3. Fats, Carbohydrates, and Protein

Basic Nutrients

Before you worry about getting enough of specific vitamins or minerals, it’s smart to consider the dietary roles of the three most basic forms of nutrients: fats, carbohydrates, and protein. These are so fundamental to the nutritional quality of the foods we eat that their relative proportions are actually used to calculate how many calories are in a food. Rather than measure calories by literally burning up a food, most food manufacturers simply do the math: Fats have nine calories per gram, while carbohydrates and protein contain four calories. (When fiber, a form of carbohydrate, passes through the body without being digested, its calories don’t “count”).

Much of the ever-evolving debate about the components of a healthy diet revolves around the proper proportions of these three key nutrients. Beginning in the 1980s, an overemphasis on reducing total fat (rather than saturated fat, which contributes to unhealthy cholesterol levels) had unanticipated consequences for the nation’s health: When consumers replaced dietary fats of all kinds with processed carbohydrates, obesity rates increased.

That was followed by popular diets focusing on reducing “carbs,” even at the expense of nutrient-rich carbohydrate-containing foods such as fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Along with that trend came an increased emphasis on consuming protein, which continues today.

Stop Worrying About Total Fat

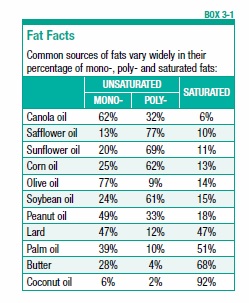

But many people still haven’t gotten the message that not all fat is bad for you or for your brain. Some types of fat—monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, like those found in liquid vegetable oils, nuts, and avocados—are actually good for your heart. As we’ve seen, that probably means they are also good for your brain. Fat is also an important component of cell membranes in the brain and of the myelin coating on neurons, which speeds up the transmission of information in the nervous system (see Box 3-1, “Fat Facts”).

The latest Dietary Guidelines for Americans, in fact, reversed 35 years of nutrition policy by omitting any recommended limit on total fat intake. In 1980, the federal Dietary Guidelines first recommended limiting dietary fat to less than 30 percent of calories; in a 2,000-calorie daily diet, that advice translated to a maximum of 65 grams of fat per day. The 1980 recommendation was revised in the 2005 guidelines to a range of 20 percent to 35 percent of calories from total fat. The percentages used in the Nutrition Facts panel, however, continue to be based on the 1980 recommendation of 30 percent or 65 grams.

Smart Fat Selections

Instead of focusing on total fat in your diet, experts advise concentrating on substituting healthier mono- and polyunsaturated fats for saturated fats. It’s no coincidence that the Mediterranean-style diet is rich in healthy unsaturated fats. Scientists have found that increasing the intake of monounsaturated fats, as in olive oil, and of polyunsaturated fats, as in nuts, can help the brain perform its vital functions.

Participants in the PREDIMED-NAVARRA trial who followed a Mediterranean-style diet and also consumed at least four tablespoons of extra-virgin olive oil a day scored significantly better on two tests of mental abilities than a control group that was assigned to a low-fat diet. Those assigned to a Mediterranean plan supplemented with about a quarter-cup of walnuts, almonds, and hazelnuts daily also scored better than the control group. After more than six-and-a-half years of follow-up, fewer participants consuming either of the Mediterranean-style diets were diagnosed with dementia than individuals in the control group.

In the study, the Mediterranean groups actually consumed more total fat than the controls—the difference was that the fat was primarily heart-healthy monounsaturated (olive oil) or polyunsaturated (nuts). This finding further supports the apparent brain benefits of switching fats, not just cutting down on fats of all types.

Unsaturated Benefits

In another study, of 966 subjects, scientists compared adherence to a Mediterranean-style eating pattern to white matter hyperintensity volume (WMHV), a marker for small-blood-vessel damage in the brain. Participants completed food-frequency questionnaires to assess their diets and underwent MRI scans of their brains.

After adjustment for other risk factors, only one component of the Mediterranean diet was independently associated with WMHV: The ratio of monounsaturated fat to saturated fat. As the dietary share of monounsaturated fat rose versus saturated fat, WMHV declined. That suggests, researchers concluded, the overall dietary pattern rather than individual nutrients is responsible for healthier brains.

