5. Asthma

Asthma is a chronic disease that often starts in childhood but can occur for the first time in adulthood, even later in life. In the United States, about 19 million adults and seven million children have asthma.

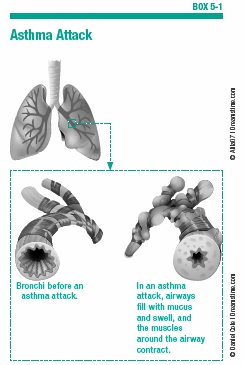

People with asthma have inflammation in their airways. This inflammation causes episodes of coughing, wheezing, breathlessness, and chest tightness. The inflammation also causes the airways to secrete excess mucus, which clogs the airway, restricting the flow of air. In addition, the muscles surrounding the airways sometimes suddenly contract, causing the airway to narrow (see Box 5-1, “Asthma Attack”).

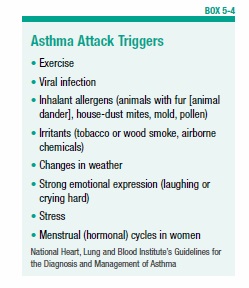

Asthma attacks usually occur in response to a specific trigger, such as pollen, house-dust mites, animal dander, or mold, all of which can also cause allergies. One study found that about 75 percent of 20 to 40 year olds with asthma and 65 percent of adults aged 55 and older with asthma have at least one allergy. Exposure to cold air, exercise, a viral infection, airborne irritants (chemicals, tobacco, or wood smoke), stress, or strong emotions can also spark an asthma attack.

For most people with asthma, the airway narrowing is reversible. The airway will return to normal either spontaneously, or with the aid of a bronchodilator drug (see page 24). In some people with more severe asthma, the constant inflammation causes permanent changes to the airways. For these people, the condition may not be completely reversible even with medication. It is often very difficult or impossible to distinguish this form of asthma from COPD.

Asthma is on the increase among children younger than 18, and it is more common in boys than girls. Women are more prone to adult-onset asthma than men, and more adult women than adult men have asthma. It can first appear in older age. The diagnosis of asthma in older adults may be missed because other health problems with similar symptoms (such as heart disease or COPD) may coexist.

What Causes Asthma?

The exact cause of asthma is not fully known, but it is believed to result from a combination of genetic and environmental factors. In other words, some people inherit genes that make them susceptible to developing asthma. Numerous genes have been identified that appear to play some role in asthma. In people with these genes, some type of exposure to environmental factors during a crucial time in their development alters their immune system in a way that leads to chronic inflammation in the airways and sensitivity to certain stimuli. This leads to asthma attacks.

Immunity Gone Awry

Inflammation is part of the normal protective response of the body’s immune system. The highly complex immune system defends the body against harmful substances (such as bacteria, viruses, and irritants) that can enter through any opening (such as the mouth, the nostrils, or a wound). The immune system generates inflammation for a variety of reasons, including to serve as a barrier against the spread of infection, and to promote healing.

Normally, inflammation subsides once the harmful invader has been eliminated. But sometimes inflammation becomes chronic and can be problematic, as happens in people with asthma.

The immune system is not static. It continuously responds and evolves based on what the body encounters from the external environment, which can include bacteria, viruses, and pollutants, among others. It also responds to internal factors, such as stress.

Environmental Factors

One theory is that for asthma to develop, very specific combinations of genes and environmental factors must be present. Environmental exposures that have been most clearly linked to the development of asthma are airborne allergens and viral respiratory infections (such as pneumonia, a cold, or flu). One study found that children who had a lung infection such as pneumonia before age three had nearly double the risk for asthma or wheezing later on.

Other factors that may also be associated with the development of asthma include:

Smoking

One study suggests that cigarette smoking may raise the risk for developing asthma. In addition, cigarette smoking during pregnancy has been linked to a greater risk for the child to experience bouts of wheezing, although it is not certain that this leads to asthma.

