7. Living Brain-Healthy

The Benefits of Activity

We’ve seen how smart dietary choices can help protect your brain against age-related decline. But the truth is that the most important lifestyle changes you make for your brain happen between meals: To maximize your chances of maintaining peak brain power as you age, increase your level of physical activity. The evidence that physical activity—even just brisk walking, gardening, or household chores—contributes to cognitive health is even stronger than the associations between nutrition and cognition.

Get Going Now

The evidence also shows that the sooner you start being active, the better. Recently, the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study reported that the more physically fit you are when you’re younger, the more likely you are to keep your brain sharp as you age. Participants, originally ages 18 to 30, were tested for blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and other measures, and also walked at an increasingly fast pace on a treadmill until they couldn’t continue. The young adults could stick with the treadmill test an average of 10 minutes. Each additional minute that a participant had been able to last on the original treadmill measurement was associated with the equivalent of about one year’s less mental aging when they were given cognitive tests 25 years later.

But if you were a couch potato as a young adult, the study still had a glimmer of good news: The small group of participants who actually improved their fitness from the original treadmill testing scored better on the cognitive assessment than those whose fitness had declined or stayed the same.

In fact, other research has shown that even people already suffering from cognitive decline can benefit from becoming more physically active (see Box 7-1, “Activity Benefits Even Those with Cognitive Decline”).

Faster Is Better

Not surprisingly, more vigorous exercise is associated with greater benefits for your brain. The National Walkers’ Health Study, an analysis of data taken from almost 39,000 participants, found that a brisk pace has more benefits—even if the distance traveled is the same. Those reporting a pace slower than a 24-minute mile were at five-fold increased risk for mortality from dementia.

Picking up your pace even a little seemed to pay off, however: Those classified in the third-slowest category of walkers (about 15-17 minutes per mile) saw a significant reduction in their risk of dying prematurely compared to the slowest group. Looking specifically at dementia, each additional minute per mile in walking pace was associated with a 6.6 percent increased risk of mortality from Alzheimer’s.

Hippocampus Benefits

Taking a brisk walk might also help increase the size of the hippocampus, a key part of the inner brain involved in forming, storing, and processing memory. That’s the conclusion of a study using data from the Exercise for Cognition and Everyday Living (EXCEL) trial of 86 women, ages 70 to 80, already suffering mild cognitive impairment. One group of the women engaged in a twice-weekly aerobic walking program, designed to increase in intensity to 70 percent to 80 percent of each individual’s age-specific target heart rate. A second group was assigned to a resistance-training regimen, while a control group did only balance and stretching activities.

After six months, MRI scans found that those in the aerobics group saw a 5.6 percent increase in the left hippocampus, a 2.5 percent increase in the right hippocampus, and a 4 percent increase in total hippocampus volume. Those in the other groups did not see significant increases in hippocampal volume. Researchers noted that the increases in hippocampal volume among the walkers with MCI were double that observed in a previous study of cognitively healthy older adults—suggesting brisk walking might be of most benefit to those at greatest risk for dementia.

Some Is Better than None

Even if you can’t squeeze in a regular brisk walk or other activity, it’s better to get going when you can than to be completely sedentary. In another study, people who were consistently sedentary had the lowest levels of cognitive function at the beginning and suffered the fastest average rate of decline. Cognitive decline also was faster in those whose physical activity levels consistently dropped during the study period. People whose activity levels fluctuated still benefited from walking whenever they could, however. So even if you “fall off the activity wagon,” as researchers put it, you can get back on without losing a lot.

Genetic Risk

Exercise also may help protect people at higher genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers who used PET scans to image the brains of people identified as carriers of APOE epsilon-4, a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s, found that activity levels were inversely associated with amyloid plaque development in the brain. Among sedentary APOE epsilon-4 carriers, the scans showed greater buildup of the plaques associated with Alzheimer’s. But the carriers who were physically active, meeting the American Heart Association guidelines for regular exercise, showed no more buildup of amyloid plaques than found in the brains of non-carriers.

