2. Eating To Beat Disease

When you have a chronic health condition or are at increased risk of a chronic disease, such as obesity, heart disease, diabetes, or celiac disease, it’s natural to focus on foods you should limit or avoid. However, you’ll likely find eating more enjoyable if you shift your attention to substituting tasty, healthy foods that can help you manage your disease rather than dwelling on the foods you should pass up. This chapter highlights science-based dietary approaches for managing common chronic health conditions. Later chapters provide more details on shifting your eating pattern to focus on healthy, nutrient-rich foods. If you or someone you care for need specific guidance on eating to prevent or manage a health condition, consult with a registered dietitian nutritionist, your doctor, and other members of your healthcare team.

Eating for Weight Control

If you’re overweight, even a small amount of weight loss can have big benefits. For example, losing just five to 10 percent of your body weight can result in more energy, a better mood, and improved health. In some studies where participants experienced moderate weight loss of five percent or even less, they reported improvements in physical functioning, vitality, and mental health. Modest weight loss also has been found to reduce osteoarthritis knee pain, decrease urinary incontinence, lower the risk of type 2 diabetes, and improve cholesterol and blood pressure levels.

Manage Your Appetite

Many different dietary strategies can help you lose weight, but a key to long-term success is keeping hunger and cravings under control. One hormone, ghrelin, is the primary driver of hunger. To help keep it in check, try to maintain a consistent meal and snack schedule. Another hormone, leptin, helps signal the brain that you’re full, which suppresses your appetite. We need to pay attention to our bodies and tune in to these signals. Unfortunately, once we’ve gained weight and become obese, our bodies become resistant to the effects of leptin, so we feel hungrier. The good news is that there are ways to reduce leptin resistance, including getting regular exercise and eating foods rich in anti-inflammatory antioxidants and omega-3 fats, such as colorful fruits and vegetables and salmon. Getting enough sleep (generally 7 to 8 hours) also can help in maintaining desirable leptin and ghrelin levels. Eating foods with low energy density (fewer calories per bite) also may help dampen ghrelin levels. This strategy is described in the next section.

Feel Full on Fewer Calories

If someone served you foods that took up only a small space on your plate, such as half of a turkey sandwich or a single scoop of ice cream, you might think: “That won’t fill me up” or “I definitely want more.” What you’re responding to is the skimpy portion rather than the calories in the food, even though the calories may be more than enough.

Numerous studies have found that people tend to base their sense of fullness on the amount or volume of food they eat rather than on how many calories they’ve consumed. One way to eat a satisfying meal while keeping calories in check is to eat foods that take up a lot of space on your plate and in your stomach but that don’t have many calories. In other words, opt for foods with fewer calories per bite. One example is a big, leafy green salad (provided it’s not drenched in salad dressing). Salads take up a lot of space on your plate, require a lot of chewing, and stretch your stomach, which signals your brain that you’ve eaten a satisfying amount.

Even if you don’t know the calorie count of a dish, you can often guess whether it’s packed with calories based on what’s in it. Foods that are high in water, fiber, and/or air, such as non-starchy vegetables, broth-based vegetable soups, fruits, low-fat dairy products, air-popped popcorn, and minimally processed whole grains, pack fewer calories per bite. Foods that are lower in water or higher in fat and/or sugar, such as dry snack foods, fatty meats, rich sauces or dressings, fried foods, and decadent desserts are generally calorie-dense, packing in more calories, but often fewer nutrients, per bite. (See more examples in Box 2-1, “Choosing Foods With Fewer Calories Per Bite.”) Energy-dense foods aren’t necessarily off-limits for the calorie-conscious, but you do need to be careful of portion sizes.

