4. Treatment for COPD

Even though COPD cannot be cured, it can be treated. Treatment is aimed at reducing symptoms, preventing the disease from getting worse, improving the ability to exercise, preventing and treating complications, and preventing and treating exacerbations.

For those with COPD who are current smokers, the most important first treatment will be to quit (see page 36). Smoking cessation helps to slow down the disease, especially in the early stages. People with COPD should also reduce their exposure to secondhand smoke, and occupational sources of lung irritants (like dust and chemicals), as well as indoor and outdoor air pollutants. When outdoor air quality is poor, persons with significant COPD should stay indoors to help reduce symptoms (see Box 4-1, “Minimizing the Effects of Outdoor Air Pollution”)

In people with COPD, the parts of the lungs damaged due to emphysema cannot be restored. Therefore, treatment is aimed at improving the function of the parts of the lungs that are still working, and reducing inflammation in the lungs.

The mainstay of COPD treatment involves drug therapy with bronchodilators to open the airways. Anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics may also be used. Regular physical activity is important to maintain lung function. For more severe disease, a specialized exercise program called pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to improve the ability to exercise and engage in basic daily activities with less shortness of breath. In patients with more severe disease, oxygen therapy is often required. Some people with advanced COPD may be candidates for lung volume reduction surgery, which may relieve symptoms and can improve quality of life; or may be candidates for lung transplantation. Everyone with COPD should receive immunizations for influenza and pneumonia.

Drugs to Treat Obstructive Airway Diseases

Drug therapy will be part of the treatment for just about everyone who has an obstructive airway disease, including COPD and asthma. Drug regimens are generally centered on two types of medicines: bronchodilators, which open narrowed airways, and anti-inflammatory drugs (called corticosteroids) to reduce inflammation in the lungs. Various combinations of these medications often are used.

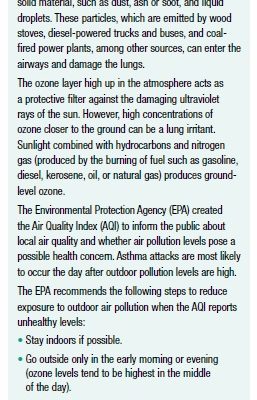

Bronchodilators

Bronchodilators expand the airways, making it easier to breathe and therefore easier to go about daily life. There are two main types of bronchodilators (see Box 4-2, “Bronchodilator Drugs”)—beta-agonists and anticholinergics—and each is available in a short-acting and a long-acting formulation. A third type of bronchodilator, theophylline, is an older drug that is used less frequently.

Beta-agonists

Beta-agonists activate a receptor called the beta-2 receptor on muscles surrounding the bronchial tubes. This causes the muscles to relax, and the airway to dilate. Short-acting beta-agonists include albuterol (Ventolin, ProAir, Salbutamol, Proventil, VoSpire ER), levalbuterol (Xopenex HFA), and pirbuterol (Maxair Autoinhaler). These medications start to work quickly (within minutes), and last about four to six hours. Long-acting beta-agonists, which are often called LABAs, include salmeterol (Serevent), formoterol (Foradil, Perforomist), arformoterol (Brovana), indacaterol (Arcapta Neohaler), and olodaterol (Striverdi Respimat). These medications take longer to begin working (about 20 minutes), but last up to 24 hours.

The long-acting beta-agonists salmeterol, formoterol, and arformoterol are taken twice a day. Indacaterol and olodaterol are taken once a day.

Possible beta-agonist side effects include headaches, nervousness, dizziness, and shakiness. Each of the medications has other possible side effects. If side effects occur, they often last only a short time and diminish or resolve completely once the medication is used regularly. If they persist, consult your doctor—a different medication or a lower dose may be prescribed.

Anticholinergics

Anticholinergics block a receptor in the lung to prevent constriction of the airways. This allows the airways to remain open. The short-acting anticholinergic drug ipratropium (Atrovent) starts to work within 15 minutes, and lasts for six to eight hours. The long-acting anticholinergic drugs tiotropium (Spiriva) and umeclidinium (Incruse Ellipta) take about 20 minutes to start working, and last for 24 hours. The long-acting anticholinergic drug aclidinium (Tudorza Pressair) takes about 10 minutes to start working, and lasts 12 hours.

Possible side effects of ipratropium are coughing, headaches, nausea, heartburn, diarrhea, urinary retention, and constipation, among others. Tiotropium can cause dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, stomach pain, and other side effects. Possible side effects of umeclidinium include colds, infections in the upper respiratory tract (sinuses, ears), a cough, and joint pain. Aclidinium can cause fever, headache, muscle aches, sore throat, stuffy or runny nose, unusual tiredness, and other side effects. If these symptoms occur, they are generally not serious and should diminish or go away completely with ongoing use of the medication. If any side effect is severe or does not go away, a different medication may be needed.

Inhaled Medications

While bronchodilators (both beta-agonists and anticholinergics) can be taken in different ways (orally, intravenously, inhaled), the preferred method for delivering the drugs in people with obstructive airway disease is through inhalation. Using an inhaler device, the drug is breathed in. A drug delivered in this way quickly goes to the airway, where it is needed. There are generally fewer side effects with inhaled medications than there are with pills.

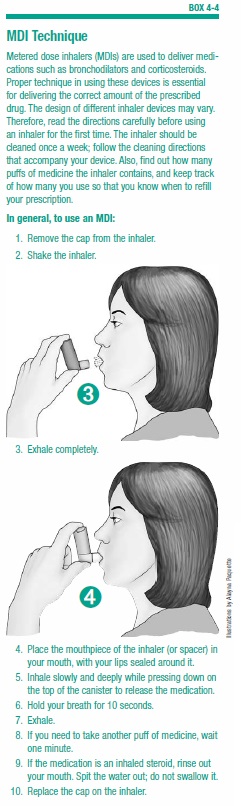

To ensure that the correct amount of drug is delivered, it is very important to use proper inhaler technique. Poor technique can result in too little drug reaching the lungs, as well as more side effects due to the drug being deposited in the mouth or the back of the throat.

Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Anti-inflammatory medications are drugs that reduce inflammation. Corticosteroids are the anti-inflammatory drugs most frequently given to people with COPD or asthma to reduce swelling in the bronchial tubes. They can be taken in tablet, liquid, injected, or inhaled form.

Corticosteroids do not work as quickly as bronchodilators—it can take up to a week to notice the effect. The pill form acts faster than the inhaled version, but often causes more side effects.

Inhaled Corticosteroids

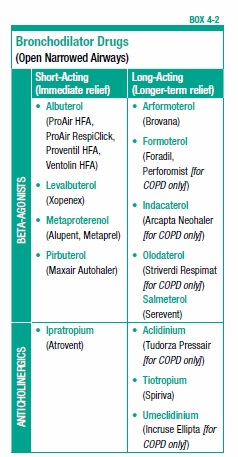

Most people with obstructive airway disease who take corticosteroids will use the inhaled form. Inhaled corticosteroids include triamcinolone (Azmacort), beclomethasone (Vanceril, Qvar, Beclovent), flunisolide (AeroBid, AeroBid-M), fluticasone (Flovent), and budesonide (Pulmicort). Using an inhaler device, the medication is delivered directly to the lungs. Very little medication travels through the bloodstream, which means there will be few side effects. In commonly used doses, inhaled steroids are safe to use over the long term. Possible side effects are a sore throat, hoarse voice, and oral candidiasis (a yeast infection in the mouth). Candidiasis can be avoided by rinsing your mouth with water after each use of the inhaler, or by using a spacer (see Box 4-3, “Metered-Dose Inhaler [MDI] Spacer”).

As with bronchodilators, proper technique using the inhaler device is critical to the successful delivery of the correct dose of the drug.

Oral Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids in pill form are generally reserved for treating acute exacerbations of COPD or asthma. The effects are felt within a few hours of taking the drug: Breathing will become easier, coughing and wheezing will ease, and mucus production will lessen. Even though they have such pronounced effects, oral corticosteroids are generally only used for a short period of time (a few days to a few weeks). This is because in addition to reducing inflammation, corticosteroids have other effects on the body that can cause unwanted and sometimes severe consequences.

Taken by pill in moderate-to-high doses for months or years, corticosteroids can cause problems such as bruising of the skin, cataracts, bone thinning (osteoporosis), muscle weakness, hair loss, growth of facial hair in women, mood changes, and weight gain. A person who uses oral steroids for long periods of time may also be susceptible to developing high blood pressure and/or diabetes. When oral steroids are used for more than a few weeks, the body becomes accustomed to the drug and it cannot be stopped abruptly without adverse effects. Therefore, anyone who takes oral steroids for several weeks or more must taper off the drug rather than stopping it abruptly.

Common corticosteroids taken in tablet form are prednisone (Deltasone), and prednisolone (Medrol).

Types of Inhalers

Inhalers deliver bronchodilator or corticosteroid medication as a spray, mist, or fine powder. Three types of inhalers are available: a metered dose inhaler (MDI), a dry powder inhaler (DPI), and a nebulizer.

Metered Dose Inhalers

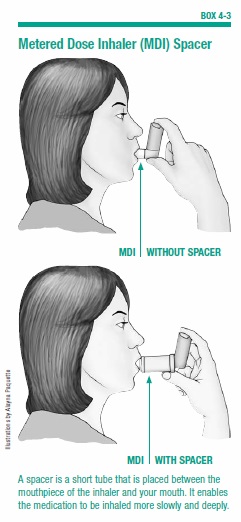

An MDI is a small, pressurized canister with a mouthpiece and a metering valve that contains medication. The patient places his or her mouth over the mouthpiece, and then inhales while pushing down on the top of the canister to deliver a precise dose of the medication.

The proper technique for using an MDI inhaler is described in Box 4-4, “MDI Technique.” Several common mistakes can lead to too little or too much medication being delivered. For example, some people exhale before the end of the spray, or inhale after the medication is sprayed. Other mistakes include inhaling through the nose instead of the mouth, squeezing the canister twice but only inhaling once, or forgetting to take the cap off the mouthpiece.

Many people find it helpful to use a spacer device with their MDI to improve drug delivery. A spacer is a short tube that is placed between the mouthpiece of the inhaler and your mouth (see Box 4-3, “Metered Dose Inhaler [MDI] Spacer,” on page 26). The medicine enters the tube, and from there it can be inhaled more slowly and deeply. This results in more effective delivery of the medicine to the lungs.

The medication in the MDI canister is suspended in a mixture of substances. One of these is a propellant, which squirts the mixture out of the device and gives it enough momentum to get down into the lungs. The mix also contains preservatives, flavoring agents, and chemicals that help to disperse the drug throughout the lung.

Each inhaler has different directions for washing, drying the mouthpiece, and priming. It’s important to follow the instructions that come with the inhaler your doctor has prescribed.

Dry Powder Inhalers

DPIs are similar to MDIs but they don’t contain a propellant. Using a DPI requires inhaling more deeply and quickly to propel the medicine out of the device and into the lungs. These are somewhat easier to use, as they don’t require the coordination of taking a breath while actuating the device with your hand.

To use a DPI, simply place your mouth tightly over the mouthpiece and inhale quickly. A DPI inhaler should not be shaken before use (like an MDI); nor are spacers used.

