1. Your Healthy Heart and Brain

You’ve surely heard the phrases “brain food” and “heart-healthy diet.” While some foods do seem to have specific brain benefits, in general, scientists are discovering that a diet that supports a healthy brain is also heart-healthy fare and vice versa. Learning which foods your brain and heart need to function optimally and how to incorporate these foods into an everyday eating plan can help protect both of these vital organs. That’s the mission of this book: To provide you with strategies, exemplified in the Tufts 10-Day Heart-Brain Diet, that will lead to positive changes in your risk profiles for heart and brain disorders.

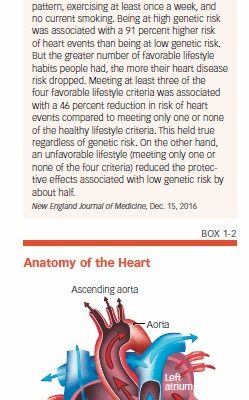

Even people with genetic risk factors for heart disease can benefit from these lifestyle changes (see Box 1-1, “Healthy Lifestyle May Offset Genetic Heart Risk”).

Your Demanding Brain

It makes sense that keeping your heart healthy is also good for your brain. After all, biologically speaking, that three-pound organ inside your skull is kept alive by the beating of an organ in your chest that itself weighs only 8 to 10 ounces. Your heart beats about 100,000 times a day, pumping 2,000 gallons of blood through more than 60,000 miles of blood vessels. Though this circulatory system has many functions, none is more important than keeping your brain supplied with energy and oxygen.

Moreover, the brain is quite demanding. Although an average brain makes up only about two percent of total body weight, it consumes 20 percent of the energy taken in from food and 20 percent of the oxygen breathed. Under ordinary circumstances, your brain uses 20 to 25 percent of the blood supply circulated by your heart. When your brain is hard at work, it requires an even greater blood supply.

The Role of Blood Vessels

The heart-brain connection begins with the blood vessels that provide your brain with nutrients and oxygen. Whatever is bad for your blood vessels is bad for your brain. The most obvious example is vascular dementia, the second most common form of dementia (Alzheimer’s disease is the most common). Vascular dementia is caused by a stroke or a series of tiny strokes that cut off or restrict the flow of blood to brain cells. Narrowing and stiffness of blood vessels can also accelerate cognitive decline, as well as the degree of impairment that occurs due to Alzheimer’s disease or a condition known as dementia with Lewy bodies (also called Lewy body dementia).

More evidence for the link between blood vessels and brain function comes from the Diabetes Heart Study-Mind. Researchers measured the amount of calcified plaque in participants’ coronary arteries, and then put participants through a battery of cognitive tests seven years later. The participants who had more plaque in their arteries had poorer cognitive function.

The Circulatory System

Before we delve into specific dietary patterns and foods that benefit your heart and brain, however, it’s important to understand how your circulatory system works to “feed” your body and brain. Your body is constantly circulating a little over five quarts of blood; to keep that blood moving, your heart will beat more than 2.5 billion times during an average lifetime.

About half of your blood is composed of a straw-colored fluid called plasma; the rest is made up of red blood cells, platelets, and white blood cells. Red blood cells transport oxygen using a substance called hemoglobin that binds to oxygen in your lungs. A single red blood cell contains 250 million hemoglobin molecules. Platelets cause your blood to form clots to stop bleeding, and white blood cells defend against infection.

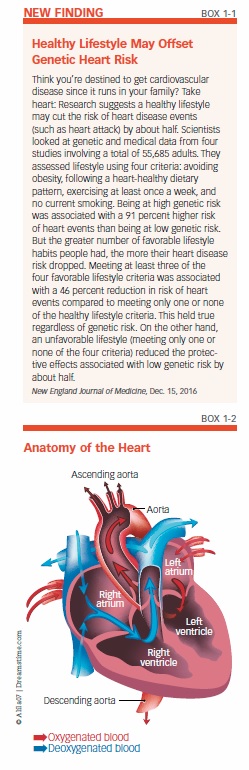

The circulatory system delivers oxygen-depleted blood to the right atrium, one of two upper chambers in the heart (see Box 1-2, “Anatomy of the Heart”). Blood then flows to the right ventricle, which pumps blood to the lungs to pick up a fresh load of oxygen. Oxygen-rich blood is then received by the left atrium and transferred to the left ventricle, which pushes it out through the aorta.

