4. Treating COPD

Even though COPD cannot be cured, it can be treated. Treatment is aimed at reducing symptoms, preventing the disease from getting worse, improving the ability to exercise, preventing and treating complications, and preventing and treating exacerbations.

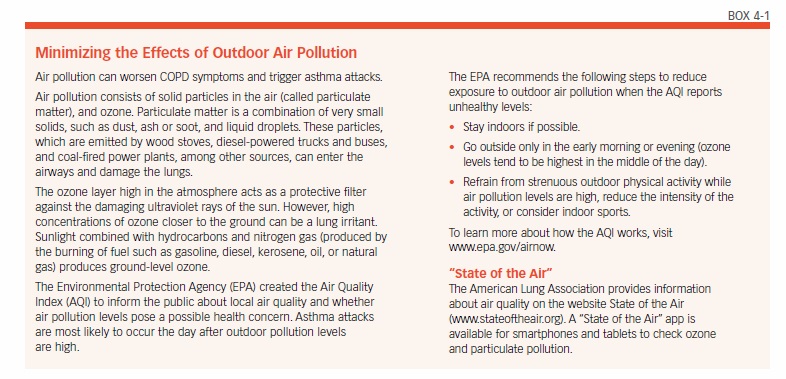

For those with COPD who are current smokers, the most important first step is to quit. Smoking cessation helps to slow down the disease, especially in its early stages. People with COPD should also reduce their exposure to secondhand smoke, occupational sources of lung irritants (like dust and chemicals), and indoor and outdoor air pollutants. When outdoor air quality is poor, persons with significant COPD should stay indoors to help reduce symptoms (see Box 4-1, “Minimizing the Effects of Outdoor Air Pollution”).

In people with COPD, the parts of the lungs damaged due to emphysema cannot be restored. Therefore, treatment is used to improve function in the parts of the lungs that are still working, and reduce inflammation in the lungs.

In addition to medications, regular physical activity is important for maintaining lung function. For patients with more severe disease, a specialized exercise program called pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to improve the ability to exercise and engage in basic daily activities with less shortness of breath. In severe disease, oxygen therapy is often required. Some people with advanced COPD may be candidates for lung volume reduction surgery, which may relieve symptoms and can improve quality of life, or lung transplantation. Everyone with COPD should receive immunizations for influenza and pneumonia.

Drugs to Treat Obstructive Airway Diseases

Drug therapy is part of the treatment for just about everyone with COPD or asthma. Drug regimens generally include two types of medicines:

- Bronchodilators to open narrowed airways

- Anti-inflammatory drugs (corticosteroids) to reduce inflammation in the lungs.

Various combinations of these medications often are used.

Bronchodilators

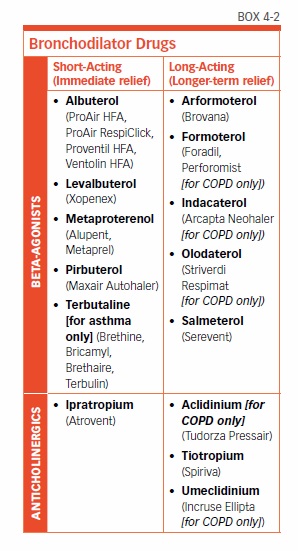

Bronchodilators expand the airways, making it easier to breathe and go about daily life. There are two main types of bronchodilators (see Box 4-2, “Bronchodilator Drugs”): beta-agonists and anticholinergics. Each is available in a short-acting and a long-acting formulation. A third type of bronchodilator, theophylline, is an older drug that is used less frequently.

Beta-agonists and anticholinergics can be taken orally, intravenously, or through inhalation. The preferred method for delivering the drugs to people with obstructive airway disease is inhalation. Using an inhaler device, the drug is breathed in and quickly goes to the airway, where it is needed. There are generally fewer side effects with inhaled medications than there are with pills.

To ensure that the correct amount of drug is delivered, proper inhaler technique is needed. Poor technique can result in too little drug reaching the lungs, as well as more side effects due to the drug being deposited in the mouth or the back of the throat.

Beta-Agonists

Beta-agonists activate a receptor on muscles surrounding the bronchial tubes, causing them to relax and allowing the airway to dilate. Short-acting beta-agonists start to work within minutes and last about four to six hours. Long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) take longer to begin working (about 20 minutes), but last up to 24 hours.

The possible side effects of beta-agonists include headaches, nervousness, dizziness, and shakiness. If side effects occur, they often last only a short time and diminish or resolve completely once the medication is used regularly. If they persist, a different medication, or a lower dose may be prescribed.

Anticholinergics

Anticholinergics block a receptor in the lung to prevent the airways from constricting. This allows the airways to remain open. The short-acting anticholinergic drug ipratropium (Atrovent) starts to work within 15 minutes, and lasts for six to eight hours. Long-acting anticholinergic drugs take 10-20 minutes to start working, and last 12-24 hours.

Possible side effects of ipratropium are coughing, headaches, nausea, heartburn, diarrhea, urinary retention, and constipation, among others. However, they are generally not serious and diminish or go away completely if the medication is stopped. If any side effect is severe, or does not go away, a different medication may be needed.

Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Anti-inflammatory medications reduce inflammation. Corticosteroids are the most commonly used anti-inflammatory drugs given to people with COPD or asthma to reduce swelling in the bronchial tubes. They can be taken in tablet, liquid, injected, or inhaled form.

