3. Who is at Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease?

A good deal of research has been done to try to pinpoint who is at greatest risk for getting Alzheimer’s disease. Simply getting older raises your risk, but age alone does not mean a slow decline toward dementia. Beyond age, there are certain factors that may further increase risk. Most likely, several factors interact to set off the chain of events that cause Alzheimer’s disease. The process likely begins at a younger age than previously thought. This highlights the need to start taking actions to reduce risk early in life.

Certain risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease cannot be altered, such as age and genetics. Other risk factors relate to medical conditions, such as diabetes, cholesterol levels, and depression. Several other potential risk factors have been studied, some of which may play a role.

Risk Factors That Cannot Be Changed

Age

The most important risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease is advancing age. While simply getting older doesn’t cause the disease, the risk for Alzheimer’s disease steadily rises over time beyond the 60s. People over age 85, the fastest growing demographic in the United States, are at the highest risk.

Genetics

If a parent, brother, or sister had Alzheimer’s disease, does this mean you should worry that you might get it too? This is not an easy question to answer because of the complex genetic basis of the disease. If a parent or sibling had Alzheimer’s disease, your chances of also getting the disease are higher. This is because you may have inherited genes that make you more susceptible to the disease. In rare cases, people inherit genes that don’t just make the disease more likely, they ensure that the person will get it. This genetically determined Alzheimer’s disease accounts for just one percent of all people with the disease.

Genetically Determined Alzheimer’s Disease

In people with genetically determined Alzheimer’s disease, defects exist in one or more of three genes. People with even one of these genetic defects will develop Alzheimer’s disease (usually between ages 30 and 60), and they have a 50 percent chance of passing the gene mutation on to their children.

One of the defective genes causes the production of an abnormal amyloid precursor protein (APP). The APP protein breaks down into a destructive amyloid protein, beta-amyloid. As explained in Chapter 1, amyloid protein forms plaques in the brain, and may be the trigger event of Alzheimer’s disease. The two other genes that, when they have mutations, have been connected to early-onset Alzheimer’s disease produce proteins called presenilin 1 and presenilin 2. These proteins appear to be involved in the breakdown of APP into beta-amyloid.

Another apparent direct genetic link to Alzheimer’s disease occurs in people with Down syndrome, who have three copies of chromosome 21. The APP gene is located on chromosome 21. Due to cognitive impairment caused by Down syndrome, it can be difficult to evaluate these people for Alzheimer’s disease. However, autopsy studies show that the brains of people with Down syndrome all have the plaques and tangles of Alzheimer’s disease as they age. Despite the presence of these physical manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease, the age of onset of cognitive decline varies, and not all adults with Down syndrome develop dementia.

Genes That Increase Risk

For most people with Alzheimer’s disease no one specific gene caused it. However, genetics probably does play some role. Research has shown that people with a parent, brother, or sister with Alzheimer’s are more likely to get the disease. People with two affected parents appear to have an even greater risk.

One likely genetic culprit appears to be a gene that codes for a protein called apolipoprotein E, which has different subtypes (alleles), called E2, E3, and E4. Everyone inherits two of these subtypes, one from each parent. Having the apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4) allele increases the risk for Alzheimer’s disease. But this is where the situation becomes complicated. Simply having a gene for ApoE4 does not necessarily translate into developing Alzheimer’s disease. Rather, it makes a person more susceptible than someone without the allele.

Some research shows that another apolipoprotein E allele, ApoE2, may actually decrease the risk for Alzheimer’s disease. About 10 to 20 percent of people in the United States have one or two copies of ApoE2. ApoE3 is the most common form, and it appears to have no impact on the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

ApoE4

Apolipoprotein E is a protein involved in the breakdown of lipids (fats) in the body, and it plays a role in heart disease. It is not clear what role it plays in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. However, about 46 percent of people with Alzheimer’s disease carry the ApoE4 gene, while it is present in just 14 percent of the general population. People with two genes for ApoE4 (one from each parent) are at greatest risk for the disease, but even people with only one gene for ApoE4 (from only one parent) have an increased risk. One study found that women who carry the ApoE4 gene may be more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than men who carry the gene.

