4. Hydration

Why You Need Water

Without water, you can live only a few days. No other nutrient is as essential to the body. Between 45 and 75 percent of a person’s body weight is water. Water plays critical roles in your body, such as transporting nutrients, lubricating joints and body tissues, facilitating digestion, and maintaining blood pressure and circulation. Water helps maintain normal body temperature, primarily through sweating, and prevents the body from overheating during exercise, especially if the weather is hot. Adequate water also is needed to enable your kidneys to remove waste products so you can excrete them in urine.

Dehydration results when you don’t take in enough fluid or you lose too much fluid (see Box 4-1, “Fluid Balancing”). Risk of dehydration increases with physical activity. When you become dehydrated, the volume of blood circulating through your body decreases and your blood becomes thicker, so blood flow becomes sluggish. As a result, your blood is less able to deliver oxygen to muscles, carry away waste materials, and help rid the body of excess heat. Water for sweat comes from the blood, so with less blood circulating, you have less water available for sweat, and as your ability to sweat decreases, your body temperature goes up. At the same time, your heart rate increases in an effort to help push the blood to your exercising muscles and vital organs, such as your brain and lungs. For every 1 percent of body weight lost due to dehydration, heart rate increases by 5 to 8 beats per minute and core body temperature increases by 0.18 to 0.72ºF.

Dehydration also can contribute to many common health concerns, such as constipation, falls, urinary tract infections, and kidney stones. Mental performance takes a hit when you’re dehydrated, too. Dehydration can impair memory, math ability, and mood. It also can impair the mental activity needed to support physical movement and hand-eye coordination. Emerging evidence suggests dehydration may increase risk of free radical damage in the body’s cells and tissues, which can contribute to chronic disease risk.

How Much Do You Need?

Most people have heard the rule of thumb that everyone should consume eight 8-ounce glasses of water per day. The basis for this recommendation is uncertain, and although this amount of water might be enough for some sedentary adults, it doesn’t really account for differences in body size, physical activity, or environmental factors, such as hot conditions or high altitude. The Dietary Reference Intakes specify that the Adequate Intake level (which covers the needs of most people) for water is 12 cups or 95 ounces per day for women and 16 cups or 130 ounces per day for men. Your individual needs likely differ a bit from these broad guidelines though.

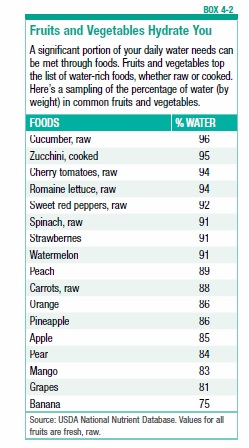

When evaluating water intake, what many people overlook is that part of their water quota is met through sources other than fluids or beverages, including fruits and vegetables, soup, cooked cereal, and other foods. Fruits and vegetables generally are the biggest sources of water from solid foods (see Box 4-2, “Fruits and Vegetables Hydrate You,” on page 38). Even foods you wouldn’t think contain water, such as cooked brown rice or whole-grain pasta, fish, poultry, and eggs contribute to your water intake. Additionally, when you eat food, it typically triggers you to drink fluids, which also supports hydration. One recent study of independent-living older adults (aged 60 to 83) found that 92 percent were adequately hydrated, based on a 24-hour urine sample, and about half of their water intake was estimated to come from food, based on a 24-hour recall of what they had eaten and drunk. Other estimates suggest people get 20 to 30 percent of water from food, on average.

Neither too much water nor too little water is good for the body. Although it’s important to be hydrated for exercise, over-hydration should be avoided, as this can lead to abnormally low blood sodium levels (hyponatremia) during exercise. In other words, excess fluid intake can dilute sodium too much in the body. Hyponatremia can lead to symptoms such as headache, confusion, dizziness, nausea and/or vomiting, weight gain, muscle cramps, and weakness; in some cases hyponatremia is life threatening. For further details, see Box 4-3, “Prevalence of Hyponatremia.”