Nebulizers

Inhaled medications like bronchodilators and corticosteroids can also be delivered via a nebulizer. A nebulizer is a machine that turns the liquid form of a drug into a fine mist that is then inhaled through a mouthpiece or facemask. Nebulizers are often used for treating very young children who have asthma. They are also used for older children and adults who have more severe lung disease, or who have difficulty using MDIs or dry powder inhalers.

The long-acting bronchodilator formoterol (which is a beta-agonist) is available for use in a nebulizer. This drug is an alternative to MDI and DPI inhalers for COPD patients who may have difficulty using inhaler devices easily or correctly.

Treatment Options for COPD

Almost every person with COPD will be prescribed a short-acting bronchodilator (either a beta-agonist, an anticholinergic, or a combination of both—see page 24) to use on an as-needed basis to relieve shortness of breath, coughing, wheezing, and other symptoms. Some people will also need a long-acting bronchodilator and/or an anti-inflammatory drug. Your doctor will work with you to figure out the right drugs and combinations of drugs to relieve your symptoms.

Mild COPD

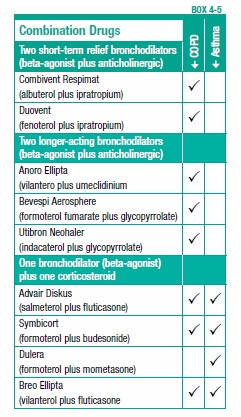

For a person with mild COPD who has occasional symptoms, a short-acting bronchodilator alone may be sufficient to manage the condition. The physician may also prescribe two short-acting bronchodilators—a beta-agonist plus an anticholinergic—to use together. To simplify this regimen, a combination of a short-acting beta-agonist plus a short-acting anticholinergic is available in one inhaler (see Box 4-5, “Combination Drugs”). This is a combination of albuterol plus ipratropium (Combivent Respimat, DuoNeb).

Moderate-to-Severe COPD

As lung function deteriorates, additional treatments will likely be necessary, including the following:

Bronchodilators

For people with moderate or severe COPD, for whom the symptoms tend to occur more frequently, one or more long-acting bronchodilators will be added to the regimen. These drugs are taken on a regular schedule. For example, the drugs salmeterol, formoterol, arformoterol, and aclidinium, which last for 12 hours, will be taken twice a day. The drugs tiotropium, umeclidinium, olodaterol, and indacaterol, which last 24 hours, will be taken once a day. If acute episodes of breathlessness or coughing occur while taking these medications, a short-acting bronchodilator (such as albuterol) can be used to quell those episodes.

For patients with more severe COPD, some combination of drugs (such as two long-acting bronchodilators) will likely be used. Drugs that combine two longer-acting bronchodilators (a beta-agonist and an anticholinergic) in one inhaler include umeclidinium plus vilanterol (Anoro Ellipta), glycopyrrolate plus formoterol (Bevespi Aerosphere), and indacaterol plus glycopyrrolate (Utibron Neohaler).

Corticosteroids

The combination of drugs may include a corticosteroid (see page 25) to reduce inflammation. When corticosteroids are used, they are generally given in the inhaled form. Corticosteroids in pill form are not recommended for long-term use in people with COPD because of the potential side effects.

Inhaled corticosteroids are recommended for people with moderate or severe COPD who do not get sufficient relief from bronchodilators or who experience frequent flare-ups (exacerbations) of symptoms. Inhaled corticosteroids have been shown to reduce flare-ups; however, there is some debate about whether their benefits outweigh certain risks that accompany their use.

Some studies have found that use of inhaled corticosteroids, with or without a bronchodilator, increases the risk for developing pneumonia. One study found that despite the possibility for increasing the occurrence of pneumonia, use of inhaled corticosteroids may decrease the risk of dying from pneumonia. Further research is needed to clarify these issues, and patients should discuss any concerns with their physician.

Combination Corticosteroid/Bronchodilator

For people prescribed long-term use of both a long-acting bronchodilator and a corticosteroid, products are available that combine these two drugs in one inhaler. Combination products include formoterol plus budesonide (Symbicort), salmeterol plus fluticasone (Advair), and vilanterol plus fluticasone (Breo Ellipta).

Roflumilast

Another drug for COPD is roflumilast (Daliresp), a once-a-day drug to decrease the frequency of exacerbations or worsening of symptoms in severe COPD. The drug is for people with chronic bronchitis, and is not intended to treat emphysema. Roflumilast works through a different mechanism than bronchodilators and anti-inflammatory drugs.

Expectorant Medications and Cough Suppressants

People with COPD often use expectorants, which can be obtained in cough medicines such as guaifenesin (Robitussin), to thin mucus and help to bring it up. However, there is little evidence to show that these medicines are helpful for people with COPD. In addition, cough suppressants should be avoided. Even though coughing can be a bothersome symptom, it has the important function of helping to clear mucus. This means that suppressing a cough may increase the risk of lung infection.

Immunizations

Influenza (“flu”) is a nuisance for young and healthy people—but for people with obstructive airway diseases, it can be very serious and potentially life threatening. The same applies to pneumonia, although this can be treated with antibiotics. Fortunately, vaccines are available to protect against influenza and some forms of pneumonia. It is extremely important that everyone with obstructive airway disease follow the recommended vaccination schedule, or their doctor’s advice.

Flu Vaccine

People with COPD or other lung problems should receive an influenza vaccination once a year. Flu season runs from November to March, and the ideal time to get a flu shot is in October or November (see page 65).

Pneumococcal Vaccine

The pneumococcal vaccine protects against the bacteria that is the most common cause of pneumonia (Streptococcus pneumoniae). There are now two forms of pneumococcal vaccine, the Pneumovax and the Prevnar 13. It is recommended that all adults over age 65 receive a pneumococcal vaccination (see page 72). Unlike the flu shot, which must be given every year in the fall, pneumococcal vaccination provides protection for at least five years. It can be given at any time of the year.