Air Pollution (Particularly High Ozone Levels)

Some research suggests that young children exposed to traffic-related pollution are more likely to develop respiratory problems such as wheezing (which is a symptom of asthma). Some evidence suggests that babies born to women exposed to air pollution during pregnancy may be at greater risk for asthma.

Obesity

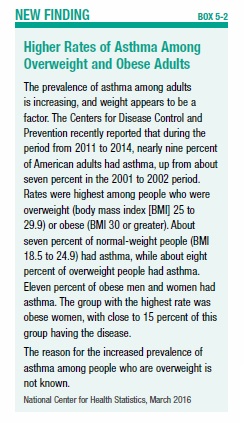

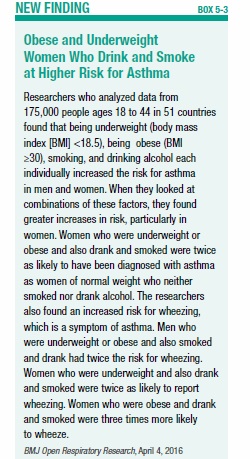

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently reported that more overweight and obese adults have asthma than adults of normal weight. The highest rates of asthma are among obese women (see Box 5-2, “Higher Rates of Asthma Among Overweight and Obese Adults,” on page 46). Another study found that underweight women also have an increased risk for asthma, and that both obese and underweight women who drink and smoke have twice the risk for asthma compared with women of normal weight who don’t drink or smoke (see Box 5-3, “Obese and Underweight Women Who Drink and Smoke at Higher Risk for Asthma”). The reasons for these links are not known.

Stress

Several studies have found that children who suffer adversity, such as physical abuse, the death of a parent, divorced or separated parents, or living with someone who has a drug or alcohol problem, mental illness, or has served time in jail are at increased risk of developing asthma. The reason for this association is not known, but it is possible that childhood adversity causes chronic stress, which can have detrimental effects that lead to asthma.

Mold Exposure

A few studies have found that infants who live in homes with mold are more likely to develop asthma than those not exposed to mold.

Anemia

One study found that the children of women who had anemia during pregnancy are at increased risk for asthma.

Birth Country

Simply being born in the U.S. appears to increase the risk for asthma. Children and teenagers who are born in other countries and immigrate to the U.S. are about half as likely to have asthma and allergies as children born in the U.S., according to one study. The reason for this is not known.

Environmental Protection

Some studies have found that certain environmental exposures and conditions appear to have a protective effect against asthma. For example, in rural farming communities, where children are exposed to more microbes than children in cities or suburbs, there is a lower incidence of asthma.

Two studies found that breastfeeding may help to protect children from asthma, but the reason for a potential link between breastfeeding and better lung function is not known. The World Health Organization recommends breastfeeding exclusively for the first six months of life.

Symptoms of Asthma

The most common symptom of asthma is a cough, although wheezing (a high-pitched whistling sound, especially when exhaling), chest tightness, and shortness of breath also are common.

In people with asthma, respiratory symptoms worsen in response to particular stimuli. The symptoms may occur, and often seem to worsen, at night. In some people, especially young children, the only symptom of asthma will be a cough that is worse at night.

An asthma attack may occur suddenly or may begin slowly, with gradually worsening symptoms. It may be over quickly, or can last for several hours. In some cases, an initial asthma attack will ease up and then be followed by a second, possibly more severe, attack. Some severe asthma attacks will cause significant difficulty breathing, and the lips and fingernails may turn grayish or bluish from lack of oxygen (a condition known as cyanosis). In the event of a severe asthma attack, it may be necessary to go to a hospital emergency room or a physician’s office for immediate treatment.

Research suggests that people who are obese (a body mass index greater than 30) may experience worse asthma symptoms than those of normal weight, due to dynamic hyperinflation. This means that air that is breathed in gets trapped in the lungs and is not exhaled, and the result is a greater feeling of breathlessness.

