4. Brain Power Foods

Fruit and Vegetable Smarts

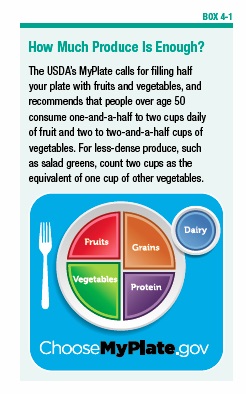

When your mom told you to eat your fruits and vegetables, she may not have known that those foods are good for your brain—but it was good advice in any case. We’ve seen how an overall healthy dietary pattern can help protect against dementia and cognitive decline. It’s no surprise that fruits and vegetables play a dominant role in those brain-healthy patterns, just as they do in healthy diets for your body as a whole (see Box 4-1, “How Much Produce Is Enough?”) But it may be that eating fruits and vegetables helps protect your brain beyond general health benefits.

Fresh Thinking on Fruit

As we saw with the MIND diet in chapter 2, research on the brain benefits of specific foods has focused in particular on berries (see Box 4-2, “More Evidence for Effects of Berries,” on page 41). Pigment compounds called anthocyanins that give berries their distinctive red, purple, and blue colors can cross the blood-brain barrier to become localized in areas of the brain related to learning and memory. Anthocyanins are found in fruits such as blueberries, strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, bilberries, huckleberries, and cranberries, as well as grapes and currants. In the brain, anthocyanins decrease vulnerability to the oxidative stress that occurs with aging, reduce inflammation, and may increase neuronal signaling.

In one large, long-running study of berries’ brain benefits, scientists analyzed data on berry consumption among some 16,000 women over age 70 participating in the Nurses’ Health Study. The women were tested for memory and other cognitive functions every two years and completed dietary questionnaires every four years. Researchers found that those who consumed two or more half-cup servings of strawberries or blueberries per week experienced slower mental decline—equivalent over time to up to two-and-a-half years of delayed aging.

Jump-Start from Berries

In a review of the scientific evidence, Tufts scientists Barbara Shukitt-Hale, PhD, and Marshall G. Miller, PhD, concluded, “A growing body of preclinical and clinical research has identified neurological benefits associated with the consumption of berry fruits. In addition to their now well-known antioxidant effects, dietary supplementation with berry fruits also has direct effects on the brain. Intake of these fruits may help to prevent age-related neurodegeneration and resulting changes in cognitive and motor function.”

Animal studies conducted at Tufts found that the addition of blueberries to the diet improved short-term memory, navigational skills, balance, coordination, and reaction time. Compounds in blueberries seem to jump-start the brain in ways that get aging neurons to communicate again. Moreover, some data in Alzheimer’s patients indicate that blueberries could forestall the brain damage that is a hallmark of the disease.

Another Tufts study found that extracts of blueberries as well as strawberries improved cognitive and memory functions in rats. For two months laboratory rats were fed either a standard diet, or a diet supplement plus blueberry extract equal to that of a daily one-cup portion for humans, or with strawberry extract equal to a daily one-pint bowlful. Half the rats in each group were then exposed to radiation to induce effects similar to cognitive aging. Compared to the rats fed the standard diet, rats that had consumed either blueberry or strawberry extract performed better in tests of learning and memory.

Year-Round Brain Boost

Berries such as blueberries retain their healthy qualities when dried or frozen, and can be enjoyed year round. Consider starting your day with a smoothie that contains a few handfuls of blueberries (using frozen berries reduces the amount of ice you need to add to your blender).

While whole fruits (even pureed in a blender) are a healthier choice than juices, which sacrifice most of the fruits’ fiber content, the anthocyanins in berries and grapes seem to survive juicing. Randomized controlled trials have produced promising evidence for the effects of cranberry, blueberry, and grape juice on cognitive performance in older adults.

One study, for example, tested the effects of Concord grape juice versus a placebo beverage in elderly volunteers who were already suffering mild cognitive impairment. After 16 weeks, those who drank grape juice scored better on tests of memory than those in the placebo group. Measurement of brain activity using functional magnetic resonance imaging revealed greater activation in key parts of the brain among the grape-juice group, suggesting increased blood flow in areas of the brain associated with learning and memory.