A Network of Blood Vessels

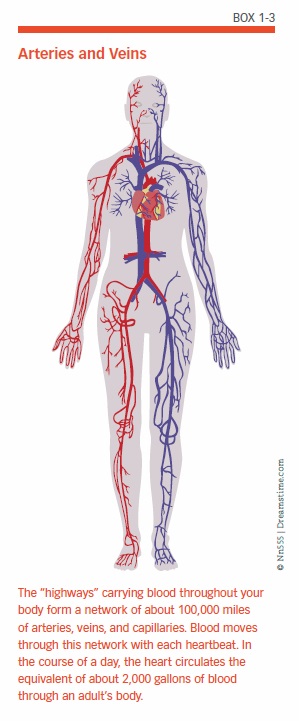

You might think of the body’s circulatory system as a network of three primary “highways” that serve the heart (coronary circulation), the lungs (pulmonary circulation), and the rest of the body, including the brain (systemic circulation). Carrying the blood through this network is a system of blood vessels called arteries, capillaries, and veins (see Box 1-3, “Arteries and Veins”). In this network, the arteries and veins are the main roads, and the capillaries are the side streets. In addition to supplying the body with oxygen, this system also transports nutrients and waste products.

Arteries such as the aorta, which is the largest artery, carry oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the rest of the body. As the arteries branch off farther away from the heart, they get smaller. Arteries have thick walls because they carry large amounts of blood under a high amount of pressure from the heart. Muscles in these walls continually squeeze to keep the blood moving smoothly. The arteries are lined with an inside layer, the endothelium, that provides a smooth surface over which the blood can easily flow.

Once the body’s tissues and organs have received oxygen and nutrients from the bloodstream, veins bring the depleted blood back to the heart. The largest vein in your body is the inferior vena cava, which returns blood from the lower half of your body to your heart.

Capillaries are the tiny bloods vessels that reach the body’s tissues and organs. These blood vessels have thin walls that enable oxygen, nutrients, and carbon dioxide to pass easily to and from the body’s cells.

From Heart to Brain

The circulatory system sends blood to all of the body’s organs, including the brain. This vascular pathway transports blood to the brain through the carotid and vertebral arteries.

The carotid arteries, located on either side of the neck, and the vertebral arteries, which extend alongside the spinal column in the back of the neck, are responsible for delivering life-sustaining oxygen and nutrients to the brain.

Unlike other parts of the systemic circulatory network, in which nutrients, oxygen, and waste products can move freely in and out of the capillaries, the brain is protected by a special checkpoint called the blood-brain barrier. This barrier is a semi-permeable system that allows only certain substances to pass into the brain. The barrier protects the brain against viruses, toxins, and other substances in the blood that might harm the brain’s delicate tissues.

Network Problems

Damage or disease in the circulatory system can impede blood flow. Common problems with the circulatory system include:

Arrhythmia

An irregular heart rhythm is called an arrhythmia. When the electrical impulses inside the heart that control the heartbeat get out of rhythm, the heart can beat erratically, too quickly, or too slowly. A severe arrhythmia can impair the heart’s ability to pump enough blood throughout the body.

Atherosclerosis

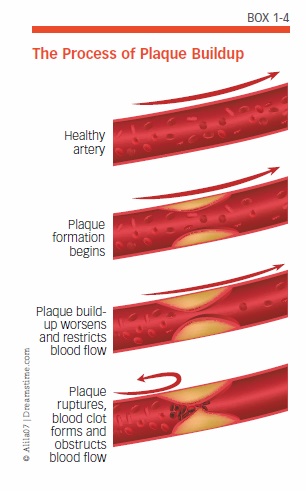

Atherosclerosis—often referred to as “hardening of the arteries”—occurs when plaque deposits made up of fat, cholesterol, and other substances build up on artery walls (see Box 1-4, “The Process of Plaque Buildup”). Over time, plaque buildup stiffens arteries and can narrow or completely block arteries. These narrowed arteries can develop clots that block blood flow, and bits of plaque can break off and block smaller arteries. Such blockages are a common cause of stroke and heart attack.