It is possible to get tested for the presence of ApoE4. However, the test is not recommended because many people who carry the ApoE4 gene will never develop Alzheimer’s disease, and some who do not have this risk factor will develop the disease.

Scientists have identified several other genes, in addition to ApoE4, that appear to increase the risk for Alzheimer’s disease. A few genes have been discovered that protect against the disease. It is hoped that by identifying these genes researchers can gain insight into the causes of Alzheimer’s disease and possibly use that knowledge to develop more effective treatments.

Race

Several studies have examined whether race and ethnicity play any role in risk for Alzheimer’s disease. While findings differ among studies, it appears that African-Americans are about twice as likely as whites to develop Alzheimer’s disease. Hispanics have about one-and-a-half times the risk. There are several possible reasons for the differences. For example, conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure, which may increase risk for Alzheimer’s disease, are more common in African-Americans and Hispanics than in whites.

Other factors that may account for the difference relate to socioeconomic characteristics. Some conditions that have been linked to higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease are low level of education, low income, and living in a rural area as a child. In the United States, African-Americans and Hispanics are more likely than whites to have fewer than 12 years of education and to have low income. Why these socioeconomic conditions would be linked to Alzheimer’s disease is not completely understood.

There may be other explanations for the disparity among races, but these haven’t yet been discovered.

Other Possible Risk Factors

Research over the past several years has consistently found that certain health conditions and other factors (like smoking) increase a person’s risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease. In particular, some of the same conditions that make a person more susceptible to heart disease also make dementia more likely. The evidence is strongest for diabetes, high cholesterol, depression, and smoking. Other heart disease risk factors, such as high blood pressure and obesity, have been shown in some studies to increase the chances of getting Alzheimer’s disease.

Several studies have shown that the risk from these conditions starts rising when they are present in midlife. For example, in one study people in their early 40s who smoked or had high blood pressure, high cholesterol, or diabetes had a 20 to 40 percent increased risk of developing dementia in older age. People with all four risk factors had double the chance of developing dementia. One study found that treating high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes may lower the risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Further bolstering the evidence for a link between heart disease risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease is a study showing that people who had high cholesterol levels and diabetes prior to being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease experienced a faster decline in mental function once the disease was diagnosed.

In addition to these risk factors, suffering a moderate or severe head injury increases the risk for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Some evidence suggests that anemia, a condition in which the number of red blood cells is lower than normal, may also be linked to an increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Diabetes

Studies have found that people with type 2 diabetes are about twice as likely to develop vascular dementia or Alzheimer’s disease as people without diabetes. At least one study found that people with type 1 diabetes, which often begins in childhood, also have a greater chance of getting dementia.

Diabetes is a growing problem in the United States and it particularly affects older adults; 11.8 million people over age 65 (26 percent of people in that age group) have diabetes. Most of these people have type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes is a disease in which the body does not produce or does not properly use insulin. Glucose (a sugar used by the body as a source of energy) is one of the end products of food digestion. Insulin (produced in the pancreas) helps the body to absorb glucose into cells. All organs of the body, including the brain, need glucose to function. But insulin and glucose must be maintained in proper balance in the bloodstream.

In people with type 1 diabetes, the body fails to make insulin. The more common form of diabetes, type 2, is often caused by insulin resistance. This means that the body is producing insulin but is resistant to its effects. In both types of diabetes, the result is too much glucose in the blood. This condition, called hyperglycemia, has numerous detrimental effects, including raising the chance for decline in mental function.

Type 2 diabetes does not occur suddenly. Instead, over time the body becomes more and more resistant to insulin. When blood sugar levels reach a particular threshold, diabetes is diagnosed. Research shows that people with blood sugar levels that are higher than normal but not high enough to receive a diagnosis of diabetes (called prediabetes) perform worse on tests of memory and may be at increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. This was shown in a study of people who had a parent with Alzheimer’s disease or the gene that increases risk.

