5. Nutrients in Supplement Form

Multivitamins and Your Brain

For many Americans, taking a multivitamin as “insurance” against nutritional shortfalls is a daily habit. Americans have been taking multivitamin/mineral supplements since the early 1940s, and an estimated one-third of all U.S. consumers take these regularly. Multivitamins account for almost one-sixth of all purchases of dietary supplements and 40 percent of all sales of vitamin and mineral supplements—nearly $6 billion annually.

It would seem to make sense that taking a pill containing the nutrients believed to be beneficial for your brain, such as those found in a multivitamin or in various specific supplements, would have the same effects as eating healthy foods. Many studies testing that premise for other health benefits, however, have proven disappointing. For reasons scientists can’t fully explain, vitamins and minerals consumed as part of foods seem to affect the body differently than when popped in pill form. It may be that synergistic relationships between nutrients trigger benefits that are not present in isolation.

Putting Multivitamins to the Test

Some scientists have looked at whether the combination of vitamins and minerals in a daily multivitamin might help protect your aging brain. But a recent study using data from the Physicians’ Health Study II suggests the answer is, “Probably not.”

Participants were 5,947 men, average age 71.6, who were randomly assigned to receive either a daily multivitamin or a placebo. The analysis combined five tests of global cognitive function as well as testing verbal memory. Over an average follow-up of 8.5 years, changes in mental function were no different in the multivitamin group than in those taking a placebo. Researchers concluded, “These data do not provide support for use of multivitamin supplements in the prevention of cognitive decline.”

Fish Oil from Pills

Eating more omega-3-rich fish, as we’ve seen, has manifold health benefits, including replacing less-healthy entrée options in your diet. But if the key benefit is increasing your intake of DHA and EPA, the two most important omega-3s found in fish, could taking a fish-oil pill have similar brain benefits? This question has been more extensively studied than most promises of brain benefits from supplements, but to date the evidence is mixed, at best. Most recently, in fact, a large study using data from the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) of supplements against age-related macular degeneration failed to find any cognitive benefits from fish-oil pills, or from the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin (see Box 5-1, “Fish-Oil Supplements Fail to Prevent Mental Decline”). Because of the makeup of the study population, however, this otherwise-definitive-seeming research may not yet be the final word. This was a well-nourished, highly educated population, and it could be that supplementing an already healthy diet of highly educated individuals isn’t going to have much added benefit on cognition.

For example, a 2015 study took a retrospective look at the effects of fish-oil supplements on brain activity and behavior in 819 older adults who participated in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Every six months, participants completed standard cognitive tests for memory and other mental abilities and underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. Individuals who took fish-oil pills had significantly less brain atrophy and better scores on cognitive tests than individuals not taking the supplements. But these beneficial effects were seen only in those with normal cognitive abilities when the study started. Participants who already displayed mild cognitive impairments or Alzheimer’s saw no improvement from taking the supplements.

Fish Oil for Healthy Brains

It’s easy to see why consuming DHA (and, possibly, to a lesser extent, the related omega-3 EPA) might benefit the brain. Lipids, a collective term for fats and oils, make up about 50 to 60 percent of the brain’s dry weight, and the omega-3 fatty acid DHA, which is found in fish oil, is the most abundant fatty acid found in the nerve cell membrane. The DHA composition of the brain decreases with age, however, as a result of the cumulative effects of oxidative damage.

It may be that taking extra DHA in pill form while your brain is still relatively healthy can slow this decrease and protect your cognition. Among healthy older adults not already suffering cognitive decline, randomized controlled trials have shown that supplements of DHA (800-900 milligrams/day) can improve verbal, visuospatial, and episodic memory. A lower dose of DHA—similar to that in most commercial fish-oil supplements—did not influence cognitive function, however.

On the other hand, a review of three high-quality clinical trials totaling 3,536 participants found no significant differences in the performance of cognitive tasks between individuals taking fish-oil supplements or placebo. Again, doses were relatively low—ranging from 400 to 700 milligrams daily. Only small, insignificant improvements in performance on tests of memory, executive function, and mental processing speed were found for individuals given fish-oil supplements.

Little Evidence Otherwise

The evidence is even less convincing for benefits of fish-oil supplements among people already diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s. Only a few small studies have suggested that omega-3 supplements help these patients any more than a placebo.

In one small Swedish study, for example, omega-3 supplements slowed mental decline in people with very mild Alzheimer’s disease. No effect, however, was observed in people with more advanced forms of the disease.

