2. Why Aging Minds Forget

Having an occasional memory lapse or fuzzy memory is normal, especially as you age. Most of the time, memory blips are due to typical age-related changes. Yet sometimes, memory complaints can herald cognitive changes to come.

In a study published in the journal Neurology, people in their 70s who complained of memory loss were more likely to develop mild cognitive impairment (MCI)—the stage that comes after normal age-related memory loss and sometimes precedes dementia—or dementia than those with no memory issues. However, the transition to MCI took about nine years, and the transition to full-blown dementia took 12 years, suggesting that even when dementia is imminent, its progression can be slow.

Treatable Conditions

The good news is that most memory problems are not related to dementia. In the majority of individuals, the problem stems from physical or emotional issues, or from the normal effects of aging.

Dehydration, fever, head injury, low thyroid function, liver and kidney problems, high blood pressure, obesity, poor nutrition, low blood sugar, and reactions to medications all are physical factors that can cause temporary memory impairment (see Chapter 3 for more on the causes of memory loss). Fortunately, these conditions can be treated.

Emotional distress also can have a devastating effect on memory. Repeated stress, sleeplessness, depression, and anxiety can interfere with the normal encoding and storage process, and can significantly affect your ability to remember even the simplest things.

Age-Associated Memory Impairment (AAMI)

In addition to the everyday memory loss caused by physical and emotional factors, aging itself can take a toll on memory. Age-Associated memory impairment (AAMI) is a natural process that starts early in life and progresses as we get older. We begin to lose brain cells (neurons) in our late 20s, a few at a time, although people who remain healthy and are mentally, socially, and physically active are able to generate new cells to replace many of these lost neurons. Our bodies also produce lower levels of the chemicals brain cells need to work. The combination of fewer brain cells and lower levels of brain chemicals changes the way the brain stores information and makes it harder to recall stored information.

The brain actually shrinks as we get older, losing both volume and weight. This shrinkage is the result of the gradual loss of neurons, and damage to the branch-like dendrites and nerve fibers called axons that extend from the neurons and connect them to other cells. Research suggests that changes in the brain’s “white matter”—the bundles of long, slender nerve fibers that project from neurons and enable them to communicate with other neurons—may be more to blame for age-associated memory decline than changes in the “gray matter”—areas in the brain’s cortex that are responsible for most important memory functions.

Other Age-Related Impacts

Other brain changes associated with age also are linked to memory decline. The surface brain tissue (gyri) shrink, and the grooves on the surface of the brain (sulci) widen. The volume of the ventricles (spaces in the brain that contain cerebrospinal fluid) increases. Blood flow to the brain decreases, as do levels of certain hormones and neurotransmitters that are involved in the transmission of signals among cells in the brain, and to and from the brain and other parts of the body.

Twisted protein filaments, called neurofibrillary tangles, may form inside nerve cells, and clusters of damaged beta-amyloid proteins, called plaques, may build up in the brain’s gray matter. These are the well-known markers of Alzheimer’s disease, but they are also present in the brains of older people who show no signs of dementia.

Cognitive Reserve

Not every brain falls prey to such damage, however. Some older people are able to retain exceptionally strong memories to age 80 and beyond. Brain scans performed on these still-sharp seniors have revealed that they have far fewer neurofibrillary tangles than most people, and they appear to be immune to the formation of the twisted filaments (although they can still develop plaques).

This resiliency to the ravages of age and conditions like Alzheimer’s disease is known as cognitive reserve. The concept first originated in the late 1980s, when researchers described 10 cases in which deceased individuals who had no apparent symptoms of dementia while they were alive showed signs of advanced Alzheimer’s disease in postmortem brain scans. Factors like education, an intellectually challenging career, exercise, and mentally and socially stimulating activities can all build up cognitive reserve. Research suggests people with more cognitive reserve are better able to stave off the degenerative brain changes associated with dementia.

When Changes Become Noticeable

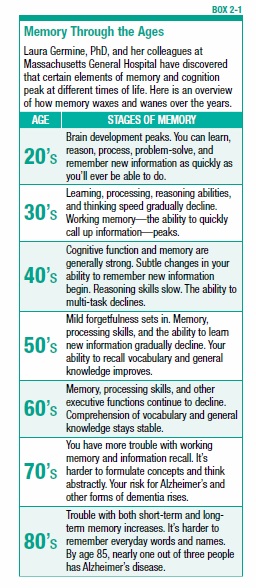

The effects of age-associated changes become most apparent after age 50, when people may begin to experience an increase in memory lapses. But subtle declines in cognitive skills such as reasoning, memory, and vocabulary skills may begin as early as in your 40s (see Box 2-1, “Memory Through the Ages”).

The older people are, the more difficulty they may have with short-term memory and mental organization. AAMI may cause people to misplace things more easily, occasionally forget a name or phone number, have more trouble multitasking, become easily distracted, or be unable to learn things as easily as they once did.

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI)

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is the stage that comes after age-associated memory impairment, and sometimes—but not always—leads to dementia (see Chapter 3). Currently, as many as 10 to 20 percent of Americans aged 65 and older have MCI, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. Although MCI is not the same as dementia, research suggests it may increase the risk of developing dementia or Alzheimer’s. According to Alzheimer’s Association statistics, as many as 15 percent of people with MCI may progress to dementia each year.

People with MCI have more trouble remembering things that once came easily to them—like appointments or phone numbers. They may also have difficulty performing a sequence of steps needed to finish a task—for example, following a recipe to cook beef stew. These memory problems are relatively mild, but patients with MCI perform worse on cognitive tests than others of the same age group.

People with MCI can still perform their daily activities, and have no apparent symptoms of dementia. They are able to follow written or spoken instructions, and can take care of themselves—for example, get dressed by themselves, prepare their meals without assistance, eat their meals, and go on walks without getting lost. In Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, these functions gradually disappear.

Having MCI doesn’t mean you can’t remember your children’s names and won’t be able to find your way from the supermarket to your house. Practice good lifestyle habits, like eating a nutritious diet, exercising, and managing health conditions that can impair brain function, such as high blood pressure, triglycerides, blood sugar, and LDL (bad) cholesterol levels, along with other risk factors, to reduce the likelihood that you’ll get MCI and that it will worsen. (To learn more about how diet, exercise, and lifestyle affect memory, see Chapter 8.)

If you believe you or a loved one may have MCI, consult a healthcare provider who can help determine whether the memory impairment may be associated with a treatable physical or mental disorder. Being seen by a doctor can help ensure that you or your loved one gets optimal care, and has access to new treatments for memory problems as soon as they become available. Meanwhile, reduce daily frustration by adopting strategies to help with forgetfulness, such as making lists and keeping calendars of appointments. With or without a diagnosis of MCI, one should still plan ahead and make decisions regarding future medical care and finances.

When Memory Impairment Becomes More Serious

Most people who live into their 70s, 80s, and beyond never experience memory problems more severe than normal age-associated slips. But for some, forgetfulness may get progressively worse, and begin to interfere with everyday functioning—important indications that there may be cause for concern. (See Chapter 3 for symptoms of serious memory problems.)

It’s important to consult a doctor if you or a loved one seems to be experiencing progressive memory loss. A medical assessment may reveal that the problem is associated with a treatable physical disorder, rather than an irreversible condition such as Alzheimer’s disease.

The post 2. Why Aging Minds Forget appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 2. Why Aging Minds Forget »

Powered by WPeMatico