3. Fruits and Vegetables

Color Your Plate

The quickest way to an appetizing, nutritious, and satisfying meal is including plenty of vibrantly colored fruits and vegetables (produce). Both the government’s MyPlate guide and Tufts’ MyPlate for Older Adults advise filling half of your plate with vegetables and fruits. These plant foods provide fiber and an array of vitamins and minerals. Additionally, like other plants, fruits and vegetables are loaded with natural compounds called phytochemicals (sometimes called phytonutrients). Phytochemicals give plants color, aroma, and flavor, and help protect the plant against diseases.

Research shows that when we eat phytochemicals, they act synergistically with each other and with vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients in foods, potentially maximizing the health benefits. Many phytochemicals are antioxidants, but they also may offer protection by stimulating the immune system, taming inflammation, or helping with DNA repair. Thousands of phytochemicals have already been identified. The greater the variety of vegetables and fruits you eat, the more diverse your intake of phytochemicals will be.

Produce is Packed With Benefits

Incorporating more fruits and vegetables into your diet will benefit your health in many ways. Following an eating pattern rich in vegetables and fruits (produce) may help lower blood pressure, reduce risks of heart attack and stroke, prevent some types of cancer, lower risks of eye and digestive problems, help with weight control, reduce risk of type 2 diabetes, and ultimately lengthen your life.

In a study that followed 65,000 adults for more than seven years, scientists found a strong association between fruit and vegetable intake and risk of dying (mortality) from any cause. Compared to people eating less than one daily serving, those eating the most vegetables and fruits (on average, seven or more daily servings) were 33 percent less likely to die of any cause during the follow-up period. Their risk of death from cardiovascular disease was 31 percent lower and risk of death from cancer was 25 percent lower. Although the greatest reduction in mortality was observed in adults eating seven or more daily servings of produce, even those eating one to three daily servings had a significantly lower mortality risk than those eating less than one.

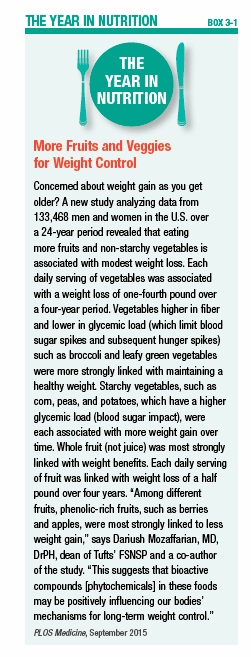

One way fruits and vegetables may reduce risk of disease and premature death is through their impact on body weight. Research suggests including plenty of fruits and non-starchy vegetables in your eating plan may help in weight control and weight loss (see Box 3-1, “More Fruits and Veggies for Weight Control”). The more fruits and vegetables you eat, the less room you have in your eating plan for higher-calorie or less healthy foods at meals and snacks. Additionally, the combination of fiber and water in fruits and vegetables takes up more space in your stomach, which may prevent you from overeating. The fiber and other indigestible materials in produce also provide food for the good bacteria that live in your gut. When your gut bacteria feast on the fiber and ferment it, they produce short-chain fatty acids. These fatty acids may help promote satiety, keep hunger in check, and reduce inflammation.

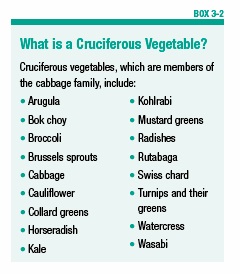

A lot of evidence suggests that cancers of the esophagus, pancreas, colon and rectum, breast (after menopause), endometrium, kidney, and gallbladder are related to excess body weight, so controlling weight by incorporating more fruits and vegetables may help reduce cancer risk. As mentioned previously, produce is also rich in phytochemicals, which may help protect against cancer, too. Cruciferous vegetables (see Box 3-2, “What is a Cruciferous Vegetable?” on page 29) have long had a reputation of being cancer fighters and are rich in phytochemicals, including ones called glucosinolates, which may help protect against the onset and progression of certain cancers. Carotenoids, another category of phytochemicals found in orange-colored foods such as carrots and sweet potatoes, and in dark leafy greens, have been linked with lower breast cancer risk.