Mindful Eating

If you’ve eaten a meal or snack and can hardly remember what it tasted like, chances are you were multi-tasking or distracted in some way. Avoid eating in front of the computer, while driving, when you’re talking on the phone, or while watching TV, because you are missing out on enjoying your food, and you may have no idea how much you’re consuming. Being distracted can lead to overeating. Other forms of distraction that may lead you to overeat are emotions such as stress, sorrow, anxiety, and even boredom. When you’re eating, take time to notice the taste, texture, and aroma of your food. This can help you stop eating when you are full. Also, be mindful that you only need to provide fuel for your body until the next meal.

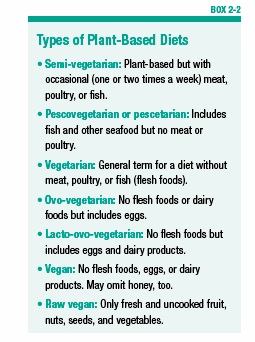

Vegetarian and Vegan Diets

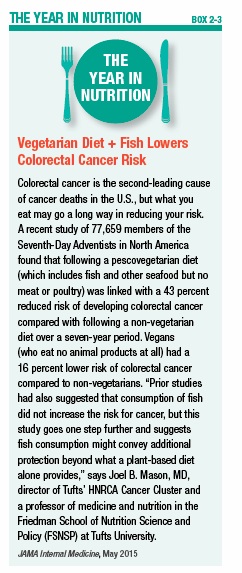

Many people are trying to eat more plant foods and less meat, and some have decided to follow a vegetarian diet (see Box 2-2, “Types of Plant-Based Diets,” on page 14). People generally choose to be a vegetarian for health, environmental, or ethical reasons. Recently, scientists published the first systematic review of 96 (86 cross-sectional and 10 prospective) observational studies on vegetarian and vegan diets and certain health outcomes. In their analysis of 10 prospective cohorts (groups of people followed over time), eating a vegetarian diet for four years or more was linked with a 25 percent reduced risk of ischemic heart disease (reduced blood supply to the heart) and an eight percent reduced risk of cancer, overall. Among those following a vegan diet, a 15 percent reduced risk of cancer was found. Analysis of the cross-sectional data (which is collected at one point in time) showed that total cholesterol, LDL (“bad”) cholesterol, blood sugar levels, and body mass index (BMI) were lower in vegetarians and vegans than in omnivores (who eat both animal and plant foods). Other research suggests vegetarian diets may help reduce colorectal cancer risk (see Box 2-3, “Vegetarian Diet + Fish Lowers Colorectal Cancer Risk”).

To experience the health benefits of a vegetarian diet, you need to make healthful food choices overall, not simply avoid meat. Although French fries, doughnuts, and soft drinks may be made with vegetarian ingredients, they’re far from healthy. However, if you put some thought and planning into your vegetarian diet and include a variety of whole and fortified foods, it can be nutritionally adequate (see Box 2-4, “Nutrients of Concern for Vegans,” on page 16).

Protein deficiency has often been a concern of vegans and vegetarians who omit eggs and/or dairy products, but it is possible to get adequate protein if you are consuming enough calories from whole, plant-based foods. Numerous plant foods supply protein, especially legumes and some nuts. Although plant foods do contain all essential amino acids (the protein “building blocks” needed by the body), they typically have smaller amounts of certain essential amino acids. At one time, it was thought that people who excluded animal proteins should combine plant foods containing complementary amino acids at the same meal, such as tortillas with beans, to help ensure they’d get enough essential amino acids. However, it’s now known that eating a variety of plant-based proteins throughout the day provides your body with enough essential amino acids.

Soy products are a popular protein source among non-meat eaters, as soy is a unique plant food that contains adequate amounts of all essential amino acids. However, avoid regularly replacing meat with soy-based, overly processed “fake” meats, such as vegetarian burgers, hot dogs, and cold cuts—the isolated soy proteins they contain may not be as healthful as less processed soy products, such as tofu and tempeh. In addition, these meat substitutes often are laden with salt, artificial colors and flavors, and other additives.

