8. Caring for a person with Alzheimer’s Disease

If a loved one has Alzheimer’s disease and you will be the primary caregiver, there’s much you need to know, both about how to care for the person with the condition and about how to care for yourself. More than half of the people with Alzheimer’s disease are cared for at home. This chapter will review some general information about caring for a person with Alzheimer’s disease. The next chapter is about services for the caregiver.

First and foremost, you should know that there are many resources available to help you, and you should avail yourself of as many of them as you need. Several helpful agencies are listed in Appendix II: Resources, on page 96. One in particular is the Alzheimer’s Association: a nonprofit organization dedicated to providing education and support for people diagnosed with the condition, as well as for their families and caregivers.

The Alzheimer’s Association has a network of support groups throughout the United States. They can be extremely helpful in a number of ways. For one thing, you will feel less alone. You are not the only person coping with a difficult transition in your life. Over 15 million Americans are currently providing unpaid care for a person with Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

Once a person is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, he or she will require increasing amounts of assistance with daily life. This help can come from a spouse, child, other close family member, friend, or paid caregiver. One person can manage this task in the mild stage of the condition. As the disease progresses, however, additional help, and more outside services, will be needed. This chapter will review some care options, such as adult day services, respite care, in-home care, and nursing home care, and will offer suggestions to help you care for a person with Alzheimer’s disease.

Care Options

Most people with Alzheimer’s disease live at home, with care provided by family and friends. But there are other care options. The living situation for each individual will depend to a large extent on the current family situation.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, about 800,000 people with Alzheimer’s disease (more than one in seven) live alone. A person with Alzheimer’s disease who lives alone with no family close by may be able to manage for a while in the mild stage of the disease. But the person will need to be taken in by a family member, have in-home care, or move to an assisted living facility or nursing home before the disease makes living alone dangerous. People with Alzheimer’s disease can put themselves in danger in several ways, such as forgetting to turn off the stove, opening the door to a stranger who may rob them, forgetting to eat, or scalding themselves with hot water.

If the person with Alzheimer’s disease is living with a spouse, child, or another adult who has good mental function, and is in reasonably good health, it’s possible to remain in the home. At some point, a home health aide may be needed (part-time or full-time) to help with care. If the person with Alzheimer’s disease is being cared for at home, respite care services may be helpful for providing relief for the caregiver and to give the patient a social outlet.

Adult Day Services

Adult day services, which serve adults who are physically or cognitively impaired, are one type of respite care. This is a place where people with Alzheimer’s disease can come for part of the day to interact socially and engage in recreational activities in a safe and supportive environment.

Adult day services offer caregivers a chance to go to their job or have free time without worrying about the safety of their loved one. Adult day programs offer people with Alzheimer’s disease a place where they can interact with other people, receive services such as physical or speech therapy, and get some exercise.

Most adult day services will pick up and drop off participants and provide nursing care, personal care, counseling, therapeutic activities, and rehabilitation therapies. These may include reminiscence groups, exercise classes, arts and crafts, and music therapy. A meal is usually provided, as well as assistance with daily activities.

The number of adult day services has been growing over recent years to meet the increasing demand. To find one in your area, look in the Yellow Pages (under adult day care, adult day services, or senior citizen services), online resources include the National Association of Area Agencies on Aging (www.n4a.org) where you can search for agencies in your local area. A local senior center and your doctor can also suggest some resources.

Adult day programs are offered by hospitals, nursing homes, senior centers, and religious, fraternal, and neighborhood organizations. Depending on the type of organization providing the service, the cost can vary widely. Some programs may use a sliding scale or even be free. Adult day services are not covered by Medicare, but they may be covered by Medicaid or private long-term care insurance.

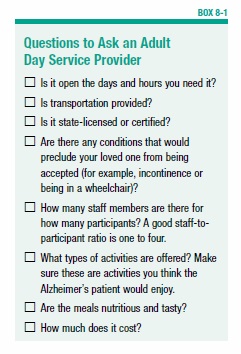

Once you’ve identified one or more adult day services, you should do some investigating (some questions to ask are listed in Box 8-1, “Questions to Ask an Adult Day Service Provider”). It’s also a good idea to pay a visit and see for yourself whether it meets the needs of your loved one. Look for a clean and pleasant atmosphere with sturdy, comfortable furniture. Watch the staff interact with participants. You may want to try out the service for three or four days before making a longer-term commitment.