The pneumococcal vaccine is advised for all people with COPD age 65 and older. It also may be given to people with COPD who are younger than age 65 and have severe or very severe disease (FEV1 less than 40 percent of predicted). It also may be recommended for people with asthma who are younger than age 65.

Treatment for Flare-Ups

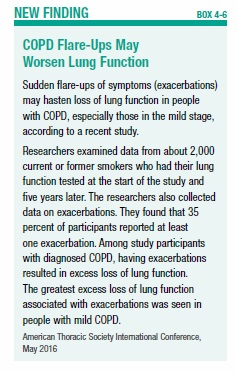

An exacerbation is a sudden flare-up of COPD symptoms beyond normal day-to-day variations. Increased breathlessness along with wheezing, chest tightness, increased cough and sputum, change of the color of sputum, and fever are common features of an exacerbation. It may warrant either a short-term or long-term change in medication, and serious exacerbations may require hospitalization. A recent study found that exacerbations of COPD may speed up loss of lung function, especially for people with mild COPD (see Box 4-6, “COPD Flare-Ups May Worsen Lung Function”).

Three types of medications often used to treat exacerbations are bronchodilators, corticosteroids, and antibiotics. When oral corticosteroids are used for an acute flare-up of symptoms, they will most likely be taken for five days.

The most common cause of an exacerbation is a lung infection, which may be signaled by increased amounts of mucus production. In this case, antibiotics may be used—however, before prescribing an antibiotic the doctor may send a sample of the sputum for analysis to determine if the infection has a bacterial or viral cause, since antibiotics are only effective against bacteria.

One study found that people with COPD who received antibiotics within two days of hospitalization for an exacerbation had better outcomes than those treated later or not at all. A review of several studies concluded that a short course (five days) of antibiotics is just as effective as taking antibiotics for longer than five days. Some physicians recommend using antibiotics on a long-term basis to prevent infection in COPD—however, this remains controversial.

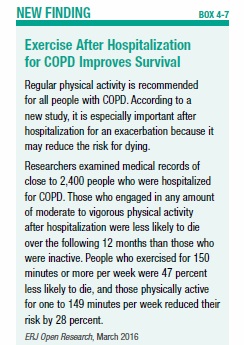

A recent study found that engaging in regular exercise following a hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation extends life (see Box 4-7, “Exercise After Hospitalization for COPD Improves Survival”).

Where you live may make a difference in frequency of exacerbations. One study found that people with COPD who live in communities that ban smoking in public places were 22 percent less likely to be hospitalized for COPD than those living in communities that do not have such laws (most hospitalizations are for flare-ups of the disease).

Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Therapy

Younger adults who have emphysema as a result of a hereditary deficiency of alpha-1 antitrypsin (see page 15) may be treated with alpha-1 antitrypsin augmentation therapy. Alpha-1 antitrypsin is a protein that circulates in the blood. Augmentation therapy uses a concentrated form of this protein, which has been removed from donated blood and purified.

This therapy cannot reverse damage that has already been done to the lungs, but it has been shown to slow down the further decline of lung function. The therapy must be taken for life, and is very expensive. It must be administered by a healthcare professional in a doctor’s office or hospital clinic, or through home infusion services. The costs may be covered by private health insurance policies, but criteria for coverage can vary widely—before beginning therapy, check with your insurance company. For people age 65 and older, Medicare covers at least part of the cost.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

A very helpful addition to drug therapy for people at all stages of COPD is a specialized program called pulmonary rehabilitation. Pulmonary rehabilitation is a series of educational and structured exercises that allow people to make the most of the remaining capacity of their lungs. People with COPD who engage in these programs have less shortness of breath, an increased ability to exercise, better quality of life, and less frequent hospitalizations than similar COPD patients who do not participate in pulmonary rehabilitation.

People with COPD tend to decrease their physical activity, since shortness of breath makes exertion more and more difficult. Decreased activity can start a vicious cycle of progressive deconditioning, and this leads to worsening of symptoms and more breathlessness, with less and less physical activity. Pulmonary rehabilitation is aimed at breaking that cycle.

A pulmonary rehabilitation program is more than an exercise program, although exercise is the most important component. In addition to exercise training, the program may include:

- Nutrition counseling

- Education about your condition

- Breathing strategies

- Energy-conserving techniques

- Help with smoking cessation

- Education about medications and how to take them

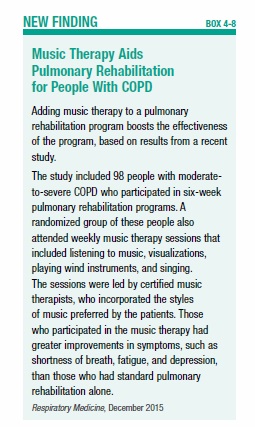

One study found that including music therapy in a pulmonary rehabilitation program provided added benefit (see Box 4-8, “Music Therapy Aids Pulmonary Rehabilitation for People With COPD”).

Most pulmonary rehabilitation programs last six weeks or longer. The exercises learned during the program should be continued at home once the program ends. Studies have found that pulmonary rehabilitation benefits are generally sustained for up to 18 months after the program ends, especially if the exercise training is maintained. One study found that people in the earlier stages of COPD derived greater benefits than those in the later stages. Although those with less-advanced COPD had better results, those with severe COPD also had improved ability to exercise and less shortness of breath. This research suggests that when it comes to pulmonary rehabilitation, the earlier it is done the better—however, all of the patients were helped by the program.

There are many pulmonary rehabilitation programs around the country. Your physician can most likely refer you to one; alternately, contact the American Lung Association or the American Association for Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, which has a searchable online directory of pulmonary rehabilitation programs (see Resources, page 80). Health insurance may or may not cover pulmonary rehabilitation: You’ll need to check with your insurance carrier. The guidelines for Medicare coverage of pulmonary rehabilitation vary from state to state—check with your physician or pulmonary rehabilitation provider to obtain the guidelines in your state.