Veggies Keep Your Brain Young

Although berry fruits have been studied most thoroughly for brain benefits, eating more vegetables also has been associated with cognitive protection. One study at Rush University found that two servings a day of vegetables prevented the equivalent of five years of mental aging. Participants who ate at least 2.8 servings of vegetables a day over a span of six years slowed their rate of cognitive decline as measured by standardized tests by about 40 percent compared to those who consumed less than one serving a day. Researchers speculated that the high vitamin E content of vegetables might be key to this apparent benefit, noting that vegetables are typically consumed with some fats, which increases the absorption of vitamin E and other fat-soluble antioxidant nutrients.

Another study, involving nearly 2,000 older, dementia-free Japanese-Americans, provides support for the idea that vegetable juice as well as whole vegetables may help fend off Alzheimer’s disease. In the nine-year study, participants who drank at least three glasses of fruit or vegetable juice per week were 76 percent less likely to develop Alzheimer’s compared with those who averaged less than one glass per week. Even those who drank only one or two servings weekly had some protection compared with those who consumed less juice.

Meet the Phytochemicals

The anthocyanins in berries and the compounds called polyphenols found in apple, grape, and citrus fruits and juices (particularly those that have been mechanically squeezed with the peels) are examples of natural plant compounds called phytochemicals (or phytonutrients). Diane L. McKay, PhD, an assistant professor at the Tufts’ Friedman School and a scientist in its Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging Antioxidants Laboratory, explains, “These are not classic nutrients like vitamins. These are compounds present in plants that have biological activity that confers health benefits, such as improving markers of disease risk. All phytochemicals have antioxidant activity, but that is not necessarily their mode of action in the body. They may turn cells on or off, affect inflammation—a whole cascade of events.”

There is growing evidence that fruits and vegetables containing phytochemicals can counteract age-related declines in cognitive functioning. Among the most-studied phytochemicals are the large group of polyphenols, which include catechins (found, for example, in tea) and flavanols (found in chocolate).

“But, there are thousands of phytochemicals to be identified, and we’re still going,” McKay says. That phytochemical variety is another reason to consume a wide mix of plant foods in your diet: “You never really eat just a single phytochemical. They have synergistic effects.”

Nuts for Heart and Head

Evidence continues to mount that consuming nuts can help improve cholesterol levels and protect your heart and arteries, which is also a plus for your brain. Some studies also have looked specifically at possible cognitive benefits from nuts. Adding nuts, as well as olive oil, to a Mediterranean-style dietary pattern was found to make that diet more effective against cognitive impairment (see Box 4-3, “Nuts, Olive Oil Bolster Mediterranean Diet Brain Benefits”).

In a study done at Tufts, the phytochemicals and healthy fats in walnuts seemed to improve brain function in laboratory rats. For eight weeks, the animals were randomly assigned to eat a diet containing zero percent, two percent, six percent, or nine percent walnuts. Then, they were given age-sensitive tests of balance, coordination, and spatial memory. Rats that consumed the two percent and six percent walnut-enriched diets showed improved motor and cognitive function. The six-percent-walnut diet would equate to a human eating one ounce of nuts per day. Intake of larger amounts of walnuts did not provide additional benefits.

Nutritional Powerhouses

What makes nuts so good for you? Like other plant foods, nuts—including not only tree nuts but also peanuts (technically legumes)—are rich sources of phytochemicals. These little nutritional powerhouses are also excellent sources of vitamin E and magnesium. Individuals consuming nuts have higher intakes of folate, beta-carotene, vitamin K, lutein plus zeaxanthin, phosphorus, copper, selenium, potassium, and zinc than those who do not consume nuts.

Though nuts vary in their mix of vitamins, minerals, and heart-healthy fats, the type of nut you choose to consume probably doesn’t matter much. You might do best by simply eating a variety of nuts, consumed as a substitute for less-healthy snacks.

