5. Diagnosis

No one test will prove that a person has Alzheimer’s disease. However, a skilled physician can conduct a comprehensive evaluation and make the diagnosis with more than 90 percent accuracy.

Alzheimer’s disease actually starts to develop before symptoms become apparent. The plaques and tangles most likely exist within the brain for years until they eventually cause enough damage for changes in memory and mental function to become noticeable. Because the brain begins changing before behavior does, it’s important to look for signs of the disease early. Some drugs are effective in improving mental function in the mild-to-moderate stages of the disease. However, early detection can be difficult because the onset of the disease is usually subtle, and the cognitive changes can vary from person to person.

Early Warning Signs

Many people fear that everyday acts of forgetfulness, such as not remembering where you put your car keys, are early signs of Alzheimer’s disease. Although forgetfulness can be an early warning sign of Alzheimer’s, the memory loss of Alzheimer’s disease is more serious than normal age-related memory difficulties. Misplacing your keys only to find them later is not uncommon. Placing the keys in an odd or inappropriate location, such as inside the sugar bowl, and completely forgetting about it indicates a more serious problem.

With Alzheimer’s disease, forgetfulness is a consistent problem, and the information generally is not recalled later, as it often is with normal aging. Also, Alzheimer’s disease affects more than just memory. Language, behavior, and the ability to handle day-to-day tasks also become compromised.

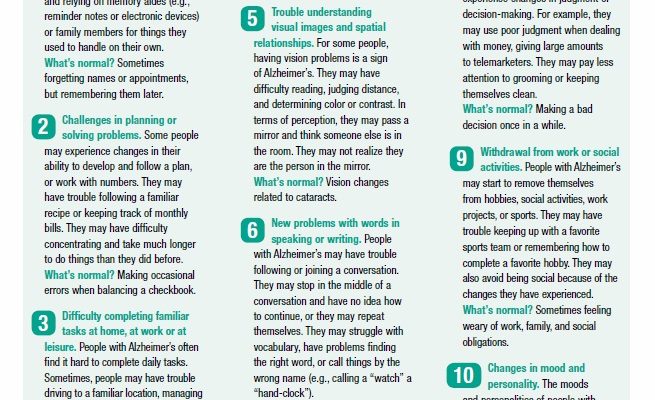

To help recognize the warning signs of Alzheimer’s disease, and to distinguish them from normal memory lapses, the Alzheimer’s Association has developed a checklist of common symptoms. These are listed in Box 5-1, “10 Warning Signs of Alzheimer’s Disease,” on page 40.

Alzheimer’s disease begins with mild symptoms and gets worse over time. For most people, memory problems will surface first. Difficulty with other cognitive functions, such as language and judgment, will also occur. Some people are aware of the cognitive decline, while others are not. In many cases, relatives and friends first notice a problem. If you suspect that you or a loved one has cognitive impairment, see a physician. A primary care physician may refer you to a neurologist or psychiatrist for evaluation. You also may see a neuropsychologist for additional tests.

Diagnostic Evaluation

No single comprehensive diagnostic test detects Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers are, however, making great progress in developing new techniques that may enable physicians to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease at an early stage, but many of these technologies are not yet ready for routine use.

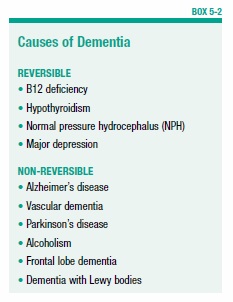

With tests available today, it is almost always possible to diagnose dementia. But it may be more difficult to identify the type of dementia. Therefore, a thorough diagnostic examination is important because other problems, aside from Alzheimer’s disease, may cause dementia. Other possible causes of dementia include stroke, vitamin B12 deficiency, hypothyroidism, normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), certain medications, Parkinson’s disease, depression, and other illnesses (see Box 5-2, “Causes of Dementia”).

With some of these conditions, such as B12 deficiency, hypothyroidism, and NPH, dementia is reversible with early treatment. If a medication is causing the problem, stopping the drug or changing the dosage often will correct the cognitive impairment.

The first step in the diagnostic evaluation is to conduct a thorough medical history, followed by physical, psychological, and neurological exams. Blood will be drawn to test for thyroid function and vitamin levels (specifically vitamin B12 and folate).

Brain Imaging

Brain imaging studies will most likely be included. The most common methods of imaging the brain are the computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Although certain findings on these scans may support a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, their primary purpose is to look for evidence of tumors, severe head trauma, or prior strokes. The detection of prior strokes doesn’t completely rule out Alzheimer’s disease. But it’s important to know whether strokes have caused cognitive impairment so you can take steps to prevent future strokes.