Heart-Smart Eating

Dietary patterns aimed at supporting cardiovascular health help address disease risk factors such as high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol, inflammation, and obesity. Although many variations of heart-smart diets are promoted by health organizations, two of the most popular, science-backed approaches—the Mediterranean-style diet and the DASH diet—are described here. Both of these diets consist of whole and minimally processed foods that contain specific nutrients known to promote better cardiovascular health. They also restrict sugar and sodium intake and limit calories from trans fat and saturated fat.

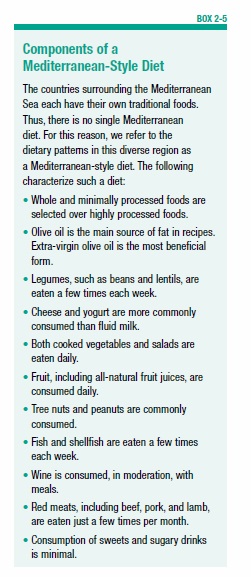

A Mediterranean-Style Diet

The Mediterranean-style eating pattern has received attention and praise for both its flavor and healthfulness. This diet is rich in fruits, vegetables, beans, nuts, and olive oil, along with frequent fish meals and few meals with red meat. There is plenty of variety with this eating style; see Box 2-5, “Components of a Mediterranean-Style Diet,” for a more detailed description of a Mediterranean-style diet. The Mediterranean-style diet does not restrict beneficial monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, so you can still enjoy avocados, nut butters, and olive oil.

Mediterranean-style diets have long been associated with improved cardiovascular health and reduced risk of stroke. When researchers reviewed 50 studies conducted in the US, Australia, and Greece, they found a link between a Mediterranean-style diet and protection against metabolic syndrome, a cluster of health problems including high blood pressure, elevated blood sugar, abnormal blood cholesterol and triglycerides, and excess abdominal fat. In addition, a Mediterranean-style diet has been linked with a lower incidence of specific heart conditions, including sudden cardiac death (triggered by a dangerously fast heartbeat).

Newer research links the Mediterranean-style diet with protection against age-related macular degeneration, which is the leading cause of blindness in older Americans. Furthermore, preliminary research suggests the Mediterranean diet may help reduce the risk of breast cancer. Certain dietary components may be especially beneficial. In a five-year study of Spanish women, following a Mediterranean-style diet that emphasized olive oil (which was eaten in place of animal fats, such as from meat and butter) was associated with a 68 percent lower risk of breast cancer compared to following a standard diet that simply advised cutting back on total fat intake. Extra-virgin olive oil, which is much higher in polyphenols than refined olive oil, may be especially protective.

The DASH Diet

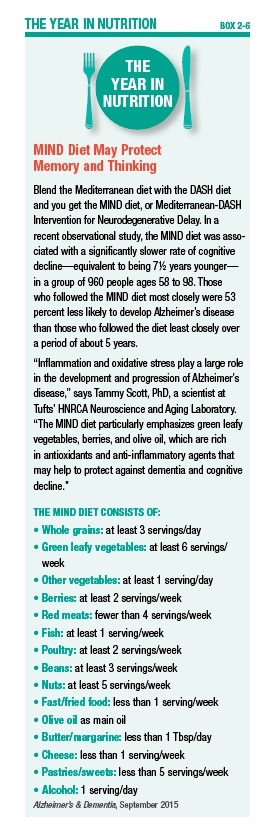

The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet is a healthful eating pattern that has been named the best overall diet in America for the past six years by U.S. News and World Report, based on rankings by a panel of health and nutrition experts. Additionally, the MIND diet, a new hybrid of the DASH and Mediterranean-style diets that focuses on foods that support brain health, was ranked second in overall healthfulness (see Box 2-6, “MIND Diet May Protect Memory and Thinking”).