Measuring Activity

Most such studies, however, suffer from a reliance on participants’ self-reported activity levels. How can scientists be sure that subjects are really as active (or sedentary) as they say they are? Researchers at Rush University Medical Center sought to overcome that challenge using a wrist device called an actigraph. The device recorded movement of all kinds for 10 days at the start of the study to determine participants’ average activity levels. The 716 participants, average age 82, were initially free of cognitive impairment.

Over the next four years, 71 of the study group developed Alzheimer’s. Those in the bottom 10 percent of total physical activity were twice as likely to develop the disease as the most active 10 percent.

Smart Strength Training

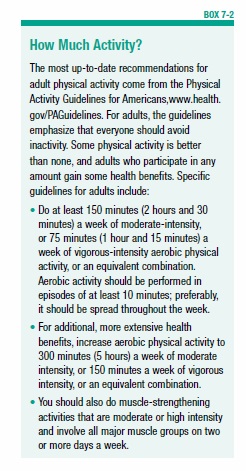

Along with aerobic activity such as brisk walking, it’s also important for older people to engage in strength training, such as lifting weights (see Box 7-2, “How Much Activity?”) To find out whether strength training is also good for the brain, University of British Columbia scientists conducted a six-month randomized trial of 86 women, ages 70-80, who suffered from mild cognitive impairment. Those assigned to resistance training using machines and free weights significantly improved their scores on memory tests. The study compared resistance training with aerobic exercise (an outdoor walking program) and a control group that did only balance and stretching activities. The aerobic group got fitter but saw no memory benefits.

In MRI scans of 22 participants, those in the weight-lifting group also saw significant functional changes in areas of the brain associated with cognition and memory, along with improving their test scores.

How Activity Benefits Your Brain

In chapter 1, we saw how recent discoveries have overturned former notions about the brain’s plasticity; it had been believed that age-related cognitive and brain changes were inevitable, and that the adult brain couldn’t grow new neurons. Now we know that even adults can increase their number of neurons and the connections between them. Not surprisingly, physical activity helps this process; it seems to be one of the ways in which activity benefits the brain.

A University of Illinois study showed that as little as three hours a week of brisk walking can boost the brain’s neurons. The research involved 59 healthy but sedentary volunteers, ages 60-79, who participated in a six-month randomized clinical trial. Half did aerobic exercises such as brisk walking, while a control group did only non-aerobic stretching and toning exercises. Researchers compared high-resolution MRI brain scans before and at the end of the exercise program. Those in the aerobic exercise group showed significant increases in brain volume, while those in the control group did not. The greatest gains from aerobic exercise were associated with the prefrontal and temporal cortices of the brain—areas responsible for memory and information processing that are especially prone to age-related deterioration.

Effects on Brain Atrophy and Shrinkage

Greater physical activity also seems to correlate with lower levels of brain atrophy and shrinkage. A University of Kansas study found that people with early Alzheimer’s disease who did best on a treadmill test were also less prone to the brain atrophy associated with the disease. The study used the treadmill to measure peak oxygen consumption—a gauge of cardiorespiratory fitness—along with MRI scans to view the brains of 57 patients with early Alzheimer’s and a control group of 64 people free of dementia. After controlling for age, higher peak oxygen consumption was associated with greater whole brain volume. People with early Alzheimer’s disease who were less physically fit had four times more brain shrinkage compared to normal older adults than people who were more physically fit.

Boosting Blood Flow

Much as physical activity can benefit cardiovascular health by improving circulation, it boosts blood flow in the brain. This may be another key to how being active benefits your brain. In particular, it makes sense that physical activity could reduce the risk for vascular dementia—the slow, progressive thief of memory and cognitive function associated with impaired blood circulation in the brain.

In an Italian study, regular, non-strenuous physical activity substantially reduced the risk of vascular dementia. Over a four-year span, participants who engaged the most regularly in moderate activity fared the best when it came to retaining cognitive function. Regular walking was associated with a 73 percent risk reduction for vascular dementia.