Polyunsaturated fats also include the omega-3 fatty acids found in fish oil, which have been the subject of much scientific study for possible brain benefits. We’ll look specifically at these fats in chapter 5.

Continue to Avoid Saturated Fat

Butter has been making a comeback in the popular press; Internet outlets and even the New York Times have seized upon a few studies casting doubt on the long-standing association between saturated fat and unhealthy cholesterol levels. But Tufts experts say, not so fast.

“We have strong data that substituting polyunsaturated fats for saturated fats decreases the risk of heart disease,” says Alice H. Lichtenstein. “We also have strong data that substituting carbohydrates, particularly refined carbohydrates, for saturated fats does not reduce risk.” When data from studies that examine the effects of substituting polyunsaturated fats are analyzed together with those substituting carbohydrates for saturated fats, she says, the results can cause confusion.

The Cognition Case Against Saturated Fat

If saturated fat is bad for your heart, it’s probably also bad for your brain. A recent review of the science published in Neurobiology of Aging generally supported a link between saturated fat intake and risk of Alzheimer’s and dementia. Although some findings were mixed, saturated fat intake was positively associated with Alzheimer’s risk in three of four cohort studies.

Scientists noted several possible explanations for the lone outlier, the Rotterdam Study, that actually found a slight inverse relationship between saturated fat intake and Alzheimer’s risk: The limited variability in saturated fat intake, with little difference between the highest and lowest groups, may have blunted any observable effects. Rotterdam participants also had an unusually high vitamin E intake, which some studies have associated with reduced Alzheimer’s risk. The review also found a positive association between saturated fat intake and risk of dementia (one of two studies reviewed), risk of cognitive decline (two of four studies), and risk of mild cognitive impairment (one of two).

Previously, findings from the Women’s Health Study showed that women who ate the most saturated fat had poorer scores on cognitive tests than those who consumed the least, and were about 65 percent more likely to experience a decline in mental performance over time. The total amount of fat intake did not really matter, but the type of fat did.

Understanding Cholesterol

Why might saturated fat be bad for your heart and brain when other types are not—and may even be beneficial? Along with trans fat, saturated fat is believed to contribute to unhealthy cholesterol in your bloodstream, called “serum” cholesterol. That cholesterol—a waxy, fat-like substance—is not the same as the dietary cholesterol listed on Nutrition Facts panels. The latest expert guidance largely dismisses concerns over intake of dietary cholesterol, such as found in eggs and shellfish.

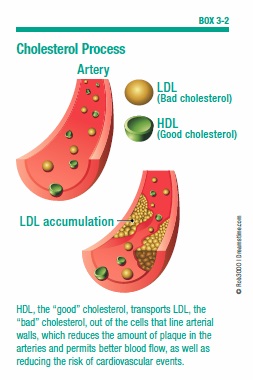

Your body needs a little serum cholesterol to make bile acids, hormones, vitamin D, and to maintain other essential physiological processes. Your cells need it for the proper permeability and fluidity of their membranes. But, your body can make all the cholesterol it needs, primarily in the liver; any extra cholesterol can get deposited in artery walls.

Hardening Your Arteries

This accumulated cholesterol eventually forms plaque, which narrows blood vessels and makes them less flexible—resulting in atherosclerosis, popularly known as “hardening of the arteries.” Since your brain uses such a high proportion of your body’s blood flow, anything that affects your circulation also impacts your brain (see Box 3-2, “Cholesterol Process”).

The Diabetes Heart Study-Mind recently reported that such changes in “the vascular system” were related to cognition even before the changes became clinically apparent and treatable. Researchers measured the amount of calcified plaque in participants’ coronary arteries when the study began. Seven years later, a battery of cognitive tests measured subjects’ memory, processing speed, and executive function: Those with greater plaque at baseline scored lower on those mental tests.

Behind the Numbers

Cholesterol tests are a common fact of life as you get older, and if your numbers get too high, your doctor will probably prescribe statin medications. But what do those numbers really mean?