Age-Related Hydration Changes

The amount of water in the body decreases by approximately 15 percent between the ages of 20 and 80. This puts an older person at greater risk of dehydration from small losses of water. Additionally, adults over age 60 generally are less heat tolerant than younger adults when it comes to exercise-related heat stress and tend not to feel as thirsty, so they typically are more dehydrated when thirst is triggered compared to a younger person.

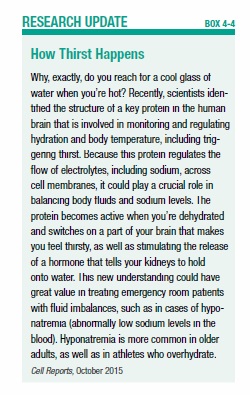

Our sense of thirst is the body’s way of prompting us to drink fluids to maintain adequate hydration levels. It involves receptors in the brain that monitor sodium levels and receptors in blood vessels that can detect changes in blood volume and blood pressure. When your body loses more water than you take in, thirst is triggered. Additionally, the body releases a hormone that tells the kidneys to reduce urine production, thus conserving water. With age, the body’s ability to concentrate urine decreases—and you may find yourself visiting the restroom more often. These changes increase risk of dehydration in older adults.

Risk of dehydration also can increase in certain disease states, such as diabetes and hypertension (high blood pressure). In some cases, dehydration is partly due to medications, such as diuretics and laxatives, used to treat health conditions. Scientists continually are learning more about how thirst and hydration are regulated, and this may help in the treatment of dehydration (see Box 4-4, “How Thirst Happens”).

Assessing Hydration

Someday, you may be able to monitor your hydration status with a wristband that tracks sweat loss (see Box 4-5, “Wearable Sweat Sensors”). In the meantime, you’ll have to use lower-tech methods to keep tabs on your hydration. Following changes in body weight from day to day and after exercise provides a way to determine changes in hydration status, as weight fluctuations within short time periods are generally due to changes in water content of the body (not fat loss). If you weigh yourself first thing every morning after urinating and your body weight fluctuates by less than one percent from day to day, it’s a sign you’re adequately hydrated. Similarly, if you weigh yourself before and after exercise, it can give you an idea of your hydration status, assuming you began exercise well-hydrated.

Generally, losing just 2 percent of your body weight during exercise—that would be 3 pounds for a 150-pound person—is enough to impair endurance exercise performance and cognitive function, especially in hot weather. However, one study found that exercise-induced dehydration of up to 2.3 percent of body weight actually improved performance, possibly because the body was a little lighter, thus taking less effort to move it. So, there might be a little leeway in trained athletes. A decrease in body weight between 3 and 5 percent after exercise represents significant dehydration. In cool weather, it may take fluid losses in this higher range before physical performance is impaired. For a more detailed discussion of dehydration symptoms based on the percentage of water loss, see Box 4-6, “Dehydration Symptoms Based on Percent Body Weight Water Loss,” on page 41.

Although checking the color of your urine throughout the day is commonly promoted as a way to evaluate how well hydrated you are, recent evidence suggests it’s really not a very accurate indicator of hydration status, especially in the general public. For professional athletes, limited evidence suggests the first morning urine color might be a reliable way to assess hydration. The idea is that if your urine is pale yellow (similar to lemonade), you’re well hydrated. If your urine is darkly colored (similar to apple juice) and limited in volume, you may be inadequately hydrated. Many factors can interfere with the results. For example, some medications and vitamin supplements can discolor urine. Certain foods, such as beets and rhubarb, can temporarily discolor urine in some people, too. For other dehydration signals, see Box 4-7, “Possible Signs of Dehydration.”

