4. Can You Reduce Your Risk for Dementia?

While we’re waiting for scientists to locate just the right drugs to treat or prevent Alzheimer’s disease, there are positive and active steps everyone can take right now. One message from research is that exercise, a healthy diet, mental stimulation, and social interaction may help preserve brain function longer. Because Alzheimer’s disease probably starts long before symptoms appear, it’s important to get started early to develop the types of healthy habits that can keep your mind sharp as you age.

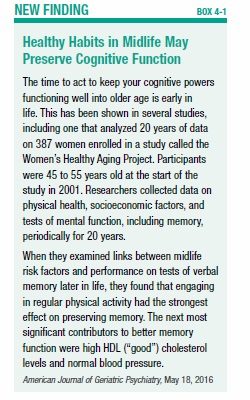

It’s likely that a combination of healthy habits is the key. One study found that a comprehensive program of exercise, social activities, nutritional counseling, and cognitive training, along with management of heart disease risk factors (including high blood pressure and high cholesterol), resulted in better performance on tests of memory and other mental functions. A recent study found that regular exercise, high HDL cholesterol levels, and normal blood pressure in middle age were linked to better performance on memory tests 20 years later (see Box 4-1, “Healthy Habits in Midlife May Preserve Cognitive Function”).

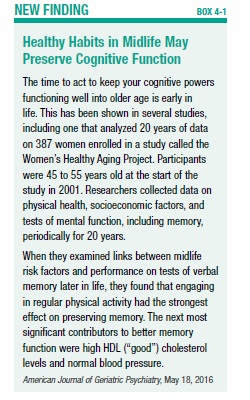

Whether a healthy lifestyle can actually prevent Alzheimer’s disease has not been proven. It may help maintain a healthy brain in people without dementia, and it could forestall the onset of the disease for a few extra years. There’s no debate about the benefits of exercise, weight control, and healthy eating for overall good health. A list of steps for maintaining a healthy heart and possibly a healthy brain appears in Box 4-2, “Steps That May Reduce Your Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease,” on page 30.

Food for Thought

Several studies have shown that eating a healthy diet might help lower your chances of getting Alzheimer’s disease. Some studies single out particular foods or nutrients, like omega-3 fatty acids, individual vitamins, or leafy green vegetables, while others examine the effects of an overall eating pattern, like the Mediterranean diet.

Mediterranean, DASH, and MIND Diets

Evidence is mounting that adopting a “Mediterranean-style” diet, or something similar, may have some protective effect on mental function. This diet emphasizes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, potatoes, beans, and nuts and seeds. Olive oil is an important source of monounsaturated fat. Dairy products, fish, and poultry are consumed in low to moderate amounts. Little red meat is eaten. Eggs are consumed zero to four times a week. Wine is allowed in low to moderate amounts.

One study of more than 17,000 people found that those who most closely adhered to this type of diet were 19 percent less likely to have impaired mental function. Another study found that people who consumed even more olive oil and nuts than recommended in the standard Mediterranean diet had better memory and thinking abilities than people simply advised to eat a low-fat diet.

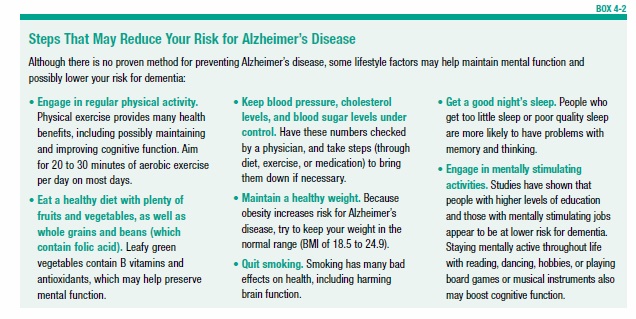

Another group of researchers looked specifically at whether diet might reduce risk for Alzheimer’s disease. They analyzed food questionnaires filled out by 923 people ages 58 to 98 who were followed for four to five years. Some participants followed a Mediterranean diet and some followed the heart-healthy DASH diet. Others conformed to a diet that is a hybrid of these two diets and called the MIND diet. It emphasizes vegetables, particularly leafy green ones (like kale and spinach), berries (specifically blueberries), whole grains, beans, poultry, and fish (see Box 4-3, “What’s in the MIND Diet?”). The diet allows for small amounts of red meat and butter. The researchers found that study participants who strictly adhered to all three diets had a lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease compared to those who did not follow the diets. Those who strictly followed the MIND diet had a 53 percent lower risk, and those who only stuck to it moderately reduced their risk 35 percent.

