1. What is Alzheimer’s Disease?

Just about everyone experiences some memory lapses as they age. You may forget the name of someone you just met or not remember where you parked the car. Most memory slips like this can be overcome with memory tricks or by being more organized (such as always putting your glasses in the same place). Normal memory problems related to aging are discussed in Chapter 2.

For some people, problems with memory and thinking become increasingly worse, and seriously affect daily life. When this happens dementia is a likely cause. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common of several causes of dementia. A condition called mild cognitive impairment falls between normal forgetfulness and dementia.

Mild Cognitive Impairment

Some older adults have problems with memory, language, and other mental functions that are more pronounced than normal age-related changes but that don’t fulfill the criteria for dementia. This condition is called mild cognitive impairment (MCI). If only memory is affected, the condition is called amnestic MCI. But people with MCI may also have problems with other types of mental function, such as language and problem solving. For people with MCI, these problems are noticeable but they don’t seriously impact day-to-day functioning. When they are tested, people who have MCI remember less of a paragraph they have read or details of a simple drawing they have seen compared to people with normal age-related memory changes.

MCI can be, but is not always, a transitional state between normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Some people with MCI do not get worse and do not develop dementia, and some may even get better. Researchers are looking for specific characteristics that indicate a person with MCI is on the way to developing dementia.

Dementia

The term dementia refers to a severe decline in mental ability. People with dementia have impairments in the brain that affect memory and other types of mental functioning, such as reasoning, judgment, language, and abstract thinking. These problems seriously interfere with daily life. Unlike with age-related forgetfulness, the memory and thinking problems of dementia make normal daily activities like cleaning, organizing, preparing meals, doing household chores, and handling finances increasingly difficult and ultimately impossible. The ability to engage in day-to-day tasks at home, at work, or in social situations become severely diminished over time.

Different causes of dementia can have slightly varying symptoms. They can also overlap. Many people with dementia have more than one type, which is called mixed dementia. In fact, it’s now believed that many people with Alzheimer’s disease also have vascular dementia.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease, which accounts for about 60 to 80 percent of all cases of dementia in the United States, is well known as a memory-robbing disease. But, like with other forms of dementia, people with Alzheimer’s disease also have difficulty with other vital mental functions, like language, judgment, and problem solving. They have changes in personality, mood, activity level, and perceptions of the immediate environment. The changes are subtle at first and become worse over the years. Eventually people with Alzheimer’s disease must depend on others to care for them (the changes in mental function are described in greater detail in Chapter 6.

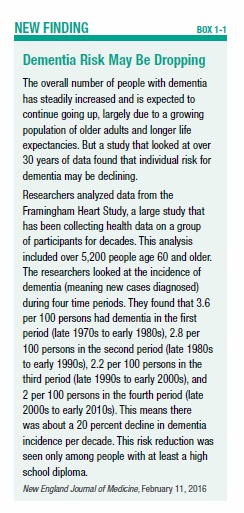

More than five million Americans are living with Alzheimer’s disease, the sixth leading cause of death in the United States. While the total number of people with the disease continues to steadily climb, the individual risk for Alzheimer’s disease may be declining. This was the finding of a study that looked at three decades of data (see Box 1-1, “Dementia Risk May Be Dropping”).

The growth in the overall number of people with dementia is largely due to the increasing population of people over age 65 and longer life expectancies. But when the researchers looked at the number of new cases within certain time periods, they found a different story. The incidence of dementia in people over age 60 was nearly four per 100 persons in the years from the late 1970s to the early 1980s. In the years starting in the early 2000s and going to the early 2010s, this had dropped to two per 100 persons. The reason for this drop is not known. It may, in part, relate to improvements over the past decades in the control of cardiovascular risk factors, like high blood pressure and cholesterol, which also raise risk for dementia. Education may also play a role, as the declines were observed in people who had at least a high school diploma (see Chapters 3 and 4 for more on risk factors for dementia).

Alzheimer’s disease mostly strikes after age 65, but it can also occur as early as age 30 in people with a rare form of hereditary Alzheimer’s disease (see page 18, “Genetically Determined Alzheimer’s Disease”). About five percent of people with Alzheimer’s disease have the hereditary form that can occur at a younger age.