In addition to having an increased risk for dementia, older adults with diabetes face a higher risk of developing mild cognitive impairment, a condition that can be a precursor to Alzheimer’s disease. Thus, people with diabetes and mild cognitive impairment (see page 8) have an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Excess insulin may also be problematic. Some research suggests that both too much glucose and too much insulin in the blood can increase the amount of beta-amyloid (see page 12) in the brain.

Treatment

Treatment for diabetes is aimed at restoring the balance between insulin and glucose. People with type 1 diabetes must take daily insulin shots, while type 2 diabetes is often treated with diet, exercise, oral medications, and sometimes insulin shots. One study showed that people with poorly controlled diabetes—meaning the balance between insulin and glucose is not consistently maintained—are more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than people with diabetes that is well controlled. Another study found that older adults with type 2 diabetes who have had episodes of severe drops in blood sugar (hypoglycemia) have higher odds of developing dementia.

It’s hoped that the effective treatment of diabetes may reduce the risk of dementia. One study found that people with type 2 diabetes who used the diabetes drug metformin had a lower risk of developing dementia than people taking other commonly used diabetes drugs.

Prevention

The insulin resistance that occurs in people with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes is linked to obesity, a poor diet, and sedentary lifestyle. Healthier lifestyles can reduce insulin resistance. In fact, studies have shown that full-blown type 2 diabetes can be prevented in people with prediabetes who lose weight, eat a healthier diet, and increase physical activity.

High Cholesterol

High cholesterol is bad for the heart, and it also may harm the brain. Cholesterol is a fat-like substance that is made in the body and also contained in certain foods, like eggs and meat.

Cholesterol comes in more than one form. The “bad” low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol can build up in the walls of arteries and block blood flow. The “good” high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol helps clear excess cholesterol from arteries, thus slowing the dangerous build-up that can lead to heart attacks and strokes.

Research has found that higher levels of HDL cholesterol correlate with better mental functioning. HDL levels can be raised by increasing physical activity and eating foods containing monounsaturated fatty acids, such as olive oil.

When it comes to LDL cholesterol, try to keep levels low throughout life. Studies show that having high cholesterol levels in middle age increases risk for Alzheimer’s disease later on. Everyone should have their cholesterol levels checked at least every four to six years, and more often if levels are high or you have other risk factors for heart disease.

A total cholesterol level of less than 200 mg/dL is ideal. Eating a low-fat diet and getting plenty of exercise can help keep cholesterol levels under control. If those measures don’t work, drugs are available to lower LDL cholesterol.

Statins

Drugs used to lower the detrimental LDL cholesterol are called statins. Since high LDL cholesterol raises risk for Alzheimer’s disease it seems logical that lowering LDL levels with statin drugs would reduce risk—however, several studies looking into this have produced conflicting results. Some studies have been optimistic about the ability of statins to stall the onset of Alzheimer’s, while others found no protective effect against Alzheimer’s disease.

For now, the bottom line appears to be that having high cholesterol is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Lowering levels of LDL cholesterol while raising levels of HDL cholesterol, is desirable for heart health and likely for brain health, as well. However, it has not been proven that taking statin drugs lowers the risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Obesity