Maintaining Hydration

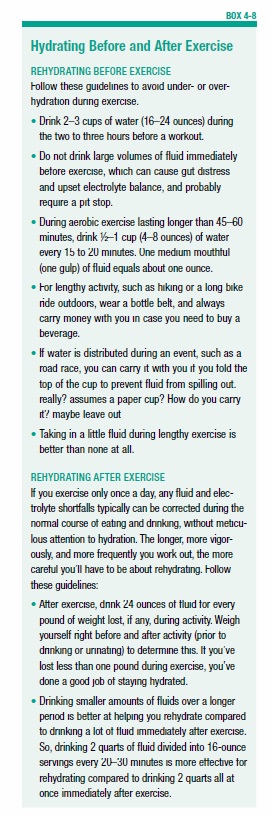

When you’re preoccupied with physical activity, you may not think about the fact that you’re thirsty. Even if you do tap into your thirst level, fluid may not be readily available unless you planned ahead. So, it’s important to hydrate before exercise, plan for hydration during longer and/or more vigorous exercise sessions, and rehydrate afterwards. For guidance on hydration, see Box 4-8, “Hydrating Before and After Exercise,” on page 42. When you go into exercise adequately hydrated, you are more likely to have a lower core body temperature and heart rate during exercise.

The environment in which you’re exercising can have a big impact on fluid and electrolyte balance in your body. For example, extremes of temperature and high altitude increase your body’s need for water and electrolytes to replace the extra fluid lost in such conditions. In hot weather, a 10ºF increase in temperature can cause a 50 to 60 percent increase in water requirements at rest. If you’re exercising or working hard in such hot weather conditions, your water needs will increase well beyond this amount.

Although you may not think about water loss when you’re exercising at a colder, high altitude, you lose about twice the amount of water just through breathing than you would at sea level. Because there’s less oxygen in the air at higher altitudes, you breathe deeper and more rapidly. Additionally, when you’re exercising in cold conditions, your sense of thirst is blunted, and you may not think to hydrate as you would in hot weather conditions. Plus, you may sweat more if you over-dress in cold weather, and cold weather may trigger increased urination. So be especially aware of hydration in such conditions, especially if you’re not acclimated to them.

Sports Drinks

Plain water is calorie-free and hydrating. If you’re sweating lightly or exercising for an hour or less, plain water generally works just fine for hydrating. Despite this, there is heavy promotion of sports drinks, such as Gatorade and Powerade, which are a billion dollar industry. Although people use these drinks for many different reasons, their best use, if at all, is by those who are doing moderate to vigorous intensity exercise lasting longer than 60 minutes. These drinks contain sweeteners (typically sugar, dextrose, and/or high fructose corn syrup) and electrolytes, primarily sodium and a bit of potassium.

The sugar in sports drinks is intended to help replenish your glucose stores and sustain physical and mental performance. Sports drinks are only mildly sweet because if the carbohydrate concentration is too high, it will slow the rate at which the drink passes from your stomach to your small intestine, potentially triggering stomach upset. More than one type of sugar is often used in sports drinks, such as glucose and fructose, which don’t compete for absorption in the gut, so that combination ultimately may result in more carbohydrate being taken up and used by the body during exercise, which could improve performance. The sodium in sports drinks is intended to replace what’s lost in sweat, help preserve your thirst drive, support carbohydrate absorption in your gut, and help maintain fluid balance in the body. Although sweat also contains potassium, calcium, and magnesium, these minerals are lost in small amounts compared to sodium and typically are added only in small amounts to sports drinks, if at all.

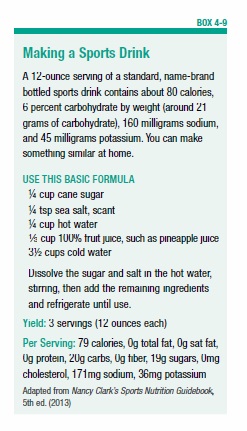

Because sports drinks are a little sweet and flavored, they can prompt drinking more readily than water might. However, sports drinks don’t come without downsides. Like other carbohydrate-containing beverages, such as fruit juice and soda, sports drinks can increase the risk of tooth enamel erosion and dental decay. To help protect your pearly whites, minimize the time the drink is in contact with your teeth. Use a squeeze-bottle to quickly direct the fluid to the back of your mouth, and avoid swishing the fluid around in your mouth. You also may want to consider making your own sports drinks, as the most common options on store shelves are laced with artificial flavors and colors, and many contain chemical preservatives (see Box 4-9, “Making a Sports Drink,” on page 43).