Other studies have shown that burning as little as an extra 100 daily calories can be enough to move you out of the highest-risk, most sedentary population (see Box 7-3, “Mission: Burn 100 Calories”).

Patients with cardiovascular health concerns, who can improve their heart health with physical activity, also seem to show brain benefits from exercise. In the Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study, for example, the equivalent of a daily, brisk, 30-minute walk was associated with lower risk of cognitive impairment. As activity levels increased, the rate of cognitive decline decreased. The study followed 2,809 women, average age about 73, who had either prevalent vascular disease or three or more coronary risk factors.

The Role of Sleep

As important as physical activity is to a healthy brain, so too is getting proper rest—especially a good night’s sleep. Findings from several studies suggest sleeping too little or too much, abnormal breathing during sleep, and excessive daytime sleepiness are significantly associated with cognitive impairment.

Researchers at the University of California at San Francisco studying a large group of veterans reported that those diagnosed with sleep disorders such as insomnia or apnea were 30 percent more likely to suffer dementia than those without sleep problems. When combined with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sleep disorders were associated with an 80 percent greater likelihood of dementia. The study looked at eight years of records on 200,000 veterans, most of them ages 55 and up. Scientists cautioned that more research is needed to determine whether disturbed sleep contributes to dementia; it could also be that dementia causes sleep abnormalities. But the findings do suggest that sleep problems may help identify those at increased risk for developing dementia.

Rx for Sleep: Seven Hours

Like Goldilocks, your brain seems to demand an amount of sleep that’s neither too little nor too much, but just right. That “just right” amount for most people seems to be about seven hours of sleep, give or take an hour or so.

Evidence for this comes from the large, long-running Nurses’ Health Study. Among the more than 15,000 participants, ages 70 and older, sleep quality was linked to cognitive health. After an initial cognitive examination, the women were followed for up to six years, including recording sleep duration and cognitive assessments. A subset of 468 women also had blood tests for the beta-amyloid compound associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Compared to the women who slept about seven hours per night, those who slept two hours more or less than seven hours performed worse on cognitive tests. Those sleeping five hours or less and nine hours or more also had beta-amyloid blood markers that predicted a greater risk of cognitive decline and dementia. Overall, abnormal sleep duration was cognitively equivalent to aging by two years.

In another long-term study, the French Three-City Study, excessive daytime sleepiness was associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline. The study followed nearly 4,900 non-demented participants, age 65 and older, for up to eight years.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, the implications of these findings about sleep could be substantial, as they may lead to the eventual identification of sleep-based strategies for reducing risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. Interventions to normalize sleep duration and correct sleep disorders have the potential to reduce or prevent cognitive decline.

The Effects of Stress

Exercise and eating right, as well as getting adequate sleep, also can help protect your brain by improving your defenses against stress. If you ever feel so stressed-out that your brain seems to skip—like the needle on a jiggled turntable—and you forget something important, it’s not just your imagination that stress may be to blame. Stress not only can make you feel older, but it actually can add to mental aging.

Stress Enzymes

Stressful situations over which a person feels he or she has no control have been found to activate an enzyme in the brain called protein kinase C (“PKC”). This enzyme affects the prefrontal cortex, which regulates thought, behavior, and emotion using operations often referred to as “working memory.” Too much PKC can impair your ability to concentrate, leading to distractibility, impaired judgment, impulsivity, and thought disorder.

That sense of events being beyond your control is key to the stress effect on the brain. Even mild stresses can activate the PKC that makes you easily distracted. The effect actually may have evolved as a protective mechanism in dangerous situations, when noticing every little sound in the woods and reacting on instinct could be lifesaving.

Cellular Aging

The effects of stress on the brain are not merely temporary. Chronic psychological stress also can speed up aging at the cellular level. Research has linked mental stress to high levels of oxidative stress—the process in which free radicals in the body damage DNA—and to low levels of an enzyme called telomerase, which helps rebuild aging cells. Compared to individuals with less stress, people under long-term psychological stress have shorter, shriveled telomeres.