Atrial Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation, or “AFib,” is an irregular heartbeat that occurs in the two upper chambers, the atria, of the heart. AFib is especially relevant to brain health because it can cause blood to stagnate and form a clot that can travel to the brain, blocking a blood vessel and causing a stroke. Having AFib can raise your stroke risk by as much as 500 percent.

Carotid Artery Disease

Carotid artery disease is caused by the buildup of plaque in the blood vessels that feed the front part of the brain. If the blood flow in a carotid artery is blocked, it can damage or destroy brain cells. Carotid artery disease can lead to a stroke or a transient ischemic attack (TIA), also called a “mini-stroke.”

Coronary Artery Disease

Plaque can also accumulate in the arteries that supply blood, oxygen, and nutrients to the heart—a condition called coronary artery disease (or coronary heart disease). When plaque builds up on walls of the coronary arteries, the artery narrows and decreases the blood flow to the heart. If the artery becomes completely blocked, a heart attack may occur. Plaque buildup can also lead to the formation of clots; if a clot breaks free and blocks a blood vessel in the heart, it can cause a heart attack. Coronary artery disease is the most common heart condition in adults.

Stroke

The most common type of stroke, an ischemic stroke, occurs as a result of an obstruction within an artery that supplies blood to the brain. Ischemic strokes account for about 87 percent of all strokes. The obstructions can take two forms:

- A blood clot (thrombus) that develops at the clogged part of a carotid artery is a cerebral thrombosis.

- A blood clot that forms elsewhere in the circulatory system, most often in the heart or the large arteries of the upper chest and neck, breaks loose into the bloodstream and travels into the brain until it reaches and blocks a smaller blood vessel; this is called a cerebral embolism.

The second major type of stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, results from weakened blood vessels in the brain that rupture and bleed. The accumulated blood can damage the surrounding brain tissue.

In addition to the brain damage that may be caused by a stroke, research also suggests that stroke victims are at greater risk of impaired cognitive function. One study found that stroke survivors experienced a 23 percent relative acceleration in cognitive impairment compared to people without strokes.

Focus on Risk Factors

Many health conditions that increase your risk of cardiovascular disease can also put your brain’s health in jeopardy. In the following pages, you will find explanations of the most common risk factors for cardiovascular disease, as well as the dietary strategies that can reduce your risks.

Obesity

Excess body weight is a key contributor to cardiovascular disease, as well as other heart disease/dementia risk factors, including diabetes, inflammation, and high blood pressure. More than 37 percent of American adults are obese, and more than two-thirds of American adults are overweight.

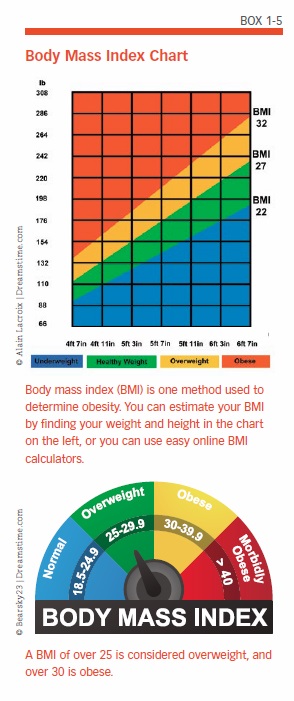

Research suggests that individuals who are overweight or obese at age 50 are at a greater risk for decreased cognitive function and dementia as they age. In a long-running study on human aging, researchers found that being overweight or obese, measured by body mass index (BMI), at age 50 was associated with earlier onset of Alzheimer’s in those who developed the disease. (See Box 1-5, “Body Mass Index Chart,” to find out if you are overweight or obese based on your BMI.)

Extra weight can also compound the cognitive effects of other chronic health conditions. In one study, having a lower body mass index was associated with better cognition at the study’s start. Over time, participants who were both obese and suffering from conditions such as diabetes or high cholesterol more often experienced a faster rate of cognitive decline.

