5. Skin Conditions: Lyme Disease to Wrinkles

The skin conditions covered in this chapter begin with the increasingly common, tick bite-related Lyme disease and end with the fact-of-aging phenomenon called wrinkles. There are things you can do to prevent one and delay the other.

Many skin conditions involve some kind of lesion. A lesion simply means an abnormal growth or change in tissue, though the term is often associated with cancer. Most noncancerous skin lesions do not spread to other parts of the body, but benign lesions should nevertheless be self-monitored. If changes occur, have the lesion examined by a clinician. Look for new growth, moles that are increasing in size or color, and any growth that causes unusual itching, pain, or bleeding.

Some common skin growths may simply be unsightly (skin tags, for example), and many older adults prefer to seek medical attention to remove them. U.S. Pharmacist reminds us that because removal of benign skin growths are considered cosmetic, they may not be covered by Medicare or other health insurance plans. This means you have to decide between living with a skin tag or paying to have it removed.

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is caused by four kinds of bacteria and spread when people are bitten by a blacklegged deer tick. But not all  ticks carry the bacteria and not all people bitten by the tick get the disease.

ticks carry the bacteria and not all people bitten by the tick get the disease.

A characteristic feature of Lyme disease, and the key feature of early localized infection, is a slowly expanding red rash on the skin (called erythema migrans) at the site of the tick bite. The rash is often bull’s-eye shaped.

Poor sleep has emerged as a symptom of Lyme disease patients. A 2018 study published in the journal SLEEP found that people who have the condition report poor sleep quality before treatment and significantly worse sleep and sleep disturbance six months after treatment.

Contact your physician if you get a bulls-eye looking rash, flu-like symptoms, fever or chills, muscle or joint pain, headaches, fatigue, or weakness. Lyme disease is diagnosed by a physical exam and blood tests. If untreated, the disease can spread to the heart, joints, and nervous system.

Treatment with antibiotics is normally successful within a few weeks. If Lyme disease is detected later, antibiotics are still the treatment but it may take longer to get rid of the symptoms.

A person who has had Lyme disease once can get it again. There is no known vaccine, so reducing your exposure is the best way to prevent it.

Measles

In June 2019, the highest number of measles cases in the United States (1,123) was reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) since 1992. The condition had been reported in 23 states.

In June 2019, the highest number of measles cases in the United States (1,123) was reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) since 1992. The condition had been reported in 23 states.

The resurgence is due to misinformation about vaccines, the decline in vaccinated children, and foreign travel. Unvaccinated U.S. residents get the measles while they are abroad, bring the disease into the United States, and spread it to others.

The best way to protect against the disease is to get the measles-mumps-rubella shot (MMR). These three vaccines were combined in 1971. Rubella is also known as the German measles. The mumps is a contagious viral disease that attacks the salivary glands. Like the measles, mumps and rubella were common decades ago, but became rare due to the bundled vaccination program. If you were born prior to 1957, you were likely exposed to measles and have an adequate immune response. The CDC recommends that health-care workers, adults traveling overseas, college students, and anyone living near a community experiencing an outbreak get an MMR booster shot if they are unsure of their immunity. Another option is to get an inexpensive blood test (titer test), which can show if a you have enough measles antibodies to be protected against the disease. Claims that the MMR vaccine causes conditions such as autism and chronic diseases have long been scientifically discredited.

The CDC describes measles as a highly contagious viral respiratory illness that spreads through coughing and sneezing. It starts with a fever as high as 105 degrees Fahrenheit (°F), runny nose, cough, red eyes, and sore throat, and is followed by a rash that spreads over the body.

The rash usually appears about two weeks after exposure, and spreads from the head to the trunk and lower extremities. Those who get measles are contagious from four days before to four days after the rash appears. Some patients with compromised immune systems do not develop the rash. Those at high risk for complications are infants and children, adults over the age of 20, pregnant women, and those with impaired immune systems.

Very Contagious

Measles is one of the most contagious of all infectious diseases, warns the CDC. As many as nine of 10 susceptible persons  with close contact involving a measles patient will develop the disease. It can also be transmitted by breathing, coughing, and sneezing, and can remain in the air up to two hours after an infected person leaves the area.

with close contact involving a measles patient will develop the disease. It can also be transmitted by breathing, coughing, and sneezing, and can remain in the air up to two hours after an infected person leaves the area.

There is no specific treatment, but symptoms could be addressed with acetaminophen (Tylenol) to reduce fever and relieve muscle pain, rest, and adequate hydration. The use of a humidifier might ease the symptoms of a cough and sore throat.

Moles

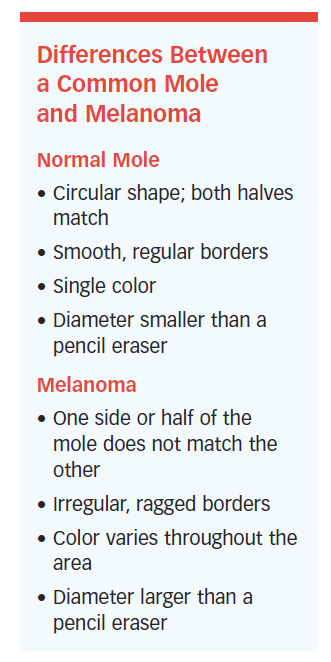

Moles are clusters or spots on the skin that consist of melanin cells called melanocytes, which give color to skin. They are either dark brown, reddish-brown, blue, or the color of skin. They vary in shape and size, but most are oval or round, and are less than one-quarter-inch in diameter.

Moles can be flat, raised, smooth, or wrinkled. Atypical moles are larger than a pencil eraser and usually have a dark brown center with a lighter, uneven border. They tend to run in families.

Bright red moles (cherry angiomas) are most likely to develop on the torso, arms, legs, or shoulders. They may begin to appear in a person’s 30s, and the number of moles tends to increase with age. They can be flat or slightly raised, round or oval-shaped, and range in size from a hardly-noticeable pinpoint to a quarter of an inch in diameter. Their reddish color is due to an abundance of small blood vessels. Red moles usually require no treatment unless you want them removed for cosmetic reasons or because they are bumped often and bleed. If you notice a change in the way a red mole looks, have a dermatologist examine it. If it has to be removed, it’s a relatively simple procedure of freezing it (cryosurgery), removing it by laser surgery, shaving it, or burning with an electric current (electrocauterization).

Most people have between 10 and 40 moles on average, and their presence was probably determined at birth. They can develop on any area of the body, including the scalp, between fingers or toes, and under fingernails and toenails.

The number of moles can change with age, with some fading as a person moves into adulthood, and others disappearing altogether or lasting 50 years or longer. Sunlight can increase the number of moles and make them darker.

Most moles are harmless and will never be a health threat, but in some cases they may lead to a higher risk of certain cancers. Traditionally, people who had the greatest number of moles were thought to have a greater risk of developing a melanoma.

A study in JAMA Dermatology suggested that physicians should not rely on the total number of moles as the only reason to perform an exam or determine a patient’s risk.

When to Call Your Doctor

The National Cancer Institute says to tell your doctor if you notice any of the following changes in a common mole:

- The color changes.

- The mole gets unevenly smaller or bigger.

- The mole changes in shape, texture, or height.

- The skin on the surface becomes dry or scaly.

- The mole becomes hard or feels lumpy.

- It starts to itch.

- It bleeds or oozes.

Moles or Melanomas?