Eleven percent of Americans aged 65 and older have Alzheimer’s disease, and about one-third of people ages 85 and older have it. Most people who have Alzheimer’s disease (81 percent) are age 75 or older. More women than men have Alzheimer’s disease, and the fact that women tend to live longer, on average, has been proposed as the reason. Almost two-thirds of all Americans with Alzheimer’s disease are women.

Other Causes of Dementia

The second most common type of dementia is vascular dementia. This can occur as a result of damage to blood vessels in the brain that reduces or blocks blood flow. Blocked or diminished blood flow prevents oxygen and vital nutrients from reaching portions of the brain. When major blood vessels are obstructed a stroke can occur, which usually causes obvious symptoms (weakness, numbness of the face, arms, or legs, or trouble speaking). It’s also possible to have minor strokes that are barely noticeable at the time (called transient ischemic attacks, or TIAs). The damage from strokes, even a succession of small ones, can lead to vascular dementia.

Other causes of dementia are frontotemporal dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, Huntington’s disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and normal pressure hydrocephalus. Dementia can also occur in people with Parkinson’s disease or alcoholism. Many people have more than one form of dementia—for example, a combination of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia, or Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies.

Brain Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease

The brain—by far the most complex organ in the body—contains about 100 billion specialized cells called neurons (see Box 1-2, “Neurons”). Neurons are clustered into distinct regions of the brain, each having specialized functions. For example, a region called the hippocampus plays a critical role in memory. Regions of the brain communicate with each other via an extensive two-way network of neurons. This interaction produces all of the functions of the brain, from thoughts, feelings, and memories, to movement and even breathing.

Damage to the brain—from strokes, head injuries, dementia, or other causes—can interfere with normal brain functioning. What aspect of function is affected depends on the type of damage and where in the brain it occurs.

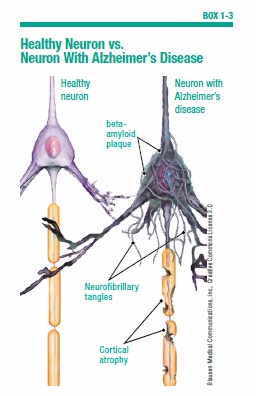

Alois Alzheimer, who identified the first Alzheimer’s patient in 1906, found two distinctive features when he performed an autopsy on the brain of a patient who had symptoms of dementia before she died. He discovered that nerve cells in certain areas of the brain were gummed up by a sticky material called amyloid plaque. Inside the cells, he found twisted threads called neurofibrillary tangles (see Box 1-3, “Healthy Neuron vs. Neuron With Alzheimer’s Disease”).

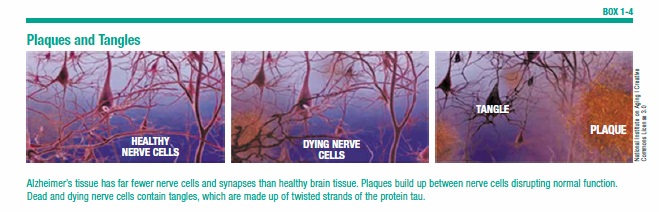

The presence of these plaques and tangles distinguishes Alzheimer’s disease from other forms of dementia (see Box 1-4, “Plaques and Tangles”).

Plaques and tangles show up first in the regions of the brain responsible for memory. As the disease progresses, these plaques and tangles rob cells in crucial brain areas of the ability to function. Key brain cells eventually die, which accounts for the permanent problems with memory, thinking, and behavior.

In addition to plaques and tangles, other abnormalities are seen in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease. These include inflammation, and oxidative damage to brain cells (from highly reactive forms of oxygen).

Many questions remain unanswered about the relationship of the plaques and tangles to the disease. For example, do plaques form first, which cause tangles to form, which then leads to the development of Alzheimer’s disease? Or, do the tangles occur first? Or, does some other physiologic event happen that triggers the formation of plaques and tangles? These questions have become imperative to answer because researchers now believe that understanding the earliest brain changes is the key to unlocking the mystery of Alzheimer’s disease and possibly preventing it.

