3. Shape Up Your Plate

The dramatic impact of nutrition on health (as discussed in Chapter 1) is indisputable. Being mindful of what you eat is important at all ages but becomes even more important as you get older. As you age, the number of calories you need tends to decline, but vitamin and mineral needs don’t. In fact, since absorption of nutrients in the digestive tract becomes less efficient, requirements for certain nutrients actually increase as you age. In order to meet your nutritional needs but remain within your calorie limit, you should focus on eating the most nutrient-rich foods you can.

The choices you make day in and day out comprise your dietary pattern, and studies show that these patterns can have a significant impact on health. While changing behaviors in regard to food habits can be difficult, even small changes in the right direction can make a difference.

Ideal Eating Patterns

The ideal diet is one that provides all of the nutrients and compounds you need to live, fight disease, and be active, in the proportions you need to maintain a healthy weight. The latest recommendations and tools can make it easier for you to make the behavior changes necessary to move toward an ideal eating pattern.

Dietary Guidelines for Americans

Every five years, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) jointly publish a report with nutritional and dietary information and guidelines. This report, called “Dietary Guidelines for Americans,” is required by law to be based on the latest scientific and medical knowledge. While previous editions focused primarily on individual dietary components, such as food groups and nutrients, the 2015-2020 “Dietary Guidelines for Americans,” focuses on eating patterns. This change is in response to the emerging understanding that the components of foods interact with each other and can have cumulative effects on health. It also recognizes that people eat foods, not nutrients.

Rather than excluding foods or food groups, demanding you count grams or calories, or relying on supplements, dietary patterns ensure you get everything you need so your body functions at its best. A healthy eating pattern is flexible and can be adapted to people’s personal, cultural, and traditional preferences. And it fits within their budget. According to the Guidelines, a healthy eating pattern includes:

- A variety of vegetables from all of the subgroups: dark green, red and orange, legumes (beans, peas, lentils, and peanuts), starchy, and other

- Fruits, especially whole fruits

- Grains, at least half of which are whole grains

- Fat-free or low-fat dairy, including milk, yogurt, cheese, and/or fortified soy beverages

- A variety of protein foods, including seafood, lean meats and poultry, eggs, legumes, and nuts, seeds, and soy products (see Box 3-1, “Soy Safety”)

- Oils

A healthy eating pattern limits:

- Saturated fats (less than 10% of calories per day)

- Trans fats

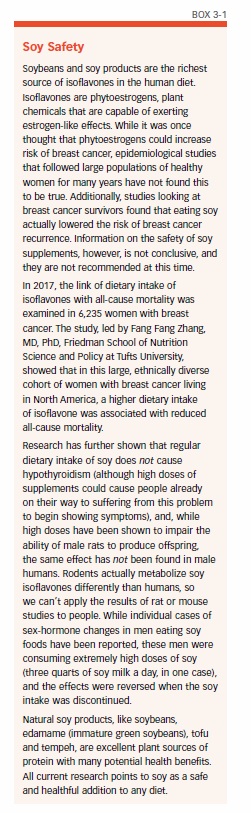

- Added sugars (should make up less than 10% of calories per day) see Box 3-2, “Recommended Intake of Added Sugars”

- Sodium (less than 2,300 milligrams per day)

- If alcohol is consumed it should be consumed in moderation—up to one drink per day for women and up to two drinks per day for men of legal drinking age

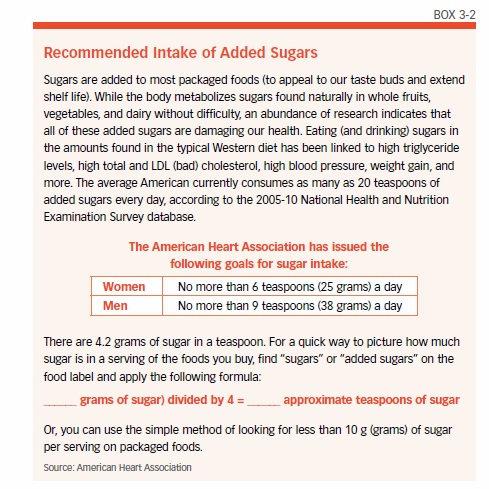

Tufts’ MyPlate for Older Adults

The Dietary Guidelines suggest the best food choices to make for your health, but they aren’t so intuitive when it comes to figuring out how much to eat and in what proportions.