A CT scan also can help to distinguish NPH from Alzheimer’s disease. In NPH, an abnormal accumulation of fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord can cause cognitive impairment, gait problems, and urinary incontinence, all of which also may be features of Alzheimer’s disease, although in Alzheimer’s these are usually not the initial symptoms. The fluid accumulation can be seen on a CT scan. NPH is treated by draining the fluid, which reverses the symptoms in many people.

Tests of Mental Function

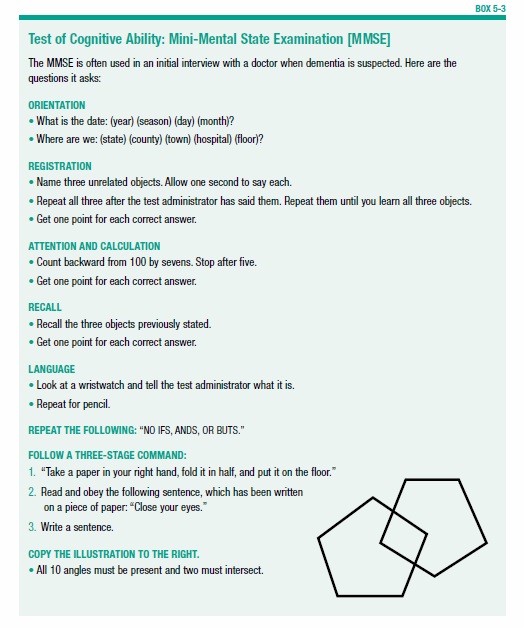

Important diagnostic information is further gleaned from tests of cognitive ability. These range from brief screening tests—often given by a doctor during the initial visit—to in-depth evaluations performed by a neuropsychologist. One commonly used short test is called the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), which is a series of questions that evaluate a person’s orientation, attention, language, and calculation ability (see Box 5-3, “Test of Cognitive Ability: Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE],” on page 43). This test, which can be performed in about eight minutes, is helpful, but it has some limitations. Patients with mild-stage Alzheimer’s disease who are highly educated may get a perfect score, while people with minimal education or who are not questioned in their primary language may get a low score even though they don’t have dementia.

Another simple test that some physicians use to determine if someone should have a more thorough evaluation is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). This test takes about 12 minutes and includes assessment of some mental functions that are not part of the MMSE.

If the quick screening tests done by a physician show problems with memory and thinking, more comprehensive tests of cognitive ability will be performed by a trained professional, such as a neuropsychologist.

Making the Diagnosis

Once all other forms of dementia have been ruled out, a doctor will make a diagnosis of “probable” Alzheimer’s disease. At this point, the patient and family need to consider appropriate care plans, safety measures, and treatment options.

This is also a good time to join a support group or to otherwise seek help with the psychological impact of receiving the diagnosis. A physician can make the diagnosis, but he or she may not have the resources to help the patient and family cope with the situation they now face. Support groups are available for both people with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers. The Alzheimer’s Association is a good source for finding these groups (see Appendix II: Resources, page 96).

Diagnostic Criteria

For many years Alzheimer’s disease was considered to begin around the time a diagnosis was made using the methods described above. However, it is known that the disease process actually begins before the diagnosis can be made. Researchers now believe that effective treatments for Alzheimer’s disease will most likely be effective only if given very early in the course of the disease.

For all of the pieces to come together, the diagnosis must be made and treatments given before symptoms appear. This is not yet possible, but the hope is that it will be in the near future. New tests that use imaging studies and blood and other tests have shown great promise for early detection. These are described in greater detail in Chapter 11.

To reflect the deeper understanding of Alzheimer’s disease and to prepare for future advancements in diagnosis and treatment, the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association revised the diagnostic guidelines. The updated guidelines cover the full spectrum of the disease as it gradually changes over many years. They describe three distinct stages of Alzheimer’s disease: the earliest preclinical stage (before symptoms appear), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease.

- Preclinical: In this stage, brain changes have begun but symptoms are not evident. In some people, buildup of beta-amyloid in the brain can be detected with new, experimental tests. These are used only in research settings. Currently, this stage is used only in the context of a research study, and the diagnostic parameters are still being evaluated.

- MCI: The MCI stage is marked by symptoms of memory problems, enough to be noticed and measured, but not compromising a person’s independence. People with MCI may or may not develop Alzheimer’s dementia. For now, the guidelines for the MCI stage are also largely for research purposes.

- Alzheimer’s Dementia: These criteria apply to the stage of the disease when symptoms are evident and causing problems.

The post 5. Diagnosis appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 5. Diagnosis »

Powered by WPeMatico