4. Diseases and Disorders of the Stomach

The stomach is situated on the upper left side of the abdomen, and its size varies between individuals depending on their size, build, and gender. The stomach is where food is mixed with gastric acid and enzymes, and predigested. The walls of the stomach comprise layers of mucous membrane, connective tissue, and muscle fibers. The muscles of the stomach churn food vigorously, breaking it down into a smooth pulp before it is passed on into the small intestine via a narrowed channel called the pyloric canal.

Gastritis

Gastritis is not a single disease, but rather a condition with several possible causes. The term “gastritis” means inflammation of the stomach lining. When the body’s immune system detects injury from infection or other cause, it produces inflammation, which triggers processes that promote healing. Healing occurs as the inflammatory process abates. If the cause of injury persists, the immune system continues to respond, causing ongoing inflammation, and healing will not occur.

Some possible causes of gastritis include alcohol abuse, prolonged use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), or infection with the Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) bacteria. Most people infected with H pylori do not experience symptoms, because the inflammation is mild. However, certain factors can worsen the inflammation and cause symptoms of gastritis to appear. Pernicious anemia, autoimmune disorders, and chronic bile reflux can also cause gastritis.

Gastritis Symptoms

The most common symptoms of gastritis are upset stomach, indigestion, and pain in the upper abdomen that can radiate to the back. Gastritis also can cause belching, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, a feeling of fullness, and a burning sensation in the upper abdomen.

Diagnosing Gastritis

Your doctor may suspect gastritis from the symptoms. However, because the symptoms of gastritis can be similar to those of other gastrointestinal illnesses, the only sure way to diagnose gastritis is by performing an endoscopy (see Chapter 2) to examine the stomach, and taking a biopsy of the stomach lining.

Treating Gastritis

Treatment for gastritis depends on the cause. If H pylori is the culprit, antibiotics will be prescribed—research suggests that eradicating H pylori in people with chronic gastritis may reverse the damage. If the cause of gastritis is prolonged use of NSAIDs, these medications should be discontinued. Similarly, if overuse of alcohol is to blame, the solution is to stop drinking.

For most types of gastritis, drugs to reduce stomach acid, such as H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors, will be prescribed. Since stomach acid irritates the inflamed tissue in the stomach, reducing acid production can promote healing.

Peptic Ulcer

A peptic ulcer (see Box 4-1, “Peptic Ulcer”) is a sore that forms in the lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer) or the first section of the small intestine (duodenal ulcer). Gastric ulcers can occur anywhere in the stomach, but are most common in the lower part (antrum). Duodenal ulcers occur in the first few inches of the small intestine (duodenum).

In the past, it was thought that ulcers were caused by stress, spicy foods, or an overabundance of stomach acid. It is now known that one of the main causes is infection with H pylori. Infection with H pylori, which usually occurs in childhood, doesn’t always cause ulcers—in fact, most people who carry H pylori in their gastrointestinal tracts don’t develop ulcers. Why this is so remains a mystery, but it may be related to the type of H pylori the person is infected with, use of certain medications, or age. Older adults are more likely to have ulcers, which may be due to a higher infection rate with H pylori, or because they use more NSAIDs.

H pylori bacteria have the ability to survive in the acidic environment of the stomach because they secrete enzymes that neutralize the acid. The bacteria can also burrow deep into the thick layer of mucus that coats the lining of the stomach, weakening the layer of mucus. This mucus is essential for protecting the layers of tissue underneath from being damaged by stomach acid. When the mucus layer is damaged, acid can irritate the sensitive tissue underneath, causing inflammation. Once inflammation occurs, continued irritation from acid and bacteria can lead to the formation of an ulcer.

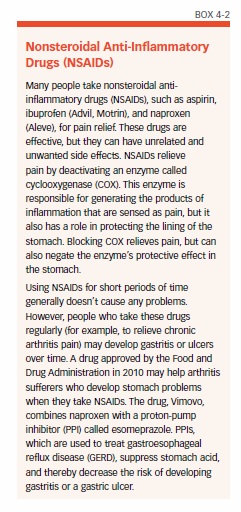

Long-term use of NSAIDs also can cause ulcers (see Box 4-2, “Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs [NSAIDs]”). People of any age can develop an ulcer from long-term use of NSAIDs, but it is more common in people over age 60. A warning sign that NSAID use may lead to an ulcer is upset stomach or heartburn after taking an NSAID. People with a history of ulcer, and those taking NSAIDs for long periods of time, are particularly at risk.