Oxygen Therapy

People with severe COPD may have low levels of oxygen in their blood (a condition called hypoxemia). This may cause increased difficulty breathing, and further impair the ability to exercise. Low oxygen levels may also cause fatigue, memory loss, headaches in the morning, depression, and confusion. Over time, chronically low oxygen levels also can cause heart failure. Oxygen therapy can help people with hypoxemia.

Interestingly, in many people with COPD there may be few, if any, symptoms that can specifically be linked to hypoxemia. To determine whether a person with COPD has hypoxemia, a physician will perform either an arterial blood gas test (see page 21) or pulse oximetry. In pulse oximetry, a noninvasive probe is attached to the finger, ear, or forehead to measure the amount of oxygen in the blood. The pulse oximetry may be done both at rest and while the patient is walking, since the oxygen level in the blood is often only low during activity.

Oxygen therapy usually is given only to people with very severe (stage IV) COPD (see Box 3-2, “Stages of COPD,” page 22). In stage IV COPD, the airflow is severely limited and the amount of air that can be blown out in one second (FEV1) is less than 30 percent of what would be expected for someone without lung disease. For these people, long-term use of supplemental oxygen for more than 15 hours each day can prolong life, and improve quality of life. Oxygen therapy also may reduce shortness of breath during exertion, which makes it easier to perform basic daily activities. Oxygen therapy also may improve mental functioning, reduce depression, and aid the heart.

Supplemental oxygen may be used continuously (24 hours) or periodically, such as only during exercise or overnight. The primary goal of using supplemental oxygen is to ensure adequate delivery of oxygen to preserve the function of vital organs.

Normal atmospheric air contains about 21 percent oxygen. The amount of oxygen breathed into the lungs can be increased by providing an additional amount of pure oxygen that is inhaled with each breath. The physician will prescribe a specific amount of supplemental oxygen, and provide instructions on when and how long it should be used, as well as which delivery method will be used. There are three methods for delivering oxygen, as explained below. With each system, the oxygen is breathed in through a mask or a nasal tube (cannula).

Compressed Oxygen Gas

Compressed oxygen gas is contained in tanks or cylinders of varying sizes. Large stationary tanks are used inside the home, while smaller, more portable tanks can be used on brief forays outside the home (they usually have enough oxygen to last a few hours).

Liquid Oxygen

A liquid form of oxygen is created by cooling oxygen gas. When the liquid is warmed, it turns back into a gas that can be inhaled. Like compressed oxygen gas, liquid oxygen systems include a large tank for use in the home. The system also includes a small portable canister for use outside the home (this canister is filled with liquid oxygen from the indoor tank). One disadvantage of liquid oxygen systems is the tendency for the liquid to evaporate over time.

Oxygen Concentrator

An oxygen concentrator is an electric device that takes air from the room and separates the oxygen from other gases. The oxygen is then available to be inhaled through a mask or nasal cannula. This system does not require that tanks of liquid or gaseous oxygen be continuously refilled. The supply of oxygen is unlimited, and the device is small enough to be moved from room to room. Most oxygen concentrators require a continuous electrical source, and must be plugged into an electrical outlet. However there are newer, more portable oxygen concentrators that operate on battery power and may be used for exercise or travel.

Surgery

Lung Volume Reduction

Selected patients with advanced COPD may be candidates for a surgical procedure that can ease the effort of breathing, and make walking and other daily activities more feasible. In this procedure, called lung volume reduction surgery, the parts of the lung that are most heavily damaged by emphysema are removed. As described previously, the destruction of alveoli in people with emphysema causes air to get trapped in the lungs. As a result, the lungs become enlarged (hyperinflated). Enlarged lungs can crowd the chest cavity and flatten the diaphragm, making it more difficult to breathe. Removing these hyperinflated portions of the lungs has the effect of improving lung function and quality of life.

The surgery won’t cure emphysema, but it may help to relieve symptoms and may prolong life in some patients. However the surgery only helps a minority of patients with emphysema. For this reason, it is very important that patients who are considering lung volume reduction are carefully evaluated by a surgeon who is experienced in this highly specialized surgery.

The traditional approach to lung volume reduction surgery involves opening the chest with an incision through the breastbone to gain access to the lungs. Some years ago, a minimally invasive technique was developed. With this procedure, several small incisions are made on both sides of the chest. A thin tube with a video camera on the end is inserted through one of the incisions. This allows the surgeon to see inside the body on a video monitor. Surgical instruments are inserted through the other incisions to remove the hyperinflated lung. Regardless of the procedure used, you will most likely stay in the hospital for five to 10 days after the surgery. Because of the risk of surgery there is interest in trying to develop lung volume reduction techniques that do not require surgery, but instead use bronchoscopy (a procedure that allows your doctor to look at your airway through a thin viewing instrument called a bronchoscope). At present these procedures are considered experimental and are not widely available.

Medicare covers traditional lung volume reduction surgery for people who meet certain criteria, and requires that anyone contemplating the surgery first complete a certified pulmonary rehabilitation program.

Lung Transplantation

Lung transplantation may be considered for people with severe COPD who are otherwise healthy. This procedure is generally reserved for people who have end-stage lung disease, but no other significant health problems. The criteria generally include an FEV1 of less than 20 percent of what would be predicted for someone without lung disease, as well as very low oxygen levels or very high carbon dioxide levels.

For patients with emphysema, either one or both lungs may be transplanted. The procedure generally results in improved lung function and better quality of life. However, there are risks involved in the surgery, and lung transplant recipients must take drugs to suppress their immune system for the remainder of their lives. These drugs are necessary to prevent the body from rejecting the new organ.

