3. Know Your Cardiovascular Risk

You’ve taken pretty good care of yourself. You eat right, don’t smoke, and stay pretty active. You have no apparent signs of heart trouble, so you figure you’re at pretty low risk for a heart attack, stroke, or other cardiovascular event. Regardless of whether or not you’re doing all the right things, you still need to know just how healthy your heart and blood vessels are. After all, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the United States.

That’s why it’s important to understand the factors that increase your risk of cardiovascular events and also those that have a protective effect. Be sure to keep tabs not only on your cholesterol, but also your other cardiovascular risk factors so that you and your healthcare team can gauge (and reduce) your overall cardiovascular risk.

Your Heart at Risk

In addition to hyperlipidemia, these factors can increase your risk of cardiovascular disease, heart attack, and stroke:

Modifiable Risk Factors

Hypertension

Like hyperlipidemia, high blood pressure contributes to the atherosclerotic process. By exerting force against the artery walls, hypertension can damage the inner lining of your arteries, the endothelium. This damage allows cholesterol, fats, platelets (blood cells responsible for clotting), calcium, and other materials to accumulate in the artery wall. Over time, the artery thickens, narrows, and becomes more rigid, and blood flow is restricted.

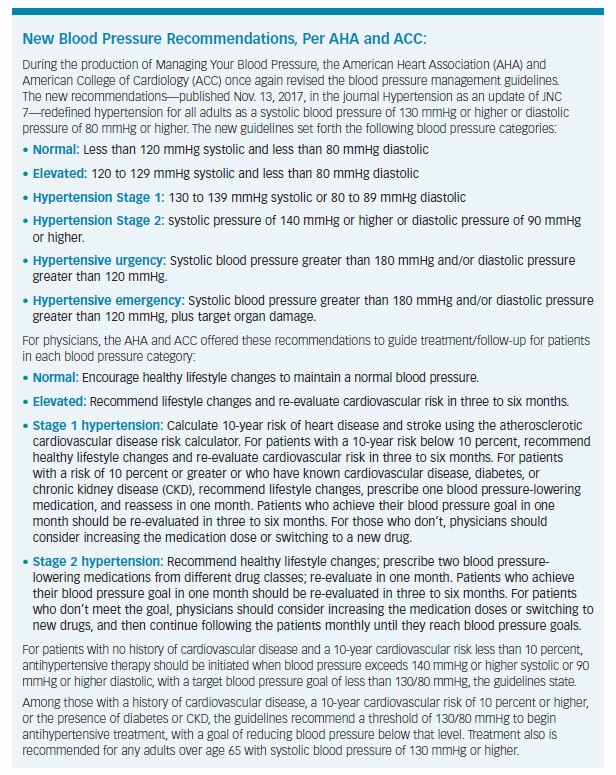

Most medical organizations, including the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, categorize blood pressure as follows:

- Normal: A systolic blood pressure (the top number in the reading) of less than 120 mmHg and a diastolic pressure of less than 80 mmHg.

- Prehypertension: A systolic blood pressure consistently ranging from 120 to 139 mmHg or a diastolic pressure consistently ranging from 80 to 89 mmHg; you’re at increased risk of hypertension if you don’t take action to control your blood pressure.

- Stage 1 hypertension: A systolic blood pressure consistently ranging from 140 to 159 mmHg or a diastolic pressure consistently ranging from 90 to 99 mmHg.

- Stage 2 hypertension: A systolic blood pressure consistently ranging from 160 mmHg or higher, or a diastolic pressure consistently ranging from 100 mmHg or higher.

In November 2017, the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACA) issued recommendations that involve a new threshold of 130/80 (see sidebar).

Experts also recognize hypertensive crisis, a sharp, rapid rise in blood pressure requiring immediate medical attention.

Diabetes

Diabetes—including the most common form, type 2 (adult-onset) diabetes—is a strong risk factor for cardiovascular disease. In fact, more than two-thirds of diabetes patients age 65 and older die from some type of heart disease, and 16 percent die from stroke, according to the American Heart Association.