Tufts’ MyPlate for Older Adults, updated to meet the latest dietary guidelines in 2016 with support from the AARP Foundation, is a plan that provides a simple guide to help you choose what to eat and how much of it to eat. It encourages you to choose several different categories of foods at every meal, which can help you take in a broader variety of vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients. A graphic of the Tufts’ MyPlate shows you how to proportion your daily foods, (see box 3-3).

- Vegetables and fruits should make up half of what you eat at every meal. These powerhouse foods are rich in vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and other beneficial plant components that support health and activity. Choosing an assortment of colorful produce, such as dark green, red, and orange, helps you get a wider array of nutrients. Frozen and canned produce are often just as nutritious as fresh (and sometimes more so), and they’re convenient, easy to prepare, and can help stretch your budget. Opt for plain frozen vegetables, low-sodium canned produce, and fruit packed in water or its own juices to avoid added fat, sugar, and salt.

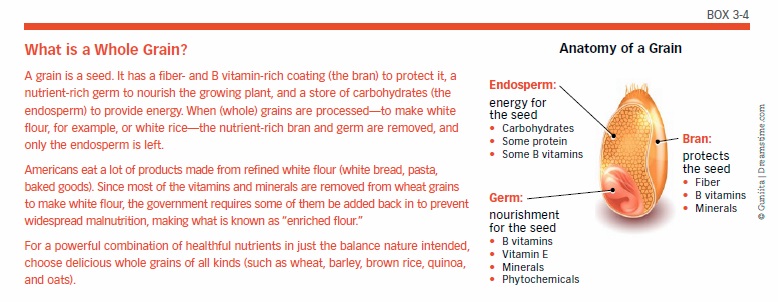

- Whole grains should make up one-fourth of your plate. These foods—such as whole wheat bread, brown rice, barley, rye crackers, and oatmeal—supply complex carbohydrates to help fuel your muscles, B vitamins to support metabolism, and fiber to help keep your digestive tract running smoothly. Smaller amounts of fortified refined grains, such as unsweetened fortified breakfast cereal, also can be included (see Box 3-4, “What is a Whole Grain?”).

- Protein-rich foods should make up the final one-fourth of your plate and include foods such as fish, chicken, turkey, eggs, lean red meat, legumes, natural (unsweetened) nut butter, tofu, and dairy products, such as low-fat Greek yogurt and reduced-fat cheese.

- Plant-based oils, such as soybean, corn, canola and olive oil, and soft spreads, are shown in the center of the graphic and can be used in small amounts. They provide essential fatty acids (needed in small amounts) and some fat-soluble vitamins.

- Hydrating beverages are pictured above the plate to remind you to include these throughout the day. Top choices are water, tea, and low-fat (one percent) milk. You can include small amounts of coffee and 100-percent fruit juice, if desired. Soup also makes a substantial contribution to your fluid intake.

- Physical activity icons appear below the plate graphic because being active also is essential for good health and can help improve quality of life.

Plant-Based Diets

Research clearly associates a diet high in plant foods (like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and beans) and low in meats with better health (see Box 3-5, “The BROAD Study: Plant-Based Diets Improve Health”). The Meatless Monday campaign, in association with the Johns Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health (meatlessmonday.com), reports that going meatless even one day a week will not only reduce cancer and heart disease risk, fight diabetes, curb obesity, and increase life span, it will also support the environment by reducing carbon footprint and water usage and by decreasing dependence on fossil fuels.

Whether you’re a vegetarian (avoiding meat, but still eating eggs and dairy), a vegan (eschewing all animal products), or a pescetarian (including fish and seafood in an otherwise vegetarian or vegan diet), it’s entirely possible to fuel your body for good health, with plenty of energy for exercise left over.

Getting adequate protein is key when choosing a plant-based diet. While dairy and eggs are the most obvious sources of protein in the vegetarian diet, plants contain protein as well. The soybean has long been a remarkably versatile protein source in Asian cultures. Steamed right out of the pod (edamame), roasted (soy nuts), coagulated (tofu), fermented (tempeh), as paste (miso), porridge, nut butter, or “milk,” soy is an excellent source of protein.

Other legumes (beans, lentils, peas, and peanuts) provide protein as well, and world cooking abounds with examples of nutritious meals built around them, such as rice and beans or couscous with chickpeas. Nuts and nut butters are a tasty way to add protein to meals, and they also provide “good” monounsaturated fat.