Diagnosing Asthma

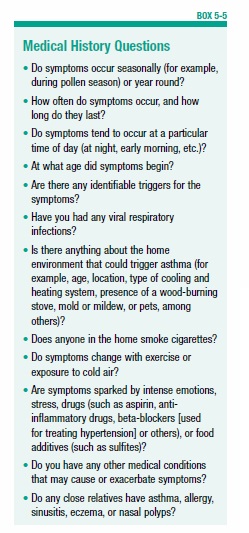

A physician will suspect asthma in a person who has characteristic symptoms that recur, and are triggered by or worsened by certain stimuli (see Box 5-4, “Asthma Attack Triggers”). To make the diagnosis, the physician will take a detailed medical history, conduct a physical examination (including listening to the chest for wheezing sounds), and perform a spirometry test (see page 19). This often involves bronchodilator reversibility testing (see page 19) to determine if the airflow obstruction is reversible, which is typical in asthma. The spirometry test also may be used to rule out other possible causes of symptoms, such as COPD. While taking a medical history, the physician is likely to ask the questions in Box 5-5, “Medical History Questions.”

Treatment for Asthma

Asthma can’t be cured, but it can be effectively managed by preventing asthma attacks as much as possible, and treating them when they occur. According to the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) “Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma,” the goals of asthma treatment are to reduce the intensity and frequency of asthma attacks, and to prevent any adverse effects of asthma (such as the need for hospitalization), as well as any side effects of asthma medications. Ideally, if asthma is well managed:

- There will be few bothersome symptoms. This means that symptoms will occur in the daytime no more than twice each week, and symptoms in the night will be limited to no more than twice each month.

- Use of an inhaled bronchodilator will be needed only two or fewer times per week.

- Normal daily activities, such as work, school attendance, exercise, and participation in athletics, will not be hindered.

- Air flow, as measured with a peak flow meter (see page 19), will be normal.

- The need for hospitalization or use of oral steroids for asthma symptoms will occur no more than once per year.

Achieving these goals involves eliminating or minimizing asthma triggers, and using appropriate drug therapy (usually inhaled beta-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids). For people with asthma that is triggered by allergies, immunotherapy (commonly known as allergy shots) may be used. Everyone with asthma should follow the recommended schedule for influenza and pneumonia vaccinations (see pages 65 and 72).

Avoid Asthma Triggers

All people with asthma should try to identify the substances or circumstances that trigger asthma attacks, and then do everything possible to avoid, limit, or manage exposure to them. There are many possible asthma triggers, and people with asthma are unlikely to be bothered by all of them. Therefore, it is important to take some time to figure out what is likely to set off an attack, and then take steps to avoid it. Here are some strategies:

Pollen and Mold

Outdoor allergens include pollen and mold. Allergy season varies depending on where you live. In many parts of the U.S., allergy season begins in early spring, as trees and shrubs begin to leaf out and flowers start to bloom. In early March, common allergies come from tree pollen. In late April and early May, grass begins to pollinate. Allergies from pollinating plants can continue through July. In August, ragweed and other weeds can cause allergies. In warmer southern states, the allergy season can last longer than in the north.

To limit exposure to pollen and outdoor mold during allergy season, keep windows closed as much as possible and try to stay indoors around midday, when pollen and some mold spore counts are highest. It may be necessary to increase the dose of medication just before and during allergy season if you are sensitive to pollen and outdoor mold.

Indoor mold can grow wherever there is dampness or wetness. To keep the house as dry as possible, make sure faucets, pipes, and other sources of water are not leaking (fix them if necessary). Clean any surfaces that have mold. Basements, which can be damp, should be dehumidified if possible.

Pet Allergies

For people who have an allergic response to cats, dogs, or other animals with fur, it is the animals’ flakes of skin (dander) or dried saliva that cause the reaction. The best option for people with asthma that is triggered by animal dander is not to have a pet. For those who value the companionship of an animal and do not wish to deprive themselves of pet ownership, some precautions may help. If possible, keep the pet outdoors—if this is not possible, keep the pet out of the bedroom. Remove carpets, which can attract animal hair, dander, and dried saliva, or keep the pet out of carpeted rooms.