The high blood-sugar levels associated with diabetes can, over time, harm your blood vessels, as well as the nerves that control your heart and blood vessels. Even prediabetes—elevated blood-sugar levels that have not crossed the threshold into type 2 diabetes—increases cardiovascular risk.

Physicians use several tests to measure blood sugar and diagnose prediabetes and diabetes:

- Fasting plasma glucose: A measure of your blood-sugar levels after fasting for eight hours or more. A reading of 100 to 125 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dl) indicates prediabetes, while 126 mg/dl or higher signifies diabetes.

- Oral glucose tolerance test: A measure of your blood-sugar levels before and two hours after drinking a sweetened beverage, to determine how you process glucose. A result of 140 to 199 mg/dl indicates prediabetes; 200 mg/dl or higher is diabetes.

- Hemoglobin A1C: This diabetes test, the newest of the three options, measures your average blood-sugar levels over the past two to three months. The test requires no fasting or consumption of a sweetened beverage. An A1C of 5.7 to 6.4 percent means prediabetes, while an A1C of 6.5 percent or higher indicates diabetes.

Tobacco smoke

Cigarette smoking is a major independent risk factor for coronary heart disease. It lowers HDL cholesterol levels, raises blood pressure, and increases the risk of blood-clot formation. Even exposure to secondhand smoke can contribute to cardiovascular disease: An estimated 22,700 to 69,600 premature deaths from cardiovascular disease each year are attributable to secondhand smoke, according to the American Heart Association.

Obesity

Carrying around excess weight? If you are, especially if your extra fat is concentrated around your waist, you’re at greater risk of suffering a heart attack or stroke, even if you don’t have high cholesterol, diabetes, or other cardiovascular risk factors. The good news is that losing just 5 to 10 percent of your body weight can help lower your cholesterol, blood pressure, and your cardiovascular risk.

A Sedentary Lifestyle

A sedentary lifestyle can cause declines in HDL cholesterol, contribute to rises in blood pressure, and lead you on the path to obesity and type 2 diabetes—all major risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

For overall cardiovascular health, most experts recommend getting a minimum 150 minutes, or 2½ hours, of moderate-intensity physical activity, 75 minutes of vigorous activity, or a combination of the two each week. For most people, moderate-intensity activities include brisk walking, biking, or swimming, while more vigorous activities include jogging, running, or playing singles tennis.

An Unhealthy Diet

A diet high in saturated and trans fats can increase LDL cholesterol; trans fats also reduce beneficial HDL cholesterol. Consuming too many of these fats along with added sugar (found in many processed foods, desserts, and many soft drinks) can further increase your cardiovascular risk by adding unwanted pounds to your waistline. Another dietary culprit is sodium: Eating too many sodium-rich foods can raise your blood pressure and increase your risk of hypertension.

Emotional Stress

Chronic stress and anxiety may directly increase the risk of coronary heart disease and can increase blood pressure by prompting your arteries to constrict. Indirectly, emotional stress can contribute to cardiovascular disease by prompting unhealthy behaviors, such as tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption, poor diet quality (eating “comfort foods”), and lack of exercise.

Alcohol in Excess

You might have heard that drinking alcohol, particularly red wine, in moderation may confer cardiovascular and other health benefits. But, if you don’t already imbibe, that doesn’t mean you should take up drinking to improve your heart health.

The key words here are “in moderation,” because, as with anything in life, you can get too much of a good thing when it comes to consuming red wine or any alcohol. Excessive drinking can contribute to high triglycerides, obesity, and atrial fibrillation (an irregular heart rhythm), increase blood pressure, and heighten the risk of stroke, cardiomyopathy, and heart failure. If you do drink, limit your alcohol consumption to no more than two standard drinks a day for men and no more than one drink a day for women. A standard drink equates to one 12-ounce beer, 5 ounces of wine, 1½ ounces of 80-proof distilled spirits, or 1 ounce of 100-proof spirits.

What Is Metabolic Syndrome?