University of Pennsylvania scientists appear to have discovered a gene (p15) that differentiates moles from melanomas.  By staining tissue samples, a low level of gene p15 indicated a melanoma. A high expression of p15 would be consistent with a benign mole.

By staining tissue samples, a low level of gene p15 indicated a melanoma. A high expression of p15 would be consistent with a benign mole.

A biopsy can determine if a mole is malignant, and a mole can be removed by shave excision (using a small blade to cut it out), punch biopsy (removing the mole with a small device that works like a cookie cutter), and excisional surgery (which involves taking out the mole and the skin around it). All of the procedures can be performed in a dermatologist’s office. Once removed, most moles do not recur. If one does, let your doctor know.

MRSA

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a potentially dangerous staph bacterium that is resistant to certain antibiotics. It may cause skin and other infections throughout the body. The bacterium is carried by 2 percent of the population, but few are infected. Those who have weak immune systems are most vulnerable, especially those in hospitals, nursing homes, and other health-care facilities. The symptoms of MRSA may include a fever, and a bump or infected area of the skin that has one or more of the following conditions:

- Red, swollen

- Painful, warm

- Filled with pus

Draining and Medication

Treatment may involve draining the infection and taking an antibiotic, and it is important to continue taking the medication even if the infection appears to get better. Oritavancin (Orbactiv) is given in a single dose and may become an option for the treatment of MRSA, and other skin infections.

Researchers at the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute have challenged the current CDC strategy for dealing with MRSA in hospitals, which stresses limited contact between patients and staff. Their research showed that bathing patients in a common hospital soap called chlorhexidine was just as effective as limiting contact, and could result in better quality of care because of increased contact.

Three anti-MRSA antibiotics—dalbavancin (Dalvance), oritavancin, and tedizolid—have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Preventing MRSA

The best ways to prevent MRSA are:

- Know the signs.

- Get treatment early.

- Practice good hygiene, especially by washing hands often.

- Do not share personal items, such as towels and razors.

- Follow prescription drug instructions precisely and complete the prescribed course, even if symptoms subside.

Take Your Medicine

A study published in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy found that patients with certain skin infections took, on average, only 57 percent of their prescribed antibiotic doses after leaving the hospital. Nearly half of 87 patients developed a new infection or needed additional treatment for the existing skin condition.

Poisonous Plants: Watch Out

Unless you live in Alaska, Hawaii, a desert, or at a high altitude, poison ivy is creeping around nearby. If you don’t stay away from it, you may be one of the 50 million Americans affected

each year.

Poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac all contain an oil called urushiol. It can cause an allergic reaction in the form of a blistering rash and an impossible-to-ignore itch. The poisonous plant presents three problems: recognizing it, treating it, and avoiding it.

Basic Summer Appearance

Poison ivy’s basic summer appearance is a vine or shrub that has green, three-leaf, pointed clusters. It can appear as ground cover, upright in bushes or shrubs, or as vines that grow up trees or rock walls. Several other plants (box elder, raspberries, blackberries) have a similar appearance. Poison ivy’s color changes with the seasons:

- In spring, the leaves emerge with a reddish color.

- In summer, they’re green. The plant may also have clusters of light green or cream-colored berries.

- In the fall, the leaves change to shades of red, orange, or yellow.

- In winter, its leaves disappear, but the leafless vines can still produce enough of the oil to cause a rash after contact.

Red Rash, Blisters, Itching

Poison ivy, oak and sumac are a year-round nuisance, but they are especially toxic in spring and summer. A nick or quick brush against the plant is all it takes. Its symptoms—a red rash, blisters, and itching—can appear within a few hours of exposure or as long as 12 days afterward. Without treatment, the symptoms go away in two to

three weeks.

If you know you’ve come into contact with poison ivy, oak or sumac flush your skin with lukewarm, soapy water as soon as possible (every minute counts), says the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD). Then do it again. Don’t scratch, and don’t break the blisters when they appear.

Oral antihistamines can relieve itching, as can wet compresses and short baths in warm or cool water. Over-the-counter topical corticosteroid preparations might help, or you might try trade-name products such as Calamine Lotion or Aveeno. See a doctor or go to the emergency room if:

- You have a temperature over 100°F.

- The affected area develops pus or soft yellow scabs.

- The rash spreads to your eyes, mouth, or genital area.

- You have trouble breathing.

- Home remedies haven’t done much to ease symptoms.

Not Contagious

There is some good news regarding a mostly-bad-news situation. The rash is not contagious and does not spread. It might appear to be spreading, but it’s because of a delayed reaction to urushiol in the areas of skin affected. Prevent exposure with these strategies:

- Wear long sleeves and pants tucked into garden boots if you are going to be working near poison ivy, oak or sumac. Use gloves that don’t allow fluids, including oils, to pass through.

- Wash any item of clothing that has been in contact with poison ivy, oak or sumac, and regularly wash garden tools.

- Use pet shampoo to wash a dog that may have brushed against one of these plants. Pets aren’t sensitive to the oil, but if it gets on their fur and you touch it, you’ll have a reaction.

- Don’t put poison ivy, oak or sumac leaves in a campfire or when burning leaves in your yard. Urushiol can become airborne.

Protection by Avoidance

Poison ivy, oak, and sumac can be easily pulled out in early spring if only a few plants are involved. Pull out the entire root system, if possible, and put it in a plastic bag to be taken away.

When the plants have been in an area for a long time, it is almost impossible to remove the plant and its root system. The best way to protect yourself is to stay away from it.

