2. Shape Up Your Body

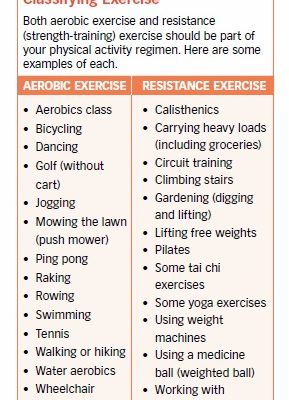

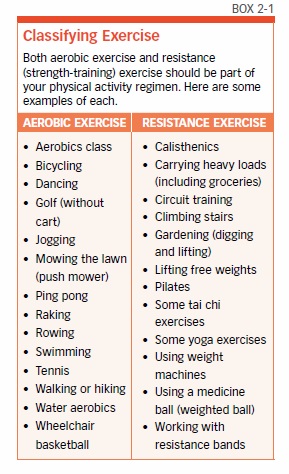

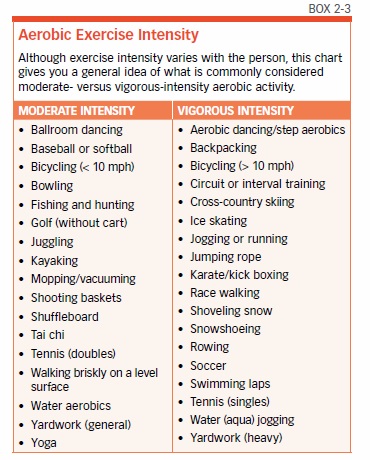

There are lots of good reasons to move more and sit less. The best type of exercise varies from person to person, based on your individual goals and abilities. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issues physical activity guidelines based on the latest scientific information. The most recent recommendations (the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans) described in this chapter, recommend both aerobic exercise and resistance training for all adults. For examples of aerobic versus resistance exercise, see Box 2-1, “Classifying Exercise.” Both aerobic and resistance exercise provide several important benefits, many of which overlap, but in certain cases, the different forms of exercise have unique benefits (see Box 2-2, “Effects of Aerobic Exercise and Strength Training”).

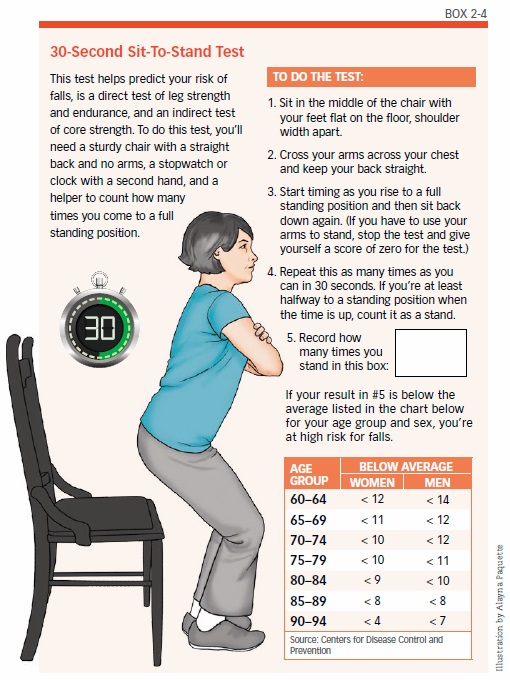

The Physical Activity Guidelines also recommend balance training for older adults at risk for falls. While the exercises in this report aren’t designed specifically for balance training, regular physical activity can help reduce risk of falls, since balance can be impacted by muscular strength and aerobic endurance. A large review of adults 45 and over found that those who reported doing regular physical activity (such as running, calisthenics, golf, gardening, or walking for exercise) were significantly less likely to report one or more falls in the previous three months.

If you’re not able to do a lot right now, do whatever amount of activity you can—even if that’s just 10 minutes a day. There can be significant benefits in progressing from no physical activity to a little activity. Whether you’re just getting started or looking to step up your exercise plan, slowly increase the amount of time you exercise then gradually increase the intensity. No matter what your current fitness level, moving more and sitting less can help you stay healthy and active as you age.