Grains contain protein as well. The tasty and adaptable grain quinoa (KEEN-wah) is an excellent protein source. While it was once believed that plant-based meals had to be eaten in combinations that produced “complete proteins” (containing all nine of the essential amino acids), it is now understood that eating a variety of fruits, vegetables, grains, beans, nuts, and seeds over time can provide all of the amino acids the human body needs. (See Chapter 4.)

Iron from plant foods is not as well absorbed as iron from animal foods like meat, poultry, and fish, so vegetarians and vegans are at greater risk of iron deficiency. Common plant sources of iron include fortified breakfast cereals, legumes, spinach, tofu, and raisins. Vitamin C helps boost absorption of iron from plant foods, so try slicing vitamin-C-rich strawberries onto cereal or tossing orange slices into a black bean salad.

Another concern for vegetarians, and especially vegans, is the potential for vitamin B12 deficiency, since B12 is found only in animal products. Fortified cereals and nutritional yeast can help, but you should have a doctor periodically check your B12 levels to see if you need a supplement.

Today’s market abounds with a wide variety of meat substitutes. Vegetarian burgers, hot dogs and sausage, faux chicken patties and nuggets, crumbles for tacos and Bolognese sauces, and even meaty “steak tips” are readily available in the refrigerated or frozen sections of mainstream and specialty stores. Many of these products are soy-based, but others employ grains, beans, vegetables, or mushrooms to good effect.

While these pre-packaged options can be helpful additions to a vegetarian diet, it’s important to watch these items for high calories and high sodium. Fresh-prepared meat-free meals can be just as simple and more satisfying. If you’re just getting started, adapting some traditional favorites can ease the transition. Vegetarian chili is delicious and nutritious with beans, but adding bulgur or other grains can provide a meaty chew. Top with shredded cheese, sour cream, and sliced green onions or cilantro, and serve with sides of rice and cornbread for a crowd-pleasing meal. Tacos or Sloppy Joes can be made with pre-packaged meatless crumbles, but lentils work nicely as well. Portobello mushrooms are known for their meaty flavor and texture and work well whole as a burger replacement or chopped in pasta sauce. For those avoiding dairy, there are now cheese substitutes that actually melt, and, with some experimentation, milk substitutes can work in baking as well as breakfast cereal.

Many non-Western diets rely less heavily on meats and offer an amazing array of fabulous flavors just waiting to be explored. Chinese vegetable stir-fries and tofu dishes may be familiar to many, but the fresh tastes of Vietnamese cooking, the rich coconut milk curries of Thai, the lentil dal in Indian food, bean dishes in Mexican cooking, and the chickpea-based hummus and falafel from the Mediterranean region are just a few examples of vegetarian options to explore. Pick a vegetarian cookbook that appeals to you, or use the many free vegetarian websites or the vegetarian sections of popular recipe resources on the Internet.

Timing of Meals

Research hasn’t clearly shown that eating three meals a day is any better or worse than five or six smaller meals, but we do know you should avoid eating less than three times a day, as that could make it tougher to control your appetite. How often and at what times you should eat, therefore, come down to personal preference and your work or activity schedule. Just remember that the more often you eat, the less you should eat at a time.

If you’re eating three meals a day and find that you’re often overly hungry at the evening meal, add a mid-afternoon snack to help keep hunger in check. Depending on what time you eat breakfast and lunch, you may or may not need a morning snack.

Although many people do report eating an evening snack, check in with yourself first to determine if you’re truly hungry or just eating mindlessly, perhaps triggered by food commercials on television or the habits of others in your household. On the other hand, if you won’t be able to eat much prior to an early-morning athletic event, eating a nutritious bedtime snack the night before can be a smart move.

Eating for Weight Loss

While it’s easy to get the impression that there are special weight-loss foods, taking off pounds is actually all about using up more energy than you take in, regardless of what foods you eat. Any diet that cuts calories should result in weight loss, assuming you maintain the same level of exercise, but following a healthful dietary pattern like the ones outlined in this chapter will make it more likely that weight loss is accompanied by good health, and it could make weight loss easier and more pleasant as well.

Satisfying Choices

Eating less and moving more is the best way to achieve a “calorie deficit,” a state where you burn more calories than you take in. The key to eating less is to make the foods you eat fill you up (satiation) and keep you satisfied longer (satiety).