Shortfalls are Common

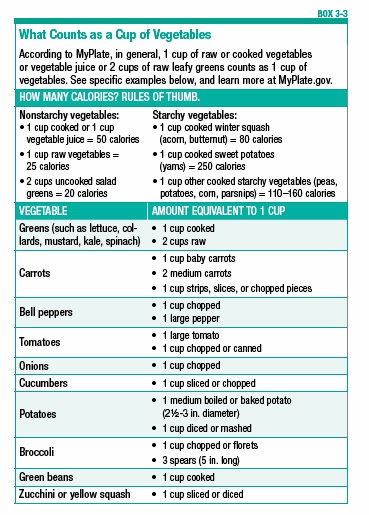

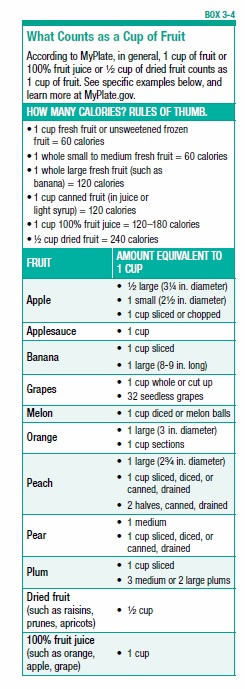

Adults should aim to eat at least 2 to 3 cups of vegetables and 1½ to 2 cups of fruit daily. A recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed that, overall, only 13 percent of people surveyed consumed at least the recommended amount of fruit, and less than nine percent of people ate the recommended amount of vegetables. A good rule of thumb is to eat a fruit, a vegetable, or both at each meal and snack. (See Box 3-3 on page 29 to see what counts as a cup of vegetables and Box 3-4 on page 30 to see what counts as a cup of fruit.)

In general, non-starchy vegetables, such as carrots, tomatoes, spinach, and broccoli, have fewer calories than starchy vegetables, which include potatoes, corn, peas, and acorn squash. So, it’s generally best to put more non-starchy vegetables on your plate than starchy vegetables. Non-starchy vegetables also contain fewer carbohydrates, which is important for people with diabetes to consider. For example, ½ cup of cooked broccoli has just 5 grams of carbohydrate and 27 calories, while ½ cup of corn has 15 grams of carbohydrate and 72 calories.

Practical Strategies to Improve Produce Intake

- Eat a variety of colors.

Consuming an assortment of differently colored fruits and vegetables will help ensure that you get a wider variety of nutrients. The color of a fruit or vegetable often hints at the nutrients, especially the phytochemicals, that it contains. For example, many orange fruits and vegetables, such as carrots, squash, apricots, and cantaloupe, provide the carotenoid beta-carotene, the precursor to vitamin A. Orange, yellow, and green vegetables, such as winter squash, leafy greens, and corn, contain other carotenoids, including lutein and zeaxanthin, which help protect your eyes; both nutrients have been linked with a reduced risk of macular degeneration and cataracts, conditions that can impair your vision.

Lycopene is a carotenoid present in some red fruits and vegetables, such as watermelon and tomatoes. Blue and purple produce, such as blueberries, blackberries, plums, and purple cabbage, contain anthocyanins, which are potent antioxidants. Even white and brown produce provide a unique profile of nutrients and phytochemicals. Mushrooms, for example, contain compounds called flavones and isoflavones, which have antioxidant and other health-boosting properties. Eating a salad that contains a variety of colorful vegetables every day is one easy way to experiment with different types of produce.

- Move beyond potatoes.

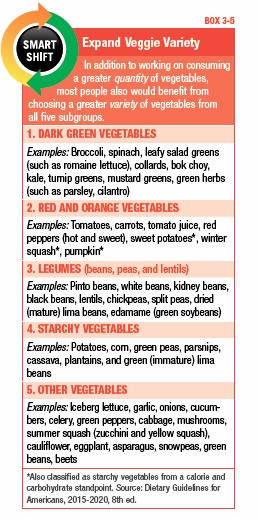

Potatoes are the most commonly eaten vegetable, and these are most often consumed in highly processed forms, such as French fries and potato chips. When choosing vegetables, make a greater effort to eat from the different vegetable subgroups (see Box 3-5, “Expand Veggie Variety,” on page 31), and opt for vegetables in their whole, natural form rather than highly processed forms. When you do eat potatoes, avoid removing the skin, and skip the traditional toppings that are high in saturated fat, such as butter, cheese, and sour cream. Instead, top them with a drizzle of extra-virgin olive oil, beans, salsa, herbs, or sautéed vegetables.