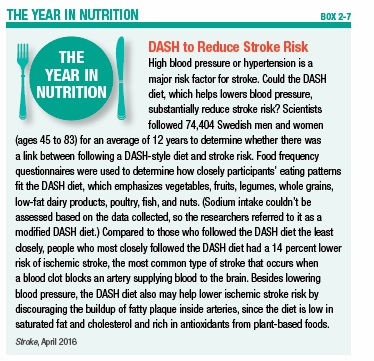

Research funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) showed that the DASH eating pattern, which emphasizes fruits, vegetables, and low-fat or nonfat dairy products, lowers blood pressure as well as a single medication might. High blood pressure (hypertension) is a major risk factor for stroke, and new research has linked the DASH diet with a reduced risk of stroke (see Box 2-7, “DASH to Reduce Stroke,” on page 19). Other research suggests that following a DASH diet may reduce the risk of some acute cardiovascular events, including heart failure. A DASH dietary pattern also may help protect against osteoporosis, kidney stones, diabetes, and some cancers.

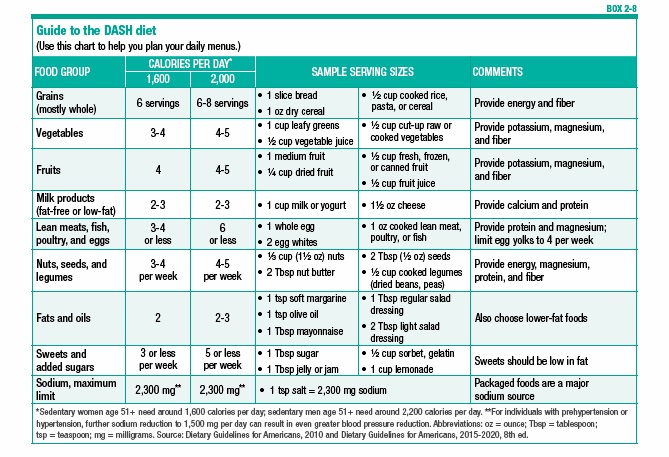

Besides a focus on fresh produce and low-fat milk products, DASH also includes whole grains, nuts, fish, poultry, oils, and soft spreads or liquid or tub margarines low in saturated fat. The foods emphasized in this diet are rich in nutrients that help to lower blood pressure, including potassium, magnesium, and calcium. For more information about the DASH diet, including examples of serving sizes for various foods, see Box 2-8, “Guide to the DASH Diet,” on page 19.

Carbohydrates, Blood Sugar, and Health

Carbohydrates are found mainly in grains, legumes, fruits, vegetables, dairy products, and sweets. Carbohydrates are the main nutrients that impact blood sugar (blood glucose), and they’re a key consideration in managing diabetes. Your carbohydrate choices also may impact appetite, weight control, and certain chronic disease risk factors.

The Glycemic Index and Blood Sugar

The glycemic index (GI) is a relative ranking of carbohydrate-containing foods on a scale from 0 to 100 according to how they affect blood sugar levels after eating. Only carbohydrate-containing foods have a GI; meats and fats do not. Foods with a high GI are rapidly digested and absorbed, producing a rapid rise in blood sugar. Foods with a low GI are more slowly digested and absorbed, producing a more gradual rise in blood sugar. Pure sugar has a GI of 100. Low-GI foods have a GI value of 55 or lower, medium-GI foods have a GI between 55 and 69, and high-GI foods have a GI of 70 or higher. The GI of a food is the same regardless of how much is eaten.

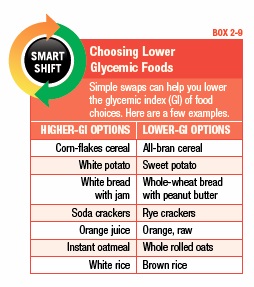

Although the GI may be useful in making food choices when you’re trying to improve blood sugar control, applying the GI concept to your everyday eating pattern can be more complicated than it might appear—and the GI shouldn’t be your only consideration when choosing carbohydrates. For example, pound cake has a GI of 38, but that doesn’t mean it’s a more nutritious choice than a banana, which has a GI of 62. Pound cake doesn’t provide the potassium and fiber that a banana has, plus pound cake is typically high in fat and calories. The reason pound cake has a lower GI is because the fat in it slows digestion, so the carbohydrate in it will be broken down more slowly, and glucose will enter your bloodstream more gradually. For examples of smart ways to lower the GI of your food choices, see Box 2-9, “Choosing Lower Glycemic Foods.”