Corticosteroids do not work as quickly as bronchodilators: It can take up to a week to notice the effect. The pill form acts faster than the inhaled version, but often causes more side effects.

Corticosteroids

Oral corticosteroids—most commonly prednisone (Deltasone) and predisolone (Medrol)—are generally reserved for treating acute exacerbations of COPD or asthma. Breathing becomes easier, coughing and wheezing subside, and mucus production lessens.

Even though oral corticosteroids have pronounced effects, they are generally only used for a short period of time (a few days to a few weeks). This is because in addition to reducing inflammation, corticosteroids have other effects on the body that can cause unwanted and potentially severe consequences. Taken by mouth in moderate-to-high doses for months or years, corticosteroids can cause bruising of the skin, cataracts, bone thinning (osteoporosis), muscle weakness, hair loss, growth of facial hair in women, mood changes, and weight gain. Anyone who uses oral steroids for long periods of time may also be susceptible to developing high blood pressure and/or diabetes. Moreover, when oral steroids are used for more than a few weeks, the body becomes accustomed to the drug and it cannot be stopped abruptly without adverse effects. Therefore, anyone who takes an oral steroid for several weeks or more must taper off the drug rather than stopping it abruptly.

Inhaled Corticosteroids

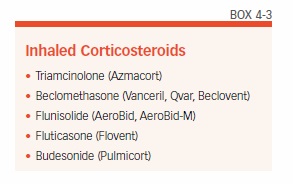

Most people with obstructive airway disease who take corticosteroids will use the inhaled form (see Box 4-3, “Inhaled Corticosteroids”). By using an inhaler device, the medication is delivered directly to the lungs. Very little medication travels through the bloodstream, which minimizes side effects. In commonly used doses, inhaled steroids are safe to use over the long term. Possible side effects are a sore throat, hoarse voice, and a yeast infection in the mouth (oral candidiasis). Candidiasis can be avoided by rinsing your mouth with water after each use of the inhaler, or by using a spacer.

As with bronchodilators, proper technique using the inhaler device is critical to the successful delivery of the correct dose of the drug.

Types of Inhalers

Inhalers deliver bronchodilators or corticosteroid medications as a spray, mist, or fine powder. Three types of devices are available to deliver inhaled medications: a metered dose inhaler (MDI), a dry powder inhaler (DPI), and a nebulizer.

Metered Dose Inhalers

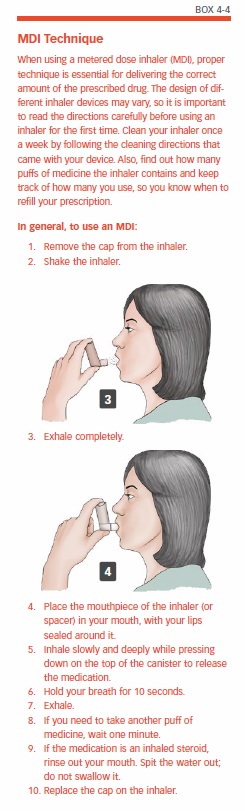

An MDI is a small, pressurized canister with a mouthpiece and a metering valve that contains medication. The patient places his or her mouth over the mouthpiece, and then inhales while pushing down on the top of the canister to deliver a precise dose of the medication.

The proper technique for using an MDI inhaler is described in Box 4-4, “MDI Technique.” Several common mistakes can lead to too little or too much medication being delivered. For example, some people exhale before the end of the spray, or inhale after the medication is sprayed. Other mistakes include inhaling through the nose instead of the mouth, squeezing the canister twice but only inhaling once, or forgetting to take the cap off the mouthpiece.

Many people find it helpful to use a spacer device with their MDI to improve drug delivery. A spacer is a short tube that is placed between the mouthpiece of the inhaler and your mouth. The medicine enters the tube, and from there it can be inhaled more slowly and deeply. This results in more effective delivery of the medicine to the lungs.

The medication in the MDI canister is suspended in a mixture of substances. One of these is a propellant, which squirts the mixture out of the device and gives it enough momentum to get down into the lungs. The mix also contains preservatives, flavoring agents, and chemicals that help to disperse the drug throughout the lung.

Each inhaler has different directions for washing, drying the mouthpiece, and priming. It’s important to follow the instructions that come with the inhaler your doctor has prescribed.

Dry Powder Inhalers

DPIs are similar to MDIs, but they don’t contain a propellant. Using a DPI requires inhaling more deeply and quickly to suck the medicine out of the device and into the lungs. DPIs are easy to use, as they don’t require the coordination of taking a breath while actuating the device with your hand.

To use a DPI, simply place your mouth tightly over the mouthpiece and inhale quickly. A DPI inhaler should not be shaken before use (like an MDI), nor is a spacer needed.

Nebulizers

Inhaled medications like bronchodilators and corticosteroids can also be delivered via a nebulizer. A nebulizer is a machine that turns the liquid form of a drug into a fine mist that is then inhaled through a mouthpiece or facemask. Nebulizers are often used for treating very young children who have asthma. They are also used for older children and adults who have more severe lung disease, or who have difficulty using MDIs or dry powder inhalers.

The long-acting bronchodilator formoterol is available for use in a nebulizer. This drug is an alternative to MDI and DPI inhalers for COPD patients who may have difficulty using inhaler devices easily or correctly.