Brain-Healthy Habits

Now that you know some of the important steps you can start taking today to protect your brainpower tomorrow, how can you put these healthy habits to work in your own life? “Most people know what they need to do to live healthier, but don’t do it,” says Tufts’ Sara C. Folta, PhD, who teaches the theory of behavioral change.

The key to adopting healthier habits and making them stick, Folta says, is to understand a model of behavior called dual-process. Your emotional, instinctive side is like an elephant, controlled (sometimes) by your cognitive, reflective, planning side—the “rider.” The elephant wants instant gratification, while the rider thinks long-term.

“The elephant wants what it wants, and wants it right now,” says Folta. “To change behavior, you have to enlist both the rider and the elephant, to get them both going in the same direction.”

Elephant Vs. Rider

Most healthy resolutions ultimately fail because your inner elephant can’t be directed for long by appeals to reason. “To motivate the elephant, you need a more emotional appeal,” Folta explains. You might try focusing on why you want to protect your brain: Picture yourself taking the vacation you’ve always dreamed of, or beaming proudly at your grandchild’s wedding.

Your “rider” can pose challenges, too. Particularly in areas like nutrition and health, it’s easy to get lost in a welter of information. In pursuing this fact and that study, the analytical rider might never get beyond planning and researching a brain-healthy diet to the point of actually eating better.

Set Specific Goals

It’s also important to set specific goals. A vague goal like “eat better” won’t suffice. “Eat five servings of fruits and vegetables a day” is better, if you’re clear on the definition of a “serving.” “Eat fish twice a week” and “eat red meat no more than twice a week” might be specific goals you can translate into action, though “eat fish every Tuesday and Friday” or “no red meat on weekdays” are clearer still. Black-and-white goals are best: “Make half your grains whole” might be too hard to put into daily practice. “No more white rice” and “buy only whole-grain pasta” are easier rules to follow.

How to Be Habit Forming

Habits can be good or bad, healthy or unhealthy for your brain. You might make a habit of taking a brisk walk every morning, but eating a doughnut every morning at 10 with your coffee break can be a habit, too.

There are three steps to what behavior experts call a “habit loop.” First comes the cue—whatever signal that triggers the habit (the clock shows 10, time for a break!). The cue leads to a routine, which could be physical, mental, or even emotional (grab that doughnut). Finally, the routine gives you a reward (the sweet, fatty richness of biting into a doughnut), which trains your brain—if the reward is good enough—to remember and repeat this loop.

Rethinking Rewards

To change unhealthy habits and establish healthy ones, you have to pay attention to the cues and the routines and substitute a different reward that doesn’t detract from your long-term goals. Maybe what you really crave at mid-morning isn’t a sweet treat so much as a distraction, or the company of others you meet at the doughnut stand. Could a 10 o’clock walk around the block with a few friends substitute for the reward in this routine?

Another strategy is to alter your environment in ways that promote more positive habits. For example, try putting a fruit bowl in a prominent spot in your kitchen. Says Folta, “Then you don’t have to think about choosing a piece of fruit to snack on. Your decision is pre-made.”

On the Right Track

Now that you know the latest state of the science in brain research and the effects of diet and lifestyle, you can start modifying your habits to match. It’s never too late to get started—research shows that even octogenarians’ brains benefit from smart dietary choices (see Box 7-4, “Less-Healthy Diets Linked to Poor Cognition After 85”).

These recommendations are not set in stone, however. Sometimes the public gets impatient with scientific research, especially when it comes to nutrition: Why can’t those scientists just make up their minds, once and for all? But that’s how science works—ever changing to adapt to new evidence. Keeping up with the latest findings can help you make the best decisions to protect your brain for the long term.

By doing everything you can for a healthy brain, in essence you are working to protect what makes you uniquely you. We’re confident that everyone who knows and loves you will agree that today is a good day to get started.

The post 7. Living Brain-Healthy appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 7. Living Brain-Healthy »

Powered by WPeMatico