Insects

Some people with asthma are allergic to the dried droppings and remains of cockroaches. Even crumbs can be a food source for cockroaches, so do not leave any food out (keep all food and garbage in closed containers). Cockroaches like warm hiding places and water, so do what you can to limit possible hiding places and water sources (for example, fix plumbing leaks). Use poison baits, powders, gels, or pastes to kill cockroaches if you see them.

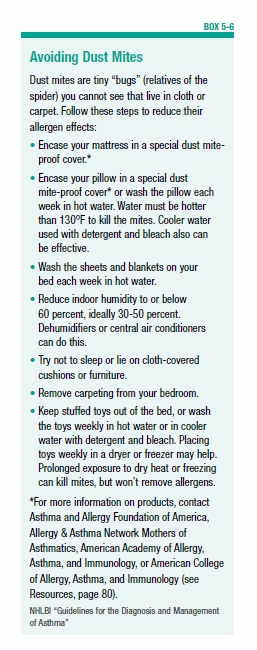

Dust mites are microscopic bugs that can live in carpets, furniture, mattresses, and bedding. Dust mites are harmless to humans, but they can trigger allergies and asthma attacks. Some strategies for avoiding dust mites are in Box 5-6, “Avoiding Dust Mites.”

Smoke, Strong Odors, and Sprays

Smoke from cigarettes, cigars, pipes, or a wood-burning stove or fireplace can be an asthma trigger for some people. It is best to stay away from people who are smoking, and to keep the home smoke-free. A person with asthma who smokes should quit (see page 36) and should encourage other people living in the home who smoke to stop as well. Smoking increases the risk for numerous diseases, including cancer and heart disease, as well as COPD.

Strong odors and sprays, such as perfume, hair spray, talcum powder, paint, new carpet, and others can also be problematic for some people with asthma. Exposure to these irritants should be limited as much as possible. In addition, air pollution can trigger an attack.

Exercise

To minimize the chance of experiencing symptoms while exercising or engaging in sports, be sure to spend about 10 minutes warming up before engaging in vigorous exercise. Check the air quality and pollen levels if you are allergic to pollen, and try to exercise during times when air quality is good and pollen levels are low.

Medications

Some people with asthma are sensitive to certain medications. Drugs that can trigger asthma symptoms include beta-blockers (used to treat high blood pressure), aspirin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs are used for pain relief and include common over-the-counter drugs such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and naproxen (Aleve). Aspirin and NSAIDs trigger asthma symptoms in about three to five percent of adults with asthma.

For people who are bothered by any of these medications there are alternatives, both for treating high blood pressure (for those sensitive to beta-blockers) and for pain relief (for aspirin or NSAID sensitivity). Your physician will make specific recommendations.

Sulfites in Foods

Some foods and drinks contain sulfite compounds. These compounds work as a preservative to prevent discoloration, and can be found in beer, wine, processed potatoes, dried fruit, sauerkraut, and shrimp. About five percent of people with asthma have a worsening of symptoms when they eat foods containing sulfites. The only remedy for these individuals is to avoid any sulfite-containing foods. Foods and beverages that contain sulfites must indicate this on the label.

Drug Therapy for Asthma

In addition to avoiding asthma triggers, most people with asthma will need drug therapy. There are two general types of drug therapy for asthma: long-term control medication, and quick relief medication. Long-term control medications are taken daily to prevent symptoms. These are generally anti-inflammatory drugs (see page 25), which work over time to reduce inflammation, maintain lung function, and prevent asthma from worsening. Quick relief medications, usually bronchodilators (see page 24), are used to open airways promptly during an asthma attack or just before exposure to a known trigger.

Many of the bronchodilator and anti-inflammatory drugs used for asthma are the same ones used to treat COPD (see “Drugs to Treat Obstructive Airway Diseases,” page 23). But they are used differently for two conditions.