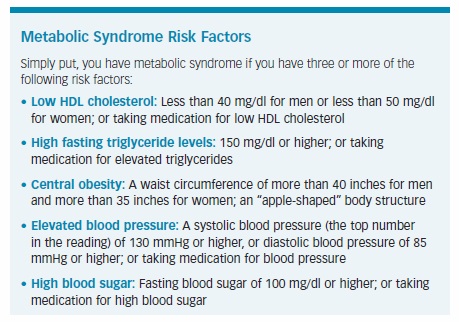

It has been called “insulin resistance syndrome” or the more enigmatic “syndrome X.” But, it is most commonly referred to as metabolic syndrome.

Regardless of its name, metabolic syndrome is synonymous with obesity and a greater risk of heart attack, stroke, and type 2 diabetes. In this age of fatty food and sedentary lifestyles, metabolic syndrome is growing along with the expanding waistlines of people worldwide, and it now affects more than one in three Americans, according to the American Heart Association (AHA).

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the United States is higher in Caucasians than in Mexican-Americans and African-Americans, while for women it’s more common among Mexican-Americans compared with their Caucasian or African-American counterparts, the AHA notes.

While having one risk factor, such as cholesterol abnormalities, can increase your odds of cardiovascular events, having multiple ones—as in metabolic syndrome—only heightens the risk (see sidebar).

Nonmodifiable Risk Factors

Age

Your risk of cardiovascular disease, and several of its risk factors, increases with advancing age. The American Heart Association (AHA) notes that the majority of deaths from coronary heart disease occur in people age 65 and older.

Gender

The risk of heart attack is greater in men than in women, and men usually experience heart attacks at a younger age. Although women’s risk of cardiovascular death rises after menopause, it still does not reach the risk level of men.

Race

African-Americans face a higher risk of heart disease than Caucasians, partly because they face a significantly greater risk of high blood pressure than people of any other racial background. Additionally, about one third of Hispanics will develop hypertension, and nearly half will contend with high cholesterol, according to the AHA. The risk of cardiovascular disease also is higher among American Indians, native Hawaiians, and some Asian-Americans, the AHA says.

Family History

If one or both of your parents or any siblings has had cardiovascular disease, heart attack, or stroke, especially at an early age, you may be at increased risk, as well. Your risk may be due to genetic factors, but it also may be attributable to environmental and lifestyle factors—for example, living in a family of smokers or poor eaters.

“Both the risk of heart disease and risk factors for heart disease are strongly linked to family history,” William Kraus, MD, of Duke University, said in an AHA statement. “If you have a stroke in your family, you are more likely to have one.”

Familial Hypercholesterolemia

Some people are essentially born with high cholesterol. They have familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), a genetic defect that prevents the liver from removing excess LDL cholesterol from the blood, and their elevated LDL only worsens over time. By far, the most common form is heterozygous FH, which occurs when the genetic defect is inherited from only one parent.

Among untreated adults with FH, LDL levels can eclipse 190 to 400 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dl) or higher, while children with FH often have LDL levels above 160 mg/dl, according to the Familial Hypercholesterolemia Foundation. Although lifestyle changes can help, patients with FH typically require medical therapy to control their LDL.

Men and women with FH face significantly increased risks of coronary heart disease and early heart attack, independent of other cardiovascular risk factors. The AHA notes that:

- Compared to men without FH, those with the disorder will develop coronary heart disease as much as 20 years earlier, and half of them will suffer a heart attack or angina before they reach age 50.

- For women, 30 percent with FH will have a heart attack before age 60, and their coronary heart disease develops up to 30 years earlier than it does in their non-FH counterparts.

In one analysis, researchers reviewed data from six study groups involving 68,565 person-examinations, including 3,850 patients with FH (defined as LDL cholesterol of 190 mg/dl or higher). Compared to the study participants with LDL levels below 130 mg/dl, those with FH were five times more likely to die from coronary heart disease or suffer a nonfatal heart attack, and about four times more likely to develop coronary heart disease or stroke, the study found (Circulation, June 29, 2016).