Plaque Psoriasis

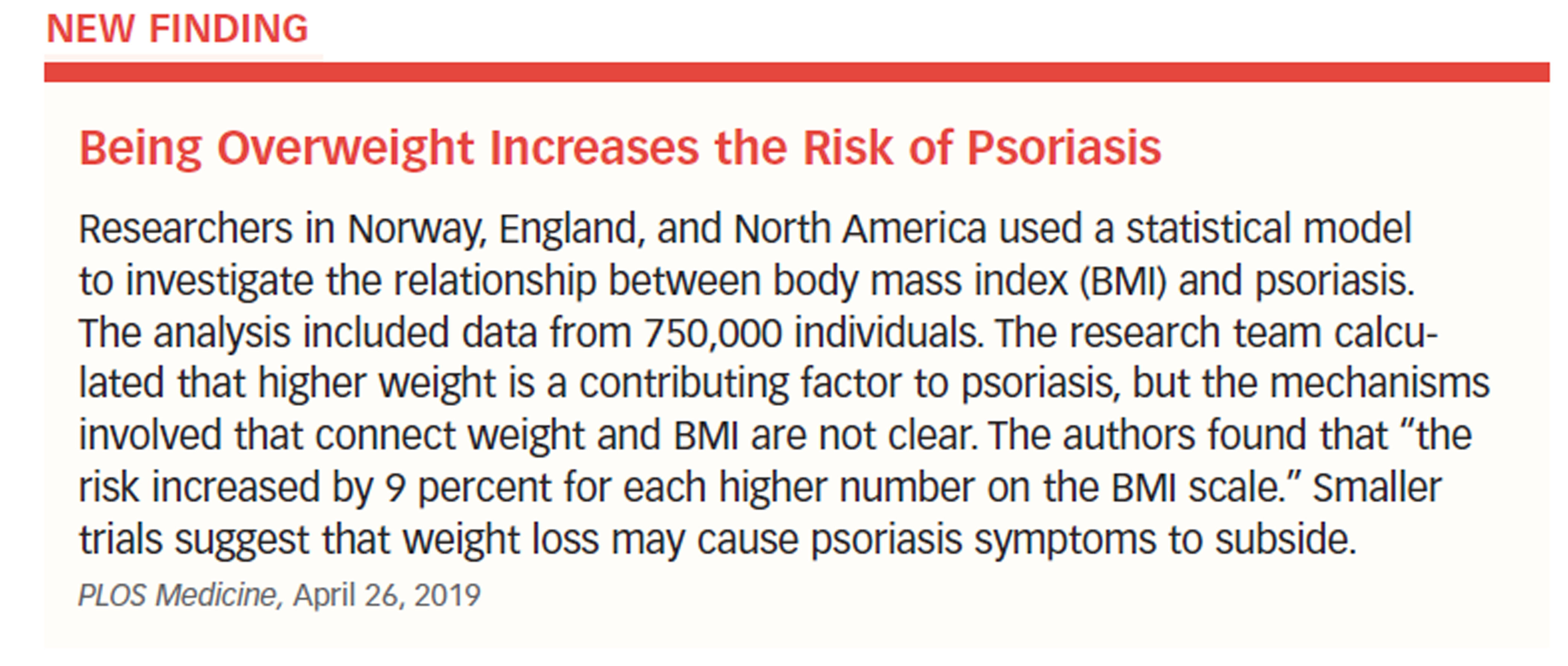

Even though psoriasis affects up to 8 million people in the United States, about 40 percent of psoriasis patients do not get treatment. There are five types of psoriasis, and each has unique symptoms, but 80 percent of people get the most common variety: plaque psoriasis.

Even though psoriasis affects up to 8 million people in the United States, about 40 percent of psoriasis patients do not get treatment. There are five types of psoriasis, and each has unique symptoms, but 80 percent of people get the most common variety: plaque psoriasis.

Risk Factors

Psoriasis and other diseases are associated with metabolic syndrome (a group of risk factors associated with diabetes and stroke that include a large waistline, high triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol, high blood pressure, and high fasting blood sugar). Psoriasis may be a precursor to diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Approximately one-third of psoriasis patients have a family history of the disease.

T-Cells Rising

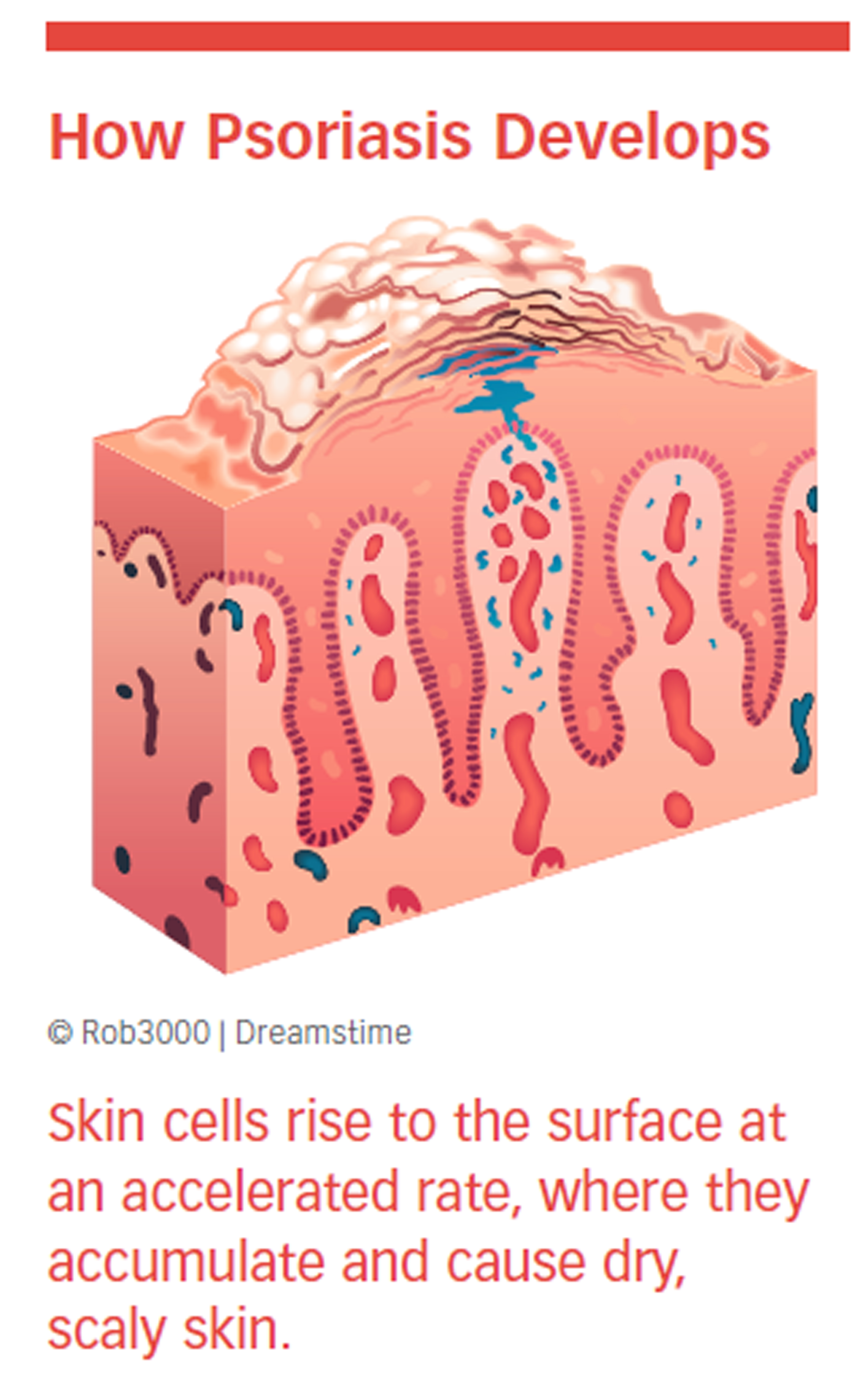

Psoriasis occurs when T-cells that normally protect the body against infection and disease develop and rise to the surface at a faster-than-normal rate. They accumulate on the top layer of skin before they have time to mature.

The discovery of a mutation in the CARD14 gene suggests that the mutation, plus an environmental trigger, is enough to  cause psoriasis. Scientists now have a much clearer picture of what is happening in psoriasis, and targeted therapies are being developed.

cause psoriasis. Scientists now have a much clearer picture of what is happening in psoriasis, and targeted therapies are being developed.

Skin cell turnover usually takes about a month, but in psoriasis it can happen in a few days. This process results in patches of thick, inflamed skin covered with scales that itch and can hurt.

They appear anywhere on the body, but show up  most often on the elbows, knees, legs, lower back, face, palms, soles of the feet, and scalp. The symptoms can be only a nuisance or serious enough to interfere with work, recreation, and daily life and functions.

most often on the elbows, knees, legs, lower back, face, palms, soles of the feet, and scalp. The symptoms can be only a nuisance or serious enough to interfere with work, recreation, and daily life and functions.