Another small study in Japan looked at the effects of omega-3 DHA plus ARA (arachidonic acid), an omega-6 fatty acid, in patients with mild cognitive impairment. After 90 days, those who received supplements rather than a placebo showed significant improvements in immediate memory and attention. Those whose cognitive impairment was due to brain lesions improved the most, but those with early Alzheimer’s disease did not benefit from the supplements.

If you don’t enjoy eating seafood, it may be tempting to pop a pill instead of consuming salmon and other fatty fish. But don’t count on the pills to protect your brain—and the evidence is particularly thin for people already suffering cognitive impairment.

The ABCs of Extra B Vitamins

As with omega-3s, it makes biological sense that taking supplemental B vitamins would benefit your brain. Some of the earliest research on vitamin B12 deficiency connected it to central nervous system problems. Vitamins B6 and B12 and folate are critical components of a metabolic cycle important for DNA synthesis. Deficiencies of these vitamins are associated with high levels of homocysteine, an amino acid associated with cardiovascular disease that may also be linked to cerebrovascular disease, including stroke and vascular dementia. Some studies have also found high levels of homocysteine in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients.

But taking B vitamin supplements, even when they succeed in lowering homocysteine levels, doesn’t necessarily protect the brain. The evidence from such studies is complex and even contradictory.

Linking Cognition and Low B12

People with low levels of vitamin B12 do seem more likely to suffer cognitive problems. For example, one study found that people with insufficient levels of B12 were at greater risk of cognitive decline over nearly five years of follow-up than those with adequate levels of the vitamin. Very low levels of B12 also predicted decreased total brain volume. Another study reported that older people with low—but still normal—blood levels of B12 were six times more likely to experience brain atrophy as those with the highest blood levels of the vitamin.

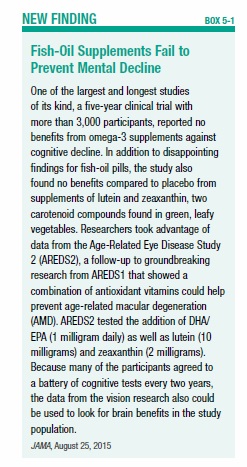

This could be of particular concern for older adults, who often have difficulty absorbing B12 from food because of changes to the gastrointestinal system due to aging. Certain medications, such as stomach-acid blockers, can also contribute to the risk of B12 deficiency. Federal dietary guidelines recommend that people age 50 and older consume foods fortified with vitamin B12 and/or B12 supplements (see Box 5-2, “Foods High in Vitamin B12”).

Tufts scientists have found that even if you’re only a little low in vitamin B12, you might be at greater risk for cognitive decline than previously thought. Their study divided 549 participants, average age 75, into five groups based on their blood levels of vitamin B12. Men and women in the second-lowest group did not fare any better in terms of cognitive decline than those with the worst vitamin B12 blood levels. Over an eight-year period, scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMMSE) tests declined slightly overall. But average declines were significantly faster in both the lowest and second-lowest groups ranked by vitamin B12 status.

Senior author Paul F. Jacques, DSc, commented, “While we emphasize our study does not show causation, our associations raise the concern that some cognitive decline may be the result of inadequate vitamin B12 in older adults, for whom maintaining normal blood levels can be a challenge.”

More Not Necessarily Better

As with fish oil pills, it makes sense that B vitamin supplements might help protect the brain, since too little B12 is associated with poorer cognition. But giving people extra B vitamin supplements has not always paid dividends in brain health (see Box 5-3, “No Brain Bonus from Correcting B12 Deficiency”).

In one recent analysis, researchers combined results from 11 previous trials of B vitamins and cognition totaling 22,000 participants. They found, as expected, that B-vitamin supplements decreased homocysteine levels by an average 25 percent. But effects on mental ability were small, amounting to only one week of cognitive aging per year of supplementation.

In another study, Dutch researchers used data from 2,919 people, average age 74, with elevated levels of homocysteine. Participants were randomly assigned to a placebo or a daily tablet containing 400 micrograms of folic acid and 500 micrograms of vitamin B12. Participants given the supplements saw their homocysteine levels decline almost four times as much as the control group’s. But after two years, cognitive scores between the two groups in a battery of tests differed only slightly.

On the Other Hand

It could be that extra B vitamins benefit only certain subgroups of people, such as those initially with a low intake of B vitamins or elevated homocysteine levels. One positive study, dubbed VITACOG, compared the effects of high-dose B-complex supplements and placebo in older adults. Those given the extra B vitamins experienced slower brain atrophy. As in other studies, the benefits were greatest among subjects with elevated blood levels of homocysteine.