Treatment Options for COPD

Almost every person with COPD will be prescribed a short-acting bronchodilator (either a beta-agonist, an anticholinergic, or a combination of both) to use as needed to relieve shortness of breath, coughing, wheezing, and other symptoms. Some people will also need a long-acting bronchodilator and/or an anti-inflammatory drug. Your doctor will work with you to figure out the right drugs and combinations of drugs to relieve your symptoms.

For a person with mild COPD who has occasional symptoms, a short-acting bronchodilator alone may be sufficient to manage the condition. Two short-acting bronchodilators—a beta-agonist plus an anticholinergic—may also be prescribed. To simplify this regimen, a combination of a short-acting beta-agonist plus a short-acting anticholinergic is available in one inhaler (see Box 4-5, “Combination Drugs”). This may be the combination of albuterol plus ipratropium (Combivent Respimat, DuoNeb) or fenoterol plus ipratropium (Duovent).

As lung function deteriorates, additional medications will likely be necessary.

For people with moderate or severe COPD, who tend to experience symptoms more frequently, one or more long-acting bronchodilators will be added to the regimen. These drugs will be taken regularly every 12 or 24 hours. If acute episodes of breathlessness or coughing occur while taking these medications, a short-acting bronchodilator such as albuterol (Ventolin, Proventil, ProAir, VoSpire ER) can be used to quell the episodes.

For patients with more severe COPD, combinations of two long-acting bronchodilators are generally used. Combinations of two long-acting bronchodilators in a single inhaler are available.

Inhaled corticosteroids are recommended for people with moderate or severe COPD who do not get sufficient relief from bronchodilators, or who experience frequent exacerbations of symptoms. Inhaled corticosteroids have been shown to reduce flare-ups.

Some studies have found that use of inhaled corticosteroids, with or without a bronchodilator, increases the risk of developing pneumonia. Nevertheless, inhaled corticosteroids may decrease the risk of dying from pneumonia. Further research is needed to clarify these issues, and patients should discuss any concerns with their physician.

For people prescribed long-term use of both a long-acting bronchodilator and a corticosteroid, combinations of both in a single inhaler are available.

Roflumilast

Roflumilast (Daliresp) is a different type of drug for COPD. A PDE4 inhibitor, it works through a different mechanism than bronchodilators and anti-inflammatory drugs. Roflumilast is taken once a day to reduce inflammation in the lungs. It is not a bronchodilator.

Expectorants and Cough Suppressants

People with COPD often use expectorants, which can be obtained in cough medicines such as guaifenesin (Robitussin, Mucinex), to thin mucus and help to bring it up. However, there is little evidence to show that these medicines are helpful for people with COPD.

Cough suppressants should be avoided. Even though coughing can be bothersome, it has the important function of helping to clear mucus. This means that suppressing a cough may increase the risk of lung infection.

Immunizations

For people with obstructive airway diseases, the flu can be very serious and even life threatening. The same applies to pneumonia, although this can be treated with antibiotics. Fortunately, vaccines are available to protect against influenza and some forms of pneumonia. It is extremely important that everyone with obstructive airway disease follow the recommended vaccination schedule, or their doctor’s advice.

Flu Vaccine

People with COPD or other lung problems should receive an influenza vaccination once a year. The ideal time to get a flu shot is in October or November, as flu season runs from November to March.

Pneumococcal Vaccine

The pneumococcal vaccine protects against the bacteria that is the most common cause of pneumonia, Streptococcus pneumoniae. There are now two forms of pneumococcal vaccine, the Pneumovax and the Prevnar 13. It is recommended that all adults over age 65 receive a pneumococcal vaccination. Unlike the flu shot, which must be given every year in the fall, pneumococcal vaccination provides protection for at least five years. It can be given at any time of the year.

The pneumococcal vaccine is advised for all people with COPD age 65 and older. It also may be given to people with COPD who are younger than age 65 and have severe or very severe disease (FEV1 less than 40 percent of predicted), and recommended for people with asthma who are younger than age 65.

Treatment for Exacerbations

The most common cause of an exacerbation is a lung infection that may increase mucus production. In these cases, antibiotics may be used. Before prescribing an antibiotic, the doctor may send a sample of the sputum for analysis to determine whether the infection is bacterial or viral, since antibiotics are only effective against bacteria. Studies have shown that a short course (five days) of antibiotics is just as effective as taking antibiotics for longer than five days.

In 2017, the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society issued joined guidelines on the management of COPD exacerbations. Their recommendations included:

- For ambulatory patients with an exacerbation of COPD, a short course of oral corticosteroids plus antibiotics.

- For patients hospitalized with an exacerbation, oral corticosteroids rather than intravenous corticosteroids, if possible.

- For patients hospitalized with an exacerbation causing respiratory failure, noninvasive mechanical ventilation.

- After being discharged for an exacerbation, pulmonary rehabilitation should begin within three weeks. It should not be started during hospitalization.

A recent study found that engaging in any amount of regular exercise following hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation actually reduces the risk of dying.

Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Therapy

Younger adults who inherited alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency may be treated with alpha-1 antitrypsin augmentation therapy. This involves using a concentrated form of this protein that has been removed from donated blood and purified.