- Think outside the fruit bowl.

Even with fruits, people tend to reach for familiar favorites, such as bananas, apples, and oranges. Challenge yourself to get a greater variety of fruits by buying at least one different kind of fruit on each trip to the grocery store. Tropical fruits have become much more common in supermarkets and can be a nutritious way to change up your fruit routine. Consider trying:

Guava: Thought of as the “apple of the tropics,” this fruit is typically round or pear-shaped. Depending on the variety, guavas may have a yellow, green, or pink skin, with internal flesh that ranges from white to pinkish-red. One cup of guava has more than six times the daily value of vitamin C and 20 percent of the daily value of potassium. Guavas are ripe when they give to gentle pressure. To eat guava, cut it in half crosswise and scoop out the flesh with a spoon. Or, dice guava and add it to a fruit salad.

Kiwifruit: The bright-green flesh of this fuzzy-skinned fruit contains more vitamin C per cup than an orange. Although the skin is edible, most people prefer to peel it. Kiwifruit is ripe when it gives slightly to gentle pressure. If you’re adding it to a fruit salad or using it as a garnish, slice it shortly before serving because enzymes released by slicing the fruit cause the flesh to soften or become mushy over time (and also prevent gelatin from setting).

Mango: If you haven’t yet had one of the world’s most popular fruits, make it a point to try mangos soon. Its yellow flesh is a clue that it’s high in vitamin A (primarily in the form of beta-carotene) and zeaxanthin, both associated with eye health. Don’t judge a mango by its exterior skin color—red does not mean the fruit is ripe, and yellow and green don’t mean the fruit is unripe. Similar to other tropical fruits, a mango is ripe when it gives slightly to gentle pressure. Mangos have a long seed in the center, so you can’t cut it completely in half, rather, you have to work around the seed when cutting the fruit. Try mangos by themselves or in smoothies, salads, and salsas.

- Select whole fruit more often than juice.

If you’ve heard that you should avoid fruit because it’s mostly sugar, have no fear; fruit, especially whole fruit, has much to offer in the way of valuable nutrients, including fiber, potassium, magnesium, folate, and vitamins A, C, and K. Juice should be approached more cautiously. Though a morning glass of OJ is refreshing, it short-changes you in fiber. A cup of juice has less than a gram of fiber, but a whole medium orange provides about three grams. The whole fruit saves you extra calories, too. You’ll likely feel fuller with the 62 calories from the whole orange than you will from the 110 calories in the cup of juice. This doesn’t mean you should stop drinking 100-percent fruit juice, but, if you drink a lot of it, swap some for whole fruit. While the consumption of whole, unprocessed fruit has been linked with improved weight loss and weight control, fruit juice has not. Additionally, research suggests that eating three servings of whole fruit in place of three servings of juice per week could reduce diabetes risk by five percent.

- Stock up on frozen and canned fruits and vegetables.

In the winter and early spring, you may have limited choices for fresh produce. However, frozen fruits and vegetables are excellent options and are just as nutritious (if not more so, due to quick processing after harvest) as fresh produce sold in the supermarket. Canned varieties can be good options, too, but they may be lower in certain nutrients because heat-sensitive vitamins are decreased by the heat used during the canning process, and some of the water-soluble vitamins leach into the canning liquid. When selecting frozen or canned vegetables or fruits, look for ones that contain no sauces, salt, or added sugars.

- Maximize nutrient retention with smart cooking methods.

By cooking with minimal amounts of liquid and keeping cooking times short, you’ll get the most nutrients from your fruits and vegetables. Steaming is a very healthful cooking method and reduces nutrient loss. Roasting also is a good option because it uses no water, so there is no chance that certain water-soluble vitamins, such as vitamin C, can leach into the cooking water.

