Cochlear Implants May Help You Hear Better

Nearly 25 percent of U.S. adults ages 65 to 74 and 50 percent of those age 75 and older have disabling hearing loss, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. While it can be irritating not to be able to clearly hear the television or keep up with a conversation without missing words here and there, hearing loss comes with more serious side effects. “It is a risk factor for social isolation, depression, and dementia, and is associated with a greater risk for falls,” confirms Enrique R. Perez, MD, assistant professor of otolaryngology at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai.

Age “Muffles” Hearing The inner ear is lined with microscopic hair cells that pick up sound waves and transform them into electrical impulses that travel along the auditory nerve to the brain, which interprets them as speech, the doorbell, your dog barking, and so on. As you age, these tiny cells gradually die off or are damaged, making the ear less responsive to sound waves. Exposure to loud noise over many years hastens this process, and poor cardiovascular health also can be a factor, since it impedes blood flow to the inner ear. “Certain medications—for example, some chemotherapy drugs, and strong antibiotics—also can directly injure the inner ear, leading to hearing loss,” Dr. Perez adds.

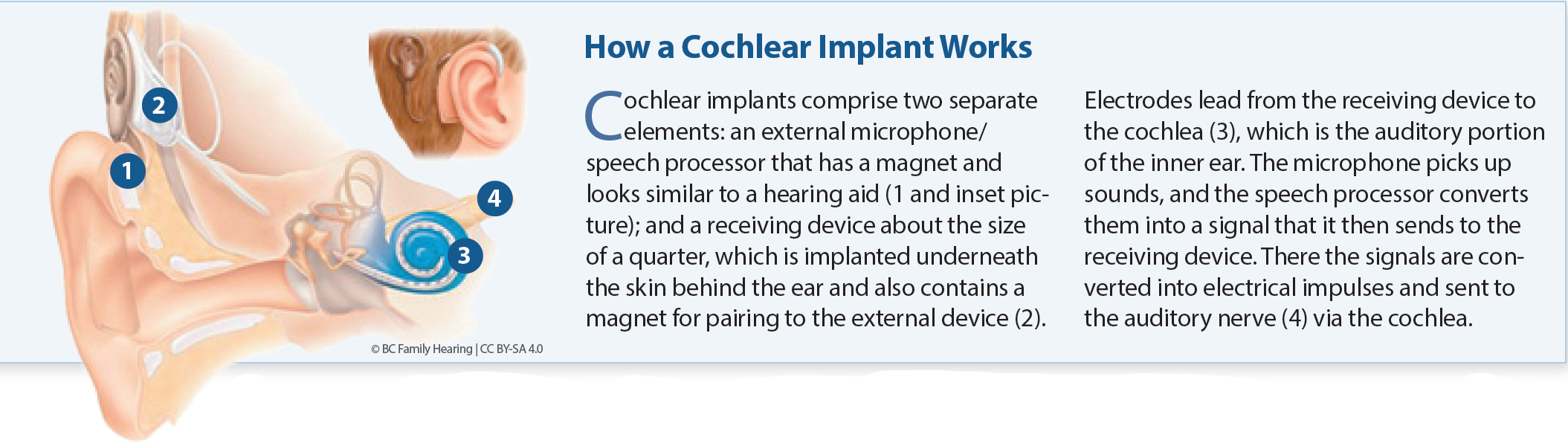

Bypassing the Ear Many people with mild to moderate hearing loss find that personal sound amplifiers and/or hearing aids make a big difference to the problem. But those whose hearing loss is so severe that even amplified speech is difficult to understand may benefit from cochlear implants. Unlike hearing aids, which amplify sound, cochlear implants bypass damaged structures in the ear and transmit sound information directly to the auditory nerve that signals the brain (see How a Cochlear Implant Works).

Research has suggested that cochlear implants improve symptoms of depression, and boost cognitive function. A recent study (JAMA Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, Jan. 7) points to the gains in speech recognition for people receiving implants. The study included 470 participants, average age 61, most of whom were active users of hearing aids prior to cochlear implantation. Their hearing was evaluated using standard tests six and 12 months after the implantation procedure. The analysis showed significant benefits for most participants, with 262 people having an 85 percent improvement in word recognition, 226 having an 87 percent improvement in sentence recognition, and 33 having a 79 percent improvement in sentence recognition with background noise.