A British study also reported that supplemental doses of folate, B6, and B12 were associated with significantly less brain atrophy over time compared to placebo. Greater rates of brain atrophy were associated with lower cognitive test scores at the end of the study.

It’s Complicated

Recent research has also suggested that genetic factors may influence the interaction between cognitive performance and B vitamin status. Until we know more, make sure that you’re consuming adequate amounts of B vitamins from foods (consider adding fortified foods and supplements to your diet if necessary if you’re over age 50). But don’t bother taking mega-doses in hopes of turning back the clock on your brain.

In fact, too much of a good thing—folate, another important B vitamin—might actually be bad for your brain, according to an Australian study. Participants with both low vitamin B12 and high folate levels were more than three times as likely to have impaired cognitive performance as those with normal levels. Participants with high folate levels, but normal vitamin B12, were also somewhat more likely to have impaired cognitive performance.

Vitamin D Disappointments

No vitamin has engendered so much excitement and such a flurry of research in recent years as the so-called “sunshine vitamin,” vitamin D. Your body can synthesize vitamin D from exposure to sunlight, but many people don’t get enough from either sun exposure or their diet. Vitamin D is known to be vital to strong bones, and low levels of vitamin D have been linked to a wide range of chronic diseases.

What about the brain? In a review of the evidence, researchers reported that in 18 out of 25 cross-sectional observational studies, individuals with low vitamin D levels did more poorly on tests of cognitive functioning or displayed a higher frequency of dementia than individuals with higher blood levels of the vitamin. Similarly, four out of six prospective observational studies showed a higher risk of cognitive decline after a follow-up period of four to seven years in participants with lower vitamin D levels at baseline.

But the promising findings of observational studies of vitamin D have mostly failed to find support in more rigorous clinical trials, considered the “gold standard” of scientific research. A 2016 editorial in JAMA Internal Medicine put it this way: “The vitamin D story seems to be following the familiar pattern observed with antioxidant vitamins,” such as vitamin E, beta-carotene, and vitamin C. In that pattern, the editorial noted, initial enthusiasm for supplementation, reinforced by observational studies “showing, essentially, that healthy people have higher vitamin levels,” fails to be supported by randomized clinical trials or meta-analyses.

Cause Versus Effect

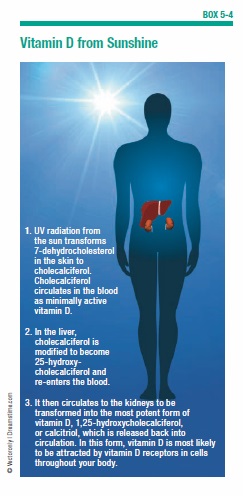

As the previous commentary underscores, it can be challenging to determine whether low levels of vitamin D are the cause of health problems or an effect of poor health and aging. Older adults and people in poor health often have trouble consuming adequate nutrients and spend less time outdoors in the sun. The skin naturally synthesizes vitamin D when exposed to sunlight—hence the “sunshine vitamin” nickname. If you’re stuck indoors, you are more likely to be deficient (see Box 5-4, “Vitamin D from Sunshine”).

Without sun exposure, it can be difficult to obtain adequate vitamin D from food alone (see Box 5-5, “Getting Your Vitamin D,” on page 53). Those at risk for vitamin D deficiency may want to consider supplements to reach the targets recommended by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The IOM says people ages 70 and older should aim for a daily intake of vitamin D of 800 IU (International Units), 600 daily units for those age 69 years and younger. But most older people, the IOM advises, do not need routine measurement of their blood levels of vitamin D.

Beyond the benefits of avoiding deficiency, however, there is little real evidence that vitamin D supplementation boosts brain power or that there are benefits to intake beyond that necessary to avoid deficiency. So you should make sure you’re getting enough vitamin D—but there’s no reason to overdo it.

Dangers of Deficiency

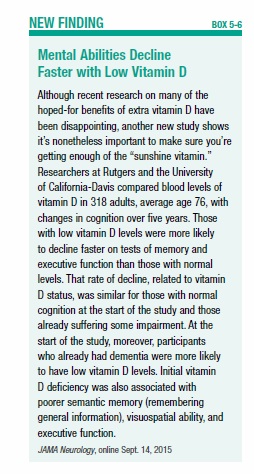

It is clear that people with too little vitamin D are more likely to suffer cognitive impairment, even though the cause and effect in that connection are tough to untangle (see Box 5-6, “Mental Abilities Decline Faster with Low Vitamin D,” on page 58).

