3. Dementia

MCI to Dementia

Progressing from MCI to dementia means the difference between forgetting names, dates, or what you intended to buy at the supermarket, and having significant trouble functioning in your day-to-day life. The progression of MCI to dementia can alter many aspects of who you are, including your memory, personality and behavior.

Dementia comes in two forms:

- Primary dementias—such as Alzheimer’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)—involve damage to or wasting away of the brain tissue.

- Secondary dementias are memory troubles caused by mental or physical disorders, such as depression or thyroid problems.

Signs of dementia may include:

- Asking the same questions over and over

- Losing the ability to accomplish complex tasks, such as cooking a meal

- Becoming lost in once-familiar places

- Forgetting names of familiar people

- Having trouble using language, or putting words together

- Failing to remember regular appointments

- Neglecting personal hygiene—such as brushing your teeth or showering

- Showing signs of mental confusion

- Having a hard time recognizing common objects, like a toothbrush or TV set

- Having trouble coordinating movements

- Experiencing mood symptoms such as anxiety, unusual irritability, or depression.

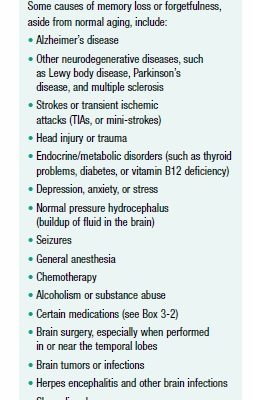

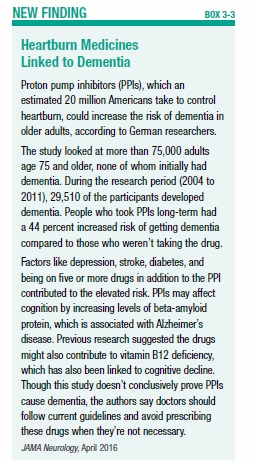

Causes of Reversible Dementia

Dementia, as well as simple memory loss, can be triggered by medical or psychiatric conditions, such as a high fever, vitamin deficiency, head trauma, or depression (see Box 3-1, “Causes of Memory Loss”). This type of dementia is known as secondary dementia. Because many causes of secondary dementia are reversible with treatment, it’s important to see a doctor if you’re experiencing progressive memory-loss symptoms, especially if your health has recently changed.

The following are among the more common reversible causes of memory loss:

Tobacco and Alcohol

In addition to increasing your risk for many diseases—including cancer—smoking can take a toll on your cognitive ability. Smoking affects memory in several ways. It damages the heart and blood vessels, limiting crucial blood flow to the brain and increasing the risk for stroke. It increases levels of homocysteine—a damaging amino acid that contributes to stroke and dementia risk. And it injures the lungs, reducing the supply of nourishing oxygen to the brain. Studies have noted a link between cigarette smoking and learning deficiencies, memory processing speeds, and working memory. Smokers face a 45 percent greater risk for dementia than nonsmokers. Fortunately, research is also finding that quitting smoking can help preserve memory.

Moderate drinking (one or two glasses a day) shouldn’t affect your cognitive function. It may even provide some mild benefits. A recent report in the American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias found that moderate alcohol use might improve episodic memory and enlarge the hippocampus in adults over age 60. While the study suggests that one drink per day is associated with a larger hippocampal volume than abstaining from alcohol, researchers do not advise drinking solely in hopes of boosting brain function.

The key really is moderation, because too much alcohol can have significant negative impacts on your brain and overall health. Beer, wine, and liquor contain ethyl alcohol, a central nervous system depressant that impairs thought processes, motor control and memory, and slows overall brain activity. Going on a drinking binge can leave you with transient amnesia (sometimes referred to as a “blackout”). Chronic alcohol abuse can lead to sometimes-irreversible dementia due to the combined toxic effects of alcohol and the nutritional deficiencies associated with alcoholism, particularly a lack of thiamine (vitamin B1).

Heavy drinking (more than two alcoholic drinks per day), even without alcohol dependency, can be harmful, research shows—especially when combined with heavy smoking (a pack or more of cigarettes a day). If you have a family history of alcohol abuse, you should be especially vigilant and aware of the potentially damaging effects of alcohol on brain function.