Other Uses of the Glycemic Index

Short-term studies suggest that diets that emphasize foods with a lower GI may not only help control blood sugar but also help control appetite. High-GI foods have been linked with increased appetite and greater calorie intake in single-meal studies. Susan B. Roberts, PhD, director of Tufts’ HNRCA Energy Metabolism Laboratory, says that low-GI foods may be better at keeping hunger at bay in some people because the more stable blood sugar produced by these foods tells your brain that it isn’t time yet to eat again. Research by Roberts and several other scientists worldwide suggests that choosing lower-GI foods promotes weight loss and prevents weight regain for about half of the population.

A recent scientific review also concluded that following a low-GI diet may help reduce markers of inflammation and reduce the occurrence of high cholesterol and high blood pressure, which are risk factors for heart disease.

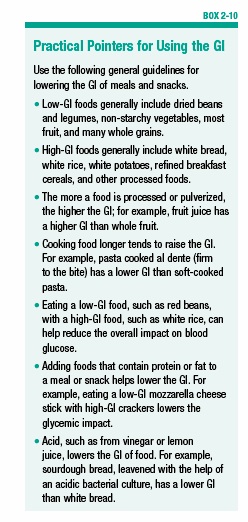

If you find the GI confusing or cumbersome, you don’t have to include it in your considerations when making food choices. In a nutshell, most low-GI foods are whole foods, including fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and most high-GI foods are processed foods made with refined grains (white flour) and/or added refined sweeteners—foods you’d be wise to avoid regardless of their GI index. For further details, see Box 2-10, “Practical Pointers for Using the GI.”

Food Sensitivities and Intolerances

Although a person can potentially develop an adverse response to any ingested substance, one of the most common culprits is gluten. Gluten is a protein found in wheat, rye, and barley that makes dough stretchy. Giving up every crumb of gluten is essential for the estimated one percent of the population with celiac disease, a genetically-based disorder that tends to run in families.

Celiac Disease

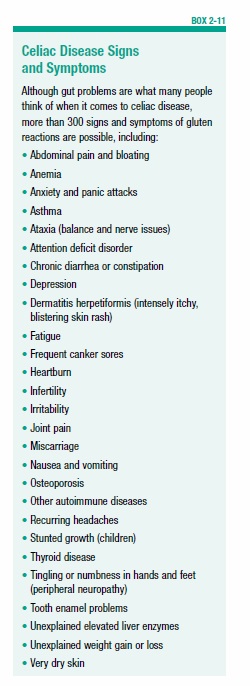

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disease in which the immune system attacks the body’s own tissues, such as the lining of the small intestine, when gluten is consumed. Attacks on the small intestine’s villi, which are fingerlike projections that help absorb nutrients from food, can lead to malnutrition and other problems. Some people may experience digestive issues, such as gas and diarrhea, when they eat gluten, while others might have unexplained depression, fatigue, headaches, skin issues, or other problems. The most common symptom of celiac disease that shows up in doctors’ offices is iron-deficiency anemia and related fatigue (see Box 2-11, “Celiac Disease Signs and Symptoms” for other symptoms). Celiac disease can affect any part of the body, though.

You should be tested for celiac disease before going gluten-free because you need to be currently consuming gluten for medical testing to be accurate. Testing typically starts with a simple antibody blood test, which may be followed by more in-depth tests, if needed. Although some people skip testing, it’s important to know whether you have celiac disease so you can be properly monitored and receive insurance coverage. Also, being certain of your diagnosis helps reinforce how important it is to stick to the required diet.