Augmentation therapy cannot reverse damage that has already been done to the lungs, but it can slow down any further decline in lung function. The therapy must be taken for life, and is very expensive. It must be administered by a healthcare professional in a doctor’s office, hospital clinic, or home infusion service. The costs may be covered by private health insurance policies, but criteria for coverage can vary widely. Before beginning therapy, check with your insurance company. For people age 65 and older, Medicare covers at least part of the cost.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

A very helpful addition to drug therapy for people at all stages of COPD is a specialized program called pulmonary rehabilitation. Pulmonary rehabilitation is a series of educational and structured exercises that enable people to make the most of their remaining lung capacity. People with COPD who engage in these programs have less shortness of breath, an increased ability to exercise, better quality of life, and less frequent hospitalizations than similar COPD patients who do not participate in pulmonary rehabilitation.

People with COPD tend to slow down their physical activity, since shortness of breath makes exertion increasingly difficult. Decreasing activity can start a vicious cycle of progressive deconditioning, and this leads to worsening of symptoms, more breathlessness, and less physical activity. Pulmonary rehabilitation is aimed at breaking that cycle.

A pulmonary rehabilitation program is more than an exercise program, although exercise is the most important component. In addition to exercise training, the program may include:

- Nutrition counseling

- Education about your condition

- Breathing strategies

- Energy-conserving techniques

- Help with smoking cessation

- Education about medications and how to take them

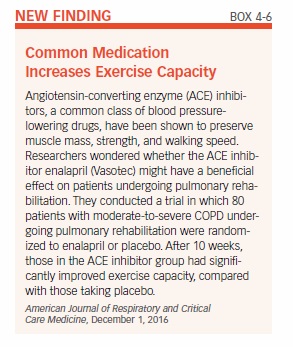

One study found that including music therapy in a pulmonary rehabilitation program provided added benefit. The participants, who attended six-week pulmonary rehab programs, also took part in weekly music therapy sessions that included playing wind instruments, and singing. They demonstrated greater improvements in symptoms such as shortness of breath, fatigue, and depression compared with COPD patients who had standard pulmonary rehab. Another study found that adding angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) might improve response to exercise training (see Box 4-6, “Common Medication Increases Exercise Capacity”).

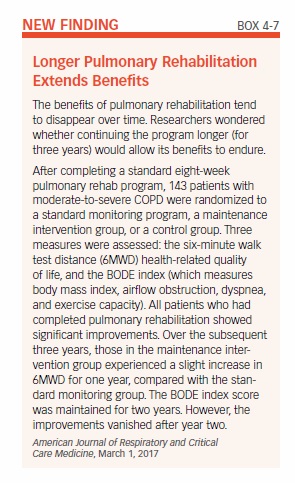

Most pulmonary rehabilitation programs last six weeks or longer. The exercises learned during the program should be continued at home once the program ends. Studies have found that pulmonary rehabilitation benefits are generally sustained after the program ends, especially if the exercise training is maintained (see Box 4-7, “Longer Pulmonary Rehabilitation Extends Benefits”).

One study found that people in the earlier derived greater benefits than those in the later stages. Although patients with less-advanced COPD had better results, those with severe COPD had improved ability to exercise and less shortness of breath. This research suggests that when it comes to pulmonary rehabilitation, the earlier it is done the better. However, patients with any stage of COPD can benefit from the program.

There are many pulmonary rehabilitation programs around the country. Your physician can most likely refer you to one; alternately, contact the American Lung Association or the American Association for Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, which has a searchable online directory of pulmonary rehabilitation programs (see Appendix II: Resources). Be sure to ask your insurance carrier whether it covers pulmonary rehabilitation. Medicare coverage varies from state to state, so check with your physician or pulmonary rehabilitation provider to obtain the guidelines in your state.

Oxygen Therapy

People with severe COPD may have low levels of oxygen in their blood (a condition called hypoxemia). This may cause increased difficulty breathing, and further impair the ability to exercise. Low oxygen levels may also cause fatigue, memory loss, morning headaches, depression, and confusion. Over time, chronically low oxygen levels also can cause heart failure. Oxygen therapy can ensure the delivery of adequate oxygen to preserve the function of vital organs.

Many people with COPD have few, if any, symptoms that can be specifically linked to hypoxemia. To determine whether someone has hypoxemia, a physician will perform either an arterial blood gas test or pulse oximetry. In pulse oximetry, a noninvasive probe is attached to the finger, ear, or forehead to measure the amount of oxygen in the blood. The test may be done both at rest and while walking, since the oxygen level in the blood is often only low during activity.

Oxygen therapy usually is given only to people with very severe (stage IV) COPD (see Box 3-1, “Stages of COPD,” in Chapter 3). In stage IV COPD, airflow is severely limited, and the amount of air that can be blown out in one second (FEV1) is less than 30 percent of what would be expected in someone without lung disease. For these people, long-term use of supplemental oxygen for more than 15 hours each day can prolong life and improve quality of life. Oxygen therapy can reduce shortness of breath during exertion, which makes it easier to perform basic daily activities. Oxygen therapy also may improve mental functioning, reduce depression, and help the heart.

The normal air we breathe contains about 21 percent oxygen. Providing more pure oxygen can increase the amount of oxygen taken into the lungs. The physician will prescribe a specific amount of supplemental oxygen, and provide instructions on when and how long it should be used, as well as which delivery method will be used. Supplemental oxygen may be used continuously (24 hours) or periodically, such as only during exercise or overnight. There are three methods for delivering oxygen, as explained below. With each system, the oxygen is breathed in through a mask or a nasal tube (cannula).

Compressed Oxygen Gas

Compressed oxygen gas is contained in tanks or cylinders of varying sizes. Large stationary tanks are used inside the home, while smaller, more portable tanks can be used on trips outside the home (they usually contain enough oxygen to last a few hours).

