10. Practical Advice: Legal, Financial, Healthcare

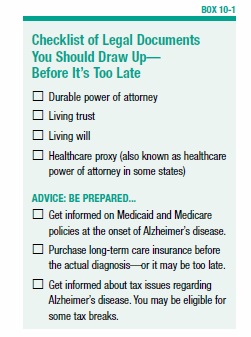

Receiving an Alzheimer’s diagnosis can be emotionally charged, and practical matters may be neglected. But at some point, early on, it will be necessary to make certain legal and financial decisions and to think about future care. Even if a person with Alzheimer’s disease is still capable of handling his own affairs, this will eventually change. Making legal and financial decisions early allows the person to actively participate in the planning of his or her own future. The decisions need to be set down in legal documents at a time when the person is still mentally competent enough to make decisions (see Box 10-1, “Checklist of Legal Documents You Should Draw Up—Before It’s Too Late”). Having a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease does not, by itself, mean that a person is incapable of making fundamental decisions. But there will come a time when the person’s decision-making ability will end.

Legal Planning

Start by consulting a lawyer who is familiar with trusts, estates, and laws pertaining to Medicare/Medicaid. Ask for a referral to someone who is experienced in elder or geriatric law. Your local Commission on Aging or your local Alzheimer’s Association chapter may be able to help as well. You need to have a will, and you will have to establish procedures for how financial and healthcare decisions will be made. Laws vary from state to state. If you’re helping a relative who lives in another state, retain a lawyer who has expertise in the laws of the state in which the person with Alzheimer’s lives.

Many people choose to grant “power of attorney” to a trusted family member or friend, who will take care of legal and financial transactions. However, a simple power of attorney is not enough because it becomes void when the person granting it is mentally incapable of making decisions. Therefore, the situation requires “durable power of attorney.” This authorizes the designated person to act on behalf of someone who is unable to make his or her own decisions.

You might also want to consider setting up a living trust. Assets are put into a trust, and a trustee (an individual or bank) will be responsible for managing the trust when the individual is no longer able.

When it comes to making arrangements for future medical decisions, you have basically two options: a healthcare proxy (also called a power of attorney for healthcare) and a living will. A healthcare proxy is a person you designate to make decisions on your behalf if you can no longer speak for yourself—often the same person to whom you would give durable power of attorney. This includes making decisions about medical treatment and eventually end-of-life decisions, such as whether to use a respirator to prolong life. When choosing a healthcare proxy, make sure it is someone you trust, and that he or she is willing to accept the responsibility. Also, have a conversation with your proxy and family members about your wishes.

A living will enables you state your wishes about medical care in advance, in the event that you later become unable to communicate. This is more limited than naming a healthcare proxy, because it is very difficult to anticipate specific health problems in advance. But a living will may be used to make your wishes clear about the use of artificial life support systems. The laws about living wills vary from state to state, so check with your lawyer to determine how best to express your wishes for future medical care.

If the proper legal documents are not set up before the person becomes mentally incompetent to sign them, it is necessary to go to court to have a judge appoint someone to act as guardian. The guardian then has the legal authority to make certain decisions on the patient’s behalf. This process is time-consuming and costly, and it involves a court proceeding before a judge. It can be avoided with some advance planning.

Financial Planning

Once Alzheimer’s disease worsens, the ability to handle finances deteriorates. Additionally, providing care for a person with Alzheimer’s disease is often costly. When considering the management of your financial affairs and the payment for your care, you should discuss the options with an attorney, a financial planner or an accountant—someone well versed in Medicare and Medicaid rules and regulations.

Begin with an assessment of your personal assets, including your financial resources and sources of income. Resources include bank and credit union accounts, investments (stocks and bonds), life insurance, health insurance, and real estate. Sources of income may be from salary, retirement benefits, Social Security, veterans’ benefits, rental income, interest, and dividends. Next, list any financial liabilities, such as loans, credit card debt, home mortgage, and property and income taxes.

You may want to arrange for the direct deposit into your savings or checking account of as many income sources as possible. To arrange for direct deposit of government funds (for example, Social Security and veterans’ benefits), file an authorization form, which you can pick up at most banks.

A joint bank account in the names of both the person with Alzheimer’s and the person who will be handling the finances is one way to simplify matters. However, there is a potential drawback. Although a joint account is a useful way to access another person’s resources, it may cause complications if you apply for Medicaid or other benefits. Government programs assume that all money in a joint account belongs to the person applying for the benefit.

The durable power of attorney, described earlier, is probably the best option for turning over the management of financial affairs. The agent, who acts on behalf of the person with Alzheimer’s disease, is authorized to deal with a wide range of financial matters, from managing bank accounts to selling assets.

To ease some of the financial burden, a few tax breaks exist for people with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers. An accountant can help you figure out your eligibility. For example, you may be entitled to a tax credit for part of the cost of a home attendant. If you claim the person with Alzheimer’s disease as a dependent, you may be able to deduct some medical expenses from your income tax.

Paying for Healthcare

The costs of caring for a person with Alzheimer’s disease are often high. There are some potential resources to help defray costs. These include Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance.

Medicare

Medicare covers all people 65 and older who are receiving Social Security retirement benefits. It pays for hospital care, a portion of doctor’s fees, some prescription drug costs, and some other medical expenses. For example, it covers physical and speech therapy and part of the cost of mental healthcare.

For dementia patients, Medicare will pay for physical, occupational, and speech therapy if the patient’s doctor deems these services necessary. Medicare will also cover psychotherapy or behavior management therapy provided by a mental health professional if this type of therapy is deemed to be reasonable and helpful.

Medicare does not cover adult day care, 24-hour personal care in the home, or room and board in an assisted-living facility or nursing home. The exception is care received after a hospital stay of three or more days. In this case, Medicare will pay for home care or care in a skilled nursing facility, but only for a limited time.

Medicare prescription drug coverage is provided by private insurance companies. Medicare beneficiaries must choose a plan and pay a monthly premium. All Medicare drug plans cover the costs for cholinesterase inhibitor drugs (Aricept, Exelon, Razadyne) and Namenda, in addition to antidepressants, antipsychotics, and anticonvulsants.

Medicaid

Medicaid will cover the cost of long-term care for a person with Alzheimer’s disease who meets the requirements. The laws are different, depending on the state in which you live, but benefits can include adult day care, respite care, home care, hospital care, and nursing home care. However, because it is a welfare program, the person with Alzheimer’s disease must have minimal income and assets to qualify. Some people divest themselves of their assets in order to qualify for Medicaid. If you choose to do this, there will be a period of time (up to three years) during which Medicaid will not pay for your nursing home care. Before divesting your assets, consult with an attorney or financial planner who understands the Medicaid laws in your state.

Other Financial Help

Veterans and their spouses, widows, children, or parents may be eligible for some medical benefits from the Department of Veterans Affairs. These benefits can include adult day care, home care, outpatient care, hospital care, and nursing home care. Contact the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (800-827-1000) for more information.

It’s possible to purchase long-term care insurance (nursing home insurance) from many insurance companies. These policies differ, but many are set up to pay a predetermined amount of money for each day a person is cared for in a long-term care facility. There can be deductibles, waiting periods, benefit time limits, and exclusions. Review several different plans before selecting one, and read the policy carefully before signing up. You typically must purchase long-term care insurance in advance of a disability. Once a person is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, obtaining long-term care insurance is difficult, because the disease is considered a pre-existing condition, and the policy probably won’t cover it.

The post 10. Practical Advice: Legal, Financial, Healthcare appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 10. Practical Advice: Legal, Financial, Healthcare »

Powered by WPeMatico