The treatment for celiac disease is a strict, lifelong gluten-free diet, including avoiding cross-contamination from bread crumbs in toasters, butter dishes, and cooking utensils and pans, as well as avoiding gluten in medications and supplements. An increasing number of tasty, gluten-free options are available in supermarkets and restaurants, including pizza, cookies, and packaged snacks. Although these options make life simpler, an overreliance on gluten-free goodies could lead your eating habits astray. These processed foods often contain ingredients with little nutritional value and can displace healthful, naturally gluten-free foods, such as fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, lean meat, fish, poultry, and minimally processed, gluten-free whole grains, including teff, quinoa, and brown rice. If you’re newly diagnosed, ask your doctor for a referral to a registered dietitian nutritionist who is knowledgeable about gluten-free diets.

Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

People whose tests don’t show celiac disease but who have celiac-like symptoms when they consume gluten may be diagnosed with non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) after also ruling out a wheat allergy. The dietary remedy is the same as for celiac disease—a gluten-free diet. It’s uncertain how many people NCGS affects, but available estimates range from 0.6 percent to 6 percent of the population. Unfortunately, medical understanding of NCGS is about where celiac disease was 40 years ago, and, currently, there isn’t a medical test that can reliably detect it (although medical researchers are working to identify one). In some cases, poor tolerance of wheat products may instead be due to bacterial fermentation of certain short-chain carbohydrates called fructans, resulting in bloating and pain (see the next section for details).

Fermentable Carbohydrates and Your Gut

Some natural sugars and fibers found in milk products, fruits, certain vegetables, wheat, and legumes may be poorly digested or poorly absorbed in the small intestine, which can result in digestive discomfort. These carbohydrates are called FODMAPs (which stands for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides And Polyols). When these FODMAPs move to the large intestine, bacteria ferment the sugars in the foods. This fermentation results in gas, which may be accompanied by abdominal bloating and pain, as well as nausea, diarrhea, and/or constipation. At high intakes, FODMAPs can bother anyone, but some people are particularly susceptible to the digestive side effects of these carbohydrates. Gastroenterologists (doctors who specialize in digestive health) may order hydrogen breath tests or other tests to determine your ability to digest certain FODMAPs, including fructose and lactose.

Lactose Intolerance

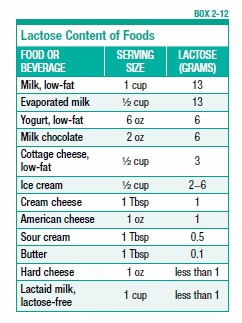

Lactose, which is a FODMAP (see previous section), is the naturally-occurring sugar in cow’s milk. Many adults don’t produce enough lactase, the enzyme in the small intestine that breaks down lactose. Lactose intolerance can result in uncomfortable gut symptoms, which typically begin within 30 minutes to two hours of consuming dairy products. Different dairy products have varying amounts of lactose, so tolerance may differ from product to product (see Box 2-12, “Lactose Content of Foods”). For some people, simply reducing the portion sizes of milk products or consuming them as part of a meal with other foods can help, while other people may be intolerant even to small amounts. Some people take lactase enzyme pills to help digest dairy products. Another option is to purchase dairy alternatives that are fortified with calcium and vitamin D, such as some soy, rice, almond, and coconut-based dairy substitutes. You can read more about these dairy-free options in Chapter 8.

Other FODMAPs

Some people are not able to easily absorb excess fructose, a naturally-occurring sugar in fruit, honey, and some vegetables. That doesn’t mean all of these foods are problematic. Individual digestive tolerance varies widely, and tolerance of fructose partly depends on whether the food contains excess fructose in comparison to glucose, another simple sugar, which helps escort fructose across the intestinal wall.