Inflammation of the Brain

Infections that cause brain inflammation, particularly meningitis and encephalitis, can contribute to mental decline if they’re not treated quickly and effectively. Meningitis affects the meninges, the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. Encephalitis affects the brain tissue itself. After one of these illnesses, you can continue to have memory loss for months. Getting prompt treatment can reduce the chance of permanent cognitive loss. Treatment for both conditions may include antibiotics (often administered intravenously in the hospital) and antiviral drugs (if the disease was caused by a virus).

Even general inflammation throughout the body can contribute to memory loss. Too much C-reactive protein (CRP), an indicator of inflammation) in the blood has been linked with impairment of executive thinking (the type of thinking involved in planning and abstract reasoning).

Depression and Anxiety

Major depression has implications that go far beyond a shift in mood. Long-term chronic depression has a marked effect on the brain: It alters levels of key brain chemicals such as serotonin and norepinephrine, slows activity in the parts of the brain associated with executive function and perception, and shrinks the hippocampus (the part of the brain where memory is processed). Untreated depression is associated with a higher risk for dementia. In particular, depression symptoms that steadily get worse have been linked to a higher risk of dementia. This finding suggests depression is also an early warning sign of cognitive impairment.

Signs that you may be depressed include feelings of sadness and hopelessness that last for two weeks or longer. You’ll likely also notice changes in sleep and appetite, restlessness, fatigue, irritability, and a loss of interest in activities you once enjoyed. You can even develop symptoms that mimic dementia, such as confusion, impaired memory, and trouble focusing.

Drug Effects and Interactions

Sometimes the cause of memory loss may be lurking behind the door of your medicine cabinet. Certain classes of prescription and over-the-counter drugs, including antidepressants, sleeping pills, anti-anxiety drugs, anticholinergic drugs, opioid pain medications, and some antihistamines, are known to affect memory and brain function (see Box 3-2, Drugs Linked to Memory Impairment).

“Older individuals are more vulnerable to memory impairment related to medical treatment,” explains Anthony P. Weiner, MD, director of MGH Outpatient Geriatric Psychiatry. Age-associated changes in the brain can make you more sensitive to medications. Changes in metabolism and reduced liver and kidney function slow the rate at which your body clears drugs. As a result, you may take another dose of medicine when the first one hasn’t yet left your system, compounding the side effects.

One class of drugs that has been repeatedly linked to dementia is the benzodiazepines, which are widely used by older adults to treat anxiety and insomnia. Yet the findings on benzodiazepines have swung back and forth over the years. A French/Canadian study in BMJ found that people in their late 60s and older who took a benzodiazepine drug such as diazepam (Valium) or flurazepam (Dalmane) were more likely to develop dementia, especially if they stayed on the drug for more than six months. Yet a 2016 study in the same journal did not find any increased risk of dementia with benzodiazepine use. While the case on benzodiazepines and cognitive health is far from closed, experts say other side effects associated with these drugs, including falls, confusion, and sedation, should be enough to give doctors pause before prescribing them to seniors.

Cancer drugs also contribute to cognitive issues. Patients who receive chemotherapy or radiation often develop memory loss, confusion, and difficulty concentrating, a phenomenon that has been termed “chemo brain.” Memory problems can last for six months or more after treatment ends.

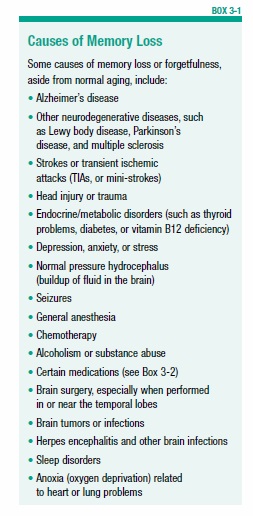

New research suggests a class of drugs used to treat heartburn might play a role in memory loss (see Box 3-3, “Heartburn Medicines Linked to Dementia”).

If you recently began taking a new drug or switched to a higher dose of an existing medication, and you are experiencing memory problems, ask your doctor whether your medicines might be affecting your memory. You can usually resolve drug-related memory impairment by switching medications, changing the dose, or stopping the drug entirely.