If you have the time, peel and chop your fruits and vegetables just before eating, rather than hours or days in advance, to save on nutrient losses. However, in a hectic life, this isn’t always practical. The most important thing is to eat plenty of fruits and vegetables and to eat a variety of them.

- Eat fruits and vegetables throughout the day.

It would be impossible to eat the recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables if you waited until dinner to get started, yet many people do just that. Use these tips to help you get delicious, disease-fighting fruits and vegetables every time you eat.

- Grill or bake fruit for dessert or for a sweet side dish.

- Eat salad frequently, whether as a main dish or appetizer. Think beyond basic iceberg lettuce, which is a nutritional lightweight, and go for darker greens. The vitamin K found in dark, leafy greens such as kale and spinach may even help you move around better as you age (see Box 3-6, “Vitamin K May Support Mobility”).

- Top leafy salads with chopped avocado rather than bottled salad dressing. The healthy fat in avocados can help you absorb carotenoids in your salad. (For more about avocados, see Box 3-7, “Fruit of the Year: Avocado,” on page 33.)

- Stuff an omelet with vegetables, such as mushrooms, chopped broccoli, tomatoes, and onions.

- Add shredded carrots or zucchini to ground meat before shaping into a meatloaf or meatballs.

- Fill sandwiches with all types of vegetables, including bell peppers, mushrooms, cucumbers, tomatoes, avocado, and spinach.

- Dip raw veggies into hummus or salsa.

- Add diced cauliflower, broccoli, or tomatoes to casseroles such as lasagna and macaroni and cheese.

- Puree cooked cauliflower to mix with mashed potatoes.

- Stir pureed pumpkin or winter squash into chili or tomato-based casseroles.

- Keep frozen berries on hand to mix into low-fat yogurt.

- Add frozen fruit, such as diced peaches or wild blueberries, to homemade muffin batter.

Smart Smoothies

Smoothies, which are blended drinks typically made with fruits, vegetables, and a liquid, have become a popular way of consuming produce, but are they a smart choice? It largely depends on portion control and how they’re made. In some cases, commercially-made smoothies are too high in calories and sugar, and some people may find it less satisfying (filling) to drink their produce than to chew it, which could interfere with weight-control efforts. To make a healthy, calorie-controlled smoothie, follow this formula (which makes about 16 ounces):

- Choose 1 cup (packed) leafy greens. Try fresh baby spinach, kale, Swiss chard, or collard greens (stalks removed).

- Add 1 cup liquid. Water and unsweetened green tea are calorie-free options. Or, try low-fat milk, an unsweetened milk substitute such as fortified soy milk or almond milk, or coconut water. Skip fruit juice, which is more concentrated in calories.

- Choose 1 cup fruit, preferably unsweetened frozen or fresh fruit. Try a combination of two or three varieties, such as banana, berries, pineapple, melon, mango, pear, peach, or kiwifruit.

- Boost protein and/or healthy fat (both will also increase calories), if desired. To increase protein, add one to four tablespoons silken tofu, nonfat powdered milk, plain Greek yogurt, or pumpkin seeds. To increase healthy fat, add one to two tablespoons nuts, natural nut butter, avocado, or ground flaxseed.

- Add optional flavorings. Depending on the fruit you use to make the smoothie, you may not need to add a sweetener, but, if necessary, add a bit of honey or chopped dates. Vanilla extract, peppermint extract, cinnamon, or fresh mint also make nice flavorings and are essentially calorie-free.

If you’re using a basic kitchen blender rather than a high-speed blender (such as Blendtec or Vitamix) to make the smoothie, chop the greens finely, and then add the liquid and blend until smooth before adding finely chopped fruit and other ingredients. Once you’ve blended all of the ingredients together, taste and make adjustments as needed. If the smoothie is too thick, add a little more liquid. If the smoothie is too thin, add more of a thick ingredient, such as yogurt. Using some frozen ingredients, such as frozen fruit or a few ice cubes, will help chill the smoothie. To help protect your teeth from the sugar and acidity of the smoothie, use a straw to drink it and avoiding swishing the fluid around in your mouth.

The post 3. Fruits and Vegetables appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 3. Fruits and Vegetables »

Powered by WPeMatico