Just as oil and water don’t mix, fatty serum cholesterol and watery blood can’t directly combine. So, cholesterol in your blood rides along in packages called lipoproteins, which have cholesterol inside and protein on the outside. The two main types of these lipoproteins are what are actually measured when the lab tests your cholesterol:

- Low-density lipoprotein, or LDL, carries cholesterol to your tissues, earning it the nickname of “bad” cholesterol. When too much LDL circulates in the blood, it can slowly build up in the walls of the arteries that supply blood to the heart and brain. According to the American Heart Association, an LDL cholesterol level of 130 to 159 mg/dL (milligrams per deciliter) is “borderline high,” 160 to 189 mg/dL is “high,” and 190 mg/dL and above is “very high.”

- High-density lipoprotein, or HDL, gets labeled “good” cholesterol because it carries cholesterol from tissues to the liver, which removes it from the body. A level of at least 40 mg/dL for men and 50 mg/dL for women is associated with lower risk; the higher the HDL, the better.

- Triglycerides are another form of fat in your blood. Calories you consume that are not used immediately by the body’s tissues are converted to triglycerides and transported to fat cells to be stored. Hormones regulate the release of triglycerides from fat tissue to meet the body’s energy needs between meals. An excess of triglycerides in the blood, a condition called hypertriglyceridemia, is linked to the occurrence of coronary artery disease in some people. According to the American Heart Association, a triglyceride level of 150 to 199 mg/dL is “borderline high,” 200 to 499 mg/dL is “high,” and 500 mg/dL and above is “very high.”

Improving Your Numbers

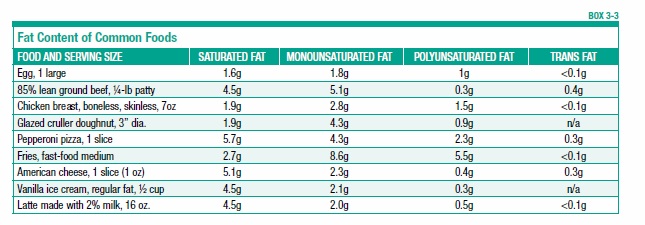

While statin medications are powerfully effective for most people in improving unhealthy cholesterol levels, you can also help by adjusting your diet. To reduce LDL cholesterol, the American Heart Association recommends limiting saturated-fat intake to five to six percent of your total calories (see Box 3-3, “Fat Content of Common Foods,” on page 33). For most people, this means cutting saturated-fat intake roughly in half; the current average intake is 11 percent of calories. In a 2,000-calories daily diet, five to six percent of calories would equal 100 to 120 calories a day from saturated fat. That translates to roughly 11 to 13 grams of saturated fat per day, or a little less than the saturated fat in two tablespoons of butter.

It’s key to replace those unhealthy fats with healthy ones—not, as in the fat-free fad of recent years, with refined carbohydrates. For best results, the experts advise, substitute polyunsaturated fat for saturated fat. Next best is monounsaturated fat.

You also should avoid trans fats, found in partially hydrogenated oils used in some baked goods and packaged products. Both saturated fats and trans fats raise LDL.

Good Cholesterol for Cognition

Scientists continue to investigate the role of the “good” HDL cholesterol in your body. Some studies have failed to find benefits from boosting HDL cholesterol, suggesting that this number may actually be just a marker for an overall healthy lifestyle.

On the other hand, a study of 3,673 men and women suggests that higher HDL cholesterol might benefit the brain. Researchers measured cholesterol levels twice, at average ages 55 and 61, and short-term verbal memory was tested at each age. Initially, participants with low HDL (less than 40 mg/dL) scored lower on the memory test than those with high HDL (60 mg/dL or higher), but the difference wasn’t statistically significant. After five years, however, the difference increased to become significant. Moreover, individuals whose HDL levels declined during the five-year interval were more likely to also show a decline in memory performance than those whose HDL levels did not change.

The researchers speculated that HDL might protect cognitive function by reducing the risk for stroke and vascular disease, or HDL could moderate beta-amyloid, which is associated with plaques in the brain. Additionally, HDL may have anti-inflammatory or antioxidant effects, which could help to prevent the degeneration of the brain’s neurons.

You can maintain healthy HDL levels by not smoking, avoiding trans fats, and losing weight. Factors thought to boost HDL include exercise, moderate alcohol consumption, and intake of soluble dietary fiber, such as that found in oats, vegetables, fruits, and legumes.