Over the years, carbohydrate, protein, and fat have all been suggested as the food component in control of making us feel satisfied and stay satisfied. While there is research to support each one, protein has risen to the top as the most satisfying nutrient, followed by carbohydrate, and then fat.

But these macronutrients are not alone in controlling our hungry/full signals. Micronutrients like calcium also play a role in control of appetite. This may be because the body is designed to make sure it gets what it needs. When you’re running low on an important nutrient like calcium, your body sends out a signal that you’re hungry in order to try to get more of what it needs.

Even non-nutrient food components get in on the act. Fiber, for example, will help you feel full longer—even if you take in fewer calories. So choosing naturally high-fiber foods like whole grains, vegetables, and fruits alongside your protein may allow you to eat more satisfying meals, while still cutting calories.

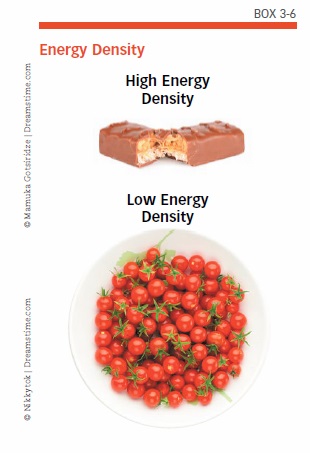

Energy Density

One key to staying satisfied and well-nourished while watching caloric intake is to consider the energy density of your food. Energy density is the calories per gram of food. Foods with high energy density provide more calories per bite than foods with low energy density. Choosing low energy density foods allows you to take in fewer calories while eating the same amount of food in a day (or maybe even more).

Low energy density choices include fruits, vegetables, beans, and whole grains, foods with a lot of liquid like soups and stews, and low-fat foods like pasta, breakfast cereals, and yogurt.

Some examples of foods with medium/high energy density include salmon, lower fat cheese, and lean red meat. Some foods with medium energy density, such as pizza, pastries, cakes, and jams, are higher in fat or sugars and should only be consumed occasionally and in small amounts.

If you’re trying to lose weight, limit foods with an energy density of more than four calories per gram, like cookies, chips, peanuts, cheese, butter, oil, and mayonnaise. These foods tend to be high in fat and have a low water content.

A great way to make meals more filling and satisfying without adding extra calories is to add vegetables. Toss an extra helping of your favorites into stir fries, stews, chili, pasta dishes, and salads. Pulses (beans, peas, and lentils), which provide both protein and fiber without a lot of calories, are a great addition to any meal. Dietary staples in many cultures, pulses work well in chili, soup, or salad, or stirred into rice or pasta dishes to make them more nutritious and filling.

The low energy density and high fiber content of fruits and vegetables have both been linked to improved weight control, but it’s possible that some may be more powerful than others. In 2016 the British Medical Journal reported an association between eating more flavonoid-rich fruits and vegetables and less weight gain. Flavonoids, including anthocyanins, are phytochemicals found in foods like berries, apples, pears, grapes, celery, and peppers (see photo box 3-6 “Energy Density”).

Other Factors

Multiple studies have linked eating quickly to being overweight. Slower eating tends to result in eating less. Staying hydrated and getting enough sleep are also important when you’re trying to control your appetite. Making sure you don’t skip meals (like breakfast) and don’t eat too late at night may help as well.

So, even if there are no magic weight-loss foods, there are clear ways of eating that will make weight loss easier, while ensuring you stay well-nourished and satisfied. Based on research on satiety and energy density, the keys to eating for weight loss are:

- Eat some lean protein with every meal and snack

- Choose high fiber carbohydrates like whole grains

- Bulk up meals with more vegetables and legumes to cut calories without sacrificing volume

- Limit high fat foods.

Combine these tips with proportions like those in the Tufts’ MyPlate and regular physical activity for healthy weight-loss success.

Trendy Diets

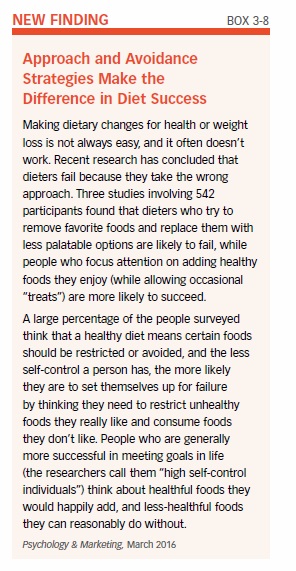

It seems like there is always some new food or diet plan that promises to make you healthy or thin (see Box 3-7, “What are Superfoods?”). There are many diet patterns to choose from that can help you meet your health goals, so make sure you choose a healthful option you can follow long-term (see Box 3-8 “Approach and Avoidance Strategies Make the Difference in Diet Success”). Some of the more recent dietary plans capturing interest include the gluten-free diet, Paleolithic diet, and intermittent fasting.