Patches, Scales, Cracked Skin

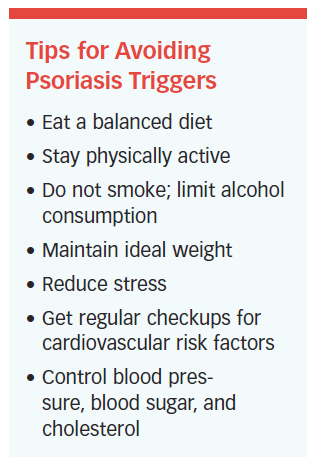

Symptoms include red patches, silver scales, dry skin, cracked skin that can bleed, thick or ridged nails, and swollen or stiff joints. A new episode can be triggered by infections, injuries to the skin, smoking, cold temperatures, stress, alcohol consumption, and certain medications, including lithium, beta blockers, and antimalarial drugs. Excessive body weight also can increase the risk of psoriasis.

Excessive inflammation is a critical feature, and since it is also a characteristic of insulin resistance, obesity, high cholesterol levels, and cardiovascular disease, psoriasis patients should consult with their health-care providers to watch closely for signs of these conditions.

Treatable, Not Curable

Psoriasis can be difficult to diagnose. It is not curable, but it is treatable. See a doctor if your condition is more than a nuisance, if it interferes with daily activities, and if you are concerned about the appearance of your skin. If your doctor cannot make a diagnosis by observation, he or she will take a skin sample and examine it under a microscope.

Physicians often use a three-step treatment approach, which includes topical medication, phototherapy, and oral or injectable drugs.

Step 1 (one or more of the following):

- Corticosteroids to reduce inflammation and slow cell turnover.

- Calcipotriene, a synthetic form of vitamin D, to limit cell production.

- Retinoids, a synthetic form of vitamin A, to normalize DNA activities in cells.

- Moisturizers to reduce itching, scaling, and drying.

Step 2 (to calm cellular response):

- Photodynamic therapy to slow the rate of cell turnover.

Step 3 (one or more of the following):

- Methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall)

- Cyclosporine (Gengraf, Neoral)

- 6-Thioguanine

- Hydroxyurea (Droxia, Hydrea, Siklos)

- Antibiotics

- Biologics

At-Home Treatment

The AAD suggests several strategies for dealing with psoriasis. They include:

- Bathe daily to remove scales and reduce inflammation, but avoid hot water and harsh soaps.

- Use moisturizers to prevent drying of the skin.

- Cover affected areas at night with moisturizers, and lightly cover with plastic food wrap.

- Use cortisone to reduce inflammation, such as over-the-counter creams with 0.5 to 1 percent cortisone.

- Avoid triggers such as stress, smoking, excessive sun exposure, and drinking alcohol.

- Try not to scratch.

Alternative Therapies

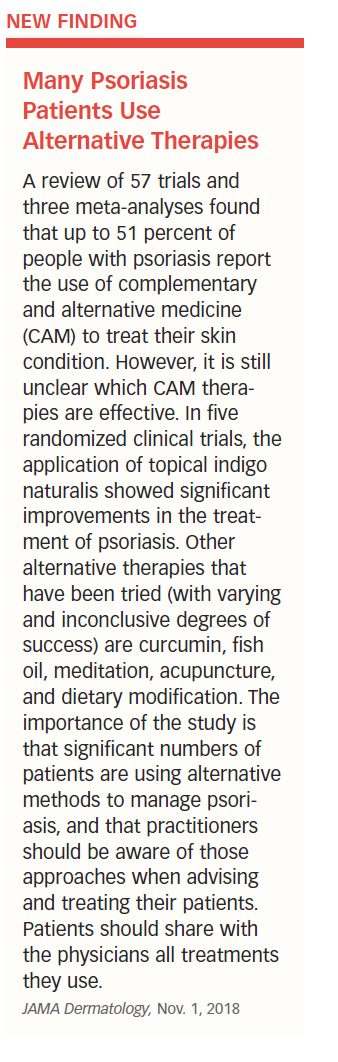

Although they do not always report it to their physicians, significant numbers of people are using alternative methods to  treat skin conditions. In the case of psoriasis, a recent study found that up to 51 percent of patients with psoriasis were using complementary or alternative medical approaches (see “Many Psoriasis Patients Use Alternative Therapies”).

treat skin conditions. In the case of psoriasis, a recent study found that up to 51 percent of patients with psoriasis were using complementary or alternative medical approaches (see “Many Psoriasis Patients Use Alternative Therapies”).

Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is a form of inflammatory arthritis. Its symptoms vary widely and make it difficult to diagnose, even for physicians. X-rays, joint fluid tests, and blood tests are used to make the diagnosis.

Patients report pain and stiffness in the knees, ankles, and joints of the feet, although other areas can be affected. Inflamed joints may be swollen and hot, and stiffness and pain are often worse in the morning than at other times. Patients also may have inflamed tendons and inflammation in the eyes, lungs, and aorta. Acne is a common side effect.

Psoriatic arthritis can develop at any age, but it most often occurs in adults between ages 25 and 50. Genes, environmental factors, and the immune system appear to play a role in its development. Psoriasis precedes psoriatic arthritis by months or even years.

Treat the Symptoms

The goal of treatment is to suppress symptoms rather than cure the disease. Doctors first try nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), and naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn).

If they don’t work, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, such as methotrexate, antimalarials, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, are prescribed. TNF drugs, such as etanercept (Enbrel), infliximab (Remicade), and adalimumab (Humira), are effective for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

The FDA has approved the drugs golimumab (Simponi) and ustekinumab (Stelara) for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. They also have approved a drug called apremilast (Otezla) to treat psoriatic arthritis by blocking enzyme-related inflammation.

A rheumatologist should treat psoriatic arthritis if arthritis is the focus. If the primary symptoms involve only the skin, a dermatologist can treat them.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Don’t let the name fool you. Although the Rocky Mountain states are where it was first identified, Rocky Mountain spotted fever is more common in the southeastern and southcentral states than in other parts of the country.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is caused when an infected wood tick or yellow dog tick bites a person. People are bitten most often from March to September, when the ticks are active and people are in tick-infested areas.

Rash, Headache, Fever

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is a serious and sometimes deadly bacterial infection that begins with a rash, headache, and high fever that can get worse quickly if it’s not diagnosed and treated. The rash does not itch, but it spreads rapidly from the wrists and ankles in both directions to the palms, soles, forearms, necks, armpits, buttocks, and trunk—however, 10 percent of people with the condition do not develop a rash.

Untreated cases of the disease result in death up to 80 percent of the time. Early treatment with antibiotics has reduced the death rate to about 5 percent.

Prevention

- Tuck trousers into shoes, socks, or boots.

- Stay on paths and trails.

- Wear light-colored clothing to spot ticks more easily.

- Wear long-sleeved shirts.

- Use tick repellants containing DEET.

- Search quickly for tick bites.

- Remove ticks immediately.

Rosacea

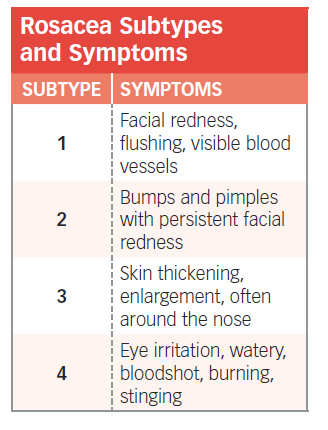

Rosacea is a common, chronic, incurable condition characterized by redness and visible blood vessels in the face. It has been classified into four subtypes, which are described by the National Rosacea Society (NRS). See “Rosacea Subtypes and Symptoms.” More than 16 million people in the United States have rosacea and most of them don’t know it.