Because an adult day service is an unfamiliar setting, it will probably take several visits before a person with Alzheimer’s disease feels comfortable there. The caregiver may want to accompany him the first few times until he adjusts.

Longer-Term Respite Care

There can be times when you are unable to carry out caregiving tasks for several days. For example, an emergency may arise or you may go on vacation. For these times, many nursing homes or assisted-living facilities offer respite care programs, usually for up to three weeks. You can find a respite care program in your area by contacting your local chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association or the Area Agency on Aging.

In-Home Care

Home care services can fulfill duties ranging from helping with housework to providing skilled nursing care. In the mild stage of the disease, a homemaker or chore worker may be hired to do housekeeping, meal preparation, and shopping. The caregiver also can accompany the person to appointments, the movies, or other activities. These workers don’t provide hands-on care, but they do make it possible for people with Alzheimer’s disease to continue functioning independently for a longer period of time.

Home health aides are the next level of care. They assist patients with daily activities, such as bathing, dressing, eating, and using the toilet. Home health aides are not nurses, but they are usually required to receive training and to work under the supervision of a nurse. Depending on the individual needs of a person with Alzheimer’s, home health aides may be necessary from a few hours a day to 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

In-home caregivers can be hired privately or through a home health agency. You can get a referral from your physician or social worker, check the Yellow Pages, or contact the Area Agency on Aging. Also, the National Association for Home Care & Hospice has a Home Care Locator on their website (www.nahc.org), which lists home care agencies across the U.S. The national median daily rate for home health aides is $127, according to the Genworth Cost of Care Survey. For homemaker or companion services, the median daily rate is $125. These costs will vary depending on where you live.

Some states require home care agencies to be licensed and to meet minimum standards. If your state has these requirements, check to see if the home care agency you’re considering is licensed.

In most cases, the cost of home care is borne by the patient and family. Medicare, Medicaid, and most health insurance plans have strict guidelines for covering home healthcare, and many Alzheimer’s patients do not qualify. Long-term care insurance will cover home care if the patient and caregivers meet certain criteria.

Housing Options

At some point between the mild and severe stage of the disease, it may make sense for the person with Alzheimer’s to move to an assisted-living facility or nursing home. The decision to move someone to one of these facilities is rarely easy. The timing will depend on individual circumstances. A person living alone will need to move to the safety of an assisted-living facility or nursing home sooner than someone who has a caregiver at home. For the caregiver, the decision is more complex.

Caregiving can be very stressful. Some people move a loved one when caregiving becomes overly burdensome. This may be when the person with Alzheimer’s becomes incontinent or behaviors become unmanageable.

One study found that counseling can help caregivers better cope with memory and behavior problems, which relieves some of the stress of caregiving. Receiving this type of counseling often delays the need to place the person in a nursing home. This is significant, in part because of the high cost of nursing home care. Rates for assisted-living facilities are less, but the cost is still high.

Nevertheless, it might eventually become necessary to move the person with Alzheimer’s disease to an assisted-living facility or nursing home. Which facility is most appropriate will depend on the person’s health. A person with few medical problems aside from Alzheimer’s disease can live in an assisted-living facility that is set up to accommodate residents with dementia. If the person has other medical problems, placement in a nursing home may be the better option.

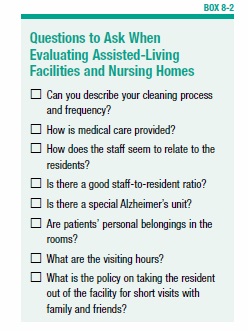

Selecting an assisted-living facility or nursing home can be difficult. Just as with choosing an adult day service, you need to thoroughly check out the facilities you are considering. Get recommendations from your physician, social worker, clergy, family, or friends. Visit each facility and ask questions (see Box 8-2, “Questions to Ask When Evaluating Assisted-Living Facilities and Nursing Homes”). The Medicare website has detailed information about the past performance of every Medicare and Medicaid certified nursing home in the country (http://1.usa.gov/YAtMPK).