Lung Problems

Keeping your lungs healthy and functioning at optimal capacity is important for your brain, studies suggest. When the lungs don’t work well, the brain is deprived of the nourishing oxygen it needs to function optimally. Treating conditions that impair respiratory function—such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), fibrosis, and asthma—can help improve memory performance. In some cases, treatment may also lower long-term risk of more serious memory impairment.

Even seasonal allergies can impair cognitive functions such as attention and memory, in part by causing repeated awakenings that lower sleep quality. Sleep disturbances increase risk for depression and cognitive problems. Older adults may be even more vulnerable than younger people to brain effects from allergies because they’re more likely to have co-existing medical conditions, such as sleep apnea and heart conditions.

Metabolic Disease or Abnormalities

Certain metabolic diseases, such as thyroid disease, diabetes, and liver or kidney failure, can wreak havoc on your memory, researchers have found.

Thyroid Function

The butterfly-shaped thyroid gland in the neck produces hormones that regulate the body’s metabolism. High or low levels of thyroid hormones can lead to cognitive impairment, especially in older people. In middle age and beyond, an underactive (hypo) or overactive (hyper) thyroid gland has been linked with impairments of memory, visuospatial organization, attention, and reaction time. Even subtle variations in thyroid function can cause significant’scognitive effects.

Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus—a disease in which the body cannot use glucose (sugar) properly—can also cause cognitive symptoms that may be mistaken for dementia. In type 1 diabetes, an autoimmune condition, the pancreas can’t produce enough of the hormone insulin to move sugar from the bloodstream into the cells. In type 2 diabetes, the body becomes less sensitive to the effects of insulin. Both conditions result in higher-than-normal blood sugar levels.

Diabetes may hasten cognitive decline by contributing to hardening and narrowing of blood vessels (atherosclerosis), which can reduce or block blood flow to brain tissue and deprive brain cells of necessary oxygen and nutrients. Depending on where the blockage in the blood vessel occurs, memory can be affected. Some studies suggest that diabetes may be associated with atrophy in the brain’s frontal lobes (responsible for attention and long-term memory) and temporal lobes (responsible for language skills and memory of verbal and non-verbal information). Other research suggests that beta-amyloid, a protein that builds up in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease, also forms in the pancreas of people with type 2 diabetes, raising the possibility that the same underlying factors may lead to both conditions.

Diabetes coupled with depression may further increase the odds of developing dementia, according to an recent study in JAMA Psychiatry. The researchers say that identifying and managing both conditions is critical to lowering dementia risk. Older adults should be routinely checked for elevated blood glucose levels— the hallmark of diabetes—and those with diabetes should be watched carefully for signs of depression.

In people who already have symptoms of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), diabetes is especially troublesome. Researchers have found that individuals with both conditions are at much greater risk of progressing to dementia than individuals who have MCI but not diabetes.

Keeping diabetes under control can help prevent many complications of the disease, including memory problems. Managing diabetes involves eating healthy, exercising, carefully monitoring blood sugar levels, and taking diabetes medications, if necessary. Losing weight, and especially belly fat, also may help avoid harm to your memory.

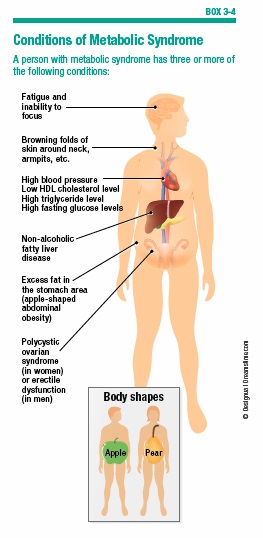

Metabolic Syndrome

People with metabolic syndrome have a cluster of risk factors, such as abdominal obesity, low levels of HDL cholesterol, high triglyceride levels, and high blood pressure (see Box 3-4, “Conditions of Metabolic Syndrome”). They also have insulin resistance, in which the body can’t respond appropriately to insulin produced by the pancreas. As a result, glucose doesn’t leave the blood and enter the cells as it should. The pancreas produces more insulin to compensate, and this excess insulin can lead to inflammation and damage to the brain.

Excess belly fat associated with metabolic syndrome (having an apple shape as opposed to a pear shape) has also been linked to increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers think toxins and hormones secreted by abdominal fat may damage the brain.