Other drugs that might be used for asthma include leukotriene receptor antagonists such as montelukast (Singulair) and zafirlukast (Accolate), theophylline (Theolair, Uniphyl), cromolyn sodium (Intal), and nedocromil (Tilade). People with severe asthma may be treated with one of an increasing number of specialized drugs called monoclonal antibodies, which target the cells causing inflammation. These drugs include omalizumab (Xolair), mepolizumab (Nucala), and reslizumab (Cinqair).

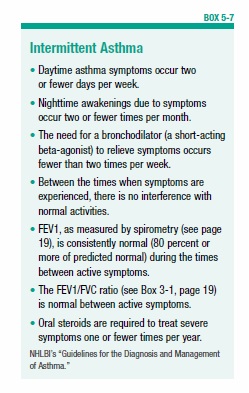

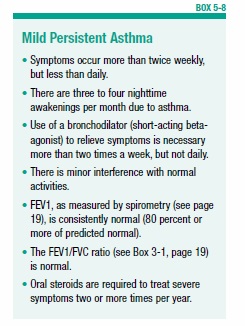

The exact medications and frequency of use for asthma will depend largely on the severity of the disease. Asthma is classified as intermittent or persistent, and persistent asthma is further classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

Intermittent Asthma

People with intermittent asthma (see Box 5-7, “Intermittent Asthma”) generally will be treated only with a quick relief medication. In most cases, this will be a bronchodilator, specifically a short-acting inhaled beta-agonist (see page 24), such as albuterol (VoSpire ER), levalbuterol (Xopenex HFA), or pirbuterol (Maxair Autoinhaler). This medication is taken on an as-needed basis for immediate relief when symptoms arise. People with asthma who experience symptoms during exercise may be instructed to use a short-acting inhaled beta-agonist about 10 minutes before exercise to prevent symptoms.

If a bronchodilator is needed on more than two days a week, it may signal that asthma is worsening or not under good control. If this happens, asthma may be classified as persistent, and a change in treatment may be warranted.

Mild Persistent Asthma

For people with persistent asthma, daily treatment with a long-term controller-type medication is used. For those with mild persistent asthma (see Box 5-8, “Mild Persistent Asthma”), this will most likely be a low dose of an inhaled corticosteroid (see page 25). In addition, a short-acting beta-agonist will be used for immediate symptom relief.

Other options for long-term controller medications in people with mild persistent asthma are leukotriene receptor antagonists (montelukast, zafirlukast), theophylline, cromolyn sodium, or nedocromil.

The two leukotriene receptor antagonists, montelukast and zafirlukast, are taken in pill form rather than inhaled. Leukotrienes are chemicals that are part of the body’s natural immune system. Along with a substance called histamine, they cause inflammation in response to a perceived invader. In people with allergies and asthma, the body mistakenly perceives harmless substances, such as pollen (and other allergens), as a threat. Exposure to allergens sparks leukotrienes to produce inflammation. Montelukast and zafirlukast work by blocking the action of leukotrienes, thereby preventing inflammation.

Cromolyn sodium and nedocromil, which are inhaled, are in a drug class called mast cell stabilizers. Mast cells are part of the body’s immune system. In the presence of a foreign invader, mast cells break down and release large amounts of histamine, which contributes to the production of inflammation. Cromolyn sodium and nedocromil work by preventing mast cells from breaking down. This stops histamine from being released, and prevents inflammation.

Moderate Persistent Asthma

For moderate persistent asthma (see Box 5-9, “Moderate Persistent Asthma”), there are two options for long-term controller therapy:

- A medium dose of an inhaled corticosteroid (see page 25), or

- A low dose of an inhaled corticosteroid, plus a long-acting inhaled beta-agonist (see page 24).

If a long-acting inhaled beta-agonist is used, it should not be used as the only medication and it should be used for the shortest possible time. Long-acting beta-agonists include salmeterol (Serevent), formoterol (Foradil), and arformoterol (Brovana). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued the following statement regarding the use of long-acting beta-agonists to treat asthma. These drugs should:

- Only be used in combination with an asthma controller medication, such as an inhaled corticosteroid.

- Be used for the shortest time possible to bring asthma symptoms under control, and then discontinued.