Liquid Oxygen

Cooling oxygen gas creates a liquid form of oxygen. When the liquid is warmed, it turns back into a gas that can be inhaled. Like compressed oxygen gas, liquid oxygen systems include a large tank for use in the home, and a small portable canister for use outside the home. This canister is filled with liquid oxygen from the indoor tank. One disadvantage of liquid oxygen systems is the tendency for the liquid to evaporate over time.

Oxygen Concentrator

An oxygen concentrator is an electric device that takes air from the room and separates the oxygen from other gases. The oxygen is then made available for inhaling through a mask or nasal cannula. This system does not require tanks of liquid or gaseous oxygen to be continuously refilled. The supply of oxygen is unlimited, and the device is small enough to be moved from room to room. Most oxygen concentrators require a continuous electrical source, and must be plugged into an electrical outlet. However there are portable oxygen concentrators that operate on battery power and may be used for exercise or travel.

Surgery

Lung Volume Reduction

Selected patients with advanced COPD may be candidates for a surgical procedure that can ease the effort of breathing and make walking and other daily activities more feasible. In this procedure, called lung volume reduction surgery, the parts of the lung that are most heavily damaged are removed.

As described previously, the destruction of alveoli in emphysema causes air to get trapped in the lungs. As a result, the lungs become enlarged (hyperinflated). Enlarged lungs can crowd the chest cavity and flatten the diaphragm, making it more difficult to breathe. Removing the hyperinflated portions of the lungs has the effect of improving lung function and quality of life.

The surgery doesn’t cure emphysema, but it helps to relieve symptoms and may prolong life in some patients. However, the surgery is only effective in a minority of patients with emphysema. For this reason, it is very important that patients who are considering lung volume reduction surgery are carefully evaluated by a surgeon with experience in this highly specialized procedure.

Historically, lung volume reduction surgery involved opening the chest with an incision through the breastbone to gain access to the lungs. Today, it is more often done with several small incisions on both sides of the chest. A thin tube with a video camera on the end is inserted through one of the incisions. This allows the surgeon to see inside the body on a video monitor. Surgical instruments are inserted through the other incisions to remove the hyperinflated lung. Regardless of the procedure used, the operation requires hospital stay of five to 10 days.

Due to the risks of surgery, there is interest in trying to develop lung volume reduction techniques using bronchoscopy, a procedure that allows the doctor to view the airways through a thin instrument called a bronchoscope. At this time, the technique is considered experimental and is not available outside of research studies.

Medicare covers traditional lung volume reduction surgery for people who meet certain criteria, and requires that anyone contemplating the surgery first complete a certified pulmonary rehabilitation program.

Lung Transplantation

Lung transplantation may be considered for people with severe COPD who are otherwise healthy. This procedure is generally reserved for people with end-stage lung disease, but no other significant health problems. The criteria generally include an FEV1 of less than 20 percent of what would be predicted in someone without lung disease, as well as very low oxygen levels or very high carbon dioxide levels.

For patients with emphysema, either one or both lungs may be transplanted. The procedure generally results in improved lung function and better quality of life. However, there are risks involved in the surgery, and lung transplant recipients must take drugs to suppress their immune system for the remainder of their lives. These drugs are necessary to prevent the body from rejecting the new organ.

Smoking Cessation

Quitting smoking is an essential step for preventing and treating COPD. But as anyone who has quit smoking or tried to quit smoking can attest, it not so easy to accomplish. People with obstructive lung disease have a powerful incentive to quit smoking, yet many continue to light up. A study from the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention found that 46 percent of adults age 40 and older who have asthma or COPD still smoke.

Cigarette smoking is a powerful addiction, and simply knowing the laundry list of its effects is rarely enough to make smokers quit the habit. About 70 percent of adult smokers report that they want to quit completely, but very few people succeed in permanently quitting on their first attempt. First and foremost, quitting smoking requires motivation. It also requires understanding what you’re up against, and getting the right type of help.

Nicotine Addiction

Nicotine is an addictive substance that acts on regions of the brain that produce pleasurable effects. Nicotine is carried in cigarette smoke into the lungs, where it is absorbed from the alveoli into the bloodstream. From there, it reaches the brain within about seven seconds and binds to receptors called nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, resulting in a release of brain chemicals called neurotransmitters. The primary neurotransmitter released from intake of nicotine is dopamine, which is believed to be linked to the region of the brain responsible for pleasurable feelings. Other neurotransmitters released when nicotine binds to nicotinic receptors also produce effects that reinforce tobacco use. These include stimulation, arousal, improved memory and attention, reduced stress, relaxation, improved mood, faster reaction time, and appetite suppression. Many smokers come to depend on smoking to produce these effects. However, because nicotine levels don’t stay elevated in the blood for very long, the effects are short-lived and more cigarettes are needed to achieve them.

Upon quitting, many smokers report withdrawal symptoms, such as depressed mood, insomnia, irritability, frustration, anger, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, restlessness, decreased heart rate, and increased appetite or weight gain. These are relieved with smoking, making it especially difficult to quit.

The physiologic addiction to nicotine is only part of the story: There also is a large psychological and behavioral component. Smoking becomes a habit, and as such, smokers often associate smoking with certain activities or moods. For example, some people smoke a cigarette after a meal or with a drink, when they feel stressed, or to perk themselves up when they feel down. Smokers also come to associate the pleasurable effects of smoking with the ritual of smoking. They may enjoy just holding a cigarette, the act of lighting it, or the smell and taste of the smoke.