Sleep Problems

Most people need at least seven to nine hours of sleep each night for their memory to perform at its peak. With age, it’s common to have greater difficulty falling or staying asleep, often because of underlying problems such as arthritis, pain, depression, or frequent urination.

Research shows a direct link between sleep deprivation and memory loss. A University of California, San Francisco study found that veterans with sleep problems, such as apnea or insomnia, faced a 30 percent increased risk of developing dementia. The inability to sleep through the night without interruption is also proving to be a risk factor for Alzheimer’s. Older adults who wake up frequently (more than five times a night) are significantly more likely than sound sleepers to have amyloid markers in their spinal fluid and amyloid plaque buildup in their brains—both indicators of Alzheimer’s disease.

Although researchers don’t know for sure whether sleep disturbance is a risk factor for dementia or an early symptom of the condition, it is clear that optimizing sleep time will not only make you feel more rested, but also less forgetful and better able to cope with stress. Getting a good night’s sleep also might help improve your ability to retain new information. See Chapter 8 for strategies to improve the quality—and quantity of sleep.

Sleep Apnea and Other Disorders

Conditions that disrupt sleep, such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and restless legs syndrome (RLS), may be linked to memory problems. In OSA—a condition sometimes associated with obesity—muscles in the upper airway that support the soft palate, tongue, and other structures relax and collapse, blocking the air passages. The brain must continually jolt the body awake to restart breathing. People with sleep apnea may be unaware they are waking up, but they feel tired the next day. A bed partner may hear them snore or repeatedly stop breathing. Untreated sleep apnea can increase the risk for stroke. This risk may be due, in part, to wear and tear on the brain caused by fluctuations in blood pressure.

It’s important to watch out for snoring—the most obvious outward sign of sleep apnea—because it can also warn of memory loss at an early age. People with OSA are diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment nearly 10 years earlier than those who don’t experience pauses in breathing. They also develop Alzheimer’s five years earlier than those without apnea. The positive news is that damage to the brain from sleep apnea may be reversed, and early cognitive impairment prevented, with a treatment called continuous positive airway pressure therapy (CPAP). CPAP uses a machine that pumps air through the nose and/or mouth to prevent the airway from collapsing. This treatment may also help prevent the buildup of beta-amyloid proteins in the brain.

RLS interferes with sleep by causing unpleasant sensations in the legs that occur just before falling asleep or during the night. Today, medications are available to help with RLS, including pramipexole (Mirapex), rotigotine (Neupro), and ropinirole (Requip).

Stress

Major life stressors, such as going through a financial crisis, experiencing a catastrophic accident, working in a demanding job, or losing a loved one, can contribute to memory loss. When your body is under duress, it releases excessive amounts of stress hormones, which can damage brain cells involved in memory. People with certain gene variations may be especially vulnerable to the effects of stress.

Learning how to manage your stress and anxiety is important for keeping your memory functioning at its peak. See Chapter 8 for ways to manage daily stress in your life.

Vitamin Deficiency

As you age, your rate of nutrient absorption slows, making it harder for your system to get the essential vitamins it needs. If you drink alcohol or smoke, your risk for vitamin deficiencies increases, because both behaviors leach nutrients from the body.

B Vitamins

The B vitamins—especially B12, B6, and folate—promote healthy nerves and red blood cells. They’re found naturally in animal-sourced foods (meat, fish, poultry, eggs, and dairy products) and in fortified cereals, beans, and dark green vegetables. People with a B vitamin deficiency often have elevated levels of the amino acid homocysteine, which is damaging to brain cells and blood vessels. This damage may have serious consequences for cognition, especially in older people.

A deficiency of vitamin B1 (thiamine) is common in people who abuse alcohol, and who don’t properly absorb nutrients from foods as a result. B1 deficiency leads to two brain disorders—Wernicke encephalopathy and Korsakoff syndrome (known collectively as Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome). Without vitamin B1, the brain can’t produce enough energy to function properly, which leads to damage in brain areas responsible for memory. People with these conditions can be permanently unable to create new memories.

