3. Choose The Right Program

There is not a “one-size-fits-all” program of aerobic fitness. Instead, dozens of methods and combinations of methods have been proven effective.

The key is to find a program that works for you, one that takes into consideration your age, health status, physical condition, personality, fitness goals, and living circumstances. This chapter discusses the most popular forms of aerobic fitness programs and helps you choose the best fit. If you try one and don’t like it, try another, or try a combination of physical activities that help you get into that magic target heart rate zone, and sustain it for 20 to 30 minutes.

Where to find a program

Finding these programs shouldn’t be a problem. Most of them can be done at home or in your neighborhood. They are available in almost every format imaginable, including print, television, websites, videos, and smartphone apps.

Commercial programs have names like Jazzercise, Zumba, Silver Sneakers, and Cardio Tennis. Non-profit organizations like the Arthritis Foundation and American Heart Association, as well as government agencies (Veterans Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institutes of Health) all offer programs.

If you prefer exercising with others, and with the supervision of a trained exercise instructor, here are some places where you might find programs.

- Local/regional hospitals

- YMCAs/YWCAs

- Churches/synagogues

- Fitness/wellness centers, gyms

- Physical therapy clinics/facilities

- Municipal recreation centers

- Senior/community centers

- Colleges/universities

- Workplace wellness centers

Walking

Of all aerobic activities, walking is the most natural, convenient, inexpensive, and probably the safest. If you decide to start walking for exercise, you won’t be alone. Exercise walking is the number one form of physical activity in the U.S., with more than 93 million people reporting that they walk for exercise at least once a year—not exactly a commitment to aerobic fitness, but it’s a start.

Turning an occasional activity into an aerobic exercise is simply a matter of walking more often, faster, and for periods of time that eventually add up to 30 minutes or more a day, at least five days a week.

Walking is also the easiest way for a previously sedentary individual to get started on an aerobic exercise program.

Walking at the right pace and length of time can provide the same kinds of benefits bestowed by other, more rigorous activities. A 2013 study involving thousands of subjects of all ages found that brisk walking can lower the risk of cardiovascular conditions as much as running (see Box 3-1, “Moderate-intensity walking can lower the risk of heart conditions as much as running”).

Previous studies have linked walking with improved energy, sleep, flexibility, posture, skin, and memory, lower cancer risks, better weight control, and even increased creativity (see Box 3-2, “Walking improves creative output by 60 percent”).

How fast? How far?

The average speed for fitness walking is between 3.0 and 3.5 miles per hour, but the pace depends on the person’s age, gender, fitness level, as well as terrain. As with other aerobic activities, the pace and distance are not as important as getting your heart rate into the target heart rate zone and keeping it there for 20 to 30 minutes at a time (three 10-minute walks per day, two 15-minute walks, or one 30-minute walk, plus warm-up and cool-down times).

Step-by-step

The 10,000 steps program has been successful in motivating millions of people to walk. Ten thousand steps a day is about five miles, although the number of steps is based more on a number people can remember. It seems to work—all you need is a pedometer and some good walking shoes to get started. Remember: Walking shoes should be light, flexible at the base of the toes, and have extra shock absorption in the heel and under the ball of the foot.

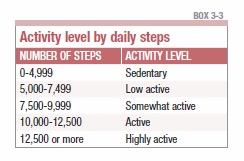

First, determine your usual activity level. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) suggests that you wear a pedometer for a week without altering your routine. Use Box 3-3, “Activity level by daily steps,” to classify your current activity level.

According to The Walking Site, if you average 3,000 steps per day now, your goal for the first week should be 3,500 each day. The goal for the second week is 4,000 steps each day. Continue to increase the total each week and you should average 10,000 steps a day by the end of 14 weeks.

Ten thousand steps, although an admirable goal, may not be practical or possible for some people. At least one ACSM expert suggests that 7,500 steps may be a more reasonable number, and adds that the goal of 150 minutes of activity per week is consistent with most fitness guidelines.

Adding steps

Try increasing the number of steps you take each day.