Getting Help to Quit

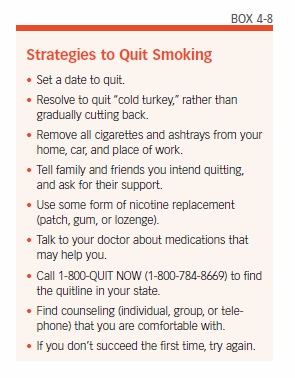

Because smoking is associated with physiological, behavioral, and psychological factors, all three must be addressed when attempting to quit. Studies have shown that some combination of counseling, social support, and pharmacologic therapies usually is necessary. It usually takes more than one try to quit for good—the average is seven attempts—but the benefits are worth it.

It all starts with the decision to quit. Guidelines published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recommend beginning by setting a firm quit date, preferably within two weeks. Some helpful strategies for quitting can be found in Box 4-8, “Strategies to Quit Smoking.” Enlisting the support of family and friends is essential. Some form of counseling—either an individual or group counseling program—is advised. Internet-based chat rooms can also be helpful. Quit lines have been set up in many states (www.smokefree.gov; 1-800-QUITNOW) to connect smokers to relevant resources. Some smokers have been helped to quit with acupuncture or hypnosis. For people age 65 and older, who smoke and have a disease or adverse health effects linked to tobacco use, Medicare Part B will cover smoking cessation counseling. Two smoking cessation attempts are allowed each year, and for each attempt, Medicare will pay for up to four counseling sessions.

Breaking the smoking habit will most likely require coming up with new problem-solving and stress-reducing techniques to replace smoking. For example, it can be helpful to identify situations or activities that increase your risk for smoking, and discuss new types of coping skills with a counselor or fellow smokers who are quitting. Also try to minimize time spent with smokers, to reduce temptation.

Medications That Can Help You Quit

Several types of pharmacologic therapies are available to relieve nicotine withdrawal symptoms:

Nicotine Replacement Therapies

These are available in skin patches, gums, lozenges, inhalers, and as a nasal spray. The patch, gum, and lozenges can be obtained without a prescription. Nicotine gum is not chewed like regular gum—in order for the nicotine to be absorbed, the gum must be chewed a few times, and then held between the cheek and gum.

The nicotine patch maintains a steady blood level of nicotine. This avoids the ups and downs of nicotine levels during smoking, and disrupts the “crave-and-reward” cycle. A step-down program is usually recommended when using the nicotine patch. This program starts with a higher dose of 21 milligrams (mg) per day, which is reduced to a moderate dose (14 mg/day), and finally a low dose (7 mg/day).

E-cigarettes contain nicotine, and some smokers switch to these vapor-producing devices to help them quit tobacco cigarettes. The effectiveness of nicotine replacement therapies such as the gum and patch are established. E-cigarettes are still being studied as an aid to quitting, and two questions remain unanswered: First, are e-cigarettes safe? Second, are they an effective tool for quitting? One study found that smokers who used e-cigarettes were actually less likely to quit smoking than those who never used them.

Bupropion (Zyban)

Bupropion (Zyban), which requires a doctor’s prescription, has been shown to help eliminate withdrawal symptoms. It appears that the drug works best when used in conjunction with one of the nicotine replacement therapies.

Varenicline (Chantix)

This is another drug available by prescription only. Varenicline works by binding to some of the nicotinic receptors, thereby blocking nicotine from binding to these receptors. This results in a reduction in the craving for nicotine, and decreases the pleasurable effects of smoking. Studies have shown the drug to be generally effective at helping people to quit smoking. However, some people who take the drug experience dramatic changes in mood and behavior. The manufacturer advises stopping the drug and contacting a healthcare provider immediately if agitation, depressed mood, changes in behavior, or suicidal thoughts or behavior occur. Some people who use varenicline have a decreased tolerance to alcohol, and get drunk more easily—therefore, people who use the drug are advised to decrease the amount of alcohol they consume.

There are numerous resources to help people quit smoking. Some of these are listed in the “Appendix II: Resources” section. If you try and fail, don’t be discouraged: You are not alone. Perhaps you just need to try a different technique until you find one that works for you.

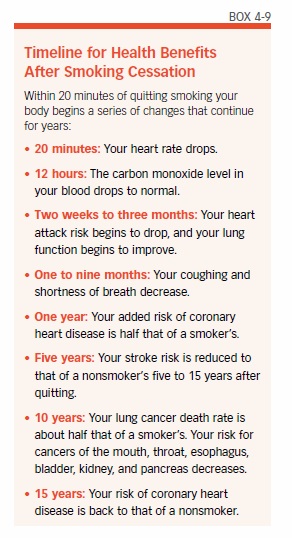

Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation

Some of the benefits of quitting occur relatively quickly, while others can take 10 or more years (see Box 4-9, “Timeline for Health Benefits After Smoking Cessation”). Soon after quitting, blood circulation and lung function begin to improve. Within one to two years, the risk for heart disease decreases. The risk for developing cancer declines with the number of years of smoking cessation.

A large study of more than 104,000 women quantified some of the risk reduction with smoking cessation:

- Those who quit smoking had a 13 percent lower risk of dying from any cause within the first five years of quitting, compared with women who continued to smoke.

- The excess risk of death from any cause reached the level of never-smokers 20 years after quitting.

- Much of the reduction in the risk of dying from heart disease was realized within the first five years.