Vitamin B12 is essential for proper brain functioning. The inability to absorb this vitamin in the GI tract—a condition called pernicious anemia—can damage brain cells and lead to cognitive changes that mimic the symptoms of dementia. An estimated one to two percent of older adults have pernicious anemia. Without treatment, a vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to increasing memory loss and progressive nerve damage. Early treatment with regular B12 injections can help recover some, if not all, lost memory function. For older adults without pernicious anemia, B12 supplementation may not do much, if anything to help preserve mental function, however.

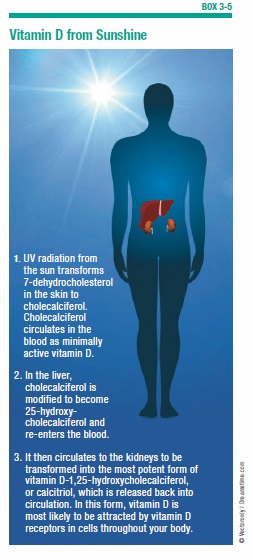

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is not really a vitamin—it’s a hormone produced by the action of ultraviolet light (UVB) on the skin (see Box 3-5, “Vitamin D from Sunshine,” on page 29). This vitamin has wide-ranging effects in the nervous system, nurturing brain and nerve development and protecting them against injury. When vitamin D is lacking, brain function may suffer—a real concern, considering that 70 to 80 percent of people older than 75 are thought to be deficient.

Some studies have found that older adults with low blood levels of vitamin D perform worse on cognitive tests than those with normal blood levels of the vitamin. A study in Neurology linked vitamin D deficiency with greater dementia and Alzheimer’s risk. The greater the deficiency, the more the dementia risk rose. However, the study could not confirm that vitamin D status, and not other factors, was responsible for the increased dementia risk.

If there is a link, taking vitamin D supplements might help preserve cognitive function. Or, the solution might be as simple as spending more time outdoors. To boost your vitamin D levels from sunlight, you may need only five to 30 minutes of unprotected sun exposure a couple of days a week. People who live in cloudy or cold climates might still need to rely almost solely on supplements to get their daily vitamin D allowance.

Causes of Irreversible Dementia

Some types of dementia are caused by progressive brain damage, and are irreversible. These are known as primary dementias. The most commonly known form of irreversible dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, which is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4. The following are other causes of progressive dementia:

Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB)

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is the third most common form of dementia, after Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Between 10 and 25 percent of dementia cases are of this form. In people with DLB, abnormal proteins called Lewy bodies build up inside neurons in the part of the brain responsible for memory, language, and consciousness. These same proteins can also be found in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

In fact, people with DLB often develop Parkinson’s-like symptoms, including rigid muscles and a shuffling walk. Other symptoms include confusion, trouble thinking and reasoning, hallucinations, and delusions. Although no cure exists for DLB, cholinesterase inhibitor drugs such as donepezil (Aricept) and rivastigmine (Exelon) can help control the cognitive symptoms.

Fronto-Temporal Dementias (FTD)

This spectrum of disorders causes parts of the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain, which control memory, personality, and language skills, to slowly atrophy. FTD isn’t as common as Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia, but it may account for up to 15 percent of all dementias. In younger people it’s even more common, accounting for up to 50 percent of dementias in those younger than 65.

Symptoms of FTD tend to come on slowly, and typically involve inappropriate behavior, difficulty finding the right words, and personality changes. In its late stages, FTD resembles Alzheimer’s disease, with significant memory impairment. Although no treatment for FTD exists, antidepressants and antipsychotic drugs may help control the behavioral symptoms.

Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

We tend to associate Parkinson’s disease (PD) with movement problems, but it can affect cognition as well. PD occurs when brain cells that produce the chemical dopamine die. Because dopamine is essential for normal movement, people with PD develop muscle rigidity in the limbs, as well as tremors and balance difficulties.

People with PD also have abnormal deposits of Lewy bodies (the same protein found in people with dementia), as well as the hallmark plaques and tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. An estimated 50 to 80 percent of people with Parkinson’s disease will eventually develop dementia. As with other forms of dementia, Parkinson’s-related cognitive issues get worse over time.