- Only be used long-term in patients for whom asthma control can not be achieved with other drugs.

- Be used by children and adolescents only in the form of combination drugs that contain both a long-acting beta-agonist and a corticosteroid.

In making its decision, the FDA cited studies showing an increased risk of severe worsening of asthma symptoms, leading to hospitalization in some children and adults, and even death in some patients. Some studies have indicated that using an inhaled corticosteroid in combination with a long-acting beta-agonist abolishes the risk, but this has not been proven and continues to be studied. The warning does not apply to people with COPD.

The two most commonly used long-acting beta-agonists are salmeterol and formoterol. Four drugs that combine a long-acting beta-agonist with an inhaled corticosteroid are salmeterol plus fluticasone (Advair), formoterol plus budesonide (Symbicort), formoterol plus mometasone (Dulera), and vilanterol plus fluticasone (Breo Ellipta).

Alternatively, for moderate persistent asthma, a leukotriene modifier or theophylline may be given with a low dose of an inhaled corticosteroid. In any case, a short-acting beta-agonist will continue to be used for immediate symptom relief.

Severe Persistent Asthma

Severe persistent asthma (see Box 5-10, “Severe Persistent Asthma”) is treated with a medium-to-high dose of an inhaled corticosteroid (see page 25) combined with a long-acting inhaled beta-agonist (see page 24). Just as with moderate persistent asthma, use of a long-acting beta-agonist without an inhaled corticosteroid is not recommended.

If this does not adequately control asthma symptoms, the drug omalizumab (Xolair) or one of two new drugs—mepolizumab (Nucala) and reslizumab (Cinqair)—may be used. Omalizumab reduces the body’s sensitivity to allergens, and is used only for people who have moderate to severe asthma that is triggered by allergies. It is given by injection every two to four weeks. Mepolizumab and reslizumab reduce levels of cells called eosinophils, which play a role in allergic reactions and contribute to inflammation. These drugs are given by injection every four weeks. They are used only in combination with other asthma medications.

People with severe asthma that cannot be controlled with any of these therapies may be given oral corticosteroids. This generally is recommended only for short periods of time due to the potential side effects of taking corticosteroids in pill form rather than inhaled.

Recommendations for All Asthma Patients

Ongoing medical care for all people with asthma is recommended. Once a treatment plan has been initiated, people with asthma should visit their healthcare professional every one to six months (depending on the severity of the asthma) to ensure that treatment is working and that the treatment goals are met.

For all people taking medications for asthma it is important to understand the difference between long-term control medications and quick-relief medications.

➧ Long-term control medications must be taken daily. They prevent symptoms, often by reducing inflammation. They will not provide quick relief for symptoms.

➧ Quick-relief medications, which work by relaxing airway muscles, promptly relieve symptoms. These medications are not effective for long-term control of asthma.

For the most part, long-term control medications should keep asthma symptoms under control, with only occasional need for quick relief. If quick-relief medications are needed on more than two days each week, this is an indication that a change in long-term control medication may be needed.

One study found that 49 percent of asthma patients were not using needed controller medication. Of the 51 percent of asthma sufferers who were using controller medications, only 14 percent had adequate control of their asthma. People with poor asthma control were at higher risk for emergency department visits and hospitalizations. Another study found that children with poorly controlled asthma had lower-quality schoolwork and more sleep problems than children with well-controlled asthma.

Improving control of asthma symptoms has clear benefits for both children and adults. The challenge is how to accomplish this. People with moderate-to-severe asthma must set aside time from busy lives to take control medication every day. It is easy to forget: One study found that people with asthma who received reminders to use their control inhalers were more likely to consistently use them than those who did not receive the reminders. A variety of smartphone and tablet applications are available to help people remember to take medications, keep track of symptoms, and communicate with their physician.

An intriguing study showed that getting adequate amounts of vitamin D may be important for people with asthma. The study found that people with asthma who had very low vitamin D levels (below 30 ng/ml) in their blood had almost twice the amount of hyper-responsiveness (indicating an increased tendency for bronchospasm) than those with higher levels. Those with high levels of vitamin D had better lung function, and a better response to drug therapy with inhaled corticosteroids.