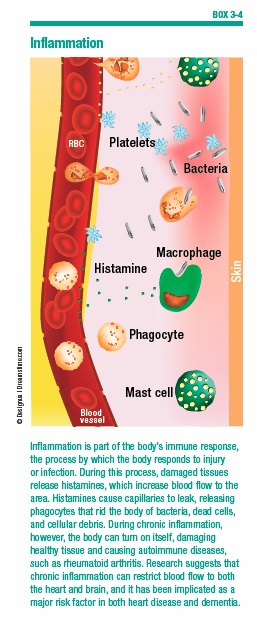

Cholesterol and Inflammation

Scientists are also investigating the role of inflammation in the body and how this might interact with cholesterol. Chronic inflammation in the blood vessels can allow LDL cholesterol to invade, producing a vicious circle of increasing inflammation. Not surprisingly, markers of inflammation in the bloodstream also have been linked to cognitive decline and abnormalities in brain structure. As people age, the regulatory processes that combat inflammation become less effective, resulting in greater inflammatory responses and damage.

Keys to Chronic Disease

A range of chronic diseases related to diet, obesity, and lack of physical activity—notably cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes—are associated with systemic inflammation. Fat (adipose) tissue is a source of chemicals that promote inflammation. Many risk factors for decline in brain health—including free radicals (countered by antioxidants) and homocysteine (related to B vitamins)—can trigger inflammatory responses in the brain. So can oxidized lipids, related to unhealthy cholesterol levels.

The best strategy for combating inflammation is to make the healthy lifestyle changes that can reduce your risk of chronic disease. We’ll look at these risk factors in-depth in later chapters (see Box 3-4, “Inflammation”).

What About Omega-6s?

You may have seen warnings, on the Internet or in popular nutrition books, about the dangers of omega-6 fatty acids, which supposedly cause inflammation. While similar to the heart-healthy omega-3s found in fish oil, omega-6s have a slightly different chemistry. Liquid vegetable oils high in polyunsaturated fats, including corn, safflower, sunflower, and soybean oils, are high in omega-6s.

It’s true that some of the main omega-6 fatty acids are involved in the early stages of inflammation, but they also give rise to anti-inflammatory molecules. According to a scientific advisory by the American Heart Association based on a review of the evidence, “omega-6 fatty acids are in fact heart-healthy and are not pro-inflammatory.”

In fact, a recent review published in Circulation found that people who swap 5 percent of the calories they consume from saturated fat sources, such as red meat and butter, with foods containing linoleic acid—the primary omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid in the Western diet—saw a 9 percent lower risk of coronary heart disease events. Linoleic acid-containing foods include walnuts and walnut oil, flaxseeds, and soybeans and soybean oil. Switching from saturated fat to linoleic acid was also associated with a 13 percent lower coronary heart disease mortality risk. Since what’s good for the heart is good for the brain, this suggests there’s no reason to fear omega-6 fats.

Good and Bad “Carbs”

Following the “fat-free” fervor that swept the nation’s nutritional mindset, the next target for a healthy-eating fad was carbohydrates. Going “low-carb,” it was said, would lead to dramatic weight loss and other health benefits. In extreme forms, this fad meant cutting back on healthy sources of carbohydrates such as fruits and vegetables.

Not surprisingly, the reality about the health effects of carbohydrates is more complicated than such fads take into account. Carbohydrates, which include sugars, starches and fiber, provide energy for the body, especially the brain and the nervous system. To obtain that energy, enzymes break down carbohydrates into glucose (blood sugar) during digestion, which the body then uses to fuel its many functions.

So your brain needs some carbohydrates, and actually suffers when you don’t get enough. Dietary fiber, a type of carbohydrate, has beneficial effects on your cardiovascular system that can in turn help protect your brain. Sugar, however, especially in the form of added sugar that comes with no extra vitamins or minerals (versus, for example, the sugar in a piece of fruit), is increasingly seen as a key contributor to chronic disease. And research is beginning to implicate starch, such as that in refined grain products, as an important culprit in weight gain and diabetes.