Assisted-Living Facilities

Assisted-living facilities were first conceived to provide healthy older adults with an essentially independent, but communal living environment. They rent a room or apartment and provide meals, along with housekeeping and laundry services, but they do not offer nursing services. Depending on the facility, assistance with daily activities, such as bathing and dressing, may be available. An assisted-living facility may be acceptable for a healthy person in the mild stage of Alzheimer’s disease.

Some assisted-living facilities also have sections specifically designed for people with Alzheimer’s disease. They offer a safe environment, special assistance for people with the disease, and appropriate activities. An assisted-living facility with a designated Alzheimer’s unit can usually accept people at any stage of the disease if they are otherwise reasonably healthy.

A word of caution: Assisted-living facilities are not as closely monitored as nursing homes. They are not necessarily state-licensed, and regulations vary from state to state. The quality of the facilities and of the care varies widely. Take the time to thoroughly investigate a facility before choosing it, and make sure it’s licensed. Also, make sure the facility is in compliance with all state regulations. Contact your state office on the aging to find out what laws and regulations apply.

In addition to taking an official tour of the facility, show up unannounced and observe the conditions on your own. When choosing an assisted-living facility, you’ll be given a contract to sign. Show the contract to a lawyer who has expertise in elder law before signing.

The national median monthly cost for a private, one-bedroom unit in an assisted living residence is $3,628 per month, according to the Genworth Cost of Care Survey. Costs vary by state. The pricing can be complex and dependent on the services the resident needs. Assisted-living residences that provide specialized dementia care often charge additional monthly fees.

Long-term health insurance does not cover assisted living, and you can’t count on Medicaid to pay the bill. Although in certain states, Medicaid will pay for some services provided in an assisted-living facility, the overall cost is borne by the individual.

Nursing Homes

Skilled nursing facilities (nursing homes) offer the highest level of care and may be appropriate for people in the moderate or severe stages of Alzheimer’s disease. They provide 24-hour nursing care and supervision, including help with bathing and grooming, medical and nursing care, and activities.

Many nursing homes have added separate special-care units to meet the needs of people with dementia. The living spaces in these units will have features such as secured exits, single-occupancy rooms, small dining rooms, and designated indoor and outdoor areas for wandering. Activities accommodate the cognitive deficits of people with Alzheimer’s.

The national median cost of a private room in a nursing home is $7,698 month and $6,844 a month for a semi-private room, according to the Genworth Cost of Care Survey. Costs vary by state. For those who are eligible, Medicaid will help pay the cost, but it can be difficult to qualify for Medicaid if you have financial assets. Speak to an eldercare lawyer to learn about your rights and benefits.

Once you’ve made a choice and moved your loved one into an assisted-living facility or nursing home, you need to maintain an active presence. Even though nursing homes are required to meet certain standards, it’s a good idea to continue to oversee the patient’s care.

Geriatric Care Managers

Understanding the various care options and making decisions about what is best for a loved one can overwhelm family members of a person with Alzheimer’s disease. Professional assistance is available. Geriatric care managers are professionals (usually social workers) who can be hired to assist in a number of ways. Care managers—who usually charge $50 to $200 per hour—can perform an assessment of a person in their home, and devise strategies to keep them safe and help compensate for some of the memory problems. They can also assist with hiring caregivers, and can act as liaison to family members living far away.

A geriatric care manager can also help to determine if assisted living or nursing care is necessary. They can provide a one-time assessment and recommendations, or they can oversee care over the long term. To find a geriatric care manager in your area, contact the Aging Life Care Association (www.aginglifecare.org).

If you can’t afford a geriatric care manager, contact your local office on aging for help. They may be able to send a case manager to do an assessment at no charge. To find the agency near you, enter your zip code at the website www.eldercare.gov.

The Challenges of Caregiving

As a person with Alzheimer’s disease loses the ability to function in certain ways, he or she will increasingly require help. In general, the caregiver must be the patient’s advocate, ensuring his or her safety, medical wellbeing, and financial security. The caregiver must assist with day-to-day activities and provide emotional support. Caregivers must compensate for the patient’s cognitive problems and cope with the behavioral problems.