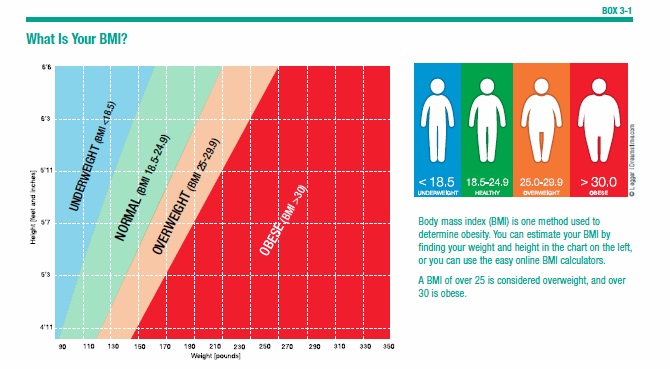

Obesity, a heart disease risk factor, has been shown to increase the risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease. Obesity is defined as having a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 (see Box 3-1, “What is your BMI?”). Numerous BMI calculators are available online, including one from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/lose_wt/BMI/bmicalc.htm). Studies have shown that obesity in midlife may raise the chances for dementia later in life. In addition, the location of the excess weight in the body may be as important as simply being overweight. One study found that people with a large belly in their 40s have increased risk for developing dementia in their 70s. Even those who were of normal weight but had large abdomens were at greater risk than those of normal weight with smaller waists. Obesity plus a large belly resulted in the highest risk, about 3.6 times greater than small-waisted people of normal weight.

One study presents an apparent paradox. It shows that while obesity in middle age increases risk for dementia, after age 65 being underweight has a stronger link to developing dementia than being overweight.

So far, researchers cannot explain the reason for the connection between obesity and dementia. One possibility is the fact that being overweight can lead to high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol, which all have been shown to contribute to the development of dementia. However, studies have found that being overweight or obese impacts the risk for Alzheimer’s disease aside from the presence of diabetes or heart disease. Something about excess body weight appears to trigger damaging brain changes that can lead to dementia.

Depression

About 20 percent of older adults suffer with depression. Signs of this emotional disorder are listed in Box 3-2, “Symptoms of Depression.” Several studies have concluded that depression increases the risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease. However, not all studies have found this link. In addition, there are several unanswered questions, such as whether it matters if depression is major or minor. Also, does it make a difference if depression occurs in early, middle, or late life? It appears from a few studies that depression in later life is most strongly related to increased risk for mental decline and Alzheimer’s disease.

Why would depression cause Alzheimer’s disease? For now, the answer to this question is not known. There may be a physiologic explanation. Alternatively, rather than triggering Alzheimer’s disease, depression may be an early symptom that precedes the memory and other cognitive impairments.

Changing Sleep Patterns

Several studies have shown a connection between getting too little or even too much sleep and cognitive impairment. One study of over 15,000 women age 70 and older found that those who slept five hours a day or less had lower scores on tests of cognition than those who slept seven hours a day. Those who slept nine hours a day or more also had lower cognition. Women whose sleep duration changed by two hours or more per day had worse cognition than those with no change in sleep duration.

Another study found that participants with sleep apnea or sleep-disordered breathing had more than twice the odds of developing mild cognitive impairment or dementia compared with those without these conditions. In addition, those who woke up more often during the night scored worse on tests of cognition and verbal fluency than those who slept through the night. One study found that mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease showed up at younger ages in people with sleep apnea. Among people who developed mild cognitive impairment, those with sleep apnea were diagnosed about 10 years earlier than those with normal sleep patterns. Among those who developed Alzheimer’s disease, it appeared five years earlier in people with disrupted breathing during sleep. On a positive note, treating sleep apnea delayed the decline in mental function.

The link between poor quality sleep and impaired cognitive function may be causative. In other words, inadequate sleep may lead to dysfunction in the brain that hinders memory and other mental function. But it also may be an early warning sign of dementia. This is not yet known. The connection between sleep and cognitive function continues to be studied.

It is known that getting enough good quality sleep is important for health, including cognitive health, at all ages. In today’s busy world, sleep deprivation is all too common. Sleep experts recommend that adults sleep seven to nine hours per night. But the amount of time spent snoozing is declining. On average, we get one to two hours less sleep per night than people did 50 to 100 years ago. An estimated 50 to 70 million Americans have some type of sleep disorder, such as sleep apnea, chronic insomnia, restless legs syndrome, and periodic limb movement disorder.

Sleep specialists recommend “sleep hygiene” techniques to help fall asleep and stay asleep for the recommended seven hours (see Box 3-3, “Sleep Hygiene”).

Head Injury

Some studies have suggested that having a head injury increases the risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease. The most common form of head injury is traumatic brain injury (TBI), which can result from a concussion caused by a motor vehicle accident, fall, sports-related injury, or other cause of injury to the head.