Are You an Implant Candidate? You won’t be denied cochlear implantation on the basis of your age, but you do need to be healthy enough for general anesthesia (the surgery takes about two hours). You also must have a cochlea that is structurally suitable for implantation, and a healthy auditory nerve.

Cochlear implants are covered by Medicare for people who have severe or profound hearing loss in both ears (defined as recognizing fewer than 40 percent of the words in a sentence test carried out in a quiet room while wearing hearing aids). Medicare coverage also depends on you being willing to participate in a rehabilitation program after implantation. “Everyday sounds, including speech, will sound different from what you remember with natural hearing,” Dr. Perez says. “Rehabilitation focuses on training your brain to recognize and interpret the sounds.”

Some Risks Involved For most people, cochlear implantation is straightforward, but there are some risks associated with the procedure. “These include bleeding and infection at the surgery site, and some implant recipients also have reported facial nerve weakness, and balance problems after the surgery,” Dr. Perez says. ‘Rarely, cochlear implants worsen tinnitus: ‘phantom’ sounds that are heard even though there is no external source for the sounds.”

It’s important to keep in mind that not everybody who undergoes cochlear implantation benefits. In the study we reference, a small number of participants had equivalent preoperative and postoperative hearing scores—moreover, four participants had worse speech recognition after cochlear implantation. It also is possible that people who still have residual hearing will lose this after implantation. These are important factors to consider, particularly if you are at the upper limits of implant candidacy while wearing hearing aids. “It isn’t easy to gauge how much a person may benefit from cochlear implants prior to surgery,” Dr. Perez says. “This means that people with residual hearing have to balance the known benefit they derive from hearing aids with the unknown benefit they may gain from cochlear implants. Moreover, it’s possible that continuing advances in hearing aid technology could make a difference to your hearing in the future, but you would need to still have that residual hearing to benefit.” That said, Dr. Perez notes that advances in implant design and surgical techniques are now making it possible to preserve residual hearing in some people who still have a degree of functional hearing but struggle to understand speech with hearing aids only. “Simultaneous implant and hearing aid use in selected individuals may yield an even better outcome than a cochlear implant alone,” he adds. Be sure to have a full and frank discussion with your doctor before making the decision to proceed with cochlear implantation so you are fully aware of the possible benefits and drawbacks, and have realistic expectations for the outcomes.

Traditional Hearing Aids Traditional hearing aids work in a different way from cochlear implants, magnifying sound vibrations entering the ear so that surviving hair cells can pick them up. Aids come in several different designs, some more visible and some small enough to be worn inside the ear, out of sight. But while hearing aids are the mainstay for alleviating hearing loss in seniors, research suggests that only about one in five people who would benefit from hearing aids actually use them. Cost is likely a factor—one hearing aid costs up to $4,000 (which may include the audiology consultation and evaluation, fitting, and follow-up appointments to adjust the hearing aid as necessary). Traditional Medicare doesn’t cover the cost of hearing aids or exams for fitting them, although some Medicare Advantage plans do.

Hearing aid affordability will likely be improved by a new category of over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids people will soon be able to purchase directly without needing to consult a health professional. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration was expected to issue guidance on the sale of OTC hearing aids in 2020, but the process was delayed by the covid-19 pandemic. “Once approved, OTC hearing aids will likely be most suitable for people with mild to moderate hearing loss,” Dr. Perez says. “However, people with more profound impairment may find that these aids don’t adequately amplify sounds.”

Do You Need Help to Hear Better? Signs that your hearing may not be what it was include having to ask family members and friends to repeat themselves, being unable to follow conversations (particularly in noisy surroundings), and having to turn up the volume on the television or radio. If you’re experiencing any of these symptoms, ask your doctor to refer you to an audiologist who can thoroughly evaluate you for hearing loss.

The post Cochlear Implants May Help You Hear Better appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: Cochlear Implants May Help You Hear Better »