In the mild stage, people with Alzheimer’s disease can usually manage on their own, provided that someone checks on them regularly (at least once a day). However, they will most likely need help with finances, and they may need someone to do the grocery shopping. As the disease progresses, they will need increasing assistance with household activities.

In the moderate stage, living alone is no longer an option. Assistance will be required with grooming, dressing, meal preparation, and household chores. The most care is required in the severe stage.

Caregiving can be challenging in a number of ways. For people with Alzheimer’s disease, the growing loss of independence and privacy can be very frustrating, and even depressing. They may express their frustration by resisting help and insisting that they are still capable of doing things, even if they aren’t.

Some people with Alzheimer’s disease become suspicious of the very people who are trying to help them, especially those who are taking over financial responsibilities. This is understandable, given the mental changes that occur in people with Alzheimer’s.

When dealing with troublesome or confusing behaviors, it’s helpful to think about the situation from the perspective of the person with the cognitive impairment. This will help you find appropriate ways to respond that don’t exacerbate the problem. It will also help you come up with creative memory aids and other methods to help the person compensate for cognitive deficits.

Some resources, including books, manuals, and instructional videos, to help caregivers work with people with dementia are available from the Center for Applied Research in Dementia (see Appendix II: Resources, page 96). They developed memory techniques for people with Alzheimer’s disease based on an education system called Montessori, which was first developed for young children. Using these techniques, caregivers assist people with Alzheimer’s disease to make the most of the skills and habits they have retained, such as singing, playing a musical instrument, playing golf, or any other activity that engages the person. The key is to personalize the program by identifying activities, hobbies, and skills that the person enjoys and finding ways to continue these activities, possibly in a modified fashion. Memory exercises, such as sorting items into categories and matching colored balls to cups, may help to improve memory for some people.

Communication

As Alzheimer’s disease worsens, communication will become more difficult, but not impossible. It’s very important to talk with your spouse, parent, or friend and find out directly from them how you can assist them. This will be easier in the mild stage of the disease, but it’s important to continue communicating throughout the course of the illness. Even in the severe stage, a person with Alzheimer’s disease will still want to communicate.

Keep in mind that people with Alzheimer’s disease can generally comprehend more than they can express with language. If your loved one is having difficulty finding the right words to express a thought, it doesn’t mean she can’t understand you if you offer suggestions. Also, remember that spoken language is only one form of communication. Body language, tone of voice, and facial expressions are all aspects of communication that help get a message across.

Language difficulties will vary among people with Alzheimer’s disease. Some common problems include: being unable to find the right words, using the same words repeatedly, having difficulty forming sentences correctly, inventing words for familiar objects, and speaking less often.

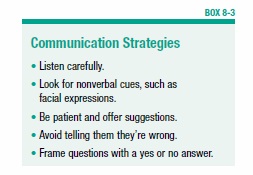

Given these problems, it often takes patience to understand what a person with Alzheimer’s disease is trying to convey. Listen carefully and try to get as many nonverbal cues as possible. Give the person time to think and describe what he wants. If he’s having trouble finding the right words, offer suggestions. But avoid telling him he’s wrong. Instead, repeat what you think he’s trying to say for clarification. If you still don’t understand, you can ask him to point or gesture. It’s also helpful to try to get a sense of the emotions behind the words. Sometimes the person’s feelings are more essential to what’s being communicated than the actual words.

When speaking to someone with Alzheimer’s disease, there are some ways to accommodate cognitive deficits. Speak in a calm voice, look the person in the eye, and use short and concise sentences. The person may forget what you’ve just said, so repeat yourself patiently when necessary. When giving the person directions, break up the task into one-step instructions. Tell them one step at a time. Frame questions so that they require only a yes or no answer. For example, don’t say, “What would you like for dinner?” Instead, say, “Would you like chicken or fish for dinner?” (See Box 8-3, “Communication Strategies”)

Avoid dictating to the person or overloading her with information. And don’t argue or criticize. This can cause confusion, fear, and anxiety.