- Take a walk with a friend or family member

- Walk the dog

- Use stairs instead of elevators

- Park farther from stores

- Plan walking (instead of sitting) meetings

- Take walking breaks at work

- Walk to local businesses instead of driving

Hot spots and remedies

Although the risk of injury while walking is low, it exists. The most common injuries are blisters, shin splints, and muscle cramps. Wear cushioned and supportive shoes and socks (see page 30). Keep your feet as dry as possible, and be sure your shoes are not rubbing against any part of your foot. Try not to walk on concrete sidewalks, at least not at first. Instead, begin on asphalt, a track, or hard/wet sand, all of which are softer. At the beginning of your new walking program, stay on flat surfaces and gradually work up to hills.

Jogging/running

These two activities are often paired together, but they are different. Jogging is often defined as moving at a speed slower than 6 miles per hour, while running is any speed faster than that. Which one you choose to do depends on your fitness level and ability. Many older adults often begin with jogging and gradually progress to running. Both activities offer all of the advantages of walking, but at a higher intensity level. Their benefits are well documented, and for many people it takes as little as 10 minutes a day to get positive health results (see Box 1-8 in Chapter 1, page 13). Like walking, all you need is time, a place to jog or run, and a good pair of well-fitted running shoes.

Jogging and running versus walking

Jogging and running gives you two advantages over walking. The first is that it allows you to expend energy in a shorter period of time. Simply stated, it takes longer to walk a mile than to run or jog one. Running for 20 to 30 minutes is the equivalent to walking 40 to 50 minutes. For younger adults, brisk walking may not raise the heart rate into an optimal training zone. That’s not usually a problem with middle-aged and older adults.

One of the most compelling arguments for jogging came in the Copenhagen City Heart Study, which found that joggers had a five- to six-year longer life expectancy than the average population (see Box 3-4, “Joggers have a longer life expectancy than the average population”).

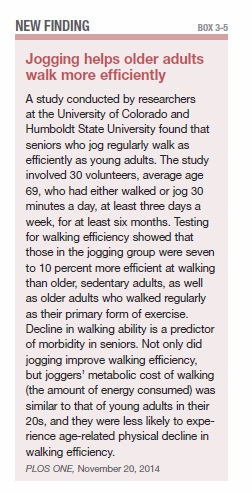

Another study published in November 2014 found that seniors who jog regularly walk as efficiently as younger adults (see Box 3-5, “Jogging helps older adults walk more efficiently”).

Jogging and running are high-impact exercises, as opposed to low-impact (one foot always on the ground) activities, and they require a higher degree of dedication. One study showed that 50 percent of people who begin a jogging/running program drop out, compared to 20 percent of those in a walking program.

Risks

With the added advantages of jogging come risks. Joggers and runners have a higher risk of injuries than walkers, and the risk increases with the frequency and duration of running. Every time a jogger’s foot hits the ground, the impact is three to four times his or her body weight, as compared to the surface impact of walking. One study showed that as many as 66 percent of joggers and runners sustain an injury during a one-year period.

Hot spots and remedies

The most common running injuries are shin splints, plantar fasciitis, cramps, neck and back pain, and blisters. UCLA physical therapists recommend a dynamic warm up and static stretching cool down as part of a jogging/running program that focuses on calves, hamstrings, quadriceps, and core (see pages 52 and 53 for static stretching exercises that address these areas.)

From walking to jogging

If you decide to embark on a jogging or running program, work into it gradually. Begin with a basic, but challenging, walking program, then progress to a walking program that includes interval workouts, and then graduate to a walk/jog program that safely gets you into the aerobic fitness zone. Sample programs are on page 58.

Swimming

Swimming is the fourth most popular sports activity in the U.S., and a good way to get regular aerobic activity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Here are some other CDC facts about swimming:

- Just two and a half hours per week can reduce the risk of chronic illness

- Swimmers have about half the risk of death compared to inactive people

- People report getting more enjoyment out of water-based exercise than exercising on land

- People can exercise longer in water than on land without increased effort or pain in joints or muscles

Drawbacks

Although an excellent method for becoming aerobically fit, swimming has its drawbacks. For most people, it takes time, effort, and possibly monetary expense to use a pool. And swimming laps, as opposed to other water-based activities, can be a solitary, even boring way to exercise for those not used to exercising or exercising alone. Finally, although swimming is an aerobic activity, it is not a weight-bearing exercise and doesn’t promote bone health (it doesn’t harm bone health—it just doesn’t contribute to stronger bones).