Peptic Ulcer Symptoms

The first sign of an ulcer is usually a burning sensation in the upper-to-middle abdomen that occurs within one to two hours after a meal. Other symptoms may include:

- Pain that feels like a dull, gnawing ache

- Pain that is intermittent or constant, lasting for days to weeks at a time before subsiding

- Pain that strikes in the middle of the night, or any other time that the stomach is empty

- Pain that decreases after you eat a meal

- Nausea and vomiting

- Weight loss

- Poor appetite

- Bloating

- Burping

Some symptoms warrant emergency medical attention, because they indicate that the ulcer has caused a hole (perforation) in the stomach or duodenal wall, broken a blood vessel, or blocked the path of food leaving the stomach and entering the intestine. If you experience any of the following symptoms, seek medical help right away:

- Sharp, sudden, persistent stomach pain

- Bloody or black stools

- Bloody vomit or vomit that looks like coffee grounds

Diagnosing a Peptic Ulcer

If you have any of the non-emergency symptoms of an ulcer, see a doctor to get diagnosed. Either an upper gastrointestinal (GI) series or an endoscopy will likely be ordered. If an ulcer is spotted, you will be tested for the presence of H pylori. The bacteria can be detected non-invasively, with breath or stool tests. If you have undergone an endoscopy, biopsy tissue will be tested for H pylori.

Treating a Peptic Ulcer

If the ulcer is caused by bacteria, medications are given to reduce stomach acid and kill the bacteria. This allows the ulcer to heal, and lowers the chance it will recur.

The treatment regimen will most likely involve two weeks of triple therapy: antibiotics to destroy the bacteria, a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) to reduce the production of stomach acid, and medications to protect the lining of the stomach from acid, such as sucralfate (Carafate) and bismuth, which also kills H pylori. This regimen is effective for 70 to 85 percent of patients.

An alternative is sequential therapy, which involves taking one or two drugs for a few days, followed by one or more different drugs.

If you have ulcers or ulcer complications and take NSAIDs, you may also need to take a PPI. You can get both with the drug Vimovo, which combines the PPI esomeprazole with the NSAID naproxen, or you may try to substitute acetaminophen (Tylenol) for the NSAID. If it does not relieve your pain, your doctor may suggest trying a different over-the-counter NSAID from the one causing the problem. You also can try to reduce the dose or the frequency with which you take the NSAID.

Gastroparesis

Gastroparesis—also known as delayed gastric emptying—is a condition in which the stomach fails to empty its contents properly, but no blockage is present (see Box 4-3, “Gastroparesis”). The condition occurs when nerves and muscles in the stomach fail to function properly. Sometimes the nerves don’t signal the muscles to contract, such as in diabetic neuropathy; sometimes the nerves work normally, but the muscles don’t respond. Possible reasons for this include:

- A disease that affects the nerves or muscles (such as multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, Guillain-Barré syndrome, or systemic scleroderma)

- Side effects from using narcotics

- Stomach virus after effects

- Damage to the vagus nerve during surgery

In more than one-third of patients, the cause for gastroparesis is never found.

Gastroparesis mainly affects young adult women, but about 20 percent of patients are children or men. People with diabetes, particularly when they are insulin-dependent, and those with acid reflux are at high risk for gastroparesis. The condition may occur daily, or in cycles. Needless to say, gastroparesis can be disabling, and the presence of chronic pain, nausea, and vomiting can cause depression, anxiety, and other psychological issues requiring help from a mental health professional.

Gastroparesis Symptoms

Symptoms include persistent nausea that worsens after eating. Patients usually vomit undigested food a couple hours after eating. Many patients report a burning, gnawing stomach pain that worsens after eating, and may become sharply painful.

Diagnosing Gastroparesis

Gastroparesis can be diagnosed with a gastric emptying breath test (GEBT) given in the doctor’s office. The night before the test, the patient eats a meal that includes scrambled eggs and the protein spirulina platensis, which has been enriched with carbon-13. Several measurements of carbon dioxide in the breath taken over a four-hour period the following day reveals how quickly the stomach is emptying. Patients with certain medical conditions, and those allergic to eggs, milk, wheat, or spirulina, can be tested with gastric scintigraphy, a type of X-ray that can help identify issues related to the emptying of the stomach.