Although any excess weight is unhealthy, “belly fat” is especially dangerous. A growing waistline can have a detrimental effect on both your heart and brain. Fat in your abdominal cavity, which is also called visceral fat, isn’t the same as the subcutaneous fat that lies just beneath your skin. Visceral fat is located in the spaces between the internal organs, such as the stomach, liver, and intestines. Researchers have discovered that visceral fat cells release a number of damaging substances that play a role in the development of heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease.

Losing weight also may be an important tool for protecting your brain. Cutting calories and losing weight might help older people sharpen their mental skills, according to a study that found that obese people who lost weight had improved scores on cognitive tests of thinking, verbal memory, executive function, and language.

Calorie Cautions

While the relationship between weight, metabolism, and diet is complex, it remains generally true that if you consume more calories than you burn, you’ll gain weight. Calories are the fuel your body, heart, and brain need to function, and they are an important nutrient in themselves. But most Americans overdo calorie intake, which isn’t all that surprising given the amount of highly processed, prepared convenience foods that are available. Since obesity is a risk factor for a number of conditions, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes, that increase the likelihood of developing heart disease, that means more than one-third of the adults in the U.S. have a higher risk of heart disease solely because they are obese.

Studies have also shown that both overweight and obese adults are at higher risk of dementia than those who are of normal weight. Obesity has even been linked with smaller brain volume.

By choosing nutrient-dense foods, you can maximize your nutritional benefits in the tradeoff between calories and other nutrients. Making smart choices can help you maintain a healthy weight while protecting your heart and brain.

Prehypertension and Hypertension

It’s never too early to start keeping an eye on your blood pressure. If your blood pressure readings are consistently ranging from 120 to 139 in the top number (the systolic pressure) and/or 80 to 89 in the bottom number (the diastolic pressure), you already have a condition called prehypertension. Unless you take steps to control your blood pressure—such as the lifestyle measures discussed in this publication—you are at risk of developing high blood pressure, or hypertension. Hypertension, which is defined as a blood pressure reading of 140/90 or above, puts you at greater risk for heart attack, angina, kidney failure, peripheral artery disease, and stroke.

Hypertension is also bad for your brain. High blood pressure in midlife is associated with a greater risk of dementia, which may be due to mini-strokes, strokes, damage to the blood vessels, or too little blood and oxygen being delivered to the brain. When the functions of the blood vessels in the brain (called cerebral blood vessels) are compromised by high blood pressure and other conditions, the activity of neurons in the brain—the cells that transmit information—may be disrupted and can impair brain function.

Hypertension’s Effects

High blood pressure makes the heart have to work harder and puts more strain on the arteries. Over time, high blood pressure weakens the artery walls, and it can eventually damage the muscles and valves of the heart itself, which can cause heart failure, a condition in which the heart is unable to pump an adequate amount of blood.

When artery walls become weak, they are more vulnerable to damage, such as rupture and scarring; damaged areas provide an ideal environment for plaque to accumulate, which can lead to or worsen coronary artery disease. This type of damage can affect the brain as well. In fact, high blood pressure is a leading cause of stroke.

Research has also shown that high blood pressure is associated with greater damage to the brain’s white matter, which insulates and protects the neural circuits.

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

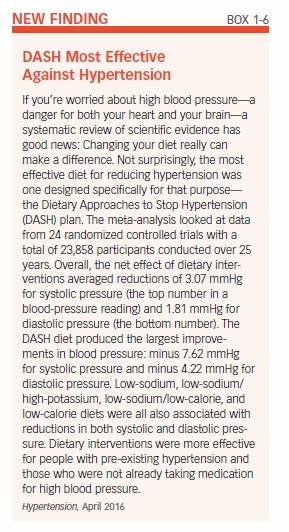

Controlling blood pressure is important for cardiovascular health as well as for protecting your brain against strokes and dementia. If you have prehypertension or already suffer from hypertension, you can benefit from adhering to the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) eating plan (see Box 1-6, “DASH Most Effective Against Hypertension”). The DASH plan was designed by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute based on clinical studies that tested the effects of sodium and other nutrients on blood pressure.