- Five to 10 years after quitting, death from any type of lung disease was reduced by 18 percent. After 20 years, it reached the level of never-smokers.

- About 64 percent of deaths among current smokers and 28 percent of deaths among former smokers were attributable to cigarette smoking.

- Lung cancer mortality was reduced 21 percent within five years of smoking cessation. It took 30 years to completely eliminate the excess risk.

Lifestyle Tips to Maintain Lung Function

In addition to quitting smoking and taking prescribed medications, people with COPD can take steps to improve their health and possibly slow down the damage caused by the disease. Strategies include eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, learning special breathing techniques, and making changes in day-to-day life, among others. Even staying cool can have important benefits: One study found that high indoor and outdoor temperatures were linked to more symptoms. Being in hot indoor environments also worsened lung function.

Healthy habits are recommended for everyone, but are especially necessary for those with chronic lung disease.

Eat Right

Your body needs the energy provided by food to function, and that includes breathing. In fact, oxygen is a necessary part of the process of breaking down food into energy (called metabolism). Energy, in turn, is needed for the process of breathing. For people with COPD, difficulty breathing may make it difficult to eat properly, creating a downward cycle that can lead to malnourishment and even greater breathing problems.

About one-third of people with COPD are malnourished, and experience weight loss. Malnutrition can worsen lung function and also compromise the immune system. A compromised immune system can render a person with COPD susceptible to infections and other illnesses.

It is extremely important for people with COPD to consume the recommended number of calories, and try to maintain a healthy weight. If you are underweight, it means your body has fewer stores of energy to draw from. Being overweight also can be problematic, since carrying extra weight means the heart has to work harder, which makes breathing more difficult.

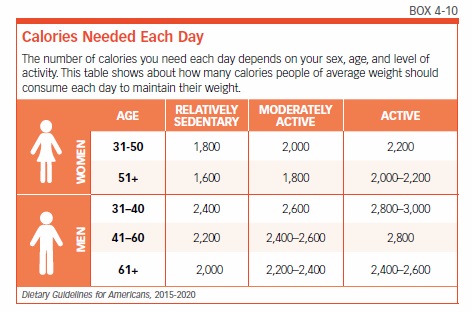

A well-balanced diet that provides an adequate number of calories is necessary for good health. The recommended caloric intake varies by age and level of activity (see Box 4-10, “Calories Needed Each Day”).

Keep in mind that people with COPD expend extra energy in the simple act of breathing. For a person with COPD, the act of breathing may burn 10 times as many calories as it does for someone without lung disease. This means that even more calories may be required to maintain proper weight.

Foods to Prioritize

The source of calories is important. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has established sound nutrition guidelines, which are available at www.choosemyplate.gov. You might also consider consulting a registered dietitian who specializes in COPD and can work with you to develop an individualized food plan.

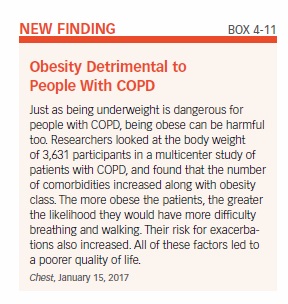

The USDA recommends consuming foods and beverages that are rich in nutrients and come from the basic food groups. Try to avoid foods with little nutritional value that supply only empty calories, as this can cause you to become obese, yet malnourished (see Box 4-11, “Obesity Detrimental to Patients With COPD”). Your diet should emphasize fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and dairy products. The diet should also include protein from lean meats, poultry, and fish, along with beans, eggs, and nuts. Try to limit your consumption of saturated fats, trans fats, cholesterol, salt (sodium), and sugar. Sodium is particularly problematic because it can cause fluid retention, which can interfere with breathing.

One study found that people with COPD who ate a healthy diet that included fish, grapefruit, bananas, and cheese had better lung function and fewer symptoms than those who did not eat these foods. The researchers noted that these particular foods may not by themselves be the key to improved health—rather, eating them indicates the person most likely eats an overall healthy diet that includes fish, fruit, and dairy products.

Foods to Avoid

Avoid foods that cause gas or bloating, as this can make breathing more difficult. Gas-producing foods include broccoli, cauliflower, beans, and carbonated beverages.

Other Diet Tips

Drink plenty of fluids, which help to thin mucus and make it easier to cough up. Try for six to eight glasses (eight fluid ounces each) per day. Water, milk, and fruit juice are the best sources, but coffee, tea, and soft drinks also count. Alcoholic beverages, such as wine and beer, contribute to fluid intake, but should be consumed only in limited amounts.

If breathing problems make eating difficult, try eating four to six small meals a day, rather than three large ones. You might also try eating the largest meal early in the day, so that you have more energy for the rest of the day. Take your time preparing meals, and choose foods that are easy to prepare. You don’t want to expend too much energy making a meal, only to have little energy left to eat it. Eat slowly, in a relaxed setting. Digestion requires energy, so wait an hour or more after eating before engaging in activities.

Exercise Regularly

People in all stages of COPD experience a decline in their ability to engage in physical activity as the disease worsens. Although it may seem difficult to exercise when breathing is a problem, regular exercise can actually improve lung function. It also keeps muscles strong, and improves overall health. A recent study of people with COPD found that those who got no exercise at all were less able to be physically active and had weaker muscle strength compared with people who were at least somewhat physically active.