Physical-Activity Recommendations

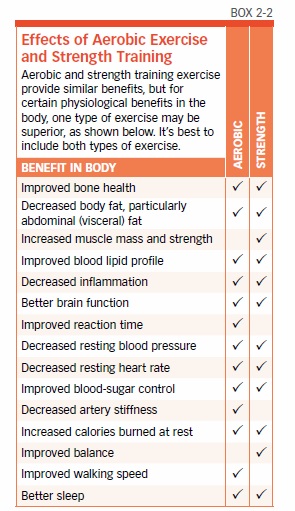

It’s recommended that all adults get at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity exercise or at least 75 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, plus muscle-strengthening exercises that work each major muscle group (arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen, back, hips, and legs), at least twice a week. For examples of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic exercises, see Box 2-3, “Aerobic Exercise Intensity.” For examples of aerobic and muscle-strengthening exercises, see Box 2-1, “Classifying Exercise.”

Aerobic Recommendations

Aerobic activity, sometimes called endurance exercise, involves moving large muscle groups in a rhythmic manner for an extended time period, such as 10 minutes or more. Common examples are brisk walking, dancing, swimming, jogging, and biking. Aerobic exercise enhances the performance of your heart, circulatory system, and lungs. Here is what the latest guidelines say about meeting the requirement of 150 minutes (2½ hours) of moderate or 75 minutes (1¼ hours) of vigorous aerobic activity a week:

- For moderate-level aerobic activities, you can break the sessions into three, at 10 minutes each, to total 30 minutes a day. Work toward a goal of at least five days a week.

- For vigorous activity, you can break aerobic exercise sessions into 20 minutes a day, repeated four times a week.

- You can opt to do a combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity exercise, if you wish. In general, two minutes of moderate-intensity activity counts the same as one minute of vigorous-intensity activity. For example, 15 minutes of vigorous walking (such as walking up hills) counts as 30 minutes of moderate-intensity walking. With vigorous exercise, you get similar health benefits in half the time it takes you with moderate exercise.

- If you’re already active, you can gain even more health benefits by moving beyond the 150 minutes and aim for 300 or more minutes a week of relatively moderate-intensity aerobic activity.

Strength-Training Recommendations

Strength training, also known as resistance training, is a form of physical activity that exercises a muscle or muscle group against external resistance. It can be performed using free weights, weight machines, resistance bands, or stability balls, or using your own body weight to supply the resistance.

Resistance exercise comes with its own terminology. A repetition, or “rep,” is the number of times you perform a complete movement of a given exercise, such as a bicep curl. A set is a group of reps. If you do two sets of 10 bicep curls (10 reps) in an exercise session, it would total 20 bicep curls. (The American College of Sports Medicine recommends that older and frail adults choose a level of weight that allows them to do 10 to 15 repetitions per set.)

To meet your goal of increasing muscle strength, resistance training should be progressive. You should gradually increase the resistance or level of difficulty and number of sets up to a maximum of three sets per exercise. For example, you might start with two sets of bicep curls with 12 reps using five-pound weights, then progress to three sets of eight to 10 reps using five-pound weights, gradually working up to 15 reps per set. Once you’re able to do 15 reps per set of bicep curls with five-pound weights, you can increase the weights to eight pounds and gradually increase the number of reps and sets in the same fashion as you did with the five-pound weights. When you progressively overload muscles in this way, you’ll get increases in strength and perhaps mass.

- There is no set length for strength-training exercise sessions, but the goal is to do eight to 12 repetitions of each exercise and, if you’re able, you can do two or three sets (of eight to 12 repetitions) of each exercise.

- You can do eight to 10 different resistance exercises in a session, two to three days per week.

- You rest two to three minutes between sets and between different exercises to keep your muscles from becoming overly tired.

- Avoid lengthy sessions (longer than 45 minutes) because you’ll become more fatigued and increase your risk of injury. Generally, 20- to 45-minute resistance training sessions are recommended for older adults.

- Do not exercise the same muscle groups on two consecutive days. After resistance exercise, muscles need recovery time, as your body starts to repair and replace damaged muscle fibers, forming new strands of muscle protein that result in stronger muscle tissue and, in some cases (particularly in younger individuals and men), bigger muscles.

- As you become more advanced, you may prefer to split up your muscle-training routine, which means you might exercise specific muscle groups one or two days a week and the remaining muscle groups on a separate one or two days. This is fine, as long you allow at least 48 hours of recovery time for each muscle group.