Cheeks, Chin, Nose

The cheeks, forehead, chin, and nose are the primary targets of rosacea. The neck, ears, chest, and back are less frequently involved. In 50 percent of people with rosacea, the eyes may be watery, red, or irritated. Other possible symptoms are a sensation of burning, itching, or stinging, dry or thick skin, and facial swelling.

Individuals most susceptible to rosacea have fair skin, blush easily, are between ages 30 and 60, and have a family history of the condition. Women are affected more often than men, but that may be because men wait longer to seek treatment.

Cause Unknown

The cause of rosacea is unknown, but recent research revealed that an immune response might play a role in its development. Through skin biopsies, a team of international researchers found that people with rosacea had unusually high levels of cathelicidins (types of proteins), peptides, and inflammatory properties that protect skin against infection. They also discovered that an enzyme known as SCTE was elevated in people with rosacea.

Family History

A family history of rosacea places people in a higher risk category, as do high rates of blistering sunburn. The NRS reports a connection between rosacea and national origin. Individuals with Irish, English, and German ancestry appear to be at higher risk.

Psychological Consequences

Rosacea has psychological as well as physical consequences. A survey conducted by the NRS found that more than 75 percent of patients said their condition lowered their self-confidence and self-esteem. Fifty-two percent said it was the reason they avoided public contact and frequently cancelled social engagements.

Risk of Cancer Increased

A study of 49,475 rosacea patients in Denmark found that, when compared to a control group of more than 4 million people, those with the condition had higher rates of liver cancer, non-melanoma skin cancer, and breast cancer, but a decreased risk of lung cancer. The findings were published in the journal Cancer Epidemiology.

If rosacea is not treated, it always gets worse, and sometimes progresses into a more serious condition called rhinophyma, which affects the nose, giving it a red, bulbous appearance. Ninety percent of rosacea patients say their condition is controlled with treatment.

Medications Take Time

Topical medications include azelaic acid, benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, erythromycin, metronidazole, sulfacetamide,  and sulfur lotions. Keep in mind that it might take two or three months to get significant results. In 2014, the AAD issued a statement acknowledging that skin prone to acne or rosacea may improve with daily probiotic use.

and sulfur lotions. Keep in mind that it might take two or three months to get significant results. In 2014, the AAD issued a statement acknowledging that skin prone to acne or rosacea may improve with daily probiotic use.

Studies specifically associating probiotics and rosacea are scarce. A 2017 study in Dermatology Practical & Conceptual concluded, “[Rosacea] patients may be advised to support a healthy gut microbiome, including the consumption of a fiber-rich [prebiotic] diet.” Given that proper microbe balance within the gut is beneficial, research continues on how probiotics might help reduce the inflammatory responses that result in acne and rosacea.

Pimples and bumps may respond better to oral antibiotics, including doxycycline (Adoxa, Monodox), erythromycin, minocycline, and tetracycline (Periostat, Vibramycin).

Oral antibiotics also may be combined with glycolic acid peels and glycolic washes and creams. Isotretinoin is not approved by the FDA for this condition, but some doctors prescribe it (off-label use) to help shrink facial skin that has thickened. However, it can have serious side effects, such as nosebleeds, dry skin, dry mouth, and itching.

The FDA approved the topical cream ivermectin (Soolantra) in 2014 for the treatment of inflammatory lesions of rosacea. Subjects who used the cream achieved “clear” or “almost clear” rates 38 to 40 percent of the time, compared with 7 and 19 percent of the time in a control group.

When the eyes are affected, patients should gently clean their eyelids with diluted baby shampoo, or an over-the-counter eyelid cleaning substance. Warm compresses applied several times a day also might relieve the symptoms. Oral antibiotics, such as doxycycline, minocycline, or tetracycline, are prescribed at times.

Dermatologists may use electrosurgery or laser surgery to address redness and flushing. Among recent innovations are pulsed dye lasers that destroy visible blood vessels and reduce flushing and redness. Intense pulsed light therapy delivers light to the affected areas, where it targets blood vessels and redness.

Avoid Triggers

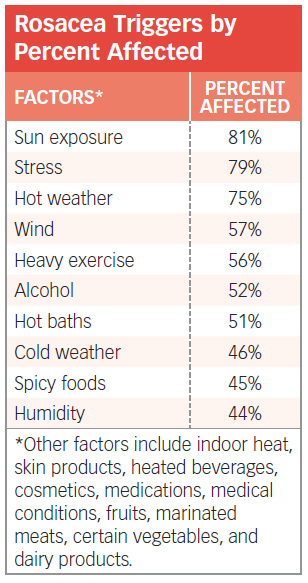

Rosacea cannot be prevented, but the symptoms can be controlled once they have developed. The first step is to avoid possible triggers. “Rosacea Triggers by Percent Affected” shows the results of a survey taken by the NRS of more than 1,000 patients regarding factors that produce an episode.

Rosacea cannot be prevented, but the symptoms can be controlled once they have developed. The first step is to avoid possible triggers. “Rosacea Triggers by Percent Affected” shows the results of a survey taken by the NRS of more than 1,000 patients regarding factors that produce an episode.

Use a 30 to 50 SPF sunscreen when outdoors, and a moisturizer during winter to prevent dry skin. Consider keeping a diary to identify substances, activities, and environments that could possibly cause a flare-up.

Scabies

Older adults, especially those with weakened immune systems, are at a higher risk for scabies than younger, healthier people. Scabies is an infestation of the skin by a microscopic mite. It is a common condition found around the world, and spreads rapidly in crowded conditions where there is frequent skin-to-skin contact. It can happen in hospitals, nursing homes, and other institutions, but prolonged contact is usually needed to transmit the infection. A casual handshake or hug is unlikely to cause a problem.

It could take four to six weeks after contact for symptoms to develop. The symptoms include skin irritation or a rash, usually between the fingers or on the wrists, elbows, knees, breasts, or shoulder blades. Your doctor can prescribe a topical cream or lotion to get rid of the infestation, although the symptoms may last a week or two longer.

Seborrheic Keratosis

Seborrheic keratosis (SK) looks like a wart-like tumor on the surface of the skin and may be mistaken for skin cancer. It is neither, but SK is a common skin growth in older adults.

SK can be yellow, brown, black, or other colors. The lesions are more common on the face, chest, shoulders, and back than on other places of the body. Some of them turn black, which is why they may be mistaken for skin cancer, but biopsies almost always determine them to be noncancerous.

SK can appear alone or in clusters, have a rough or smooth texture, and do not penetrate deeply into the skin. They can be quite small or more than one inch in diameter and are painless. However, rubbing or scratching can cause inflammation.

Family History

Descriptions of SK include the term “stuck on” or “pasted on,” as if someone dabbed a patch of candle wax onto the skin. They are not contagious, but they do seem to run in families.

Their cause is unknown, though as the name suggests, SKs emit an oily, waxy substance similar to that produced by sebaceous glands. Expert opinions are mixed as to whether ultraviolet (UV) light exposure causes SK.

The AAD says exposure to sunlight does not seem to be a cause or a complicating factor after SK has developed. However, others say exposure to sunlight may be a factor because the condition is common in areas often exposed to the sun.

Unsightly, Not Dangerous

The best news about SK is that it is not dangerous, and usually does not need to be removed. People who have them removed do so because of their unsightly appearance or because the growths get irritated, itch, or bleed. Insurance companies do not cover procedures to remove them for cosmetic purposes.