Key ingredients of these diets are the vegetables, particularly green, leafy ones, and berries. In one study, people who ate at least 2.8 servings of vegetables a day had a 40 percent slower rate of cognitive decline than those who ate less than one serving per day. Eating green, leafy vegetables produced the slowest rate of decline. The reason for the positive effect of vegetables on mental function may relate to the fact that vegetables contain vitamins such as E, B6, and B12.

The MIND diet also emphasizes blueberries, which contain certain antioxidants and flavonoids that have been shown to have strong potential to protect brain function. In a recent small study, 47 people with mild cognitive impairment who consumed freeze-dried blueberry powder were found to have an improvement in cognitive function (see Box 4-4, “Blueberries May Slow Mental Decline”). That said, there have been many foods associated with risk reduction which, on more rigorous testing did not show significant benefit.

Fish as Brain Food

Evidence showing that omega-3 fatty acids benefit brain function comes from studies in both humans and mice. Omega-3 fatty acids are found in fish such as salmon, tuna, herring, and sardines. Several epidemiologic studies have found a connection between consuming fish one or more times per week and reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, compared to people who rarely or never eat fish.

Studies in mice also show a benefit for omega-3 fatty acids. One study was conducted in specialized laboratory mice that were genetically engineered to develop the brain abnormalities of Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers tested the effects of one omega-3 fatty acid, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Mice fed a diet high in DHA performed better on a memory test and had less damage to their brains than mice fed a diet deficient in DHA. A clinical trial now underway with researchers in Oregon is seeking to determine whether an omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) therapy can promote brain health by supporting the small blood vessels in the brain in older adults at high risk for cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s. Results are expected by 2020.

Alcohol

Red wine may offer some benefit, but be careful not to overdo it. Studies have found that moderate alcohol consumption (mostly in the form of red wine) may have a moderate effect on reducing risk for Alzheimer’s disease. The mechanism by which alcohol might protect the brain is not known. Excessive drinking is certainly not recommended because it may increase the risk for damage to the brain. Some studies have found that heavy drinking increases the risk for cognitive impairment. In addition, drinking alcohol while taking certain medications can be harmful.

Do B Vitamins Help?

It has long been known that a vitamin B12 deficiency can cause a form of dementia that differs from Alzheimer’s disease. If caught early and treated with vitamin B12 supplementation, this type of dementia is reversible.

The B vitamins (B6, B12, and folic acid) may also have a role in Alzheimer’s disease. This is related to their effect on homocysteine, an amino acid (the building blocks of proteins) that is present in the blood. High levels of homocysteine have been associated with a higher risk for heart disease, stroke, and Alzheimer’s disease. The B vitamins help to break down homocysteine, and a lack of these vitamins allows homocysteine to build up in the bloodstream.

For this reason, it is important to obtain at least the minimum recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of B vitamins to prevent a deficiency. The importance of these vitamins on mental function is supported by several studies.

Vitamins B6 and B12 are found in animal products, while folic acid is contained in leafy green vegetables, orange juice, and fortified breads and cereals.

Because some older adults don’t secrete enough gastric acid to properly absorb vitamin B12 from food, taking a B12 supplement is a safe and simple strategy to ensure that your body is receiving adequate amounts of this important nutrient. Additionally, older adults should consider having an annual blood test as part of a routine physical examination to check for B12 deficiency.

Should You Take Vitamin E?

Antioxidant vitamins (C, E, and beta-carotene) help eliminate free radicals—highly reactive molecules that can damage cells in the brain and elsewhere in the body. Because there is evidence of free radical damage in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients, it is theorized that these antioxidant vitamins can offer protection against Alzheimer’s. In particular, vitamin E has been thought to lower the risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Several studies have looked at whether any of these vitamins protect against Alzheimer’s disease, with conflicting findings. One study found that people who obtained high amounts of vitamin E from the food they ate were less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease compared to people who consumed the lowest amounts of vitamin E. The same was not found to be true for the other antioxidant vitamins.

One study found that people who took supplements containing a combination of 400 International Units (IU) of vitamin E and 500 milligrams (mg) of vitamin C had a reduced risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Another study looked at the intake of vitamins C, E, and beta-carotene in both food and as supplements. This study found that none of them reduced the risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Many common foods contain antioxidants, so eating a well-balanced diet can help ensure that you are getting at least the RDA of these vitamins. Vitamin C is found in citrus fruits, tomatoes, red and green bell peppers, broccoli, strawberries, cabbage, spinach, and collard greens. The RDA of vitamin C is 75 mg per day for women and 90 mg for men.

Vitamin E can be obtained from soybean, corn, cottonseed, and safflower oils. Nuts, seeds, and wheat germ are also good sources, as are leafy green vegetables. The RDA for vitamin E is 22 IU.