The cholinesterase inhibitor rivastigmine (Exelon) is FDA-approved to treat cognitive problems due to Parkinson’s. It’s important to note that many of the drugs used to treat Parkinson’s, including anticholinergic drugs and L-dopa, can potentially cause or worsen cognitive, mood, and thought disorders (e.g., hallucinations and delusions). Working closely with a doctor can help people with Parkinson’s disease find the drug with the highest benefit in proportion to risk. Another medication, memantine (Namenda), which is already approved for use in moderate-to-severe AD, may also be effective against Parkinson’s disease. Nilotinib is a new drug (used in the treatment of leukemia) recently being tested, in phase 1 trials, for treatment of PD and DLB—the preliminary reports note hope for a potential treatment. The drug was well tolerated and patients noted improvements in motor skills and cognitve function.

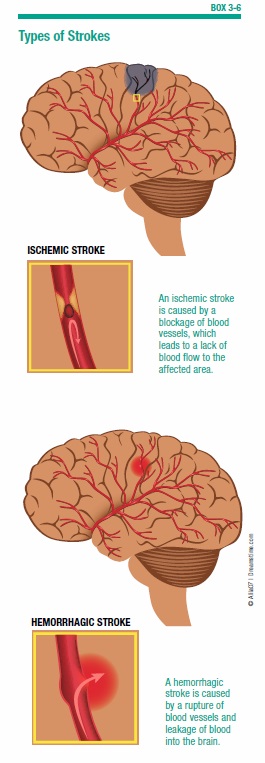

Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Disease

The health of the heart and brain are closely connected. Many conditions that damage the heart increase the risk for strokes and other cognitive damage (see Box 3-6, “Types of Strokes”).

Research continues to show how poor heart health is strongly linked to a greater risk of memory decline. People with poor heart function are two to three times more likely to develop memory loss, according to a 2015 study published in Circulation. “Heart function could prove to be a major risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease,” said lead author Angela Jefferson, PhD, director of the Vanderbilt Memory and Alzheimer’s Center. But there’s good news out of the study, too. “A very encouraging aspect of our findings is that heart health is a modifiable risk. You may not be able to change your genetics or family history, but you can engage in a heart healthy lifestyle through diet and exercise at any point in your lifetime.”

Atrial Fibrillation and Memory Problems

Atrial fibrillation (Afib), an abnormal heart rhythm in which chaotic pumping actions cause blood to pool, increases risk for AD and other forms of dementia by increasing the formation of blood clots that can lead to stroke. One in 20 people over age 65, and one in 10 over 80, has Afib.

Research suggests Afib also dramatically increases the risk for dementia in people who haven’t had a stroke. Afib may be associated with mild cerebrovascular disease that, if left untreated over time, could lead to gradual cognitive decline. This finding underscores the importance of managing cardiovascular risk factors to maintain brain health.

Treatment for Afib usually begins with medication, such as drugs to slow the heart rate and blood thinners to reduce the risk of blood clots. If that doesn’t work, the next step might include cardioversion, which uses electricity delivered through paddles on the chest, or drugs to restore an erratically beating heart to its normal rhythm. A treatment called catheter ablation, which burns off heart cells that are producing the abnormal rhythm, may also reduce stroke risk.

Strokes and Transient Ischemic Attacks

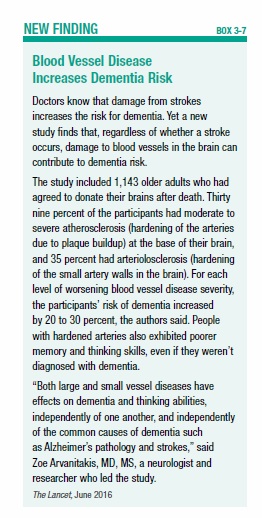

In about a quarter of cases, severe memory loss is triggered by strokes that destroy cells in regions of the brain involved in learning and memory. During a stroke, blood vessels in the brain are blocked or rupture, starving brain cells of oxygen and nutrients. But even without a stroke occurring, damaged blood vessels in the brain may contribute to dementia risk, finds a study in The Lancet Neurology (see Box 3-7, “Blood Vessel Disease Increases Dementia Risk”).

Sometimes, the damage from a stroke occurs slowly, over time, as a series of tiny strokes progressively destroy small sections of brain cells. These transient ischemic attacks (TIAs, or “mini-strokes”) gradually reduce the nutrient-rich blood supply to brain cells. Whether damage occurs from one large stroke or a series of small ones, the death of blood vessels in the brain can lead to a condition called vascular dementia (VaD). VaD is the second most common cause of dementia after Alzheimer’s.