Amyloid Plaques

Amyloid plaques are a sticky byproduct of a substance called beta-amyloid. Beta-amyloid is a small section of a larger protein called amyloid precursor protein (APP), which exists inside neurons. Under normal circumstances, APP appears to aid in the growth and maintenance of neurons. It stimulates the development of nerve paths. Intact nerve paths are essential for the brain to function properly. Through a process not yet fully understood, the APP can get snipped into smaller pieces, like taking a long strand of ribbon and cutting it into smaller sections. Sometimes it gets clipped into harmless pieces and sometimes it gets clipped in such a way that it forms beta-amyloid. Scientists have identified the enzymes that act like scissors, snipping APP into the beta-amyloid fragments.

The short beta-amyloid strands, intermingled with portions of neurons and other cells, clump together and eventually form sticky deposits called plaques. Plaques are found in the spaces between the brain’s neurons. In people with Alzheimer’s disease, these plaques form first in areas of the brain responsible for memory and thinking. The plaques displace healthy neurons and may kill them. Research is underway to better understand the biological mechanisms of APP, in the hope of discovering a way to stop it from breaking down into the detrimental beta-amyloid.

Neurofibrillary Tangles

Neurofibrillary tangles are dense proteins within neurons that injure the cells. These tangles are twisted threads, the major component of which is a protein called tau. Normally, tau has a beneficial function. But in people with Alzheimer’s disease, the tau protein has gone through a chemical change that prevents it from acting normally. The tau threads become twisted up with one another, forming tangles. As a result, the neuron loses the ability to function well, and it ultimately dies.

Lost Connections

As plaques and tangles become more numerous, they damage neurons to the point where they can no longer communicate with one another. Neurons communicate via chemicals called neurotransmitters, which carry signals from one cell to another. It is the intricate interconnection of billions of neurons communicating via these signals that regulates all the functions of the brain, from generating thoughts to controlling bodily movements.

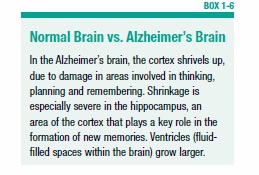

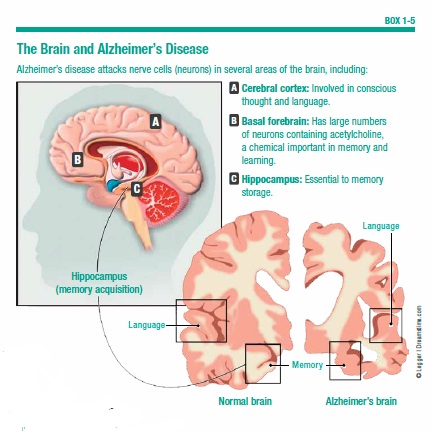

Eventually, the plaques and tangles cause neurons to die, and vital connections are lost. At first, the loss of neurons primarily affects the parts of the brain responsible for short-term memory (the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex), leading to short-term memory failures (see Box 1-5, “The Brain and Alzheimer’s Disease”). Later, the areas of the brain that control language, attention, and reasoning (in the cerebral cortex) are affected. Damage caused by Alzheimer’s disease can spread to other parts of the brain, leading to greater and greater disability. Over time, the brain shrinks dramatically as more and more neurons die (see Box 1-6, “Normal Brain vs. Alzheimer’s Brain”).

Later, the areas of the brain that control language, attention, and reasoning (in the cerebral cortex) are affected. Damage caused by Alzheimer’s disease can spread to other parts of the brain, leading to greater and greater disability. Over time, the brain shrinks dramatically as more and more neurons die (see Box 1-6, “Normal Brain vs. Alzheimer’s Brain”).

Scientists don’t fully understand the exact sequence of biological events that leads up to Alzheimer’s disease, yet there are several hypotheses. It is believed that the plaques, tangles, and other brain changes of Alzheimer’s disease begin long before memory loss and other cognitive problems become noticeable. This is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 11.

The post 1. What is Alzheimer’s Disease? appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 1. What is Alzheimer’s Disease? »

Powered by WPeMatico