A Little Math

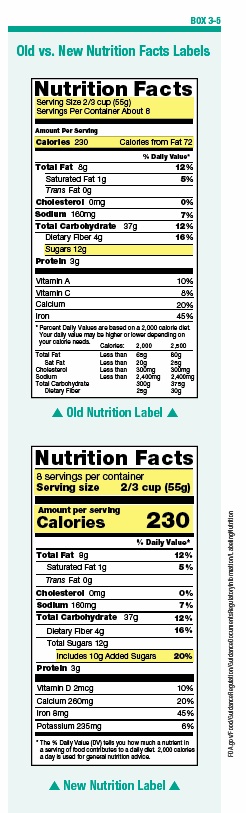

That breakdown—fiber, sugar, or starch—is probably the best tool to understand carbohydrates and how to make wise choices among different sources. You can quickly see the fiber and sugar content of foods on the Nutrition Facts panel, and recent revisions to the panel include a separate listing of added sugars (see “Old vs. New Nutrition Facts Labels, Box 3-5). To find the starch content takes just a bit of math: Subtract the fiber and sugar grams from the total grams of carbohydrates. To calculate the starch content of a one-cup serving of corn flakes, for example, subtract the fiber (1) and sugar (3) grams from the total carbohydrates (24): 24-1-3=20 grams of starch (about the same amount as in a cup of potatoes).

The American Heart Association advises using the ratio of total carbohydrates to fiber as a quick gauge of a food’s carbohydrate quality, with a target of no more than 10 grams of carbohydrates per 1 gram of fiber. In our corn flakes example, the carb-to-fiber ratio would be 24:1, more than double the recommended 10:1. By comparison, a bowl of whole-grain fiber cereal contains 25 grams of total carbs, 14 grams of fiber and 0 grams of sugars, for a net starch content of just 11 grams (25-14-0) and a ratio of 1.8:1.

Simple or Complex

In a distinction that confuses many people, carbohydrates are also classified as simple or complex. Simple carbohydrates are made up of one (single) or two (double) sugar molecules. When most people think of simple carbohydrates, they think of sucrose (a double sugar), the stuff you sprinkle on cereal or spoon into your coffee. But that’s only the most familiar simple carbohydrate. Others include glucose (a single sugar found in most fruits), fructose (a single sugar also found in fruits), galactose (a single sugar found in dairy products), lactose (a double sugar found in dairy products), and maltose (found in certain vegetables and in beer).

The nutritional value of simple carbohydrates depends on the foods in which they are found—they are not necessarily bad for you or to be avoided. Simple sugars such as those found in candy, non-diet sodas, syrups, and table sugar provide calories, but few other nutrients. In contrast, intake of nutritious foods such as fruits, vegetables, milk, and other dairy products provides not only calories from sugar, but also essential vitamins and minerals. This distinction is similar to that seen in warnings about “added sugar.”

Starchy Choices

Carbohydrates that have three or more sugars are called complex. These “starchy” carbohydrates are found in foods including beans and other legumes, starchy vegetables (corn, potatoes), and whole-grain breads and cereals. The health impact of complex carbohydrates, again, depends on what else they bring to the table. Legumes, vegetables and whole grains provide essential nutrients; on the other hand, refined complex carbohydrates, such as white flour, are stripped of many of their original nutrients in processing.

As noted above, moreover, the healthy halo associated with complex carbohydrates has been tarnished by recent research linking starchy foods to weight gain and diabetes (both of which are bad for your brain). In findings recently published in PLOS Medicine, intakes of starchy vegetables such as corn, peas, and potatoes were each associated with more weight gain.

What About the Glycemic Index?

One reason starchy foods might contribute to weight gain and diabetes risk is that they tend to have a higher glycemic index (GI), a measure of how quickly your body converts a food to glucose. Low-GI foods are slowly digested and include lentils, soybeans, and many whole grains. In contrast, high-GI foods are converted to glucose more rapidly; these include potatoes and white bread.

When a food’s typical serving size is factored along with its glycemic index, the result is called the glycemic load. Choosing lower-glycemic foods is generally associated with health benefits, including possible reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, though recent research has questioned the cardiovascular benefits of low-GI eating.