In one study, the largest of its kind, older individuals deficient in vitamin D were significantly more likely to develop dementia and Alzheimer’s over almost six years of follow-up than individuals with higher blood levels of the vitamin. Researchers characterized the results as “surprising” and said the association was twice as strong as anticipated.

The study examined long-term outcomes in 1,658 participants, ages 65 and older, in the Cardiovascular Health Study whose blood levels of vitamin D were tested for deficiency (defined as about 10-20 nanograms per milliliter [ng/mL]) and severe deficiency (below 10 ng/mL). Compared to those with adequate vitamin D, those who were classified as deficient were 53 percent more likely to develop any type of dementia and at 69 percent greater risk of Alzheimer’s. With severe vitamin D deficiency, comparative risk rose sharply, to 125 percent greater likelihood of dementia and 122 percent of Alzheimer’s.

Researchers cautioned, however, that this kind of “prospective” study can’t prove cause and effect; it is possible that vitamin D deficiency represents a consequence, rather than a cause, of cognitive deficits in elderly individuals.

More Reasons to Get Enough

Another study, in Italy, reported that over a six-year span, older adults with the lowest blood levels of vitamin D were at greater risk for declines in thinking, learning, and memory. Participants who were severely deficient in vitamin D were 60 percent more likely to suffer substantial overall cognitive decline and 31 percent more prone to decline in tests of executive function than those with adequate levels.

Recent research has even suggested that vitamin D helps clear beta-amyloid, the substance that forms the brain plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease. It may help prevent the degeneration of brain tissue by promoting the formation of neurons and maintaining the body’s levels of calcium. It has also been proposed that vitamin D protects against age-related inflammatory changes in the brain’s hippocampus.

Fresh Thinking on Antioxidants

You will still see the benefits of “antioxidants” touted in magazines and popular health books, but nutrition scientists now tend to think of these compounds not solely for their “antioxidant” capacity. By trapping compounds called “free radicals,” antioxidants prevent oxidative damage to cells—including cells in the brain. But this may not be the primary benefit of nutrients loosely grouped as “antioxidants.”

For example, most of the phytochemical nutrients like flavonoids and anthocyanins we looked at in the previous chapter are also antioxidants. So are such familiar nutrients as vitamins C and E and beta-carotene. The health effects of these compounds go well beyond their ability to counter free radicals.

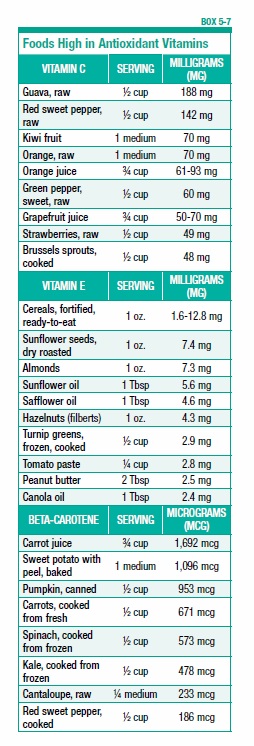

Since many of the foods high in antioxidants also seem to have brain benefits, such as fruits and vegetables (see Box 5-7, “Foods High in Antioxidant Vitamins,” on page 59), scientists have explored whether supplements of these same compounds might have similar protective effects. To date, the results are mixed—certainly no reason to switch from fruits and vegetables to pills. And since the mechanisms of the protective effects of fruits and vegetables on the brain remain not fully explained, the only way to be sure to experience them is by consuming whole foods.

Looking for Brain Benefits

An exhaustive review of the evidence of how antioxidant nutrients affect cognitive performance narrowed 850 eligible studies down to the 10 best. The most convincing evidence, scientists concluded, involved blood levels of selenium and intake of vitamins C and E, and carotenes. A decrease in selenium levels in the blood over nine years was associated with an accelerated decline in global cognition, attention, and psychomotor speed. People in the highest one-fifth of intake of vitamins C, E, and carotenes exhibited a slower rate of global cognitive decline over three years.

Other studies showing evidence of beneficial associations of higher dietary intake of vitamin E and flavonoids, as well as higher blood beta-carotene levels, were judged to be of lower quality. The review concluded, “There is a possibility for protective effects of antioxidant nutrients against decline in cognition in older people, although the supportive evidence is still limited.”