A Healthy Way to Eat

DASH is a healthy way to eat, regardless of whether or not you have prehypertension or high blood pressure. In addition to lowering both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, the DASH approach lowers unhealthy LDL cholesterol and may offer protection against cancer, cognitive decline, and diabetes, as well as helping with weight control.

The DASH dietary pattern also supports a studies that examined the DASH-style diet in relation to heart health, researchers linked this pattern to a 20 percent reduction in cardiovascular disease, a 21 percent reduction of coronary heart disease, a 19 percent reduction in stroke, and a 29 percent reduction in heart failure.

The DASH diet is high in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy. It emphasizes whole grains, fish, poultry, and nuts and limits red meats, added sugars, and sodium. Overall, the plan is rich in phytonutrients, potassium, magnesium, calcium, and fiber.

As we will see, there are many similarities between DASH and a Mediterranean-style diet. Although both dietary patterns offer clear health benefits, there is one important difference: the amount of fat consumed. A Mediterranean-style diet is generous with unsaturated fats, whereas DASH limits fats from all sources. Our 10-Day Heart-Brain Diet favors the former approach to fats, in recognition of research and dietary guidelines updates since the original DASH research was conducted.

Cholesterol in Your Blood

Your body, primarily your liver, makes cholesterol, a waxy substance that circulates through your blood. Your body requires some cholesterol, since it is needed for the production of cell membranes, vitamin D, hormones, and bile acids. Saturated fat and trans fat in foods such as meat, baked goods, and processed foods cause your liver to produce more cholesterol. Genetics also plays a role in how much cholesterol your body makes.

Health problems can occur when you have too much cholesterol in your blood vessels (this is “serum” cholesterol, as opposed to dietary cholesterol, which is the cholesterol in the foods and beverages you consume). Excess serum cholesterol can contribute to the formation of plaque between layers of artery walls, which causes atherosclerosis and makes it harder for your heart to circulate blood. Researchers have observed that plaques in the carotid arteries and thickening of blood vessel walls are associated with both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Other research has associated abnormal cholesterol levels in midlife with an increased risk of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease.

Not all serum cholesterol is harmful. The low-density lipoprotein (LDL) form of cholesterol is the type associated with arterial plaque buildup (for more on this topic, see Chapter 2). Conversely, beneficial high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol carries LDL cholesterol away from the arteries and back to the liver, where it is broken down into waste products and eliminated from the body. HDL cholesterol also might help preserve memory by reducing the formation of beta-amyloid, a substance that clusters to form plaques in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

It’s important to distinguish between serum cholesterol and the dietary cholesterol found in foods such as eggs. The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans made headlines by dropping its recommendation for a specific limit on dietary cholesterol. This change occurred because experts determined that dietary cholesterol is not a key contributor to the serum cholesterol in your blood vessels.

Diabetes and Insulin Resistance

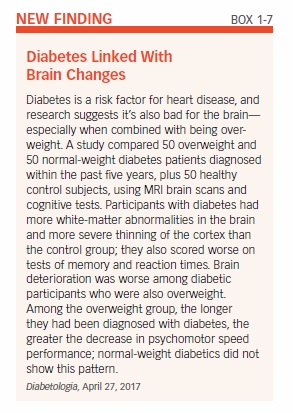

Diabetes has serious consequences not only because of the toll of the disease itself, but also because diabetes raises cardiovascular risk. Moreover, increasing evidence suggests that the unhealthy blood sugar levels associated with diabetes contribute to cognitive decline (see Box 1-7, “Diabetes Linked With Brain Changes”).

When you consume carbohydrates, your digestive system breaks down their component sugars and starches into a simple sugar called glucose. Insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas, acts like a “key” to unlock the body’s cells so glucose can pass from the blood into the cells and be used as energy or stored as fat. In the condition called insulin resistance, the cell receptors that respond to insulin no longer work as well—no matter how much insulin the pancreas produces, glucose can’t exit from the bloodstream, and levels go up.