If the person with Alzheimer’s disease has an angry outburst, don’t take it personally. This is often caused by feelings of frustration. Try to determine the cause of the frustration, and reassure the person as much as possible. Tell her not to worry about something she’s forgotten to do or her inability to find a misplaced item. Using kind words, tell her she’s not alone and that you are there to help her.

In the later stages of the disease, communication remains important, even though verbal skills are considerably impaired. Sharing time with nonverbal activities, such as listening to music, dancing, looking at photographs, or holding hands, may substitute for conversation.

Sometimes communication is hindered by poor vision or impaired hearing. Make sure the Alzheimer’s patient has her vision and hearing regularly tested, and that she gets glasses or a hearing aid if necessary.

Memory and Reminiscence Aids

Memory aids are generally helpful in the mild stage of Alzheimer’s disease. There are no standard aids that work for everyone. A person with Alzheimer’s disease will probably have to try out different memory tricks to see what helps.

Some people carry around a notebook with the names and phone numbers of people they often call. The notebook may also contain written reminders about chores, and instructions for doing tasks. Some people leave written reminders in strategic places around the house—for example, a note on the washing machine with step-by-step instructions for turning it on. Other people find that labeling things is helpful. Written signs may be placed around the house that read “refrigerator,” “sock drawer,” “bathroom,” etc. Also, place a calendar on the wall and mark off the days to make it easier to remember the day and date.

These memory aids will facilitate day-to-day tasks. It’s also important to have cues for remembering key people and events in the person’s life. Keep favorite photographs, newspaper clippings, and other things that are meaningful to the patient in prominent locations around the home, or on a bulletin board. You might also want to make a book with pictures and other mementos of important people and events from the past.

Bathing, Dressing, and Other Daily Activities

In the moderate and severe stages of the disease, a person with Alzheimer’s will need more help with basic hygiene and grooming, such as bathing, dressing, and dental care. This may be difficult. People with dementia resist assistance with personal care for a number of reasons. They might not want anyone intruding on their privacy. Also, the process of bathing and dressing can become too complicated and confusing. A person with Alzheimer’s might not remember when she last took a bath and insist that she doesn’t need one.

To smooth the way for a problem-free bath, try to prepare everything in advance. Run the bath water, have towels nearby, make the room temperature comfortable. Then give the person one-step instructions: “It’s time for a bath.” “Unbutton your shirt.” “Now take off your pants.” “Step into the bathtub.” If the person is self-conscious about being naked, respect her dignity. Allow her to hold a towel in front of her body when getting in and out of the tub or shower. Make sure there are non-slip adhesives on the floor of the tub and a grab bar to prevent falls.

Try to maintain the bathing routine the patient has already established. If she’s always bathed in the morning right before breakfast, keep to that schedule. If bathing becomes difficult, don’t require her to take a bath every day. Sometimes a sponge bath can substitute if you meet with insurmountable resistance.

When it comes to dressing, keep clothing choices simple. Help the person pick out coordinated clothes and then lay them out in the order they are to be put on. If necessary, give the person short instructions. When purchasing new clothes, think about comfort and simplicity. Shirts that button in the front are sometimes easier than pullover tops. If buttons and zippers are too difficult to manage, try replacing them with Velcro. Slip-on shoes are easier than shoes with laces.

People with Alzheimer’s also will eventually need help with oral hygiene. As the disease progresses, brushing and flossing teeth will become difficult. Rather than telling the person to brush her teeth, you may need to break it down into smaller steps: “Hold your toothbrush.” “Put toothpaste on your toothbrush.” You may need to demonstrate for her. Regular trips to the dentist continue to be important for a person with Alzheimer’s disease. Inform the dentist of the person’s condition ahead of time. You may need to search around to find a dentist who has experience working with people who have Alzheimer’s.

Wandering

Wandering is very common among people with Alzheimer’s disease, and it can be dangerous if the person wanders out of the house and gets lost. There are a number of strategies to deal with wandering. First, safeguard the house to make it less likely that the person will wander out the front door. For example:

- Place an alarm on the doorknob.