Beta-carotene can be found in carrots, sweet potatoes, cantaloupe, and other fruits and vegetables that are a deep red, orange, or yellow color. Some dark-green vegetables, such as broccoli, kale, and spinach, also contain beta-carotene.

The question is, does it make sense to take supplements with quantities of these vitamins (particularly vitamin E) that far surpass the RDA? The answer is not currently known.

Some doctors recommend that their patients take a daily supplement of up to 200 to 400 IU of vitamin E. However, because vitamin E thins the blood, high doses (more than 2,000 IU) can be dangerous. Anyone on medications, particularly the blood-thinning drug warfarin (Coumadin), should consult with their doctor before taking a vitamin E supplement.

In addition, one meta-analysis of a number of studies has found that doses of vitamin E exceeding 400 IU may slightly increase your risk of dying. Although the increased risk was very small, it’s best to ask your doctor before routinely taking more than 400 IU of vitamin E per day.

A Dose of Sunshine: Vitamin D

Vitamin D, which is necessary for bone health, has many other essential functions throughout the body, including the brain. Low levels of vitamin of D have been linked to cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults in a number of studies, including a recent one (see Box 4-5, “Low Vitamin D Levels Linked to Signs of Dementia”). It would seem to follow then that increasing vitamin D levels with supplements would improve mental function. But, this has not yet been demonstrated in clinical studies.

Even though evidence is lacking for a clear cognitive benefit from taking vitamin D supplements, everyone should get at least the RDA of this vitamin. It’s vital for bone health, and it may have other benefits, including for the brain. Adults up to age 70 should get 600 IU of vitamin D per day. After age 70, the RDA goes up to 800 IU.

The primary source of vitamin D is the sun. A substance in skin reacts to the ultraviolet B rays of the sun, turning it into the form of vitamin D the body can use. Fifteen to 20 minutes of exposure (without sunscreen) a day should provide enough. But many people don’t get this much because they use sunscreen, wear clothes that cover most of their body, or don’t spend enough time outdoors. People who live in northern parts of the United States may need more exposure time because the angle of the sun limits the UVB rays.

Very few foods naturally contain vitamin D. They include cod liver oil, salmon, and other fatty fish. Some foods, like milk and breakfast cereal, are fortified with vitamin D.

A simple blood test can determine whether vitamin D levels are adequate. If the level is too low, vitamin D supplements can be taken.

Benefits of Physical Activity

Several large, well-designed studies have concluded that exercise is good for the brain. Even moderate exercise, such as walking, when done regularly, has proven benefits for mental function. The evidence is convincing that regular physical activity (walking, bicycling, swimming) improves mental function. A few studies also suggest that it may reduce the risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Exercise Boosts Mental Function

Here’s some of the evidence for improved mental function: A study of 124 previously sedentary adults (ages 60 to 75) compared the effects of aerobic exercise (walking) to anaerobic exercise (stretching) on different aspects of mental function, such as memory and executive processes (such as planning and scheduling). Participants who engaged in a regular aerobic exercise program showed significant improvement in performing mental tasks, while those in the other group did not.

The Nurses’ Health Study has been collecting data on thousands of female nurses for more than three decades. In part of this study, researchers analyzed data on more than 18,000 women, ages 70 to 81, to determine how physical activity affects mental function. Women who were the most physically active scored highest on tests of mental performance; they had a 20 percent lower risk of mental impairment than women who were the least active. In this study, physical activity did not have to be strenuous. Women who walked at a leisurely pace for at least six hours per week had improved mental function. Even women who walked for just two to three hours per week did better on tests of cognition than sedentary women.

Exercise May Reduce Risk for Dementia

Some evidence shows that regular exercise may do more than improve current mental function. It may prevent or at least delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment. In the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study, researchers looked at the relationship of physical activity (specifically walking) to dementia in 2,257 men, ages 71 to 93. Men who walked less than one-quarter mile each day had almost twice the risk of developing dementia as men who walked more than two miles each day.

One study found that people who have the ApoE4 gene (which increases risk for Alzheimer’s disease) and engage in regular physical activity had no shrinkage in the hippocampus (a brain region responsible for memory that is affected by Alzheimer’s disease) compared with a three percent smaller size of that brain region in their sedentary counterparts.

A recent study looking at the effects of aerobic exercise on the brain found that in people who engaged in a variety of physical activities several brain regions were larger than in people who did not exercise (see Box 4-6, “Aerobic Physical Activity May Preserve Brain Volume”).

Another study found that physical exercise in middle age and later in life may decrease risk for mild cognitive impairment—a condition that can lead to dementia in some people.

