carries a low risk of injury, yet it can be effective for improving cardiovascular fitness if done regularly and at a high enough intensity.

The general structure of a walk is as follows:

- Warm up by walking slowly.

- Increase your speed to a brisk walk, which means a pace that raises your heart rate but still allows you to speak and breathe easily.

- Cool down by walking at a slower pace.

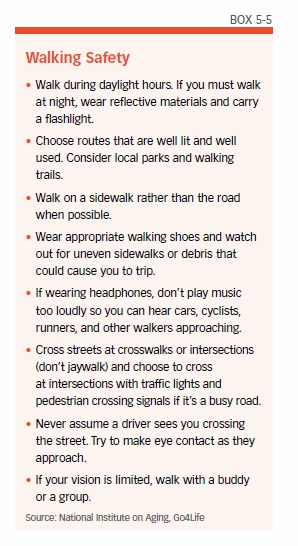

If you already are quite fit and want to get in even better shape by walking, you will have to increase your intensity, for example, by adding in hill walking, wearing a weighted vest, and/or by increasing your speed. For tips on walking safely in your community, see Box 5-5, “Walking Safety.”

HIIT it!

High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) has been used to train athletes for many years, but has recently grown in popularity for the general public. HIIT workouts involve repeated bouts of high-intensity effort, with recovery time between each bout. They improve both aerobic and anaerobic fitness, blood pressure, cardiovascular health, insulin sensitivity, and cholesterol profiles, and reduce abdominal fat and body weight while maintaining muscle mass. Part of the appeal of HIIT workouts is that you get all of the benefits of continuous endurance workouts in a shorter period of time (see Box 5-6, “HIIT Gets Older Adults In Better Shape, With Less Time Spent Exercising”). HIIT training can be easily modified for people of all fitness levels, and works with any kind of exercise, from walking, biking or swimming to elliptical cross-training and group exercise classes.

The intense work periods push your heart rate to 80 to 95 percent of your estimated maximal heart rate. The recovery periods typically last at least as long as the work periods and are usually performed at 40 to 50 percent of your estimated maximal heart rate. A HIIT session can last from 20 to 60 minutes. During the high-intensity interval, you should be able to carry on a conversation, with difficulty. The recovery interval should feel comfortable.

The ratio of exercise to recovery can vary, but 1:1 is typical. For example, you may perform three minutes of hard work followed by a three-minute recovery period of low-intensity activity. High-intensity bouts should not last more than eight minutes. Another popular HIIT training protocol is the “spring interval training method,” which involves 30 seconds of near full-out effort followed by four to 4½ minutes of recovery, repeated three to five times. HIIT workouts exhaust your body. One session a week, complemented by regular “steady state” endurance workouts, is probably enough. You can work your way up to two HIIT sessions a week, but be sure to spread them out to give your body the extra time it needs to recover from this intense exercise.

If you are typically sedentary, it’s recommended that you build a base fitness level before beginning HIIT training. Consistent aerobic training (three to five times a week for 20 to 60 minutes per session at somewhat hard intensity) for several weeks will get your muscles ready for interval training. This will also give you the proper exercise form and muscle strength you need to reduce the risk of injury.

The American College of Sports Medicine recommends that sedentary individuals, or those who smoke, have hypertension, diabetes (or pre-diabetes), abnormal cholesterol levels, obesity, or a family history of heart disease get medical clearance from a physician before starting any exercise program, including HIIT, as they may have an increased risk of heart attack during high intensity exercise.

Pool Exercises

No matter what your current exercise level, it’s likely there’s an aquatic exercise program for you. Exercising in a pool is easy on the joints and body tissues and suits a whole range of abilities and needs, but it’s an especially good choice for the elderly, people who are obese, those with orthopedic disorders (problems with muscles, ligaments or joints), or anyone rehabbing from a soft-tissue injury.