Also, do not waste your money on creams, ointments, or other over-the-counter products that claim to remove the growths. They don’t work.

A dermatologist can remove an SK during an office visit by cryosurgery (using liquid nitrogen), curettage (scraping them off the skin), electrosurgery (by means of an electrical current, sometimes combined with curettage), or laser surgery (using high-intensity light beams to destroy the growth). In 2017, the FDA approved ESKATA, a topical solution for the treatment of seborrheic keratosis.

Don’t confuse seborrheic keratosis with actinic keratosis. Actinic keratosis, also called solar keratosis, is considered to be the earliest stage of skin cancer that is limited to the outermost layer of skin.

Shingles

Almost one in three people in the United States will develop shingles during their lifetime. Two-thirds get it after the age of 50. Most will get it once, but it’s possible to get it a second or third time.

of 50. Most will get it once, but it’s possible to get it a second or third time.

Shingles causes a rash or blisters on the skin. It is a viral disease—the same one that causes chickenpox. After chicken pox heals, the virus becomes dormant in the body, but it can emerge again if a person’s natural resistance is compromised.

Those who are at the greatest risk for shingles have a weakened immune system, are over the age of 50, have been ill, are experiencing trauma, and/or are under stress.

The symptoms of shingles often include itching, stabbing, or shooting pains. The skin appears red in the affected area. Other symptoms are fever, chills, headache, and an upset stomach. A rash appears after a few days around the waistline or on one side of the face or trunk.

Antiviral Medications

There is no cure for shingles, but treatment with antiviral medications—such as acyclovir (Zovirax), valacyclovir (Valtrex), and famciclovir (Famvir)—can help ease the pain and discomfort and reduce the duration of symptoms.

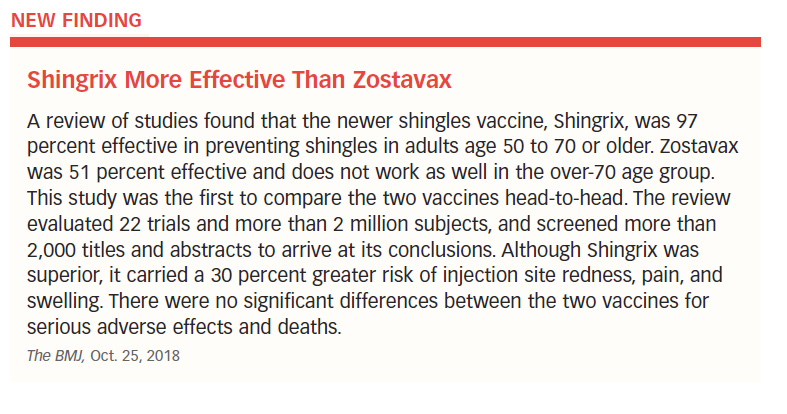

The vaccine Shingrix was approved by the FDA in 2017. The CDC recommends that healthy adults 50 years and older get two doses of Shingrix, two to six months apart. Pain, redness, swelling at the injection site, and muscle pain are possible side effects.

A review of 27 studies involving more than 2 million patients found that Shingrix was 97 percent effective in preventing shingles compared to Zostavax, which was 51 percent effective. (see “Shingrix More Effective Than Zostavax”).

Skin Tags

A skin tag is a small, benign, elongated, skin-colored growth that is common in people older than age 60. The condition is also known as an acrochordon. It is made up of a core of fibers and ducts, nerve cells, fat cells, and a covering. Some have a stalk.

A tag sticks out of or looks like it is hanging from the skin, usually near the neck, armpits, trunk, breasts, or other areas of the body where the skin folds. Some may be darker than the skin color.

A tag sticks out of or looks like it is hanging from the skin, usually near the neck, armpits, trunk, breasts, or other areas of the body where the skin folds. Some may be darker than the skin color.

Skin tags occur in approximately 46 percent of the population, and the incidence increases with age. The number goes up to 59 percent by the age of 70.

Skin tags are present in both men and women, although they are associated with pregnancy in some women. Skin tags are also more common in people with type 2 diabetes and in those who are obese. Two studies have found that people who have multiple tags were more likely to have insulin resistance.

Skin tags appear to have an association with metabolic syndrome. There is some evidence that susceptibility may be genetic.

Skin tags do not grow (they are usually just a fraction of an inch in diameter), they do not hurt, and they are not a form of skin cancer. The can be unattractive and become irritated if clothes or jewelry rub against them. They may develop because of skin rubbing against skin and are more common in those who are overweight or have diabetes. Unusually large tags may burst and bleed under pressure.

Quick, Painless Treatment

A skin tag is easily diagnosed and treated. It can be removed during an office visit by excision (cutting it out), cryotherapy (freezing it), cauterization (burning it off with an electrical current), or ligation (interrupting the blood supply). Removing larger tags may require a local anesthetic. A skin tag on the eyelid may have to be removed by an ophthalmologist.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) do not recommend that a person attempt to remove a skin tag without medical assistance because of the risk of bleeding and infection. Over-the-counter products are available, but not recommended by any national health organization in the United States.

Tags do not normally come back at the same site, but new growths can develop elsewhere on the body. There is no evidence that removing a skin tag causes more to develop. Some tags just fall off, but in most cases, they don’t.

You cannot prevent skin tags—they just happen. But unless they regularly become irritated, unsightly, or change in color, size, composition, or sensitivity, there is no reason to treat or report them.

Sunburn Consequences

Many skin diseases are caused by overexposure to the sun. If the sun does not cause them, many are made worse by exposure to the sun’s UV rays. However, there are benefits to sun exposure, particularly in the case of UV rays, which help the body produce vitamin D that older adults often lack.

The key is to minimize your sun exposure and make efforts to protect yourself at all times. Of course, the most immediate, short-term problem caused by the sun is sunburn.

According to the NIH, sunburn occurs when the amount of exposure to UV rays, whether from the sun or from artificial sources, exceeds the body’s ability to produce melanin. Melanin is a protective pigment responsible for tanning, and a suntan is the body’s way of shielding itself against UV rays.

Four Hours After Exposure

Sunburn symptoms begin to appear about four hours after exposure, get worse during the next six to 48 hours, and begin to subside in three to five days. In a mild case of sunburn, the skin becomes red or pink, warm, and tender. In more severe burns, the symptoms also include pain, swollen skin, and possible blisters.

By the time your skin is painful and red, the damage has been done. If a large area is burned, you might have a headache, fever, nausea, or fatigue. The skin will begin to peel three to eight days after exposure. Recovery ranges from several days to three weeks.

Any part of the body can be sunburned, including the eyes. Sunburned eyes are red, dry, painful, and gritty-feeling. Long-term effects of chronic exposure to the sun include cataracts and perhaps macular degeneration, an age-related loss of central vision.

Older adults and young children are more susceptible to sunburn than young and middle-aged adults. A study of more than 100,000 nurses found that those who had at least five blistering sunburns between the ages of 15 and 20 had an 80 percent higher risk for melanoma, and a 68 percent greater risk of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

Not everyone reacts to the sun the same way. It often depends on skin type, length of exposure, time of day and year, geography, and drugs that a person is taking.

Importance of Skin Type

Of the many factors associated with sunburn, one of the most important is skin type. Several organizations, including the Skin Cancer Foundation, classify skin types from light to dark (see Chapter 3).

The closer you are to Type I (very fair, white skin), the greater your risk of sunburn now and skin cancer later. The darker your skin, the more pigmentation it has to protect itself against the sun.

