3. Diagnosis of COPD

The main diagnostic tools for COPD are pulmonary function tests. These tests, which are also used to diagnose asthma (see page 45) and many other lung diseases, measure the ability of the lungs to hold air, to move air in and out, and to move oxygen into the blood.

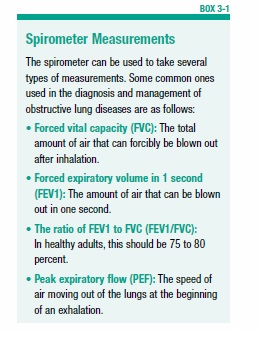

The values obtained from most of the pulmonary function tests are expressed in percentages, and are compared to values expected for a person of similar age, height, ethnicity, and gender who does not have any lung disease. This comparison is made because several factors can influence lung function. For example, lung function decreases as people age even if they have no lung disease. So, it is important to compare the test values to those of people with similar characteristics. For example, a spirometry reading may reveal an FEV1 (the amount of air that can be blown out in one second—see Box 3-1 for more details) of less than 80 percent of predicted (for a person of the same age with no lung disease). Such a result indicates impaired lung function, possibly due to COPD or asthma.

Pulmonary Function Tests

Spirometry

In a test called spirometry, the patient takes a deep breath in and then exhales as hard and as long as possible into a hose connected to a machine called a spirometer. The machine measures how fast air is blown out of the lungs, as well as the total amount of air inhaled and exhaled (see Box 3-1, “Spirometer Measurements”).

Bronchodilator Reversibility Testing

Another common diagnostic test is bronchodilator reversibility testing. For this test, the patient does a spirometry test and then takes a bronchodilator drug (see page 24) before taking the spirometry test a second time. Bronchodilators open up narrowed airways by loosening the muscles surrounding the airways. If the spirometry test improves after taking a bronchodilator, this suggests that the patient has asthma rather than COPD, since asthma is often reversible. But for people with COPD, airflow will continue to be limited even after taking the drug.

Peak Flow Meter

A simpler device for measuring how quickly air can be expelled from the lungs is a peak flow meter. Using this handheld device, the person inhales deeply and then blows as hard as possible into the device. If the airways are narrow or blocked, the peak flow will drop below normal. Peak flow meters are generally not recommended for diagnosing lung conditions—instead, they are used by people with asthma to monitor their condition over time, or to determine how well a particular medication is working.

Measuring Lung Volume

Another type of pulmonary function test measures lung volume. In people with COPD, air often gets trapped in the lungs. Having too much air in the lungs can make the lungs overly inflated (hyperinflated). To determine whether this is happening, a physician may perform one of two tests to measure lung volume:

Body Plethysmograph

In this test, the patient sits in a sealed, clear box, and breathes into a mouthpiece connected to a measuring device. Lung volume is determined by changes in pressure inside the box.

Helium Dilution or Nitrogen Washout

A second method for determining lung volume involves breathing nitrogen or helium gas through a tube. The concentration of the gas in a chamber attached to the tube is measured to estimate the lung volume.

Diffusing Capacity of the Lung for Carbon Monoxide

The destruction of alveoli in people with emphysema can impair the normal exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide. To estimate how well the lungs are able to move oxygen into the blood, a test called diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) may be performed. For this test, the patient inhales harmless gas that contains a small amount of carbon monoxide, holds his or her breath briefly, and then rapidly exhales into a tube. The exhaled gas is analyzed to determine how much carbon monoxide was absorbed by the lungs. This provides information about how quickly gas can move from the lungs into the bloodstream.

Impulse Oscillometry

Impulse oscillometry uses sound waves to detect airway changes that indicate obstructive lung diseases such as asthma and COPD. The patient breathes normally into a device that generates vibrations and calculates resistance to breathing. This technique may be used to diagnose airway disease in very young children, or in older adults with physical or intellectual impairments that make performing spirometry (which involves vigorously exhaling into a machine) difficult or impossible. It also may be used along with spirometry. Some studies suggest that impulse oscillometry may identify COPD earlier than is possible with spirometry.

Other Diagnostic Tests

Chest X-Ray

A chest X-ray generally cannot be used to diagnose obstructive lung disease, because only severe emphysema will be visible on a chest X-ray. However, your doctor may have you undergo a chest X-ray to see if your symptoms might be attributable to another condition, such as heart failure or another lung disease.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) is another type of imaging study that may be used for some patients. During a CT scan, thin X-ray beams rotate around the patient, creating a series of two-dimensional images. A computer turns these images into a three-dimensional image of the lung (or other organ). This test is better at detecting emphysema than chronic bronchitis or asthma. CT scanning is also an excellent way to diagnose bronchiectasis (see page 58). CT scanning is not generally used for an initial diagnosis of obstructive airway disease. It may be used to decide if a patient with COPD is a candidate for some types of lung surgery, or to diagnose bronchiectasis.

Arterial Blood Gas Test

For patients with advanced COPD, an arterial blood gas test may be performed. This measures the amount of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood. It is used to determine if there is too little oxygen in the blood (a condition called hypoxemia), or to detect the presence of too much carbon dioxide (called hypercapnia).

Diagnosing COPD

COPD and asthma (see page 45) share many of the same symptoms (primarily coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath), which occur because normal airflow into and out of the lungs is obstructed. This can make it difficult to distinguish the two conditions, especially in middle- and older-age adults, who have a history of smoking. Regardless of the age that these symptoms first appear, it’s important to make an accurate diagnosis, because treatment often differs for the two conditions.

The physician will perform a physical examination, take a detailed medical history, ask about smoking (in adults) and other lifestyle issues, and perform diagnostic tests.

A physician should suspect COPD in anyone with a history of smoking or exposure to environmental irritants who has any of the characteristic symptoms of COPD (chronic cough, sputum production, and shortness of breath with exertion). To make the diagnosis, the physician will perform a physical examination and evaluate the patient with spirometry and possibly other tests, as described above.

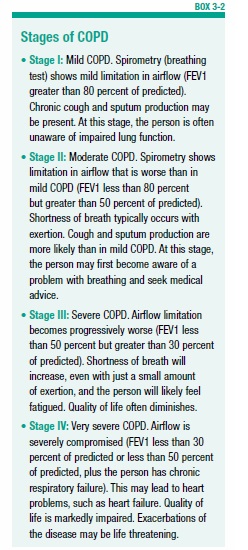

People with COPD have a decrease in FEV1 (the amount of air that can be blown out in one second). As the disease gets worse, the FVC (the total amount of air that can be exhaled after inhalation) also deteriorates compared to people of the same age with normal lung function.

Spirometry can detect COPD even before symptoms of the disease become apparent. Spirometry is used both to diagnose and to assess the severity of COPD. COPD is divided into four stages: mild, moderate, severe, and very severe (see Box 3-2, “Stages of COPD”). These classifications are based on increasing severity of airflow restriction and symptoms. The spirometry reading for FEV1 is generally used to determine the severity classification.

In addition to its use for diagnosing COPD and determining its severity, spirometry is also used to follow the progression of the disease.

For people younger than age 40 who have characteristic signs and symptoms of COPD, the physician will likely order a blood test to determine if the cause is alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (see page 15). The test also may be ordered for people with COPD symptoms who have a strong family history of COPD, or a family history of the enzyme deficiency.

The post 3. Diagnosis of COPD appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 3. Diagnosis of COPD »

Powered by WPeMatico