During land-based exercise, like jogging or other aerobic exercise that involves jumping around, the weight of your body repeatedly striking the ground is hard on the joints and can lead to joint or tissue injury. In the water, your body weight is reduced by up to 90 percent due to buoyancy, so the weight is taken off your joints even when you run or jump. But being lighter doesn’t mean you aren’t working hard. Water is 800 times as dense as air, so it provides plenty of resistance, allowing for high levels of energy expenditure with low levels of strain on the body. In fact, studies of deep-water running have shown that jogging or running in waist-deep water can get your heart rate up even more than running on land.

While swimming is probably the first thing to come to mind when most people think of exercise in a pool, there are many different kinds of aquatic exercise programs. Most are performed standing in waist- to chest-deep water (shallow water) or floating (deep water), usually with flotation equipment. The Aquatic Exercise Association (AEA) promotes everything from cardio programs geared to every fitness level, dancing, water walking, high-intensity training, and deep-water running, to programs that focus on abdominal and core muscles, special programs geared to those with arthritis, and even tai chi and yoga moves done in warm water.

A 2017 study that looked at the effects of aquatic exercise on body composition and walking speed in post-menopausal women with mild knee osteoarthritis found that four months of high-intensity aquatic resistance training led to weight loss and improved walking speed. Most of the women gained the weight back after the program ended, but the improvement in walking speed was still there at the 12-month follow-up.

The AEA recommends that all individuals obtain physician approval prior to initiating exercise or when significantly altering an existing exercise program.

Muscular-Strength Exercises

The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans and the American College of Sport Medicine (ACSM) recommend all adults perform muscle-strengthening activities at least two days a week. Muscles are strengthened by exercising them against external resistance, which is why strength training is often called resistance training. While the idea of a toned, muscular body motivates many people to lift weights or hit the machines at the gym, the fact is that working toward stronger muscles has numerous health benefits. Some of the great things resistance training can do for you include:

- Preserve the lean muscle mass typically lost as you age

- Reverse loss of muscle due to aging

- Strengthen connective tissue around the muscle to

prevent injury - Maintain ability to perform activities of daily living in advanced age

- Strengthen bones to help prevent osteoporosis

- Lower body fat

- Decrease blood pressure

- Improve cholesterol levels

- Reduce the stress placed on the heart while lifting a load

- Decrease the risk of heart attack.

Anything that provides something for your muscles to push against (resistance) can be used to increase muscle strength, whether it’s free weights, machines, elastic bands, or your own body weight. You can even use soup cans or milk jugs filled with sand. According to the ACSM, machine-based exercises are regarded as safer for beginners.

Unless you plan to work different muscle groups on different days, an exercise session should include eight to 10 exercises that target the major muscle groups (legs, hips, chest, back, abdomen, shoulders, and arms). Multiple-joint large-muscle group exercises (like squats) should be performed before single-joint, smaller muscle group exercise (like curls). Some other examples of muscle-strengthening exercises include push-ups, pull-ups, sit-ups, arm circles, lifting weights, working with resistance bands, and even climbing stairs, carrying heavy loads, and heavy gardening.

While aerobic exercise has specific time recommendations (at least 75 to 150 minutes a week, depending on intensity), there is no set amount of time recommended for muscle strengthening. The key is to perform each muscle-strengthening exercise until it would be difficult to do another repetition without help. If your goal is to enhance muscle strength, one set of eight to 12 repetitions of each exercise is effective, although two or three sets may be more effective. The ACSM recommends 10 to 15 repetitions for older and frail individuals. The development of muscle strength and endurance is progressive over time. When you can get through the repetitions fairly easily, gradually increase the amount of weight you’re lifting to continue getting stronger.

It’s important not to work the same muscles or muscle groups two days in a row. Intense exercise actually damages muscle fibers, and the body needs time to repair them before you work them again. It is this repair process that causes muscles to grow and become stronger, as cells fuse to muscle fibers to form new muscle protein strands or repair damaged fibers. While a single bout of exercise starts working to build new muscle within two to four hours after the workout, it can take several weeks or months to see a visible difference in your muscles, so stick with it.