Core Training

Core training exercise, which targets the muscles attached to your trunk and spine, should be done in addition to traditional resistance training exercise. Core muscles are involved just about every time you move your body and thus support other physical activity. Although there are varying definitions of the “core,” it generally refers to the muscles in your abdomen, lower back, and hips. These muscles help you stand, bend, twist, reach, stoop, and turn. When these muscles are strong, they help you stand up straight (rather than hunching over), and they promote good balance, helping prevent falls. A strong core also helps reduce the likelihood of injuring your lower back.

When core muscles are weak, not only is physical activity more difficult, but eventually daily activities, such as getting dressed, carrying groceries, or vacuuming, can become a challenge. Signs of a weak core include poor posture (whether you’re sitting or standing), lower back pain, and muscle weakness in your arms and legs. Clues you may have poor posture include a head that’s commonly thrust forward, slouching, rounded shoulders, and excessive arching of your lower back with your stomach or abdomen protruding. An indirect test of core-strength is the sit-to-stand chair test (see Box 2-4, “30-Second Sit-to-Stand Test”). For core training ideas, see Chapter 5.

Preventing Injury

Warming up and cooling down (see “Warming Up, Cooling Down,” Chapter 5) can help prevent injury, but the most important tip is to not overdo it. Increase your level of physical activity slowly, and choose workouts that are appropriate for any health conditions you may have (see Chapter 9 for more information on exercising with common chronic conditions). If you have pains, tightness, or pressure in your chest during normal activity, if you currently experience dizziness or lightheadedness, if you have high blood pressure or pain, stiffness or swelling that limits activity, or if you feel unsteady or are prone to falls, talk to your doctor before you begin any new exercise activities. “No pain, no gain” has been proven wrong. If an activity hurts, stop doing it right away.

Choosing the right workout for your needs or physical limitations and learning the proper technique for performing each exercise can keep you from hurting yourself. Getting the right gear (see “What to Wear” in Chapter 8), staying hydrated (see Chapter 6) and varying your workouts so you aren’t stressing the same muscle groups every time are important as well.

Most older adults can increase their physical activity at least to a moderate degree. If you’ve been inactive for a while, start at a low level of activity and work your way up slowly over time. Some older adults avoid exercise and physical activity due to fear of injury. In reality, the risks of being sedentary are far greater than any small risks that might come with starting light-to-moderate activity. The main risk is that your muscles may be sore in the first few weeks of starting an exercise program. Although you likely won’t be able to avoid this completely, and it’s important to challenge yourself, one of the best ways to reduce muscle soreness is to gradually progress in your exercise program rather than trying to do too much at the start. Muscle soreness generally resolves by itself within a few days.

Exercise and Weight Management

For some people, one motivation to exercise is to help achieve and maintain a healthy body weight. Sedentary adults typically gain 17 to 20 pounds of weight (mostly fat) between 18 to 55 years of age, followed by additional gains of two to 4½ pounds over the next decade, with declining body weight thereafter. While some older studies indicate that physical activity does not help with weight loss, the latest research and real-world experience say exercise is a key part of losing weight and keeping it off (see Box 2-5, “Physical Activity Does Help with Weight Loss”).

Healthy Weight Targets

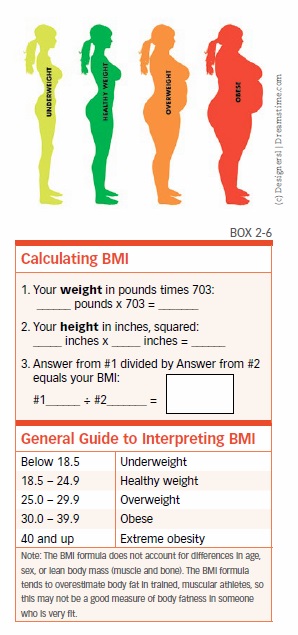

The most commonly used gauge of a healthy body weight is body mass index (BMI), which is an indirect way of estimating how much body fat you have. If you know your height and weight, you can calculate your own BMI. If you have Internet access, you can let a website do the math for you, such as the calculator at calculator.net/bmi-calculator.html (see Box 2-6 for how to calculate and interpret BMI).

With aging, women lose both lean body mass and height, so some experts have questioned whether BMI is an accurate predictor of obesity in aging. However, a recent study of women up to 95 years of age found that, despite changes in height and lean body mass, BMI was still a good predictor of body fat in older women. While some studies have suggested that a higher BMI in later years correlates with a lower risk of death, the latest information strongly disputes that assertion (see Box 2-7, It Turns Out Being Overweight Does Not Extend Your Life”).