Gluten-Free Diet

With the explosion of gluten-free foods on supermarket shelves, often housed in the “health” section of stores, it’s understandable that many people conclude that a gluten-free diet is somehow more healthful. This diet, which omits all gluten-containing grains (wheat, barley, and rye), is essential to people with celiac disease, a genetically-based disorder that affects 1 to 1.5 percent of the population. Additionally, 5 to 10 percent of the population with medically-diagnosed non-celiac sensitivity also find relief from symptoms, such as diarrhea and abdominal bloating, with a gluten-free diet. There is not a valid blood test available to help diagnose non-celiac gluten sensitivity. A doctor may diagnose it after tests for celiac disease and wheat allergy are negative, and finding that a gluten-free diet resolves certain symptoms and the symptoms return when a person consumes gluten.

Cutting out gluten simply as a way to eat healthier, lose weight, or in an effort to improve athletic performance has not been shown to be beneficial. Gluten-free packaged foods are still processed foods and not necessarily any better for you. In fact, refined gluten-free flours are not required to be enriched like refined wheat flour is, meaning none of the nutrients stripped out in processing need to be added back in. Packaged gluten-free sweets may contain just as much refined flour (such as white-rice flour), sugar, and fat as their gluten-containing counterparts.

Without expert dietary guidance, following a gluten-free eating plan could put you at increased risk of nutritional deficiency, and may reduce beneficial gut bacteria. Although some people do lose weight (at least temporarily) when following a gluten-free diet, it’s often because they have eliminated a lot of highly refined packaged and fast foods, such as white bread, pizza, and pastries, that are easy to over-consume.

Paleolithic Diet

The Paleolithic (“Paleo”) diet aims to emulate the dietary patterns of our Stone Age ancestors. It focuses on avoiding processed foods and emphasizes intake of vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds, eggs, poultry, fish, and lean meat, particularly grass-fed meat. These dietary principles may not sound too radical, but in the diet’s purest form, dairy products, grains, and legumes are excluded entirely, which could increase risk of falling short on some nutrients.

With careful planning, a person may be OK following a Paleo dietary pattern, and scientific studies suggest it may hold merit in reducing risk of certain diseases, such as colon cancer and cardiovascular disease, as well as improving control of chronic health concerns, such as type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. However, such evidence is preliminary. Further study is needed. The low-calorie nature of this diet doesn’t strongly support a robust physical activity regimen. It’s possible that people could experience similar health benefits by simply cleaning up their eating pattern to emphasize whole, minimally processed foods, rather than adopting the extreme principles of a Paleo eating plan.

As with any trendy diet, there is concern that someone will attempt to follow the diet without fully understanding its principles, which could lead to poor choices, such as eating a lot of hot dogs, bacon, and sausage. These are processed meats linked with increased cancer risk and not something a Paleo diet would include. Over the long term, a Paleo dietary pattern also could be difficult to stick with, and some experts view it as unsustainable from an environmental standpoint.

Intermittent Fasting

Intermittent fasting is promoted to athletes as a way to speed up fat loss and muscle growth. Rather than addressing what you eat, intermittent fasting focuses on when you eat (and don’t eat). There are many variations on how to do it, such as a complete fast every other day; fasting daily for 16 hours, such as from 9 p.m. at night to 1 p.m. in the afternoon the next day; or eating only 25 percent of your energy needs on two (non-consecutive) days a week while eating as desired the other days.

Doing aerobic exercise while fasting could increase loss of lean muscle mass since muscle protein will be burned for fuel. Having readily available energy to draw upon during exercise tends to lead to greater calorie-burn overall. Exercising in the fasting state also can decrease balance and increase risk of injury. Lastly, intermittent fasting is not recommended for people with diabetes or who need to closely regulate their blood sugar, and it has not been studied in adults of advanced age.

The post 3. Shape Up Your Plate appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 3. Shape Up Your Plate »

Powered by WPeMatico