Length of Sun Exposure

A Type I or Type II person can get a sunburn in as little as 15 minutes, while a person with darker skin may be able to tolerate the same amount of exposure for several hours.

Time of Day

The highest risk for sunburn is between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m., and exposure during the summer months is most dangerous.

High-Risk Locations

Snow, water, and light-colored sand reflect UV rays and increase the chances you will suffer sunburn. Keep in mind that clouds may feel like protection, but in fact they do not help, as up to 80 percent of UV rays penetrate cloud cover. The higher the elevation and the closer you are to the equator, the greater your risk. The worst possible situation would be swimming or snow skiing at a high altitude in a country near the equator.

clouds may feel like protection, but in fact they do not help, as up to 80 percent of UV rays penetrate cloud cover. The higher the elevation and the closer you are to the equator, the greater your risk. The worst possible situation would be swimming or snow skiing at a high altitude in a country near the equator.

Drugs That Increase the Risk

Several drugs increase your sensitivity to sunlight and the risk of being burned. Among them are ibuprofen, sulfa antibiotics (Gantanol), doxycycline, tetracycline, and diuretics (Diuril, Edecrin).

No Quick Cure

There is no quick cure for sunburn. Aspirin, acetaminophen (Tylenol), and ibuprofen relieve pain and reduce fever. Drink plenty of water to replace lost fluids. Cool baths and wet cloths might feel good, as will moisturizing creams. A low-dose (0.5 to 1 percent) hydrocortisone cream might reduce the burning sensation and hasten the healing process.

If blisters develop, cover the area with a light bandage or gauze. Breaking the blisters will increase the possibility of infection, so allow them to resolve on their own.

If blisters develop, cover the area with a light bandage or gauze. Breaking the blisters will increase the possibility of infection, so allow them to resolve on their own.

See a doctor if more than 15 percent of your body is affected (for example, the upper and lower back, plus the buttocks, constitute 18 percent of your body’s skin). Also seek medical help if you are dehydrated, have a fever exceeding 101°F, or the pain persists longer than 24 hours.

Reducing the Risk

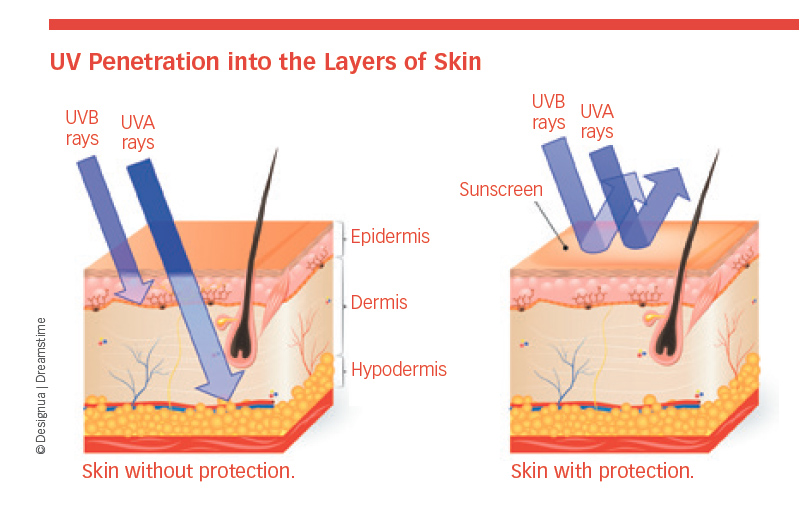

Sunscreen makes a significant difference in how the sun’s rays penetrate skin. To understand how deeply ultraviolet-A and ultraviolet-B rays penetrate the skin with and without protection, see “UV Penetration into the Layers

of Skin.”

- Protect yourself by following these tips from the CDC and NIH:

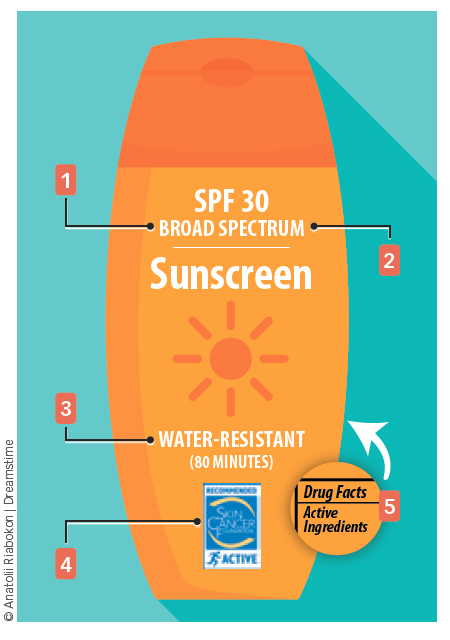

- Use a full-spectrum or broad-spectrum sunscreen of 30 to 50 SPF.

- Apply sunscreen 20 minutes before being exposed to the sun, and reapply every two hours—sooner if you are in and out of water, or if you perspire heavily.

- Wear dark clothing with a tight weave to block UV rays.

- Wear a wide-brimmed hat that protects the scalp, face, ears, and neck.

- Avoid tanning beds.

Protection Not Guaranteed. Use of a sunscreen does not guarantee protection against skin cancer. A study in Norway found that although some people use sunscreen, they don’t necessarily apply the right amount, they forget to reapply, or they don’t apply it to all exposed areas.

A second study of more than 2,187 participants conducted by University of Minnesota researchers found that use of sunscreen decreased on cloudy days even though 80 percent of the sun’s rays can still penetrate cloud cover, and that men used sunscreen less often than women.

A second study of more than 2,187 participants conducted by University of Minnesota researchers found that use of sunscreen decreased on cloudy days even though 80 percent of the sun’s rays can still penetrate cloud cover, and that men used sunscreen less often than women.

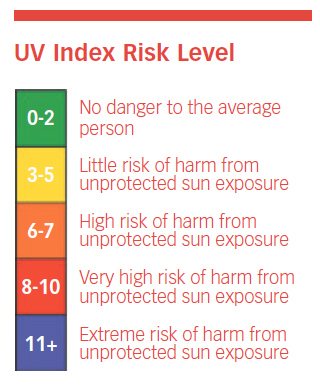

UV Index Explained. Before you venture outside, always check the UV Index Risk Level provided by the Environmental Protection Agency. The index ranges from a low of one to a high of 11. Take extra precautions when the index is six to seven or higher.

Look for Your Shadow. An easy way to tell how much UV exposure you get is to look for your shadow. If your shadow is taller than you (like in the early morning and late afternoon), your UV exposure is likely to be low. If your shadow is shorter than you (around midday), you are being exposed to high levels of UV radiation. When this occurs, seek shade and take precautions to protect your skin and eyes.

Slip, Slop, Slap, Seek, Slide. One of the most successful health education initiatives ever conducted in Australia was called “Slip, Slop, Slap”—Slip on a shirt, Slop on sunscreen, and Slap on a broad-brimmed hat. The original slogan has now been expanded to “Slip, Slop, Slap, Seek, and Slide,” and exported to the United States and other countries. “Seek” means to find some shade. “Slide” is a bit of a grammatical stretch, but good advice: Slide on a pair of wrap-around sunglasses.

“Slip, Slop, Slap”—Slip on a shirt, Slop on sunscreen, and Slap on a broad-brimmed hat. The original slogan has now been expanded to “Slip, Slop, Slap, Seek, and Slide,” and exported to the United States and other countries. “Seek” means to find some shade. “Slide” is a bit of a grammatical stretch, but good advice: Slide on a pair of wrap-around sunglasses.