Fructans (chains of fructose) are another potentially problematic FODMAP; they are found in wheat, certain vegetables, such as garlic and onions, and in a type of fiber called inulin, which is sometimes added to packaged foods. Indigestible sugars called galactans, found in dried beans, peas, and soy, can be problematic for some people, as can polyols, a type of sugar found in fruits such as peaches, plums, and watermelon, as well as sweeteners such as sorbitol and xylitol. If you seem to have significant digestive issues when you eat FODMAP foods, consult a gastroenterologist and ask for a referral to a registered dietitian nutritionist who is knowledgeable about the low-FODMAP diet. After a couple of months on such a diet, you can then reintroduce each type of FODMAP, one at a time, to determine your tolerance.

Supplementing Your Diet

In general, meeting your vitamin and mineral needs is possible when you follow a healthy eating pattern. Getting your nutrients from foods can also save you the time and expense of taking nutritional supplements. Dietary supplements are one option people turn to when they’re trying to fill nutritional gaps in their eating plan or when they’re seeking a specific health benefit. Among the most common product options are vitamin, mineral, and herbal supplements. Such supplements come in many forms, such as tablets, capsules, powders, and liquids.

Unlike medications, which must be proven safe and effective before the FDA allows them to be marketed, the FDA does not approve dietary supplements before they can be sold. It’s the responsibility of manufacturers to ensure supplements are safe before they’re marketed; the FDA must show a supplement is unsafe before restricting its sale.

Some dietary supplements may be harmful when taken in high amounts, for a long time, or in combination with other supplements or certain medications. For example, supplements containing vitamin K, which is involved in blood clotting, interact with anticoagulant drugs, such as warfarin (Coumadin). If you take warfarin, it’s very important to keep your vitamin K intake consistent from day to day; however, it is a myth that people taking warfarin should not consume any vitamin K, which is found in nutritious foods such as spinach, kale, and other leafy greens. Other supplements can have undesirable effects before, during, or after surgery. For instance, uncontrollable bleeding is a potential side effect of taking vitamin E, garlic, ginkgo biloba, or ginseng supplements in the two weeks before surgery.

The FDA advises that you consult with a healthcare professional before using any dietary supplement, and always tell your healthcare provider about all supplements you use if you’ll be undergoing surgery. Some general guidance on supplement use is provided here.

Vitamin and Mineral Supplements

If you must follow special dietary restrictions, such as avoiding gluten or dairy products, you may be at a greater risk of nutritional deficiency if you don’t address the gaps with other dietary strategies. Additionally, as you grow older, your calorie needs decline, yet vitamin and mineral needs generally remain the same or, in some cases, are increased. Older adults are more likely to fall short on certain nutrients, such as calcium, vitamin D, vitamin B12, and protein. Your doctor can easily test for some nutrient deficiencies, such as vitamin D, while other deficiencies aren’t as easily detected. In some cases, physical signs of deficiency may appear, such as slow healing of wounds, which could signal a deficiency of vitamin C and/or zinc.

If you’re falling short on certain vitamins and minerals or have increased needs, taking a nutritional supplement can help. A multivitamin/mineral supplement that provides around 100 percent of the daily value of most nutrients may be adequate for this purpose. However, if your doctor has identified a specific deficiency, you may need to take individual supplements at higher doses, such as for vitamins D or B12, either temporarily or long term. If you have particular nutritional goals, such as supporting eye health or memory, more targeted supplements can be recommended by your healthcare providers.

Herbal Supplements

Beyond vitamin and mineral supplements, another popular category of dietary supplements is herbal formulas, such as echinacea and ginkgo biloba. Although you may find various product claims as to how such supplements may help you, many of these products have limited research backing their purported benefits and may not be worth the money. For example, echinacea capsules are touted to reduce the common cold, and some studies suggest they may help modestly reduce cold symptoms if you take them at the first sign of cold symptoms. However, other studies don’t show any benefit of taking echinacea supplements for colds. Similarly, ginkgo biloba is often promoted as a memory aid, but most scientific evidence fails to show that taking ginkgo supplements improves memory or attention in older people with normal mental function or in those with age-related memory loss. Before you buy such supplements, ask a qualified health professional to help you determine if there’s good research evidence supporting particular benefits.