Good News for Chocolate Lovers

People have been consuming chocolate, mostly in the form of cocoa beverages, for some 3,500 years, and today science is finding that the ancient Olmec, Mayan, and Aztec peoples were on to something when they first developed a chocolate beverage from cocoa beans. Phytochemical compounds called flavanols found in dark chocolate (the darker, the better) and cocoa have been shown to have cardiovascular benefits. But in news that cheered chocoholics everywhere, those same compounds also may be good for your brain (see Box 4-4, “Chocolate Lovers Score Higher on Mental Tests”).

A study published in 2015 reported that the flavanol compounds found in cocoa and dark chocolate might have benefits for specific mental functions, even in the short term. An eight-week study of 90 cognitively healthy older volunteers randomly assigned to three different levels of flavanols found improvements in verbal fluency and tests of visual attention and task switching, with greater benefits associated with higher amounts. Both the high- and intermediate-flavanol beverages were associated with significantly greater improvements in scores, compared to the low-flavanol drink.

Another study reported that a chocolate drink high in flavanols enabled participants to complete memory-related tasks with less effort. The randomized trial compared three strengths of flavanol-laden beverages on 63 volunteers, ages 40 to 65, over a 30-day period. No difference was seen in tests of mental accuracy and reaction time. But, while performing the memory-related tasks, during which their brain activity was monitored with CT scans, participants in the middle and top groups of flavanol supplementation required less brain activity to accomplish the tasks than those in the lowest group.

Chocolate also may improve insulin resistance, according to a recent study of people in Luxembourg, which could in turn help protect the heart and brain.

Chocolate Versus Impairment

Some findings suggest that cocoa may have greater benefits for people who have already suffered cognitive impairments than those who are cognitively healthy, although others report preventive benefits. In one Italian clinical trial, for example, older adults with mild cognitive impairment improved their scores on some mental tests when they consumed cocoa flavanols. Importantly, researchers noted, the improvements in cognitive function were seen over a relatively short period of time, just eight weeks.

Another study tested the effects of cocoa consumption in 60 volunteers, average age 73, who had hypertension and/or diabetes. Although none had dementia, 17 suffered from a condition called impaired neurovascular coupling (NVC), a measure of blood flow in the brain as it relates to nerve cells (neurons). Researchers initially tested two levels of flavanols in cocoa, consumed twice a day for 30 days. Participants were encouraged to alter their diets to compensate for the extra calories in the cocoa. No significant differences were seen between the two types of cocoa, so the results from both groups were merged. Participants free of impaired NVC showed no significant benefits from cocoa consumption. But the small group of volunteers with impaired NVC saw dramatic changes after just a month of cocoa intake: Neurovascular coupling improved by more than double, and scores on standard cognitive tests jumped 30 percent.

Cocoa flavanols also are associated with improvements in blood pressure, blood glucose, and insulin resistance. So it isn’t clear whether the benefits in cognition seen in such studies are a direct consequence of cocoa flavanols or a secondary effect of these general improvements in health.

Coffee and Tea: Smart Sipping

The 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee concluded that coffee is safe to drink at typical levels of consumption, and suggested it could actually have health benefits. For example, a large Korean study reported that people drinking three to five cups of coffee daily were 41 percent less likely to show signs of coronary artery calcium than non-coffee drinkers. This calcification is an early indicator of the artery-clogging plaques that characterize atherosclerosis.

Coffee contains a wealth of phytochemicals with possible cardiovascular benefits. In turn, these are probably also important to brain health, as we’ve seen.

In one European study, men who consumed three cups of coffee a day suffered significantly less cognitive decline over 10 years than non-coffee drinkers. Coffee also appears to boost memory and reduce risk of stroke.

Caffeinating Your Brain

Other benefits from coffee consumption, perhaps not surprisingly, are associated with its caffeine content. Researchers have tested mice given water spiked with caffeine—the human equivalent of about five cups of coffee a day—versus mice given plain water to drink. The mice had been specially bred to develop an Alzheimer’s-like disease. After several months, the mice that received only water had difficulty navigating in mazes, while the caffeinated mice easily found their way out of the mazes.

Studies in humans have found that caffeine consumption in midlife may help to protect against cognitive decline later in life. Recent results from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging showed that caffeine intake was associated with better baseline global cognition among participants age 70 and older.