Falling at the extreme ends of the BMI range—including extreme obesity and underweight—seems to pose the greatest risks for mortality. Your doctor can help you determine if weight loss would benefit you and can monitor you appropriately. If you’re taking medications, for high blood pressure or type 2 diabetes for example, they may need adjusting as you lose weight. Exercise and optimal nutrition will be needed to lose weight safely and to minimize loss of muscle and bone.

The issue of obesity in older adults is a relatively new phenomenon. Anyone who becomes obese in middle-age and remains obese in older age should discuss the best course of action with their physician, as exercise, optimal nutrition, and medical supervision are needed for an older adult to lose weight safely.

Calorie Burn of Activity

Did you know that about 70 percent of the calories you burn a day are a result of activities that are out of your control? How many calories you burn is largely determined by how much energy your body requires to perform basic functions of life, such as breathing, conducting nerve signals, and circulating blood throughout your body, which is called resting energy expenditure or resting metabolism. You also burn calories digesting and processing the food you eat.

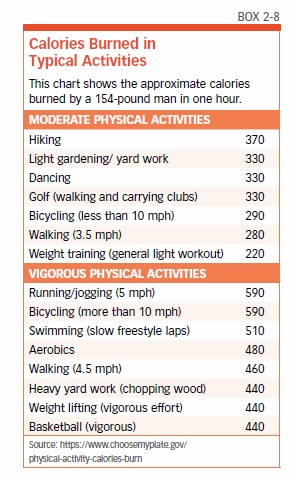

Resting metabolism is impacted by several factors, such as your age, sex, genetics, hormonal changes, body size, and body composition—especially how much skeletal muscle tissue you have. The part of your metabolism you do have control over is how physically active you are. This includes daily activities like doing the dishes, walking to the store, and cleaning the house, as well as structured exercise (see Box 2-8, “Calories Burned in Typical Activities”).

How Exercise Contributes to Weight Loss

Increasing activity increases calories burned, but it may not lead to lower numbers on the scale unless you also change the way you eat. Nevertheless, exercise is important when you’re trying to lose weight for several reasons: When you lose weight, you lose muscle along with fat. A program of regular physical activity that includes resistance exercise can help reduce muscle loss. Additionally, for every pound of muscle you have, you burn approximately six calories a day, while each pound of fat burns only two calories a day, so having more muscle makes it easier to manage your weight.

If you’ve ever thought how much easier it would be to control your weight if you could just control your hunger, regular exercise is key. Aerobic training improves the body’s sensitivity to insulin. That means it takes less insulin to put glucose (derived from carbohydrates you’ve eaten) into your muscles for storage, and ultimately, less of that glucose will be stored as body fat. What’s more, smaller surges in insulin levels after eating means smaller fluctuations in blood sugar, which helps avoid spikes in hunger.

Several studies suggest that making exercise more fun will actually help you eat less. Women asked to take a one-mile morning exercise walk ate 35% more pudding after lunch than those who were asked to test the sound quality of an MP3 music player during the walk.

Similarly, when men and women were instructed to take a mid-afternoon walk, those who were told it was an “exercise walk” later served themselves 206 more calories of M&Ms provided as a snack than those who were told it was a “sightseeing walk.”

Lastly, when runners were offered a chocolate bar (indulgent choice) or a cereal bar (healthier choice) after a competitive relay marathon event, those who reported having more fun during the event were more likely to choose the cereal bar. So do whatever you can to make exercise fun, such as listening to music during a walk or watching a favorite TV show while using the elliptical machine.

The first step in building your exercise regimen for weight control is to aim for 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week. To reach your weight goal, you may need to increase your activity beyond that in conjunction with moderately decreasing the amount of calories you take in (by about 250 to 500 calories a day). By itself, physical activity has a modest effect on weight loss, especially if you’re doing less than 150 minutes of exercise a week; thus, reducing the amount of calories you take in also is important for those who have a lot of weight to lose. When it comes to maintaining weight loss and preventing weight regain over the long term, physical activity is crucial.

The post 2. Shape Up Your Body appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 2. Shape Up Your Body »

Powered by WPeMatico