- Use childproof doorknob covers.

- Paint doors the same color as surrounding walls, making it more difficult for the person with dementia to identify the door.

- Install motion-activated alarms, which trigger an alarm if the person crosses an infrared beam.

Enroll the person in the Alzheimer’s Association’s “Safe Return” program. This program provides an identification bracelet, necklace, clothing tags, and wallet cards with contact information in case the person is found wandering. Make sure you have a recent photo available in case it is needed to help find someone who has wandered.

A high-tech solution to keeping track of a loved one with dementia is also available from the Alzheimer’s Association. Called Comfort Zone Check-In, this internet-based system provides information on a person’s location. The person wears or carries a GPS device, which receives signals from satellites or cell towers. Family members can access information about the person’s location from a website. They can request alerts when the person leaves a specified zone, or use the device only in an emergency. The device costs $100 to $200, and there is an additional monthly fee depending on the type of plan chosen.

Sometimes people wander because they’re bored, restless, or confused. One way to reduce wandering is to keep the person with Alzheimer’s engaged in activities. Go for walks or include the person in simple household chores, such as folding laundry.

Sleep Problems

People with Alzheimer’s disease are at increased risk of having disturbed sleep. They can become agitated and disoriented and stay awake all night. Medical experts don’t fully understand why sleep disturbances occur in Alzheimer’s disease, but there are some theories. It might simply be that the person hasn’t had enough activity during the day to be tired at night, or that older adults in general need less sleep than do younger people. Also, nighttime is associated with increased confusion (see ‘Sundowning,’ page 50), which leads to agitation that interferes with going to sleep. In addition, there may be a disturbance in the internal biological clock, which upsets the normal sleep/wake cycle.

To combat nighttime sleeplessness, keep the person with Alzheimer’s busy during the day. Refrain from offering caffeinated beverages in the evening. There are also medications that can help with nighttime agitation and sleep disturbances.

Researchers have looked into ways to readjust the sleep/wake cycle. Exposing the person to bright light early in the morning (thus cueing the body that it is morning and time to be awake), restricting the amount of time spent in bed, and using the over-the-counter remedy melatonin (a substance naturally produced by the body to regulate sleep/wake cycles) have been shown in studies to be helpful.

For safety, put nightlights in the bedroom and bathroom to avoid falls in the middle of the night. Restrict access to rooms by locking doors or installing safety gates. Install door sensors to alert people in the house that the person is awake.

If you want to coax the person back to sleep, speak calmly and remind him of the time. Ask if he’s up because he needs to use the bathroom or if he wants something. If he won’t go back to bed, but will fall asleep on a couch or in a lounge chair, allow him to do that.

Exercise

Exercise, such as brisk walking, has demonstrated benefits for both physical and mental health in people with dementia. It can reduce physical decline, frailty, and falls.

An analysis of 30 studies on the effects of exercise on people with cognitive impairment confirms this. Exercise was found to increase overall fitness and mental function, and to have a positive impact on behavior in people with dementia. One study showed that people with Alzheimer’s disease had a slower rate of decline in physical functioning if they engaged in an exercise regimen. This physical activity resulted in fewer falls, which translated to savings in healthcare costs. Therefore, regular walks of 20 to 60 minutes with a companion should be part of a routine for as long as the patient is able.

Maximize Existing Function

In part, a caregiver’s job is to help people with Alzheimer’s disease carry out tasks they can no longer manage. But it’s equally important to encourage them to continue doing things they are still able to do, and to find creative ways to help them compensate for cognitive deficits. For example, a person who’s lost the ability to communicate effectively with speech may be better able to communicate in other ways, such as through music or art. Music and art therapists can help bring out a patient’s musical or artistic side.

Caring for a person with Alzheimer’s disease can be a challenging and complex task, and caregivers need constant information and support. The Alzheimer’s Association offers support groups, workshops, and written materials for caregivers. The more acquainted you become with strategies for handling the changes that occur, the easier it will be for you to offer loving and supportive care.

The post 8. Caring for a person with Alzheimer’s Disease appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 8. Caring for a person with Alzheimer’s Disease »

Powered by WPeMatico