Physical activity has been shown to lower risk for stroke, heart disease, and diabetes, all of which can have a detrimental effect on memory. Preventing these conditions may also help to stave off dementia.

You don’t have to become a marathon runner to achieve the benefits, but some form of regular physical activity is important. Try to get 20 to 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise on most days. This can be a brisk walk or some other type of exercise that you enjoy. Even greater health benefits can be gained from more vigorous activity for longer periods of time.

Education and Mental Stimulation

People with higher levels of education and those with mentally challenging jobs appear to be at lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. Many experts believe that education and mental stimulation don’t actually prevent dementia. Instead, they confer a benefit to the brain that allows the person to maintain normal mental function longer even as plaques and tangles and other damage are developing in the brain. This is called “cognitive reserve.”

People with more education and those with mentally challenging jobs are able to compensate longer for cognitive difficulties than those with less education. Thus, it may be that more highly educated people have a delay in the onset of the most mentally debilitating stage of the disease.

Education even at a young age may impact later risk for dementia. In one study, people with the lowest grades in childhood had a 21 percent increased risk for dementia later in life. Those who had occupations that required working with data and numbers had a 23 percent lower risk for dementia. The lowest risk (39 percent reduction) was seen in people who had both high grades in childhood and worked in mentally challenging jobs.

In another study, the risk for dementia was 50 percent higher for those with the lowest grades when they were 9 or 10 years old. Women whose occupations were complex and required them to work with people (negotiating, instructing, or supervising) had a 60 percent reduced risk for dementia.

Education and job complexity are clearly beneficial. But any mentally stimulating activity may help. Several studies have found that leisure time activities, such as reading, playing board games, playing musical instruments, dancing, knitting, and gardening, may help preserve memory and thinking abilities longer. A recent study found that people who used a computer, engaged in regular social activities, or read magazines were less likely to develop memory and thinking problems than people who did not do these things (see Box 4-7, “Social Engagement and Computer Use May Help Memory”).

Education, challenging work, and an engaged mind possibly protect brain function. But is there some specific type of brain training that will build cognitive reserve and keep dementia at bay for as long as possible? Researchers are looking into that. There is no definitive answer. But one study has produced some intriguing findings (see Box 4-8, “Brain Training May Protect Brain Function,” on page 37). In this study, use of a computer program that improves the speed at which the brain processes information appeared to reduce risk for dementia. With this program, the user identifies an object (such as a truck) at the center of his or her gaze while at the same time identifying a target in the periphery (such as a car). As the user gets the answers correct, the speed of presentation becomes progressively briefer, while the targets become more similar. This was an encouraging finding, but it must be replicated in other studies to say with any confidence that it can actually affect the incidence of dementia.

Social Support

Intellectual stimulation alone may not be enough. Keeping the brain active with social activities also may help you stay sharp longer, according to several studies. In a study of 800 men and women age 75 and older, researchers found that leisure activities combining social, mental, and physical activity helped protect mental functioning over the long term. Those who engaged in the most mental, physical, and social activities had a lower risk for developing dementia, and the greatest effect was among people who engaged in all such activities.

One study found that people who are both socially active and not easily stressed have a lower likelihood of developing dementia. Loneliness may have the opposite effect. A study found that being lonely may accelerate decline in memory and thinking. And having a greater purpose in life was found to reduce the risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Keep in Mind

Some caveats regarding research on physical, mental, and social activity must be noted. For example, cause-and-effect relationships between mental or physical exercise and reduced risk for Alzheimer’s disease are very difficult to prove. It may be that people who do not suffer from dementia are simply better able to engage in more complex mental tasks. People who later develop dementia may have a less-active social life because they are experiencing subtle early symptoms of the disease. And people with Alzheimer’s disease may simply exercise less than those without dementia. The early and subtle manifestations of the disease could impair a person’s motivation or ability to organize and follow through with an exercise plan.

It is possible that the difference in rates of Alzheimer’s disease between highly educated and less-educated people is actually linked to socioeconomic status. Less-educated individuals are likely to be in a lower socioeconomic group and have less access to medical care. Without adequate healthcare, they are more likely to have untreated high blood pressure, diabetes, and other conditions that have been shown to increase risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

No physical, mental, or social activity can guarantee protection against Alzheimer’s disease. Even people who stay intellectually engaged and physically active into older age can succumb to the disease. On the other hand, there’s no harm in reading books, doing crossword puzzles, dancing, walking, visiting friends, and engaging in hobbies. And these activities can be very enjoyable and lead to a higher quality of life.

The post 4. Can You Reduce Your Risk for Dementia? appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 4. Can You Reduce Your Risk for Dementia? »

Powered by WPeMatico