Supplements and Memory

What about consuming antioxidant nutrients in supplement form? Another study reviewed a lengthy randomized trial of supplementation, involving more than 4,000 people. Those in the antioxidant supplement group received 120 milligrams of vitamin C, 6 milligrams of beta-carotene, 30 milligrams of vitamin E, 100 micrograms of selenium, and 20 milligrams of zinc daily. Five years later, participants underwent a battery of cognitive tests. Those who had been in the antioxidant group scored better in episodic memory (recollection of events that happened to you) than those who received a placebo; however, nonsmokers and those low in vitamin C at the beginning of the trial scored higher on verbal memory (recalling words from a list).

Vitamin E and Alzheimer’s

Some recent evidence indicates that extra vitamin E might slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease—but it doesn’t mean healthy people should run out and buy vitamin E supplements. A study of more than 600 mostly male veterans at 14 VA hospitals across the country compared a placebo with three treatments for patients with mild or moderate Alzheimer’s: High-dose (2,000 IU daily) vitamin E supplements; a combination of vitamin E and memantine, a drug that’s been shown to have modest benefits in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s; and memantine alone. Only the vitamin E group saw any benefit, a small but statistically significant difference in tests of functional impairment over a period of more than two years. All three groups declined in their ability to perform tasks of daily living, but the vitamin E group declined the least.

The results, experts note, are specific to individuals already suffering with moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease and don’t generalize to a healthy population. Other specific trials of vitamin E supplementation have failed to find a link between vitamin E supplements and risk of cognitive decline.

There is also reason for caution about taking vitamin E supplements. Two clinical trials have found an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke in participants taking vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol). Two meta-analyses of randomized trials also have raised questions about the safety of large doses of vitamin E, including doses lower than the safe upper limit (UL). These meta-analyses linked supplementation to small but statistically significant increases in all-cause mortality. Results from the large SELECT trial also showed that vitamin E supplements (400 IU/day) may harm adult men in the general population by increasing their risk of prostate cancer.

Your Brain and Beta-Carotene

Supplements of beta-carotene, which the body converts into vitamin A, might have brain benefits, but only when taken for an extended period of time. Researchers reported that men who took 50-milligram supplements of beta-carotene every other day for an average of 18 years did significantly better on cognitive tests, especially those measuring verbal memory, than those taking a placebo. The benefit was the mental equivalent of being one year younger. But no similar protection against brain aging was observed in individuals given supplements for only a year.

As with vitamin E, however, there is a caution: Smokers should not take extra beta-carotene because of increased risk of lung cancer. Two well-designed clinical trials have reported that supplements of beta-carotene, alone or in combination with vitamin E supplements, increased the risk of lung cancer in smokers, compared to placebo.

Other Carotenoids

Researchers have also investigated whether other carotenoids, proven to be beneficial for your eyes, could also help protect your brain. Lutein and zeaxanthin, carotenoid compounds found in leafy greens and other foods, form important pigments in the macula of the eye; supplements designed to reduce the risk of macular degeneration contain both. Lutein and zeaxanthin are the only carotenoids that cross the blood-retina barrier, and also accumulate in the human brain.

A small study compared macular pigments in 36 Alzheimer’s patients and 33 healthy controls of the same age. The Alzheimer’s patients were found to have significantly lower amounts of macular pigment and lower blood levels of lutein and zeaxanthin. They also had poorer vision and a higher incidence of macular degeneration.

Most recently, however, the same Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) that proved disappointing about fish oil pills also failed to find cognitive benefits from lutein and zeaxanthin (see Box 5-1, on page 52). The same caveat about the study population applies to these conclusions, though, so scientists are continuing to look at these carotenoids.

Food, Not Pills

While many of these findings are promising, more research is needed before recommending any antioxidant supplements; antioxidants are best obtained from food. When you eat antioxidant-rich foods such as fruits and vegetables, you are getting a complex mix of nutrients, including fiber, that just can’t be packed into a pill.

That same lesson applies to any pill promoted as a “magic bullet” to protect your aging brain. Taking a daily multivitamin won’t hurt you, but an overall healthy diet is better for your brain than counting on “insurance” from a supplement. (Many of the multivitamins that specifically tout their brain benefits rely on less-proven ingredients that don’t actually “supplement” what the body needs at all; we’ll look at these claims in the next chapter.) With advice from your healthcare professional, you might decide to supplement your dietary intake of vitamin B12 and/or vitamin D, which you could be falling short on as you age.

But the evidence simply is not strong enough to single out any specific nutrient taken in pill form to safeguard your brain. As we’ll see in the next chapter, the science behind most “supplements” touted specifically for cognition is, at best, even thinner.

The post 5. Nutrients in Supplement Form appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 5. Nutrients in Supplement Form »

Powered by WPeMatico