Another study concluded that older women who drank at least three cups of coffee daily were 18 percent less likely to develop problems with verbal recall and 33 percent less prone to memory problems than those who drank less coffee. Similar results were seen for tea, leading researchers to identify caffeine as the source of the benefit.

Tea As a Plant Food

Similarly, tea might benefit the brain in many different ways. Jeffrey Blumberg, PhD, senior scientist at Tufts’ HNRCA Antioxidants Research Laboratory, says, “As investigators continue to study the multiple effects that tea has on human health, more research supports tea’s potential in helping reduce the incidence of major diseases. In some respect, it is good to think of tea as a plant food.”

Studies support cognitive benefits from most types of tea, but especially green tea. One small clinical trial reported that green tea improves the connectivity between parts of the brain involved in tasks of “working memory.” Swiss researchers tested the effects of a beverage containing 27.5 grams of green tea extract (equivalent to about two cups of brewed green tea) against a placebo. Healthy young male volunteers were then faced with a battery of working-memory tasks, while their brains were monitored using magnetic resonance imaging. Men who had been given the beverage containing green-tea extract showed increased connectivity between the brain’s right superior parietal lobe and the frontal cortex. This effect on connectivity within the brain coincided with improvements in actual cognitive performance on working-memory exercises.

In another study of people with mild memory impairment, daily supplements of green tea extract plus L-theanine (an amino acid unique to tea) over four months improved memory and mental alertness compared to a placebo.

Studying a Green-Tea Compound

One reason green tea might be especially good for your brain is that it contains a polyphenol compound called EGCG (epigallocatechin-3-gallate). Researchers at the University of Michigan have reported that EGCG prevents the formation of potentially dangerous amyloid aggregates associated with the development of Alzheimer’s disease. A green-tea extract also broke down existing aggregates in proteins that contained metals—copper, iron, and zinc—associated with the disease.

British scientists have tested the effect of green tea extracts on “balls” of amyloid proteins created in the lab. The extracts caused the shape of the balls to distort in such a way that they could no longer bind to nerve cells and disrupt their functioning.

What About Wine?

You may have heard about a compound called resveratrol, found in red wine and grape juice. It is a type of polyphenol produced as part of a plant’s defense system against disease. For example, German researchers tested supplements of 200 milligrams of resveratrol daily for six months versus a placebo in 46 cognitively healthy people, ages 50 to 80. At the end of the study, participants randomly assigned to the resveratrol supplements scored better on memory tests and showed greater functional connectivity in their brains.

Scientists have shown that the polyphenols in red wine block the formation of proteins that build the toxic plaques found in the brains of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. These red-wine compounds also reduce the toxicity of existing plaques. Natural chemicals found in red wine as well as in green tea can interrupt the process by which Alzheimer’s proteins latch onto brain cells.

Keep in mind, however, that research on resveratrol is in the very early stages, and it may be that benefits are associated only with amounts impossible to consume except from supplements. That is the case, for example, of recent research on resveratrol and changes in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s disease (see Box 4-5, “Resveratrol Affects Alzheimer’s Proteins”).

Like all alcoholic beverages, moreover, wine should be consumed only in moderation—no more than two glasses a day for men, and one for women.

Hydrating Your Brain

The most important beverage for your brain is plain old water—and you might not be getting enough. Older people may be less sensitive to thirst, so it’s especially important for them to stay hydrated.

Dehydration has negative effects on your mood and cognitive performance, including memory, attention, and motor skills. Research on hydration and brain function—especially on positive effects of drinking more fluids—is limited and contradictory, however. The safest bet is to make sure you drink plenty of fluids (coffee and tea count, too) that don’t add calories, and to pay attention to your body’s thirst signals.

Fish as Brain Food

Seafood, especially the fatty fish high in heart-healthy omega-3s, seems to be “brain food.” Even if you’ve never been a big seafood eater, it’s not too late to reduce your risk of cognitive impairment and dementia by eating more fish. In fact, a recent study reports that this dietary change may be more beneficial later in life.