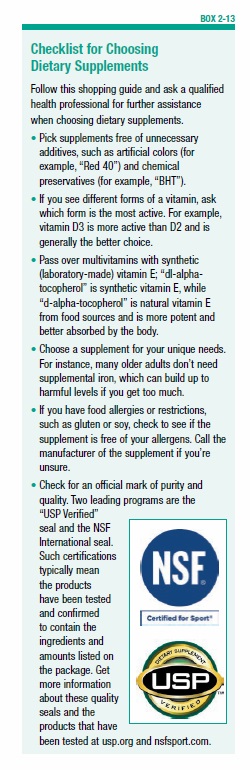

It’s also important to consider the quality of any supplement before you buy it. Unfortunately, the quality of dietary supplements varies greatly. An investigation by the New York State attorney general’s office found that over-the-counter herbal supplements sold at discount stores and drug stores often didn’t contain the ingredients claimed on the ingredient list. In some cases, the supplements contained unlisted fillers, including wheat and legumes, which are allergens for some people. For guidance on buying supplements, see Box 2-13, “Checklist for Choosing Dietary Supplements,” on page 24.

Liquid Meal Replacement Supplements

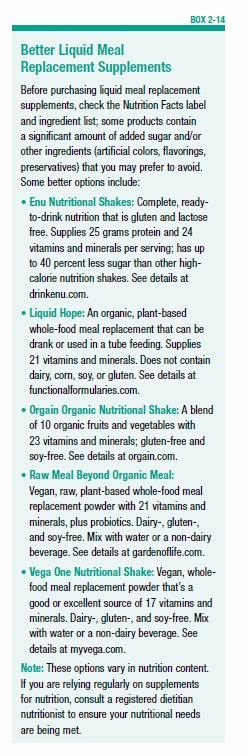

Whole, natural foods are, by far, the best source of nutrition. However, for those with a poor appetite (such as the elderly in long-term care facilities or those undergoing cancer treatment) who aren’t eating enough, and, as a result, are falling short on protein, calories, and other essential nutrients, another option is liquid nutritional shakes. Beware of popular commercial products that contain a lot of added sugars and artificial ingredients (see Box 2-14, “Better Liquid Meal Replacement Supplements”). The American Academy of Geriatrics advises against using typical sugary liquid supplements, even for most older adults suffering from unintentional weight loss. Whenever possible, it’s best to improve nutritional intake with unprocessed foods, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and seeds, which are ultimately the most nutrient-dense and healthful.

Alcohol and Nutrition

Research has shown that moderate alcohol intake may help lower the risk for heart disease. However, no doctor or health expert would suggest starting to drink alcohol solely for this reason, given the substantial risks associated with excessive drinking and addiction. Excessive alcohol intake increases a person’s risk of developing high blood pressure, liver disease, osteoporosis, certain cancers, heart disease, and stroke, as well as many other chronic health problems.

Nutrition may not be an emphasis at alcohol treatment centers, but it should be. For example, hypoglycemia or low blood sugar is a common nutritional problem in alcoholics and can contribute to cravings for alcohol and sugar. Eating five or six smaller meals and snacks a day can help keep blood sugar levels in the normal range. It’s best to choose meals and snacks that provide a mix of lean protein and complex carbohydrates from whole grains and vegetables to help keep blood sugar levels steady. For instance, carrots with hummus or apples spread with natural nut butter are good, balanced snacks.

People with alcohol dependence are prone to deficiencies of B vitamins, such as thiamin and folate, partly due to poor diet but also due to alcohol’s effects on the metabolism of vitamins. Such deficiencies can ultimately impact cravings for alcohol, increase irritability and aggressiveness, and lower impulse control. Additionally, alcohol increases excretion of minerals, including magnesium, calcium, and zinc. Someone seeking an alcohol treatment program should inquire if it addresses nutrition and biochemical repair.

The post 2. Eating To Beat Disease appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 2. Eating To Beat Disease »

Powered by WPeMatico