Hot spots and remedies

The problem areas for swimmers are the shoulders and neck, in addition to fatigue and soreness. Avoid these potential injuries by mimicking the swimming motion with your arms as part of a dynamic warm up before getting into the water. Also include neck range-of-motion exercises.

Cycling

Riding a bicycle outside or a stationary bike inside, although not the most popular form of physical activity for adults, certainly qualifies on two counts: the aerobic challenge and ease of accessibility.

Benefits

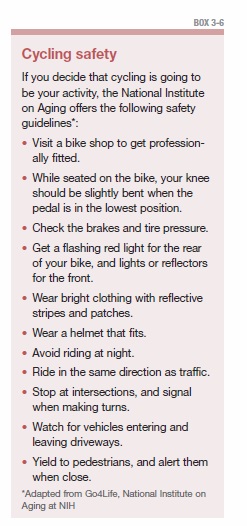

Cycling is low impact, but is great for allowing you to control the frequency, intensity, and duration of your workouts. In addition to cardiovascular endurance, riding a bicycle also offers strength, flexibility, and balance training. Cycling does require some basic skills, including knowing some basic safety guidelines (see Box 3-6, “Cycling safety”).

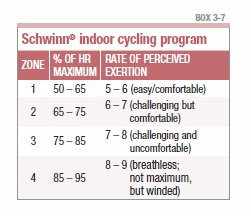

Cycling programs for beginners and older adults are limited, but there are some you can follow for all-around aerobic fitness. For instance, the Schwinn® Indoor Cycling Program recommends a cardiovascular training program based on numbered intensity zones (see Box 3-7, “Schwinn® indoor cycling program”). Beginning and older exercisers should not get into zones 3 or 4 without consulting their doctors first. Many gyms also offer low-intensity spinning/indoor cycling classes for beginners and older adults.

Hot spots and remedies

Typical hot spots for cyclists are the neck, back and wrists. Saddle soreness and overall muscle fatigue also are common. Dynamic warm ups and cool downs can help avoid problems and injuries to the quadriceps, hamstrings, calves, and abdominal muscles.

Water aerobics

If you are comfortable in the water, but want a more varied exercise routine than swimming laps, water aerobics might be the right fit. This activity can build muscle tone, expend calories, and increasing aerobic capacity. Water aerobics is particularly helpful for people with medical conditions like arthritis because exercises performed in water place less stress on the joints. Water provides resistance (and thus, strength training) in every direction, and water exercises can be designed to fit individual needs.

Finally, you don’t have to know how to swim to participate in a program, and most people do water aerobics in groups, so you get both physical and social benefits.

Variety of programs

The variety of exercises and programs is almost endless. For example, one Midwestern YMCA offers the following water-based choices:

- Aqua Arthritis

- Aquacise

- Aqua Pump

- Deep Water Aquacise

- Golden Aerobics

- Mobility in Motion

- Shallow Water Aerobics

- Water Strength and Endurance

What to wear

Wear something that will streamline your movement in the pool. T-shirts and baggy pants cause too much drag. A one- or two-piece swimsuit works best. Your feet might need arch support, and some companies make aqua sneakers that have holes for water drainage. An old pair of gym shoes might offer the same support, but wash them before getting into the pool and use them only during water workouts.

A typical program moves the participant through a progressive sequence beginning with a warm up to a peak intensity period, and finishing with a cool-down session. Choose exercises you like, and add more later on for variety.

Water exercise options

Sample water aerobic exercise programs appear on page 59. For these workouts, move or push through the water, but only at a speed you can manage with control (without wavering or losing your stability).

Suggestions for repetitions and sets are for structure, safety, variety, and strength training, not necessarily aerobic fitness, which requires a heart rate in a target zone for an extended period of time. However, it’s possible to improve strength, flexibility, balance, and cardiovascular fitness by doing the same exercises.