Researchers studied 1,566 Chinese adults, ages 55 and older, who completed a cognitive screening test and food questionnaires. They were followed for a little over five years. Age was found to significantly modify the association between fish consumption and cognitive change: Among adults ages 65 and older, those who ate one or more weekly serving of fish saw a slower rate of cognitive decline compared to those consuming less fish. The difference was equivalent to what would be expected from 1.6 years of difference in age. Fish consumption was also associated with a slower decline in composite and verbal memory scores. No associations were observed, however, among those ages 55 to 64.

People at higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s because of genetic factors might also benefit more from eating more fish (see Box 4-6, “Seafood May Help Protect Some at Greater Alzheimer’s Risk”).

The Omega-3 Connection

It makes sense that seafood rich in the omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenioc acid (DHA) could be good for your brain, since fatty acids play an important role in brain health. DHA is the most prominent fatty acid in the brain, especially in the neurons of the cerebral cortex—the “gray matter” responsible for memory, language, and thinking.

The omega-3 fats in fish have been associated with cardiovascular health since it was first discovered that the Inuit of Greenland, who consume a diet rich in fish, have low rates of heart disease. Fish is also a key component of the Mediterranean diet.

Though a form of omega-3 called alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) found in plants can be converted in your body to the more complex types found in fish, this conversion is not very efficient. The best way to obtain EPA and DHA is to consume fish, especially fatty varieties such as salmon and mackerel (see Box 4-7, “Shopping for Seafood,” on page 49).

Are fish-oil pills, which also contain EPA and DHA, as beneficial as eating fish? We’ll weigh the evidence in the next chapter. But nothing beats eating more fish—in part because of what you don’t eat when fish is the entrée: Dining on salmon instead of a ribeye steak gives you healthy fat instead of saturated fat.

Preparing and Picking Your Fish

How you prepare your fish also may make a difference; studies have found that baked and broiled (or grilled) fish are more beneficial than fried fish. That is likely due to the extra calories and saturated or trans fat added to fried fish in the breading and frying process. The type of fish commonly used for frying may also be a factor: Cod and other whitefish varieties are much lower in omega-3 content than other types of fish

Shellfish generally falls short on omega-3s, too. Although shrimp, for example, is a lean source of high-quality protein, it is low in total fat and thus also low in omega-3 fatty acids. The omega-3 content of crab is somewhat higher, similar to that of light canned tuna, although it varies widely by species.

More Fish, More Omega-3s

The importance of omega-3s in general and DHA in particular to seafood’s cognitive effects was demonstrated in a Tufts study several years ago. It involved nearly 900 elderly men and women initially free of dementia who were screened for cognitive decline every two years. Following up an average nine years later, the researchers documented 99 cases of dementia, including 71 with Alzheimer’s disease.

Among the 488 participants who also completed a dietary questionnaire, those with the highest blood DHA levels reported that they ate an average of nearly three fish servings a week. Participants with lower DHA levels ate substantially less fish. Those with higher blood levels of DHA, as well as those eating the most fish, had a dramatically lower risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Subjects with the highest DHA levels had a 47 percent reduced risk of dementia and a 39 percent lower risk of Alzheimer’s.

Scanning Fish Eaters

People who eat more fish also literally have more “gray matter” than non-fish eaters. In a study using MRI scans, people eating broiled or baked fish, but not fried fish, on a weekly basis had greater volumes of gray matter in the brain’s hippocampus and frontal and temporal lobes. In subsequent cognitive testing, only 3.2 percent of those with the highest fish intake and greatest preservation of gray matter developed mild cognitive impairment or dementia. That was a sharp contrast to the 30.8 percent of non-fish eaters who’d suffered such cognitive decline. Average scores for “working memory” were significantly better among weekly fish eaters, too.

Researchers concluded, “Consuming baked or broiled fish promotes stronger neurons in the brain’s gray matter by making them larger and healthier. This simple lifestyle choice increases the brain’s resistance to Alzheimer’s disease and lowers risk for the disorder.”

Like other links between specific types of food and cognition, the recommendations to eat more seafood remain a work in progress. As science zooms in from general dietary patterns associated with brain health to particular foods and even individual nutrients, the research challenges mount. We still have no “magic bullet” against Alzheimer’s and dementia, but we continue to learn more about how to improve your odds.

The post 4. Brain Power Foods appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 4. Brain Power Foods »

Powered by WPeMatico