Insulin resistance is the single best predictor of type 2 diabetes risk, and it also increases the risk of heart disease. Maintaining a healthy weight and being physically active are the most effective ways to prevent insulin resistance. Most people who are overweight are also insulin resistant, although a small number of lean people also develop insulin resistance, likely for genetic reasons.

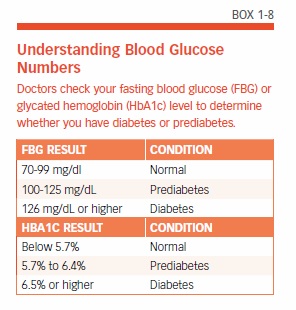

When blood glucose levels remain high over time, the pancreas cannot produce enough insulin to handle the excess glucose; consequently, blood glucose levels remain elevated, and a patient may be diagnosed with prediabetes. Finally, the condition may progress to type 2 diabetes (see Box 1-8, “Understanding Blood Glucose Numbers”).

Diabetes and the Brain

Chronically high blood glucose levels also seem to affect the brain. A study of more than 350,000 people over nearly five years reported that people with very high blood glucose levels were at 23 percent greater risk of dementia than those with lower levels.

People whose blood glucose is higher than normal but not high enough to meet the criteria for diabetes are also at greater risk: The same study found that people with elevated blood glucose levels that were not high enough for a diagnosis of diabetes were 20 percent more likely to develop dementia than those with normal blood glucose levels.

Insulin resistance may also be tied to cognitive decline, at least in women: A study reported that higher levels of insulin resistance were associated with poorer verbal fluency in women but not men. Researchers said the findings suggest that insulin resistance may be an early marker of cognitive decline and perhaps even a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease in women.

Your Brain on Sugar

Why do problems with blood glucose and insulin affect the brain? High blood glucose prevents the blood vessels from opening (dilating) wide enough to let blood flow through easily. This contributes to increased plaque buildup, heart disease, and impaired blood flow to the brain, as well as all other organs and tissues. Excess glucose also might damage brain function by altering components of neurons, increasing oxidative stress, and producing inflammation.

Insulin resistance also may lead to high blood pressure because of the action of insulin on the kidneys; excess insulin may cause the kidneys to retain more sodium (salt), which increases the fluid volume in the arteries, resulting in elevated blood pressure.

An enzyme that is involved in regulating insulin may also play a role in brain health. The enzyme that breaks down insulin also works to break down beta-amyloid, a compound that accumulates in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Scientists speculate that when the enzyme is occupied attacking excess insulin, beta-amyloid may be left to build up in damaging plaques.

Choices for Heart-Brain Health

Your cardiovascular fitness and blood pressure in midlife might help predict your brain health decades later (see Box 1-9, “Midlife Heart Risk Factors Boost Brain Amyloid”).

Even if you are age 60 or older, though, it’s not too late to make changes now that can benefit your heart and brain as you age. For example, one study assessed whether lifestyle changes had an effect on the cognitive function of adults ages 60 to 77. Half of the study participants were randomly assigned to an intervention including dietary changes, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring, while the other half, the control group, was merely given general health advice. After two years, researchers administered comprehensive neurological tests to all participants. The intervention group had a 25 percent higher improvement in total scores of cognitive function than the control group.

The Cost of Unhealthy Behaviors

On the other hand, unhealthy behaviors, including smoking, inactivity, and poor diet, are clearly linked to long-term brain health. In one study, for example, people who engaged in unhealthy behaviors (smoking, low fruit and vegetable consumption, low amount of physical activity, and high alcohol consumption) were nearly three times more likely to suffer impairments in thinking and twice as likely to have memory problems as those with the healthiest lifestyles. Participants with three or four unhealthy behaviors were 84 percent more likely than participants with zero unhealthy behaviors to have poor cognitive function 17 years later.

It’s up to you to align your lifestyle with healthy choices that can reduce your risk of cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline. That starts with how you feed your heart and brain—as we’ll see in the next chapter.

The post 1. Your Healthy Heart and Brain appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 1. Your Healthy Heart and Brain »

Powered by WPeMatico