When a stroke occurs, every second counts. Getting treated with a clot-busting drug can minimize brain damage, but only when it’s given within three to four hours of when the stroke began. Knowing the signs of stroke, such as difficulty speaking or temporary weakness or numbness of an arm or leg, can help you get treatment when it can help most (see Chapter 4).

Although TIAs and minor strokes usually do not cause permanent damage, they require prompt attention to reduce the risk of another, more serious stroke. With multiple small strokes, symptoms usually appear gradually as the damage spreads, and can include memory loss, shuffling movements, inappropriate behavior, and loss of bladder or bowel control.

Although you can’t reverse the damage caused by a stroke, TIA, or other forms of VaD, you may be able to avoid further injury to brain cells by lowering cardiovascular risk factors through simple lifestyle changes. Controlling blood pressure and cholesterol, losing weight, quitting smoking, and managing conditions such as diabetes, atrial fibrillation, and coronary artery disease can reduce the risk of vascular events. Eating well and exercising regularly also can help. Researchers are looking at whether cholinesterase inhibitor drugs used to treat dementia, such as memantine, donepezil (Aricept), galantamine (Razadyne) and rivastigmine (Exelon), might be effective for VaD.

Chronic Inflammation

Chronic inflammation, caused by an immune system gone haywire, has also been implicated in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. A team of researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital has found evidence that chronic activation of the immune system in response to an infection of the central nervous system—or to known AD risk factors such as stroke or head injury—might trigger excessive production and accumulation of beta-amyloid in the brain. Beta-amyloid proteins are toxic to brain cells, and are a primary constituent of brain plaques associated with Alzheimer’s. Determining what factors trigger the immune system and cause the accumulation of beta-amyloid may lead to promising new therapies to prevent or control the inflammatory response.

MGH research is also focusing on a molecular “switch” that may regulate inflammatory processes involved in diseases such as Alzheimer’s. In animal models, researchers found that the molecule nitric oxide acts on a protein called SIRT1 to trigger inflammation and cell death. The same sequence of events may play a role in conditions like diabetes and atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries). The next step is to find substances that will suppress this pro-inflammatory switch.

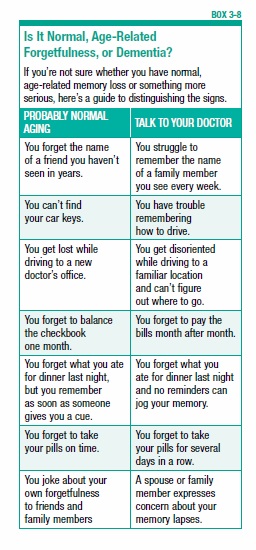

The Warning Signs

Everyone has the occasional mental slip—forgetting a name or the title of a movie you saw a few years ago. More concerning signs are forgetting how to do things that are routine for you—like finding your way down a well-traveled route, or cooking a meal you’ve been making for years. Other signs that you may have a serious memory problem are asking people to repeat themselves many times, having significantly more trouble learning new skills than you used to, or having difficulty with simple transactions (for example, writing a check).

“It’s not just occasional forgetting, it’s in memory and other areas of cognitive function that impair your ability to do many everyday activities,” says William Falk, MD, director of Geriatric Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital. “You may have difficulty remembering what to call many things, or forget the names of people close to you. You may fail to recognize familiar objects or people. You may find complex tasks impossible to accomplish. Things you used to do before you can’t do now. Often, other people may notice your memory problems before you do. At this point, other contributing factors must be ruled out. You must be evaluated by a doctor.” (See Box 3-8, “Is It Normal Age-Related Forgetfulness, or Dementia?”).

Anyone who has dementia should be under the care of a family doctor, internist, neurologist, psychiatrist, or geriatrician. A doctor should be able to determine whether your memory problems are caused by a treatable condition, such as the side effects of medicine, thyroid problems, or a bout of depression. Even if the doctor diagnoses an irreversible form of dementia, it is possible to treat the physical and behavioral problems associated with the condition, and to get help coping with it.

The post 3. Dementia appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 3. Dementia »

Powered by WPeMatico