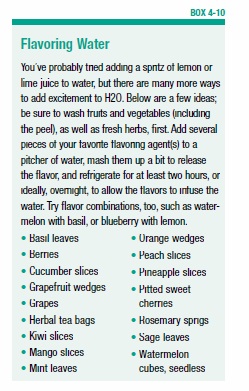

Although sports drinks are lower in calories than a soda, drinking them when you don’t really need to can contribute to weight gain. Some brands of sports drinks are available in lower calorie versions for those exercising at a lower intensity and/or duration, but this group of people could just substitute water. If plain water doesn’t excite you, there are plenty of ways to add flavor with minimal or no calories (see Box 4-10, “Flavoring Water”).

Sports drinks should not be confused with energy drinks, such as Red Bull, Monster, and Rockstar, which contain caffeine and sometimes other purported energy boosters such as guarana (which has twice the caffeine of coffee beans) and taurine (which boosts caffeine’s effects), not to mention sugar—more than 13 teaspoons in a 16-ounce can. These drinks are not designed to be fluid replacement beverages, and there is little scientific evidence to support the idea that such energy drinks improve sports performance. If they do seem to enhance performance, it would be difficult to determine whether the benefits are due to the drink formulation or just the caffeine (which can enhance endurance performance in some people), as this hasn’t been studied. There are plenty of reasons to avoid these drinks, though. Preliminary evidence shows energy drinks raise blood pressure in healthy adults compared to similar drinks formulated without caffeine and other stimulants. The acidic drinks also can harm teeth, and the stimulants may contribute to anxiety and sleep problems.

Caffeine and Water Loss

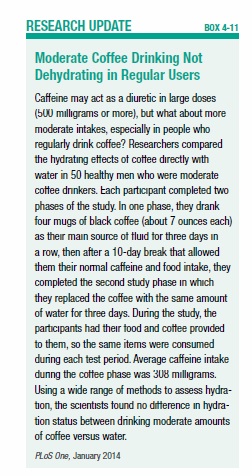

According to the American College of Sports Medicine, drinking caffeinated beverages has a modest diuretic effect (increases urination), but it does not interfere with hydration in people who habitually drink moderate amounts of caffeinated beverages, such as coffee, tea, and soda. (See Box 4-11, “Moderate Coffee Drinking Not Dehydrating in Regular Users,” on page 44). Regularly consuming caffeine may lead to tolerance against its diuretic effect. If you’re not used to drinking caffeinated beverages, they would not be a good choice before exercise, not only because of the possible diuretic effect, but also due to their potential to make you feel jittery.

Alcohol and Activity

It goes without saying that alcoholic beverages should be avoided right before exercise. Alcohol acts as a diuretic by inhibiting the production of a hormone that tells your body to hold onto water, thus contributing to dehydration. Alcohol also impairs judgment and balance, as well as slowing reflexes. It can suppress the use of body fat to fuel exercise, too. Excess drinking during the day prior to exercise may impair performance, even though blood alcohol concentration is zero. Additionally, the effects of alcohol on strength and performance may continue for several hours after signs of intoxication or hangover go away.

Although it may be tempting to celebrate with alcohol after an athletic competition such as a 5K run or a round of golf on a hot day, it could contribute to further water loss from the body, beyond exercise-related losses. Beverages with high alcohol concentrations, such as hard liquor, have a significant diuretic effect since they’re 30 to 50 percent alcohol, and they should not be used when you’re trying to rehydrate quickly. Wine, which is 15 to 20 percent alcohol, may be problematic as well. The alcohol concentrations in beer, 4 to 4.5 percent, may not interfere with hydration over the long-term in active people, but they aren’t a good choice when you’re trying to rehydrate quickly.

As a rule of thumb, avoid alcohol in the first few hours after activity. Besides interfering with rehydration, alcohol may interfere with post-exercise recovery by impairing storage of glucose and delaying muscle repair. Regardless of when alcohol is consumed, it also can decrease vitamin and mineral absorption, thus increasing risk of deficiency, and it can add unneeded empty calories, especially if consumed regularly.

The post 4. Hydration appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 4. Hydration »

Powered by WPeMatico