Treating Gastroparesis

Nonsurgical treatments may be tried first. These can include dietary modifications (see Box 4-4, Dietary Changes That May Help Gastroparesis”), medications to stimulate gastric emptying, medications to prevent vomiting, medications to prevent intestinal spasms, and pain-relieving medication as needed. Some patients find biofeedback and relaxation techniques helpful.

Gastroparesis affects the intake of nutrients, so liquid vitamins and liquid nutritional supplements may be prescribed. Alternatively, a feeding tube or J tube may be placed directly into the small intestine, bypassing the stomach. In these severest cases, patients may require intravenous feeding.

In some patients, a gastric pacemaker may be placed laparoscopically. The device emits electrical impulses to stimulate the stomach muscles to contract. In some patients, this may be sufficient to move food through the stomach without symptoms.

Because the entire stomach is affected in gastroparesis, many stomach surgeries have not been effective. Even removal of the entire stomach may not solve chronic nausea. However, early results with a new minimally invasive procedure indicate it may normalize gastric emptying (see Box 4-5, “G-POEM Procedure Producing Positive Results”).

Stomach Cancer

More than 26,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with stomach cancer every year, and nearly 11,000 die from it. The cancer develops for unknown reasons and can be difficult to diagnose early, because its symptoms mimic those of other gastrointestinal diseases.

As with many cancers, people over age 55 are at increased risk. Men are almost twice as likely as women to get stomach cancer, and it is more common in African-Americans than in whites. Having the bacteria H pylori in the stomach may raise the risk, but prompt treatment to eradicate the bacteria can reduce the risk. A diet high in preserved meats (such as bacon and deli meats) and low in fruits and vegetables may contribute to stomach cancer. Conversely, a healthy diet loaded with fruits, vegetables, and whole grains and low in saturated fat may help decrease the risk of developing stomach cancer, and is particularly important for people infected with H pylori.

Stomach Cancer Symptoms

Stomach cancer often causes no symptoms at all. When symptoms are present, they are likely to be:

- Vomiting blood or bloody stools

- Pain or discomfort in the abdomen

- Nausea or vomiting

- Loss of appetite

- Weakness or fatigue

- Weight loss

If you experience any of these symptoms, see your doctor.

Diagnosing Stomach Cancer

One or more diagnostic tests may be needed, such as a fecal occult blood test, an upper GI series, and/or an endoscopy (see Chapter 2).

If cancer is suspected, the doctor will take a small sample of tissue (biopsy) from the wall of the stomach during an endoscopy. The tissue will be examined under a microscope to look for changes in the cells that would indicate cancer. If stomach cancer is diagnosed, the next step is to determine the stage of the cancer (see Box 4-6, “Stages of Stomach Cancer”), which indicates how far it has spread, if at all (stomach cancer can spread to nearby organs, such as the liver or pancreas). Staging of stomach cancer may be done with a computed tomography (CT) scan or ultrasound. Endoscopic ultrasound is also very good for this purpose.

Treating Stomach Cancer

Treatment for stomach cancer depends on a number of factors, including the size, location, and extent of the tumor, whether it has spread, and the patient’s general health. Options include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and targeted therapy (see Box 4-7, “Monoclonal Antibodies Target Stomach Cancer Cells”). According to the American Cancer Society, using two or more approaches produces the best outcomes.

Surgery is the most common treatment. If the cancer is in its early stages, the surgery may be performed endoscopically, using instruments that are inserted into the stomach via the throat.

If only part of the stomach needs to be removed, the remaining portion will connected to the esophagus or small intestine. If the cancer has spread throughout the stomach, the entire stomach may need to be removed (total gastrectomy), along with lymph nodes and other organs. The esophagus is then attached to the small intestine. After this surgery, patients must eat small amounts of food often, and some need a feeding tube for liquid nutrition in order to receive sufficient calories.

The post 4. Diseases and Disorders of the Stomach appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 4. Diseases and Disorders of the Stomach »

Powered by WPeMatico