Smoking Cessation

Stopping smoking is an essential step for preventing and treating COPD—but as just about anyone who has quit smoking or tried to quit smoking can attest, this advice is easy to give but not so easy to accomplish. People with obstructive lung disease have a powerful incentive to quit smoking, yet many continue to light up. A CDC study found that 46 percent of adults age 40 and older who have asthma or COPD still smoke.

Cigarette smoking is a powerful addiction, and simply knowing the laundry list of its ill effects rarely is enough to make smokers quit the habit. About 70 percent of adult smokers report that they want to quit completely, but very few people succeed in permanently quitting on their first attempt. Quitting smoking requires, first and foremost, motivation. But it also requires understanding what you’re up against and getting the right type of help.

Nicotine Addiction

Nicotine is an addictive substance that acts on regions of the brain that produce pleasurable effects, and it produces these effects very quickly. Nicotine is carried in cigarette smoke into the lungs, where it is absorbed from the alveoli into the bloodstream. From there, it reaches the brain within about seven seconds—an extremely efficient mode of drug delivery. It also clears from the brain very quickly. In the brain, nicotine binds to receptors called nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, which results in a release of brain chemicals called neurotransmitters. The primary neurotransmitter released from intake of nicotine is dopamine, which is believed to be linked to the region of the brain responsible for pleasurable feelings, such as those connected with food and sex. Other neurotransmitters released when nicotine binds to nicotinic receptors produce effects that also reinforce tobacco use. These include stimulation, arousal, improved memory and attention, reduced anxiety and stress, relaxation, improved mood, faster reaction time, and appetite suppression.

Many smokers come to depend on smoking to reliably produce these effects. However, because nicotine levels don’t stay elevated in the blood for very long, the effects are short-lived and more cigarettes are needed to achieve them.

Upon quitting, many smokers report withdrawal symptoms, such as depressed mood, insomnia, irritability, frustration, anger, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, restlessness, decreased heart rate, and increased appetite or weight gain. These are relieved with smoking, making it especially difficult to quit.

The physiologic addiction to nicotine is only part of the story: There also is a large psychological and behavioral component. Smoking becomes a habit, and as such, smokers often associate smoking with certain activities or moods. For example, some people smoke a cigarette after a meal or with a drink, when they feel stressed, or to perk themselves up when they feel down. Smokers also come to associate the pleasurable effects of smoking with the ritual of smoking. They may enjoy just holding a cigarette, the act of lighting it, or the smell and taste of the smoke.

Getting Help to Quit

Because smoking is associated with physiological, behavioral, and psychological factors, all three must be addressed when attempting to quit. For people who want to quit, studies have shown that some combination of counseling, social support, and pharmacologic therapies usually is necessary. It will probably take more than one try to quit for good, but the benefits are worth it.

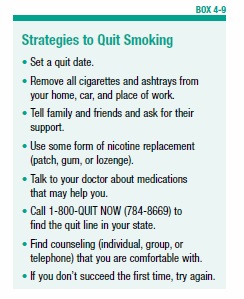

It all starts with the decision to quit. Guidelines published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) recommend beginning by setting a firm quit date, preferably within two weeks. Some helpful strategies for quitting are in Box 4-9, “Strategies to Quit Smoking.”

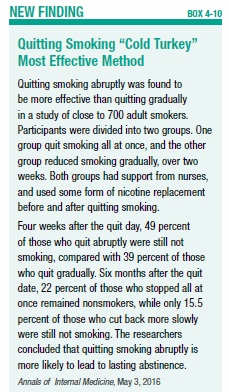

Enlisting the support of family and friends is essential. Some form of counseling—either an individual or group counseling program—is advised. Internet-based chat rooms can also be helpful. Quit lines have been set up in many states (www.smokefree.gov; 1-800-QUITNOW) to connect smokers to relevant resources. Some smokers have been helped to quit with acupuncture or hypnosis. One study found that the best way to quit smoking is “cold turkey”—that is, stopping abruptly rather than gradually cutting down (see Box 4-10, “Quitting Smoking ‘Cold Turkey’ Most Effective Method”).

For some people age 65 and older, Medicare Part B will cover smoking cessation counseling. The coverage is limited to those who smoke and have a disease or adverse health effects linked to tobacco use. Two smoking cessation attempts are allowed each year, and for each attempt Medicare will pay for up to four counseling sessions.

Breaking the smoking habit will most likely require coming up with new problem-solving and stress-reducing techniques to replace smoking. For example, it can be helpful to identify situations or activities that increase your risk for smoking, and discuss new types of coping skills with a counselor or fellow smokers who are quitting. Also try to minimize time spent with smokers, to reduce temptation.

Medications That Can Help You Quit

To address the nicotine addiction, several types of pharmacologic therapies are available to relieve withdrawal symptoms. Many of these products are nicotine replacement therapies.

Nicotine Replacement

These are available in skin patches, gums, lozenges, inhalers, and a nasal spray. The patch, gum, and lozenges can be obtained without a prescription. Nicotine gum is not chewed like regular gum—in order for the nicotine to be absorbed, the gum must be chewed a few times, and then placed and held between the cheek and gum.

The nicotine patch maintains a steady blood level of nicotine. This avoids the ups and downs of nicotine levels during smoking, and disrupts the “crave-and-reward” cycle. A step-down program is usually recommended when using the nicotine patch. This program starts with a higher dose (21 mg/day), which is reduced to a moderate dose (14 mg/day), and finally a low dose (7 mg/day).