Hot spots and remedies

The whole body will be involved in water aerobics, so any area may have its share of normal muscle soreness. Warm up with calisthenics and out-of-water movements that you’ll be doing in the water. Take it slow. Begin with a few repetitions and one or two sets, then gradually work your way up to eight to 10 repetitions and two to three sets.

Dance aerobics

More than 20 million Americans participate in aerobic exercise classes and many of them choose aerobic dancing. It is typically a one-hour workout that combines floor exercises and dance movements set to music. The hour should include a five- to 10-minute warm up and cool down.

One of the first and most popular dance programs was Jazzercise. It was introduced in the 1970s and is still out there in multiple platforms. According to its supporters, Jazzercise is “a fusion of jazz dance, aerobic exercise, resistance training, Pilates, yoga, and kickboxing.”

There have been hundreds of variations since the aerobic dance explosion of the 1980s, but one that has been especially popular over the past decade is Zumba. It is, according to the Mayo Clinic, “a fitness program that combines Latin and international music with dance moves.” Zumba routines incorporate alternating fast and slow rhythms with resistance training. It would be classified as moderate aerobic activity for younger adults; moderate-to-vigorous for older exercisers.

A small study conducted at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and reported in the Journal of Sports Science & Medicine found that all participants in a Zumba experimental group reached ACSM aerobic exercise guidelines for percentage of heart rate maximum, with an average of 79 percent.

Pros and cons

The advantages of dance aerobics are a solid, supervised aerobic workout, added enjoyment because of the music component, and exercising in the company of others if you join a group. Exercise is repetitious and can be boring, but that’s not a problem in dance aerobics. The physical activity, group setting, and upbeat music tend to keep people engaged.

Perhaps the greatest advantage of dance aerobics is that you can participate in a class or group environment, or you can exercise at home, alone, and at your own pace with DVD programs.

The disadvantages, or perhaps obstacles, of group dance aerobics are identifying a program, being committed enough and able to get to a gym or fitness center on a regular basis, and doing the physical work required of aerobic dance. It is a challenging form of exercise, but all aerobic exercise should be challenging.

High-impact, low-impact

Be sure to ask about the level of the group you are considering and whether the exercise is low-impact, high-impact, or high-low. Low-impact aerobics focus on a less demanding cardiovascular load over a longer period of time. One foot is always on the ground.

High-impact exercises get your heart rate closer to 80 to 85 percent of maximum level, but can involve stepping up on a platform, jumping, hopping, or other moves in which there is a greater impact on the bones and joints. Walking is low impact. Jogging, running, and in some cases, dance aerobics, are high-impact exercises.

High-low aerobic exercise combines both high and low impact moves, with the goal of getting you up, moving, and into the target heart rate zone.

If you are beginning a program, start with one that is low-impact, then decide if you want to stay at that level or move to a more aggressive routine. And remember, with dance aerobics, you do not have to do the movements perfectly. If you cannot keep up at first, it’s okay to march or jog in place until you can pick up the next move.

Step aerobics

Step aerobics is similar to dance aerobics, but requires you to step up and down on low platforms or boxes that range from four to 10 inches in height. The idea is to keep one foot on the ground, which is supposed to classify step aerobics as low-impact, but for some it may be a more challenging form of aerobics than dancing. Step aerobics falls somewhere between moderate to vigorous intensity.

A study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning examined the effects of a 12-week step aerobic training in a group of women with an average age of 63. The programs had a positive effect on waist circumference, upper and lower body strength, and cardiorespiratory fitness, among other measurements.

Hot spots and remedies

The higher the impact of aerobic exercises, the higher the injury rate. Among the most common injuries are plantar fasciitis, shin splints, stress fractures, and Achilles tendon and calf pain. There is also a higher risk of falling with step aerobics.

Shoe selection, warming up, starting slowly and gradually increasing exercise intensity, frequency, and duration can reduce the risk. Adding strength, flexibility, and balance training to your comprehensive fitness program will further reduce the risk of all injuries even more.

Sports

Team and individual sports present a problem for middle-aged and older adults in terms of aerobic fitness. They either require too many people to play or, more importantly, don’t provide enough continuous activity at an intensity level strenuous enough to get your heart into your target heart rate zone.