For years, FH was thought to affect only about one in 500 American adults. However, this thinking changed somewhat in 2016 with publication of a study showing that the prevalence of FH in Americans age 20 and older was about twice as high as once believed. Researchers examining data from a large nationwide survey found that FH may affect as many as one out of every 250 American adults, or about 834,500 people.

When considering race, the investigators found that FH affected about one in 249 Caucasians, one in 211 African-Americans, and one in 414 Mexican-Americans. Men and women were affected equally, and the risk of FH rose with age (one in 1,557 people in their 20s versus one in 118 people in their 60s) and increasing weight (one in 172 obese people versus one in 325 non-obese people), the study found (Circulation, March 14, 2016).

“It’s more common than we thought, and it’s important to look for it at a young age because someone with FH may have no symptoms until there is serious heart disease,” the study’s lead author, Sarah de Ferranti, MD, assistant professor of pediatric cardiology at Harvard Medical School and director of preventive cardiology at Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts, said in an AHA statement.

“A common story might be someone who develops chest pain or has a heart attack in their 30s or 40s, even though they look healthy, eat well, and are thin and fit.

“If you’re born with FH, you have lifelong exposure to high cholesterol, making your heart attack risk similar to someone decades older,” she continued. “If you know that somebody has had an early heart attack in your family, consider asking for everyone to be checked.”

Calculating Your Risk

If you don’t know your cardiovascular risk, have your physician calculate it to determine what you need to do to stay on the path to good heart health. Doctors can choose from an array of risk calculators, incorporating various combinations of risk factors, to estimate your cardiovascular risk over the next decade or more. Here’s a look at a few of them:

The Framingham Risk Score

One of the oldest tools to calculate cardiovascular risk is the Framingham Risk Score, which predicts a patient’s chances of having a heart attack or dying of heart disease in the next 10 years (another version is available that assesses your 30-year risk). The original Framingham calculation is made based on your age, gender, smoking status, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL, “good”) cholesterol, systolic blood pressure (the top number in the reading) and whether you’re being treated for high blood pressure.

Other risk factors have since been added to the Framingham system, and several risk calculators based on the Framingham system are now available at www.framinghamheartstudy.org/risk-functions/index.

The Framingham Risk Score categorizes patients as follows:

Low risk: Your odds of heart attack or cardiac death in the next 10 years are less than 10 percent.

Intermediate risk: Your odds of heart attack or cardiac death in the next 10 years are 10–20 percent.

High risk: Your odds of heart attack or cardiac death in the next 10 years are greater than 20 percent.

A slightly modified version of the Framingham Risk Score was used by the National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) to guide dyslipidemia screening and treatment recommendations (see Chapter 4 for more information).

The Reynolds Risk Score

Researchers have noted that among all cardiovascular events that occur in women, as many as 20 percent occur in women with none of the risk factors included in the Framingham Risk Score. So, they developed the Reynolds Risk Score, designed to better estimate 10-year cardiovascular risk in women (although a version for men is available, as well).

In a study of 24,558 healthy U.S. women followed for an average of about 10 years, the Reynolds score was more accurate than the ATP III risk score and helped to reclassify 40 to 50 percent of women that the ATP III system identified as intermediate risk into higher- or lower-risk categories (JAMA, Feb. 14, 2007).

The Reynolds system includes the same criteria found in the Framingham and ATP III systems, but adds the results of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (a measure of inflammation) and whether your mother or father suffered a heart attack before age 60 (a measure of genetic risk).

The 2013 ACC/AHA Risk Calculator

For many physicians, a global risk calculator based on guidelines released in 2013 by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) essentially replaced the older risk predictors. Available at tools.acc.org/ascvd-risk-estimator, the calculator takes into consideration age, gender, race (Caucasian or African-American), total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, blood pressure treatment, diabetes, and smoking status.

Like the Framingham score, the calculator gauges a person’s likelihood of developing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the next 10 years and, thus, his need for treatment with cholesterol-lowering statin drugs.

Older guidelines recommended medical therapy for patients with a 10-year cardiovascular risk of at least 20 percent. The 2013 guidelines, however, lowered the statin treatment threshold to people without cardiovascular disease who have a 10-year risk for a heart attack or stroke of 7.5 percent or higher. (See Chapter 4 for more about risk groups and treatment decisions.)