E-cigarettes contain nicotine, and some smokers switch to these vapor-producing devices to help them quit tobacco cigarettes. The effectiveness of nicotine replacement therapies such as the gum and patch are established. E-cigarettes are still being studied as an aid to quitting, and two questions remain unanswered. First, are e-cigarettes safe? Second, are they an effective tool for quitting? One study found that smokers who used e-cigarettes were actually less likely to quit smoking than those who never used them.

Bupropion (Zyban)

Another drug that is sometimes used for smoking cessation is bupropion (Zyban), which requires a doctor’s prescription. Bupropion has been shown to help eliminate withdrawal symptoms, but it appears that the drug works best when used in conjunction with one of the nicotine replacement therapies.

Varenicline (Chantix)

This is another drug available by prescription only. This drug works by binding to some of the nicotinic receptors, which blocks nicotine from binding to these receptors. This results in a reduction in the craving for nicotine, and decreases the pleasurable effects of smoking. Studies have shown the drug to be generally effective at helping people to quit smoking; however, some people who take the drug experience severe changes in mood and behavior. The manufacturer advises stopping the drug and contacting a healthcare provider immediately if agitation, depressed mood, changes in behavior, or suicidal thoughts or behavior occur. Some people who use varenicline have a decreased tolerance to alcohol, and get drunk more easily—therefore, people who use the drug are advised to decrease the amount of alcohol they consume.

There are numerous resources to help people quit smoking. Some of these are listed in the Resources section (page 80). If you try and fail, don’t be discouraged: You are not alone. Perhaps you just need to try a different technique until you find one that works for you.

Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation

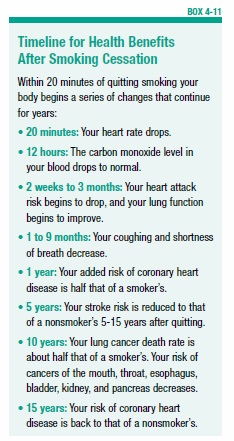

Some of the benefits of quitting occur relatively quickly, while others can take 10 or more years (see Box 4-11, “Timeline for Health Benefits After Smoking Cessation”). Soon after quitting, blood circulation and lung function begin to improve. Within one to two years, the risk for heart disease decreases. The risk for developing cancer declines with the number of years of smoking cessation.

A large study of more than 104,000 women quantified some of the risk reduction with smoking cessation:

- Those who quit smoking had a 13 percent reduced risk of dying from any cause within the first five years of quitting, compared with women who continued to smoke.

- The excess risk of death from any cause reached the level of never-smokers 20 years after quitting.

- Much of the reduction in risk of dying from heart disease was realized within the first five years.

- Five to 10 years after quitting, death from any type of lung disease was reduced by 18 percent, reaching the level of never-smokers after 20 years.

- About 64 percent of deaths among current smokers and 28 percent of deaths among former smokers were attributable to cigarette smoking.

- Lung cancer mortality was reduced 21 percent within five years of smoking cessation, but it took 30 years to completely eliminate the excess risk.

Lifestyle Tips to Maintain Lung Function

In addition to quitting smoking and taking prescribed medications, people with COPD can take steps to improve their health and possibly slow down the damage caused by the disease. These include eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, special breathing techniques, and changes in day-to-day living, among others. Even staying cool can have important benefits: One study found that high indoor and outdoor temperatures were linked to more symptoms. Being in hot indoor environments also worsened lung function.

Healthy habits are recommended for everyone, but are especially necessary for those with chronic lung disease.

Eat Right

Your body needs the energy provided by food to function, and that includes breathing. In fact, oxygen is a necessary part of the process of breaking down food into energy (called metabolism). Energy, in turn, is needed for the process of breathing. For people with COPD, difficulty breathing may make it difficult to eat properly, creating a downward cycle that can lead to malnourishment and even greater breathing problems.

About one-third of people with COPD are malnourished, and experience weight loss. Malnutrition can worsen lung function and also compromise the immune system. A compromised immune system can render a person with COPD susceptible to infections and other illnesses.

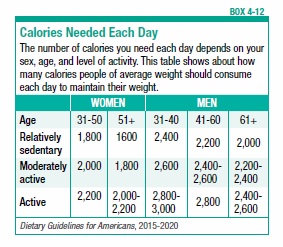

It is extremely important for people with COPD to consume the recommended number of calories, and try to maintain a healthy weight. If you are underweight, it means your body has fewer stores of energy to draw from. Being overweight also can be problematic, since carrying extra weight means the heart has to work harder, which makes breathing more difficult.

A well-balanced diet that provides an adequate number of calories is necessary for good health. The recommended caloric intake varies by age and level of activity (see Box 4-12, “Calories Needed Each Day”).

Keep in mind that people with COPD expend extra energy in the simple act of breathing. For a person with COPD, the act of breathing may burn 10 times as many calories as it does for someone without lung disease. This means that even more calories may be required to maintain proper weight.

Foods to Prioritize

The source of calories is important. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has established sound nutrition guidelines, which are available at www.choosemyplate.gov. You might also consider consulting a registered dietitian who specializes in COPD and can work with you to develop an individualized food plan.

The USDA recommends consuming foods and beverages that are rich in nutrients and come from the basic food groups. Try to avoid foods with little nutritional value that supply only empty calories. The diet should emphasize fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and dairy products. The diet should also include protein from lean meats, poultry, and fish, along with beans, eggs, and nuts. Try to limit the amount of saturated fats, trans fats, cholesterol, salt (sodium), and sugar. Sodium is particularly problematic because it can cause fluid retention, which can interfere with breathing.

One study found that people with COPD who ate a healthy diet that included fish, grapefruit, bananas, and cheese had better lung function and fewer symptoms than those who did not eat these foods. The researchers noted that these particular foods may not by themselves be the key to improved health—rather, eating them indicates the person most likely eats an overall healthy diet that includes fish, fruit, and dairy products.

