5. Grains

Shift to Whole Grains

For better nutrition and reduced risk of chronic disease, shift your eating pattern to replace refined grains with whole grains. Adults who eat around 1,600 calories a day should get around five servings of grains daily, while adults targeting 2,200 calories a day may need around seven servings of grains—but at least half of daily grain servings should be whole grains (see Box 5-1, “What Counts as a Serving of Grains”). Unfortunately, Americans’ average intake of whole grains is far below recommendations, while our average intake of refined grains is too high. Almost half of the refined grains we eat are from mixed dishes, such as burgers, sandwiches, pizza, tacos, macaroni and cheese, and spaghetti with meatballs.

Whole grains are richer in nutrients than refined grains. Refining grains involves a process called milling, during which the nutrient-rich outer layers of grains are removed and a loss of vitamins (such as vitamin E and several B vitamins), minerals (such as iron and magnesium), fiber, and phytochemicals occurs. Although most refined grains are enriched with B vitamins and iron to replace what was lost during milling, the majority of the nutrients lost are not replaced.

A dietary pattern rich in whole grains has been linked to a reduced risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers (see Box 5-2, “Whole Grains Reduce Heart Attack Risk,” on page 39). Whole grains have been shown to have beneficial effects on inflammation, blood sugar levels, blood vessel function, and cholesterol levels. Whole grains, when eaten in place of refined grains, also may help you maintain a healthy weight. Observational studies suggest that eating too many refined grains, such as white bread and white rice, is just as likely to result in increased weight gain over time as eating sugar-sweetened foods.

Fitting in Whole Grains

Replace some of your refined grain choices with whole grains (see the next section for help identifying whole grains). Simply adding foods to your diet without eliminating others means you’re increasing your calories, which can result in weight gain. Additionally, some whole-grain foods may be high in added sugar and/or saturated fat, so consider the food’s overall nutritional value. For example, whole-grain muffins, although better than their counterparts made with refined (white) flour, may contain a lot of sugar and/or fat and should be eaten in moderation.

Although people are typically familiar with whole wheat, other whole grains, such as millet and spelt, are becoming more popular and more widely available. To help you understand your options, we’ve put together a chart (see Box 5-3, “Your Complete Guide to Whole Grains,” on page 40) that gives you an introduction to a variety of whole grains.

Buying, Cooking, and Storing Grains

- Learn to identify whole grains.

To evaluate the whole-grain content of foods, check the ingredient list and keep these points in mind:

- In all food ingredient lists, the first item on the list makes up the highest percentage of the product. Look for products with a whole grain listed as the first ingredient, or as the second ingredient if water is the first ingredient. If a food is made with several whole grains, look for them to appear near the beginning of the ingredients list. Ingredients that indicate whole grains include whole wheat, whole oats, and the word “whole” in front of any other grain. Whole-grain ingredients also include wheat berries, brown rice, oats, oatmeal, and sprouted grains (a refined grain can’t be sprouted).

- Many gluten-free grains are typically whole, even if they’re just listed as “millet,” “teff,” “quinoa,” or “amaranth.”

- The terms “enriched wheat” and “degerminated corn” indicate refined grains. Wheat, semolina wheat, and durum wheat are also likely to be refined grains unless they have the word “whole” in front of them. “Multi-grain” products don’t necessarily contain whole grains, so check the ingredients.

Another way to determine if a product contains a significant amount of whole grains is to look for the Whole Grain Stamp from the Whole Grains Council (see Box 5-4, “Whole Grain Stamps,” on page 41). If the product contains at least 8 grams of whole grains (half of a whole-grain serving), it may bear a Whole Grain Stamp. Food manufacturers have to pay a fee to participate in this program, so not all whole-grain products bear the stamp. The daily goal for whole grains is at least 48 grams, which is equivalent to three servings of whole grains. Learn more about the Whole Grain Stamp at wholegrainscouncil.org.

- Look for fiber.

Fiber is one component of whole grains that contributes to their health benefits. Women should aim for a daily fiber intake of at least 25 grams; men, 38 grams. Unfortunately, the average fiber intake of American adults is only about 15 grams per day.

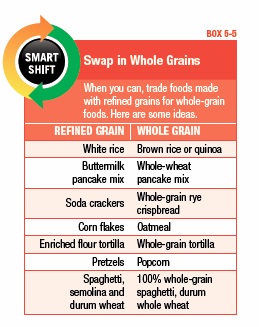

When choosing processed foods made with whole grains, checking fiber content using the 10-to-1 rule may help you make better grain choices. Look for whole-grain foods with at least 1 gram (g) of fiber for each 10 g of total carbohydrate. For example, if a whole-grain cereal has 22 g carbohydrate and 2 g fiber per serving and another one has 25 g carbohydrate and 5 g fiber per serving, the latter is likely the better choice. This doesn’t mean you should automatically dismiss a whole-grain food if it’s lower in fiber. For example, ½ cup of cooked brown rice has 18 g carbohydrate and 1 g fiber, but it’s still a more nutritious choice than refined white rice. For more ideas to increase your intake of fiber and whole-grain foods, see Box 5-5, “Swap in Whole Grains.”

- Try sprouted grains.

Sprouted grains and sprouted flours—which are both inherently whole grain—are made by allowing whole grains to germinate under carefully controlled conditions so they’re just barely sprouted, then drying the grains. The sprouting process may increase levels of some vitamins and minerals, such as vitamin E and zinc, and/or their availability to the body. Sprouted grains such as brown rice, oats, barley, and quinoa can be eaten as cereals and side dishes or used in soups. Some sprouted grains, such as wheat and corn, are ground into flour you can buy, which you can use in baking recipes much like you’d use regular whole-grain flour.

- Cook intact whole grains in batches.

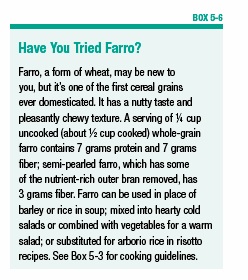

Intact whole grains—ones that haven’t been ground into flour or flaked, such as oat groats and farro (see Box 5-6, “Have You Tried Farro?”)—take longer to cook, so it’s a smart strategy to cook extra portions and refrigerate or freeze them for later use. Toss leftover whole grains, such as wheat berries or quinoa, into soups, stews, and casseroles, or use them as a base for salads, pilafs, or cereal breakfasts flavored with fruit and spices. Intact whole grains are digested more slowly and generally have a gentler effect on blood sugar levels.

- Store whole grains properly.

Whole grains naturally contain oils that can eventually become rancid. To deter rancidity, store whole grains in airtight containers in a cool, dry place away from direct light for up to two months. Or, store tightly wrapped whole grains in the refrigerator or freezer for up to a year.

The post 5. Grains appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 5. Grains »

Powered by WPeMatico