The guideline panel did not recommend routine use of other risk markers, including family history of premature cardiovascular disease, coronary artery calcium score, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and ankle-brachial index. However, the experts noted that these tests may be useful after using the ACC/AHA risk calculator when patients and physicians are unclear about treatment decisions.

The MESA Risk Score

One of the newest risk calculators is the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) risk score, published in 2015. It includes the traditional risk factors of age, gender, total and HDL cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, smoking status, and treatment for dyslipidemia or high blood pressure. However, the calculator also takes into account race (Caucasian, African-American, Chinese, and Hispanic), family history of heart attack, and results of coronary artery calcium scoring, an imaging study that detects and measures the extent of calcification in your coronary arteries. These calcium accumulations are a sign of atherosclerotic coronary heart disease.

Risk Calculations: Limitations and Benefits

Keep in mind that the results of any risk calculator are only estimates, and each calculator has limitations.

Some studies, for example, have found that the Framingham score may overestimate or underestimate cardiovascular risk among people over age 85, as well as African-Americans and certain other racial and ethnic populations. Other research suggests that the ACC/AHA estimator may overstate cardiovascular risk and increase the number of patients on statins, particularly those in the older population.

On the flip side, the calculator may underestimate risk and potentially delay or prevent statin treatment in higher-risk patients who are younger, critics contend. Years later, those younger patients may be candidates for statin treatment, according to the risk calculator, but would have missed out on the benefits of earlier statin treatment.

Regardless of the calculator used, experts suggest having your cardiac risk assessed periodically. (The ACC/AHA guidelines recommend that people ages 40 to 75 without clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or diabetes and an LDL level of 70 to 189 mg/dl have their 10-year risk recalculated every four to six years.)

These assessments can provide you with a heads-up about your increasing risks and your need to improve your cardiovascular health through lifestyle changes and, if necessary, medical treatment. Conversely, they also can reassure you and provide positive feedback that you’re doing the right things to bolster your heart health.

Understand that your cardiovascular health is a continuum, and that your risk will evolve constantly depending on how you manage your risk factors.

Women Are at Risk, Too

A common misconception among women is that cardiovascular disease is a man’s disease, and that breast cancer is a more significant concern. Fact is, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among both men and women and actually affects more women than men, according to the American Heart Association (AHA).

Additionally, cardiovascular disease is deadlier than all forms of cancer combined: Each year, cardiovascular disease is responsible for one of out of every three deaths among American women, compared with one out of 31 deaths for breast cancer, the AHA says. The overall death rates from cardiovascular disease have decreased among men and women; however, these reductions have been smaller for women, according to the American College of Cardiology, and the death rate in women under age 55 has risen.

Furthermore, research suggests that women’s awareness of cardiovascular disease is not where it should be, and that female patients and their physicians do not place enough emphasis on cardiovascular disease.

In a 2017 study, researchers surveyed 1,011 American women (ages 25 to 60), 200 primary care physicians, and 100 cardiologists to get an idea about their knowledge and beliefs about cardiovascular disease in women (Journal of the American College of Cardiology, June 2017). The findings showed that more than 70 percent of women never addressed heart health with their physician (see sidebar).

“Increasing awareness of cardiovascular disease in women has stalled, with no major progress in almost 10 years, and little progress has been made in the last decade in increasing physician awareness or use of evidence-based guidelines to care for female patients,” the study’s lead author, C. Noel Bairey Merz, MD, director of the Barbra Streisand Women’s Heart Center at the Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute, said in an ACC statement.

“These findings suggest a need to destigmatize cardiovascular disease for women and counteract stereotypes with increased objective risk factor evaluation education to improve treatment by physicians,” she continued. “National action campaigns should work to make cardiovascular disease ‘real’ to American women and destigmatize the disease by promoting the use of cardiovascular risk assessment to counter stereotypes with facts and valid assessments.”

The post 3. Know Your Cardiovascular Risk appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 3. Know Your Cardiovascular Risk »

Powered by WPeMatico