The evidence for brain benefits of a low-GI diet is also inconsistent. Some studies have shown benefits, while others failed to find any differences, and still other studies showed effects on only some aspects of cognitive performance.

The Bottom Line on Carbs

You can be forgiven if at this point you find yourself a little confused about carbohydrates and your brain. As we’ve seen with fats, carbohydrates are neither all good nor all bad. Tufts researchers have even found that very low-carbohydrate diets could have a negative impact on thinking and cognition. That’s likely because the brain doesn’t store glucose, its primary fuel, but depends on the body’s production of it from carbohydrates in the diet. After only a day or two, even the glucose stored by the body is exhausted and must be replenished by food.

Other research has connected consumption of certain kinds of carbohydrates to possible brain benefits. Scientists at Utah State University and Duke University reported results from an 11-year assessment of diet and cognitive function among 3,831 men and women, ages 65 and up. Their findings showed that higher adherence to both the DASH plan and the Mediterranean diet corresponded with better cognitive ability. In particular, however, the researchers wrote, “Whole grains and nuts and legumes were positively associated with higher cognitive functions and may be core neuroprotective foods common to various healthy plant-centered diets around the globe.” (See Box 3-6, “What Are Whole Grains?”)

Don’t Overdo It

On the other hand, consuming too many carbohydrates relative to protein and fat seems to contribute to cognitive decline. In one study, scientists reported that people 70 and older who ate the highest proportion of carbohydrates were at nearly four times the risk of developing mild cognitive impairment than their counterparts who ate relatively fewer carbohydrates. Risk also rose with a diet heavy in sugar. Study participants who consumed more protein and fat relative to carbohydrates were less likely to become cognitively impaired.

Do You Need More Protein?

The latest dietary fad to hit supermarket shelves is the booming popularity of protein, in everything from breakfast cereals to the so-called “Paleo” diet. In fact, however, most Americans probably already get plenty of protein—and too many of the calories and saturated fats that accompany animal sources of protein. The Daily Value (DV) used on Nutrition Facts panel percentages is 50 grams. Most of us far exceed that number, with actual consumption estimated at 62 to 66 grams of protein daily for women and 88 to 92 grams for men (see Box 3-7, “Your Protein Plan”).

The story may be different for older people, however. “It’s estimated that 20 percent of people between the ages of 51 and 70 have an inadequate protein intake,” says Paul Jacques, DSc, director of Tufts’ HNRCA Nutritional Epidemiology Program. Often, older people simply eat less as appetites wane, and that means consuming less protein.

Recent research by Dr. Jacques and colleagues, in fact, found that to get the most out of exercise, older participants also had to be consuming enough protein. Participants who did muscle-strengthening exercises without protein intake of at least 70 grams daily actually had lower muscle mass.

Base Intake on Body Weight

How much protein you need really depends on your body weight—0.8 grams of protein per 2.2 pounds. For example, a 125-pound woman would need 46 grams of protein per day, while a 175-pound man would need 64 grams per day. If you are very physically active, you may need to increase that. You might also want to spread your protein consumption through the day, rather than concentrating it at dinnertime (see Box 3-8, “Timing Your Protein”).

As you age, protein is essential to prevent the loss of lean muscle mass, called “sarcopenia,” and for the brain. Protein is important to your brain for the production of neurotransmitters and enzymes, and to maintain the structural components of the brain.

So you should aim to consume enough protein from lean, healthy sources to keep your muscles and brain strong, while avoiding the extra calories and saturated fats that accompany less-healthy protein sources.

The changing recommendations of how best to balance fats, carbohydrates, and proteins in a brain-healthy diet can seem like a roller coaster. But that “roller coaster” is best understood as not a circular ride at all, but an occasionally winding journey. As science uncovers new evidence, naturally, those dietary recommendations will detour to match. That’s the nature of science and discovery—otherwise, our maps would still show where “there be dragons.”

As science continues that journey, the best advice for eating to promote a healthy brain is to avoid fad diets, quick fixes, and radical swings to extremes. In short, use your brain—in the form of common sense—to eat right to protect it.

The post 3. Fats, Carbohydrates, and Protein appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 3. Fats, Carbohydrates, and Protein »

Powered by WPeMatico