Tattoos

They say that the two happiest days of a boater’s life are the day they buy a boat and the day they sell it. The same might be said of people who get tattoos.

The prevalence of “tattoo regret” has skyrocketed, and the tattoo removal business is up 440 percent over a recent 10-year period. The industry has the potential for more growth as younger, tattoo-friendly generations age.

The risks of tattoos include allergic reactions, skin infections, granuloma (inflammation), bloodborne diseases, and possible interference with magnetic resonance imaging.

The most efficient way to remove a tattoo is with a “quality-switched” laser. Its high-intensity light beams break tattoo ink into particles small enough for the body to absorb.

Laser tattoo removal has limitations in the colors it can erase and with the added difficulty caused by more vibrant tattoo colors, according to the British Journal of Dermatology. People with darker pigmented skin tend to have less success with certain lasers and require more sessions to avoid skin damage.

It takes three to 10 treatment sessions to remove a tattoo, generally scheduled four to six weeks apart. There is no guarantee that a tattoo will be completely erased, but it’s possible, and something (partial removal) might be better than nothing (having a tattoo that you no longer want).

Vitiligo: Loss of Skin Color

In vitiligo, the skin loses its color and white patches develop because the melanin cells are destroyed. The condition can occur anywhere on the body, including the skin, hair, scalp, eyebrows and eyelashes, and beard.

The exact cause is not known, but a combination of genetic, immunologic, and environmental factors might be involved. Some people attribute their onset of vitiligo to stress or an emotional trauma, such as an accident or the death of a friend or family member.

Whatever the cause, certain people seem to have a greater tendency to develop the condition when exposed to the right (or wrong) trigger. The loss of hair or skin color often begins before the age of 40. Vitiligo can have an emotional impact because the skin is not evenly colored.

Limited Treatment

Repigmentation therapy—which involves recruiting new pigment cells from nearby areas of skin or hair—is one approach to restore pigment. Its effects are limited by the time required and the space to be re-pigmented.

Other approaches involve topical compounds, phototherapy, and surgery. Complete repigmentation is rare. The final, and perhaps best, strategy for some people is the use of cosmetics to cover the discolored skin.

The drug tofacitinib (Xeljanz), normally used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, may be effective to restore skin color to vitiligo patients. Treatment with tofacitinib promotes the growth of melanocytes. A combination of two treatments for vitiligo may be more effective than either treatment alone, according to a 2018 study published in JAMA Dermatology.

Warts

Common warts, foot warts (also called plantar warts), and flat warts are all noncancerous growths caused by a virus in the human papillomavirus, family. They can develop almost anywhere on the body and are usually the color of your skin.

Common warts are more likely to appear on the hands, especially where the skin has been broken. Foot warts develop on the soles of the feet, but do not usually grow out of the skin because the pressure of walking pushes them back into the bottom of the foot.

Flat warts are smooth and small, but as many as 100 can develop in a single area. They often occur on the face in older men and on the legs of women. The warts may be associated with shaving those areas, but scientists have been unable to prove that theory.

Risk of Transmission Is Small

Warts can be transmitted from one person to another, but the risk is small. The time between contact with another person and developing a wart is several months. Contact does not have to be direct, either. Sharing towels and other items with someone who has warts could facilitate the virus’s transfer. Some warts go away on their own, while others have to be removed because they cause a problem.

When to Call Your Doctor

Warts should be removed only if they are unsightly, painful, or bleeding. One home remedy is to apply salicylic acid (contained in the over-the-counter product Compound W) to warts on the hands, feet, or knees. The acid has to be applied every day for several weeks.

A doctor might apply a chemical called cantharidin to destroy the wart. A second visit is needed to remove the dead skin. Dermatologists also use liquid nitrogen to freeze a wart, and two to four treatments over a period of several weeks are necessary to remove the growth. Immunotherapy, laser therapy, and injecting each wart with an anticancer drug called bleomycin are used less frequently than more conservative methods.

Warts can reappear almost as fast as existing ones go away, probably because the virus is still present in the general area. The only way to deal with this problem is to treat the new growths as soon as possible to prevent the leftover virus from infecting nearby skin.

Wrinkles

Wrinkles are a fact of life—or more specifically, a fact of aging—but they can be more pronounced and develop earlier among people who smoke, are over-exposed to sunlight, exposed at all to indoor tanning, or are chronically dehydrated.

Even facial expressions can lead to fine lines. Young skin springs back; older skin, not so much. Wrinkles will appear most often in parts of the body that are frequently exposed to sunlight—face, neck, hands, and arms.

Hundreds of products, as well as clinical procedures, have made their way to the market. Some work; some don’t. Here’s an update on what the research-based evidence says.

- Over-the-counter creams: Ingredients include retinol, vitamin C, hydroxy acids, peptides, coenzyme Q10, and others. Effectiveness, according to the Mayo Clinic, depends in part to which ingredient is included. Most contain lower concentrations of prescription medications. No single product works for everyone. Results, if any, are modest and short-lived.

- Prescription medications: Retinol is one of the most common prescription ingredients. According to the Harvard Medical School, retinol reduces fine lines and wrinkles by increasing the production of collagen. It takes three to six months of regular use before improvement is apparent, and the medication must be used continually to maintain its benefits.

- Dermabrasion: Dermabrasion, says UCLA Health, involves using a high-speed rotating brush to remove the top layer of skin. The degree of wrinkling determines the appropriate level of skin that will be removed. Results could take several months and are temporary.

- Laser resurfacing: Laser resurfacing removes or softens wrinkles. It provides controlled shedding of damaged skin, which exposes a new layer of skin, according to the American Academy of Facial, Plastic, and Reconstructive Surgery. It also stimulates new cell growth. Results are not guaranteed and depend on multiple skin-related factors.

- Radiofrequency: Radiofrequency energy is used to tighten the skin and reduce wrinkles. The AAD reports that noticeable skin tightening starts to occur within one month of treatment, with best results visible in four months.

- Chemical peel: A chemical peel uses a solution to improve the skin’s appearance by removing the damaged outer layers according to UCLA Health. The healing process takes from one day to three weeks, depending on the type of peel. Possible side effects are redness, scarring, changes in skin color, and infection. It is not for everyone.

- Botox: Botulinum toxin (Botox, Dysport) was approved by the FDA for the treatment of wrinkles in 2013. It temporarily paralyzes muscle tissue to reduce the appearance of wrinkles. A 2016 study published in the Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research found that treatment with botulinum toxin is a simple, safe, and effective way to reduce forehead wrinkles. Results last up to four months.

- Soft tissue fillers: Soft tissue fillers, according to the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, contain some form of hyaluronic acid, which occurs naturally in the body. The results depend on location and depth of the wrinkles. The effect on reducing wrinkles lasts 6-24 months.

Prevention Looks Familiar

The risk of overexposure to sunlight cannot be overemphasized. Limit your exposure, use broad-spectrum sunscreens with a SPF of 30 or more, apply moisturizers, don’t smoke, and eat lots of fruits and vegetables.

In Chapter 6

There is one specific type of precancerous condition you should be aware of, and four types of cancer itself. All are described in Chapter 6.

The post 5. Skin Conditions: Lyme Disease to Wrinkles appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 5. Skin Conditions: Lyme Disease to Wrinkles »