If you feel daunted by the idea of exercising, keep in mind that the level of exertion required is relative to your health and ability. You don’t need to be an athlete to benefit from exercise—in fact, you should begin by having a discussion with your doctor to determine the most appropriate type of exercise and level of intensity.

If you’ve been in a pulmonary rehabilitation program, continue the exercises on your own after finishing the program. If you haven’t been in one of these programs, be sure to increase your physical activity slowly from your present level. Walking and swimming are good ways to get exercise without overexerting yourself. Try to walk a little farther and for longer periods each day. Try to work up to 20 to 30 minutes of physical activity three to five times a week. The key is to do it on a regular basis (daily, or at least several times each week). Research has shown that increasing physical activity decreases hospitalizations due to exacerbations of COPD. One study found that people with COPD who engaged in any regular exercise were about one-third less likely to be readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of being discharged. The benefit was greatest for those who exercised 150 minutes or more a week.

Before beginning an exercise, warm up your muscles by doing some stretches. If walking is your chosen activity, start at a slow pace and gradually walk faster. It may help to walk or exercise with friends, making it a social occasion. Be sure to go at your own pace, and don’t compare yourself to anyone else. Keep a diary to record your exercise goals and track your progress.

Control Your Breathing

Breathing techniques, such as pursed-lip breathing and diaphragmatic breathing, can help to make the most of every breath you take. Talk to your physician or respiratory therapist about these techniques to find out if they might be useful for you.

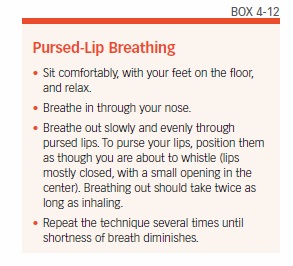

Air that gets trapped in the lungs can cause shortness of breath. Air trapping can occur from breathing too fast, or because airways are narrowed, and alveoli are damaged. Pursed-lip breathing slows the pace of breathing and increases air pressure in the lungs, which helps the airways stay open. If you feel short of breath from exertion, stop for a few minutes and practice pursed-lip breathing to get fresh air flowing into your lungs (see Box 4-12, “Pursed-Lip Breathing”).

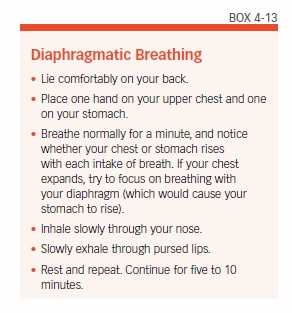

Diaphragmatic breathing facilitates deeper breathing. The diaphragm is a dome-shaped muscle in the abdomen that is involved in the mechanical process of breathing. In people with COPD, the diaphragm and other muscles involved in breathing can weaken. Using a diaphragmatic breathing technique (see Box 4-13, “Diaphragmatic Breathing”) can help to strengthen these muscles, slow down your breathing rate, increase your blood oxygen levels, and allow you to use less effort to breathe.

Breathe Clean Air

Keep the air in your home as clear of irritants as possible. For example:

- Don’t smoke, and don’t allow anyone else to smoke in the house.

- Keep all fumes and strong smells out. This includes air fresheners, scented candles, and fragrant cleaning products.

- If you must have painting done, stay out of the house until it is finished.

- Avoid smoke from wood fires.

Travel Comfortably

Having a chronic lung disease such as COPD may require making special arrangements for traveling, particularly by airplane. Those who require oxygen therapy will first need to obtain permission from their physician to fly. They must also notify the airline in advance of travel to arrange for using oxygen during the flight.

Some people who don’t require oxygen therapy at home may need supplemental oxygen while flying. This is because the air pressure inside an airplane cabin is lower than it is on the ground, especially when the airplane is taking off and landing. Low air pressure decreases the amount of oxygen in the air. People without lung disease can adapt to the changes in air pressure, but for a person with severe COPD, even a small change in air pressure may cause an exacerbation of symptoms.

Always discuss air travel plans with your physician. Blood oxygen measurements will likely be needed to determine whether supplemental oxygen will be required. The doctor will also need to provide a letter to the airline. During the flight, the oxygen will be provided by the airline (likely at a fee). Passengers are not allowed to bring their own liquid or gas oxygen canisters on board an airplane. However, some airlines allow patients to use their own portable concentrators during flights. Empty cylinders and equipment likely are allowed only as checked baggage.

Information about which airlines allow use of oxygen on flights, along with their policies, is available from the Airline Oxygen Council of America (see Appendix II: Resources).

Relax and Take Care of Yourself

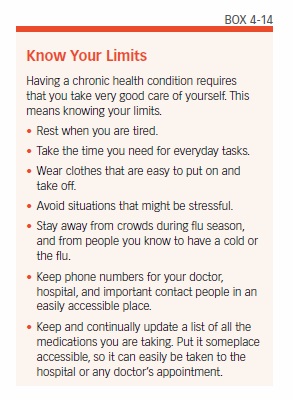

Anxiety, stress, and fatigue are common in everyday life and can lead to health problems even for otherwise healthy people. For people with COPD they can exacerbate the condition, leading to worsened lung function, infections, and other health problems (see Box 4-14, “Know Your Limits”).

Coping with COPD may feel overwhelming at times. Sharing feelings and concerns with loved ones and asking for their help may ease some of the burden. Joining a support group for people with COPD may be even more helpful. The American Lung Association (see Appendix II: Resources) is a good resource for finding a local support group.

The post 4. Treating COPD appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 4. Treating COPD »

Powered by WPeMatico