A TBI can be mild, moderate, or severe. A person with a mild TBI loses consciousness or has loss of memory of the event for less than 30 minutes. If this lasts for more than 30 minutes it is a moderate TBI. With a severe TBI this occurs for more than 24 hours.

Compared with people who have had no head injury, those who experienced a moderate TBI have twice the risk for dementia, and those who had a severe TBI have 4.5 times the risk. The increased risk has not been shown for mild TBI. One study found that older adults with mild cognitive impairment who reported having had a head injury in the past were more likely to have beta-amyloid plaques (a sign of Alzheimer’s disease) in their brains than those with no history of head trauma.

Soldiers in combat situations are susceptible to TBIs. In the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, for example, TBI accounted for 22 percent of all casualties and 59 percent of blast-related injuries. A study of veterans age 55 or older found that those who experienced a previous TBI were 60 percent more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease. In addition, among all veterans in the study who developed dementia, those who had a history of a TBI succumbed to the memory-robbing disorder two years earlier than those who never had a TBI (age 78.5 versus 80.7).

Attention has also been paid to some professional football players diagnosed with dementia at younger ages than would be expected. One study of the cause of death of almost 3,500 NFL players found that they were three to four times more likely to die from neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease) than the general public. Other studies suggest that cognitive impairment is more prevalent among former professional football players than the general public.

Do These Risk Factors Cause Alzheimer’s Disease?

It’s unlikely that conditions such as high cholesterol, high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, and smoking directly cause Alzheimer’s disease. Rather, they may set the stage for increased vulnerability.

The human body, including the brain, has mechanisms to protect itself from harm. But the detrimental effects of conditions such as high cholesterol may compromise these natural protective mechanisms. For example, the brain needs an adequate amount of blood to flow through its vessels, because blood is the source of the oxygen that nourishes the brain. If these vessels are clogged from the effects of high cholesterol or high blood pressure, the oxygen supply may be reduced, increasing the vulnerability of the brain.

Additionally, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, smoking, and diabetes increase risk for strokes. Many people with Alzheimer’s disease actually have mixed dementia, meaning they have both vascular dementia (as a result of prior strokes, for example) and the plaques and tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. Perhaps this explains the connection between stroke risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease. Or, maybe damage to the brain from strokes makes the brain more susceptible to developing the plaques and tangles of Alzheimer’s disease.

Researchers are still trying to untangle the interaction of risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease as they search for strategies to intervene early in the course of the disease (even before symptoms are noticed). For example, can disease risk be reduced by lowering blood pressure and cholesterol, and effectively treating diabetes?

The answer is not known. But it appears that keeping cholesterol and blood pressure low, eating a healthy diet, exercising, not smoking and keeping weight under control are good for the heart, as well as for the brain. This is especially important in early adulthood to middle age in order to preserve heart and brain function throughout life.

Cancer and Dementia

It appears that having cancer may actually lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Studies have found that people who’ve had cancer are less likely to get Alzheimer’s disease, and people who have Alzheimer’s disease are less likely to develop cancer.

A study that looked at health records of 3.5 million veterans showed that most types of cancer are associated with lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease and that chemotherapy treatment for most of the cancers lowered the risk even further. Survivors of liver cancer had the greatest reduction in risk for Alzheimer’s disease (51 percent). Other cancers associated with reduced risk were pancreatic cancer (44 percent), esophageal cancer (33 percent), myeloma (26 percent), lung cancer (25 percent), and leukemia (23 percent). Survivors of melanoma and prostate cancer also had decreased risk. Treatment with chemotherapy reduced Alzheimer’s risk by 20 to 45 percent (with the exception of prostate cancer).

So far, researchers cannot explain how cancer and cancer treatment affect brain cells in a way that potentially protects against Alzheimer’s disease. There may be other factors not related to cancer at work. Some researchers suggest another possible explanation for these figures. It may be that people who get cancer don’t live long enough to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

The post 3. Who is at Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease? appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 3. Who is at Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease? »

Powered by WPeMatico