Some sports are relatively popular with older adults (golf and bowling, for example) and provide fitness benefits, such as flexibility, mobility, balance, and strength, but the cardiovascular component is simply not there (although golfers can get a better workout if they walk instead of riding in a cart).

Tennis is one sport that can be aerobically beneficial, but there are restrictions. Even though singles is a stop-and-go game, it is considered an aerobic activity for most people. But it’s also a high-impact activity, especially on hard courts, and some exercisers are better off doing low-impact aerobics for safety and injury prevention. Doubles in tennis provides a lower-impact workout, but in most cases does not reach the aerobic standard.

If you are a tennis player looking for a cardiovascular workout, consider a program called Cardio Tennis. It is a series of group lessons and activities that feature drills, a high-energy workout, player-friendly tennis balls, music, and heart rate monitors. Cardio Tennis is taught by a trained instructor, usually with a group of six to eight players, and includes a warm up, aerobic exercise segments, and a cool down. The emphasis is on aerobic activity more than tennis instruction, although you get some of both. Go to www.cardiotennis.com for more information.

Exercise machines

Exercise machines mimic almost every sport and physical activity, and most can be incorporated into an aerobic exercise program. Depending on the machine, they can improve strength, power, flexibility, balance, and aerobic capacity.

All have disadvantages, however, including:

- Expense

- Repetitious nature of exercise machines that can lead to injuries,

- Boredom factor, which can result in some people using them less frequently or not using them at all

- Inaccurate feedback features

Any estimate of exercise intensity, calories burned, and other measurements depend on factors that machines cannot process (age, gender, health, and physical condition). You’ll have to decide whether the advantages outweigh the disadvantages.

Elliptical trainers

These are low-impact, safe for people with range-of-motion problems, and allow upper and lower body exercise simultaneously, but they are not weight-bearing and do not build strength.

Rowing machines

These are particularly good for upper-body strength and flexibility. Although they involve low-impact exercise, they can easily get you into your target heart rate zone. However, they are not the best choice for people with back problems. Other “hot spots” are the knees and shoulders.

Treadmills

Treadmills are speed-adjustable for walkers, joggers, and runners. Other than changing speed and incline, treadmills don’t offer much variety—there also is an increased fall risk when using a treadmill. Still, they are a staple exercise machine at most gyms and fitness centers and thus, easily accessible.

Recumbent cycles

These are low-impact, take pressure off the back and legs, and give you support that other machines don’t. They also leave your hands free, allowing you do other tasks. Unlike stationary bicycles, you cannot use your full body weight (or stand), so pushing the pedals can be harder. That’s an advantage for some, a disadvantage for others.

Stationary bicycles

Stationary bicycles are easy to use, convenient, not dependent on weather, and allow you to watch TV while exercising. They primarily exercise the legs and can get boring in a hurry. Stationary cycling at a moderate pace burns 450 to 500 calories per hour, depending on your weight.

Ergometers

Ergometers are used to strengthen and condition either the upper or lower body, and to get a cardiovascular workout by using only your arms or legs. They are used more in physical therapy settings, but can be found in many fitness facilities or gyms. They can be used to give your arms or legs a break, and for warming up. The machines can be an ideal choice for people with mobility issues or who are returning to exercise after an injury or long layoff.

Steppers

These are calorie-burners (as much as 600 per hour for a person who weighs 150 pounds). They are also an effective cardio exercise and are considered a more challenging workout than elliptical trainers. Steppers, however, involve impact and put a greater strain on knee joints than ellipticals.

Back to basics

The average person is not going to do basic calisthenic-type exercises for 30 minutes or more at a time. But people who prefer to accumulate their 30 minutes or more of aerobic exercise per day in 10-minute bursts might consider combining some basic body weight exercises. They include push-ups, step-ups, marching or jogging in place, jumping jacks, and lunges. None of them will work unless they get your heart rate into your target zone. Warm up for body-weight exercises as you would for any other aerobic activity.

Up next

People who exercise occasionally injure themselves. Chapter 4, “Minimize Injuries,” describes the most common injuries, how to treat them, and better yet, how to prevent or minimize exercise-related bumps and bruises.

The post 3. Choose The Right Program appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 3. Choose The Right Program »

Powered by WPeMatico