Foods to Avoid

Avoid foods that cause gas or bloating, as this can make breathing more difficult. Gas-producing foods include broccoli, cauliflower, beans, and carbonated beverages.

Other Diet Tips

Drink plenty of fluids, which help to thin mucus and thus make it easier to cough up. Try for six to eight glasses (eight fluid ounces each) per day. Water, milk, and fruit juice are the best sources, but coffee, tea, and soft drinks also count. Alcoholic beverages, such as wine and beer, contribute to fluid intake, but should be consumed only in limited amounts.

If breathing problems make eating difficult, try eating four to six small meals a day rather than three large ones. You might also try eating the largest meal early in the day, so that you have more energy for the rest of the day.

Take your time preparing meals, and choose foods that are easy to prepare. You don’t want to expend too much energy making a meal, only to have little energy left to eat it. Eat slowly, in a relaxed setting. Digestion requires energy, so wait an hour or more after eating before engaging in activities.

Exercise Regularly

People at all stages of COPD experience a decline in their ability to engage in physical activity over time as the disease worsens. But while it may seem difficult to exercise when breathing is a problem, a program of regular exercise can actually improve lung function. It also keeps muscles strong, and improves overall health. A recent study of people with COPD found that those who got no exercise at all were less able to be physically active and had weaker muscle strength compared to people who were at least somewhat physically active.

If you feel daunted by the idea of exercising, keep in mind that the level of exertion required is relative to your health and ability. You don’t need to be an athlete to benefit from exercise—in fact, you should begin by having a discussion with your doctor to determine the most appropriate type of exercise and level of intensity.

If you’ve been in a pulmonary rehabilitation program, continue the exercises on your own after finishing the program. If you haven’t been in one of these programs, be sure to increase your physical activity slowly from your present level. Walking and swimming are good ways to get exercise without overexerting yourself. Try to walk a little farther and for longer periods each day. Try to work up to 20 to 30 minutes of physical activity three to five times a week. The key is to do it on a regular basis (daily, or at least several times each week). Research has shown that increasing physical activity decreases hospitalizations due to exacerbations of COPD. One study found that people with COPD who engaged in any regular exercise were about one-third less likely to be readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of being discharged. The benefit was greatest for those who exercised 150 minutes or more a week.

Before beginning an exercise, warm up your muscles by doing some stretches. If walking is your chosen activity, start at a slow pace and gradually walk faster. It may help to walk or exercise with friends, making it a social occasion. Be sure to go at your own pace, and don’t compare yourself to anyone else. Keep a diary to record your exercise goals and track your progress.

Control Your Breathing

Breathing techniques, such as pursed-lip breathing and diaphragmatic breathing, may help to make the most of every breath you take. Talk to your physician or respiratory therapist about these techniques to find out if they might be useful for you.

Air that gets trapped in the lungs can cause shortness of breath. Air trapping can occur from breathing too fast, or because of narrowed airways and damaged alveoli. Pursed-lip breathing slows the pace of breathing and increases air pressure in the lungs, which helps the airways to stay open. If you feel short of breath from exertion, stop for a few minutes and practice pursed-lip breathing to get fresh air flowing into your lungs (see Box 4-13, “Pursed-Lip Breathing”).

Diaphragmatic breathing makes more efficient use of the diaphragm to facilitate deeper breathing. The diaphragm is a dome-shaped muscle in the abdomen which is involved in the mechanical process of breathing (see page 8). In people with COPD, the diaphragm and other muscles involved in breathing can weaken. Using a diaphragmatic breathing technique (see Box 4-14, “Diaphragmatic Breathing”) can help to strengthen these muscles, slow down your breathing rate, increase your blood oxygen levels, and allow you to use less effort to breathe.

Breathe Clean Air

Keep the air in your home as clear of irritants as possible. For example:

- Don’t smoke, and don’t allow anyone else to smoke in the house.

- Keep all fumes and strong smells out.

- If you must have painting done, stay out of the house until it is finished.

- Avoid smoke from wood fires.

Travel Comfortably

Having a chronic lung disease such as COPD may require making special arrangements for traveling, especially travel by airplane. Those who require oxygen therapy will first need to obtain permission to fly from their physician. They must also notify the airline well in advance of travel, to arrange for use of oxygen during the flight.

Some people who don’t require oxygen therapy at home may need supplemental oxygen while flying. This is because the air pressure inside an airplane cabin is lower than it is on the ground, especially when the airplane is taking off and landing. Low air pressure decreases the amount of oxygen in the air. People without lung disease can accommodate to the changes in air pressure, but for a person with severe COPD, even a small change in air pressure may cause an exacerbation of symptoms.

Always discuss air travel plans with your physician. Blood oxygen measurements will likely be needed to determine whether supplemental oxygen will be required. The doctor will also need to provide a letter to the airline. During the flight, the oxygen will be provided by the airline (there will likely be a fee for this service). Passengers are not allowed to bring their own liquid or gas oxygen canisters on board an airplane, but some airlines will allow patients to use their own portable concentrators during flights. Empty cylinders and equipment likely are allowed only as checked baggage.

Information about which airlines allow use of oxygen on flights, along with their policies, is available from the Airline Oxygen Council of America.

Relax and Take Care of Yourself

Anxiety, stress, and fatigue are common in everyday life and can lead to health problems even for otherwise healthy people. For people with COPD they can exacerbate the condition, leading to worsened lung function, infections, and other health problems (see Box 4-15, “Know Your Limits”).

Coping with COPD may feel overwhelming at times. Sharing feelings and concerns with loved ones and asking for their help may ease some of the burden. Joining a support group for people with COPD may be even more helpful. The American Lung Association is a good resource for finding a local support group.

The post 4. Treatment for COPD appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 4. Treatment for COPD »

Powered by WPeMatico