Some types of strength training exercise are described in the following sections. (For specific strength training suggestions, see Box 5-7, “Recommended Strength Training Regimens, by Goal”.)

Isometric Exercise

Isometric exercise is a type of strength training in which the length of the muscle doesn’t change and there’s no visible movement at the joint. In other words, you’re tensing the muscle without actually moving. Also known as static strength training, isometric exercises include things like holding yourself in a seated position with your back against a wall (wall squat) or holding a light weight straight out to the side parallel to the ground until your arm begins to drop (isometric shoulder raise). Exercises like these are often used for rehabilitation because they strengthen muscles without placing stress on joints, but they can be used for general strength conditioning as well. While they aren’t the best choice if you want to strengthen your muscles for dynamic activities like sprinting and jumping, isometric exercises can be useful in training for activities that require static strength, like climbing, mountain biking, skiing, Judo, and horseback riding.

As with any exercise, it’s important to warm up first. It’s also recommended that you engage your core regardless of which muscle you’re working. This will help you maintain correct posture, and it has the added bonus of strengthening your core muscles.

While resistance training (like weight lifting) is measured by the number times a movement is repeated (repetitions) and how many sets of repetitions you do, isometric exercises are measured by number of repetitions and length of time the action is held (duration). Research shows that both longer duration (10 seconds or more) with fewer repetitions and shorter duration (two or three seconds) with more repetitions seem to increase static strength. In general, if you would like to add isometric exercises to your strength training routine, try 15 to 20 actions held for three to five seconds each, three times a week.

While isometric exercise are low-impact and therefore may seem low-risk, there are some cautions that come along with an isometric training program. People with cardiovascular disease or high blood pressure should consult a doctor before starting isometric exercises, because your blood pressure can rise while you’re holding these static positions. It’s especially important to remember to breathe while you’re holding a pose, since holding your breath raises blood pressure.

That being said, and an isometric exercise routine may actually help to lower your blood pressure (see Box 5-8, “Home-Based Isometric Exercises Reduce Blood Pressure”).

Core Fitness Routine

Core strengthening is one form of resistance exercise. As introduced in Chapter 2, your core includes the muscles of the abdomen, lower back, and hips. Building a strong core provides a good foundation for all physical activity. Core muscles are essential to movement and provide strength, flexibility, and balance—impacting your ability to do all kinds of daily activities. A strong core also helps prevent falls and injuries during everyday activities.

One popular core training method is Pilates (pi-LAH-tees) exercises. Based on the teachings of Joseph Pilates in the late 1920s, this non-impact exercise program is designed to strengthen your core muscles while simultaneously developing flexibility, balance, control, and inner awareness. It became popular with dancers and other athletes.

In Pilates, the quality with which each exercise is performed is more important than the number of repetitions. The twisting, stretching, pushing, pulling, and rolling exercises are typically performed on the floor, but can involve other equipment. Fundamental exercises include pelvic tilts, bridges, hip rolls, and “cat” stretches, where you get on all fours and arch your back.

Core-Training Tips

- Warm up prior to core training with some light aerobic exercise, such as walking and jumping jacks.

- Use an exercise mat, towel, or blanket during core exercise for extra cushioning.

- Before you start a core-exercise move, engage (tighten) your core by imagining you are tightening a corset around your waistline or preparing for someone to punch you in the abdomen.

- Do core exercises carefully, being sure to maintain correct form. If your form starts to fall apart, back off the length of time you’re holding a position and/or the number of reps. Once you can do a full set well (typically eight to 10 reps), work up to doing another set, for a maximum of three sets.

- Stop core exercise if a movement is painful. Check that you’re doing the exercise correctly. If you believe you’re doing it correctly yet it still triggers pain, check with your doctor, physical therapist, or other trained professional.

- Don’t expect results overnight. Learning to engage your core muscles during exercise, as well as automatically during daily activities, takes time. Do core exercises two or three times a week.

- Complement core training with a regular aerobic exercise program, such as fitness walking.

The post 5. Exercise Routines appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 5. Exercise Routines »

Powered by WPeMatico