Another study found that taking vitamin D supplements did not reduce the rate of asthma exacerbations in adults with persistent asthma and low vitamin D levels. It remains to be seen whether measuring vitamin D levels and treating with vitamin D will become a standard treatment for asthma.

It has long been suspected that gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)—in which acid backs up from the stomach into the esophagus, causing heartburn and other symptoms—interferes with asthma control. Therefore, some doctors have recommended treating children who have asthma with heartburn drugs even if they do not have heartburn or other symptoms of GERD. Newer research shows that for children with asthma and nonsymptomatic GERD, adding a heartburn drug to their asthma medications did not help, and slightly increased the risk of sore throats and other respiratory problems.

The severity of asthma can change over time, either for better or worse. Therefore, treatment may need to be adjusted either to improve control of the disease or, if it is well controlled, to attempt to reduce medications (to minimize the risk for side effects).

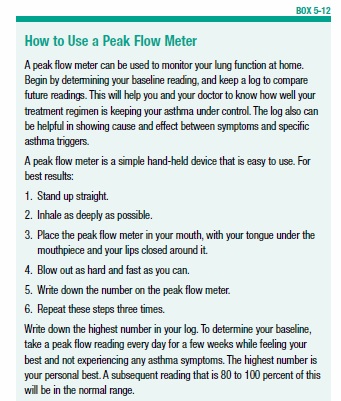

At home, people with asthma should take an active role in managing and monitoring their condition by using medications as prescribed, keeping track of the frequency and intensity of symptoms, identifying triggers, and recognizing early signs that asthma may be worsening (see Box 5-11, “The Asthma Patient’s Role in Disease Management”). Adults and children age five and older with moderate to severe asthma may be instructed in how to use a peak flow meter to keep track of their lung function (see Box 5-12, “How to Use A Peak Flow Meter”). At visits to the physician’s office, spirometry will often be used to test lung function.

Immunotherapy

If asthma symptoms are clearly triggered by identifiable allergens, a type of therapy called immunotherapy may be recommended. Immunotherapy (sometimes called allergy shots) involves repeated injections of small amounts of the allergen (the substance triggering the reaction) in an attempt to desensitize the person to the substance. Immunotherapy is most effective in people who have a reaction to a single allergen, particularly dust mites, animal dander, or pollen.

Allergy shots can be given to children over five years old and adults of all ages, even older adults. A recent study that tested allergy shots in adults ages 65 to 75 found them to be both safe and effective (see Box 5-13, “Allergy Shots Effective for Older Adults”).

Traditional allergy immunotherapy is called subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT). Before immunotherapy is begun, skin tests will be performed to clearly identify the allergen. First, allergy shots, which are given subcutaneously (under the skin), will be given once or twice a week for about four to six months. For the next four to six months, the shots will be given every two to four weeks. This therapy will generally continue for several years. Eventually the body becomes less sensitive to the allergen, reducing the chance of asthma attacks.

In rare cases, a severe and potentially life-threatening reaction called anaphylaxis can occur as a result of the shots. For this reason, it is important that the shots be administered in a physician’s office that is equipped with the facilities and trained personnel to treat this type of reaction.

For people with grass or ragweed allergies who don’t like shots, there is another option. With sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT), small tablets are placed under the tongue, where they dissolve and are absorbed into the body. This immunotherapy option is taken once a day. It must be started three to four months before exposure to the allergic substance. For a person with a pollen allergy, this means starting to use the sublingual tablets well in advance of pollen season, which will depend on your geographic location.

Three sublingual treatments are available: Grastek (for grass pollen allergies), Oralair (for grass pollen allergies), and Ragwitek (for ragweed allergies).

Like with the allergy shots, a severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) can occur. Therefore, the first dose of the sublingual tablets will be taken in the doctor’s office.

The post 5. Asthma appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 5. Asthma »

Powered by WPeMatico