6. Treatment: Taking the Right Medications

Heart failure lasts a lifetime, but it can be treated for a lifetime by making sensible lifestyle decisions outlined in Chapter 5, with medical procedures described in Chapter 7, and with the medications discussed here.

Some of those drugs improve the ability of your heart to pump blood efficiently. Others are designed to prevent fluid buildup. Still others dilate blood vessels, making it easier for the heart to do its job, or control its rhythm. And certain combinations of medications manage your symptoms and make you feel better. You may be one of those patients who need multiple medications, and the more you know about what you are being asked to take,

the better.

To get the most benefit possible from heart failure drugs, you have to take them exactly as prescribed by your doctor. Correct and continuing use of medications, says the American Heart Association, saves lives, prolongs life, and improves the heart’s function.

The sooner you get started on a program of medications, the more effective they are likely to be. A 2017 study of more than 14,000 patients published in Advances in Therapy found that those who had been treated with national guideline-recommended medications within one month of diagnosis had the lowest two-year mortality rate.

A 2018 study found that permanent lung damage caused by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which frequently exists with heart failure, starts even before patients show symptoms. With that information, doctors can recommend earlier intervention with medications and other therapies.

Questions to Ask

Talk with your doctor, pharmacist, or other health-care provider about all the drugs you take. Know each drug’s purpose and possible side effects. If you don’t fully understand, ask questions, even if instructions are given on the container’s label.

- What is the name of the medication?

- What is it supposed to do?

- What are the most common side effects?

- How often should I take it?

- Should I take it on an empty stomach?

- Should I take it at the same time every day?

- Should I avoid certain foods or alcohol?

- What if I forget to take my medication?

Medications

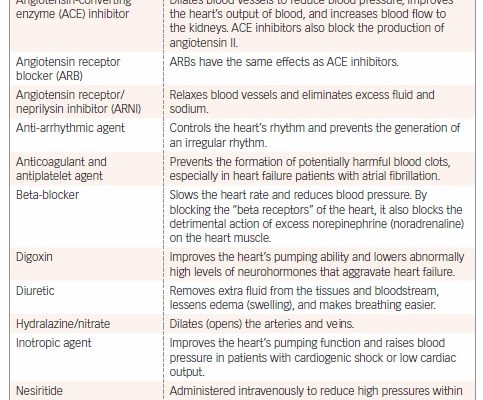

More than a dozen medications have been proven to be beneficial for heart failure patients. See “Medications Commonly Used in the Treatment of Heart Failure” for a quick review. For more detailed information, read the sections below, starting with one of the most frequently prescribed heart failure drugs—ACE inhibitors.

ACE Inhibitors

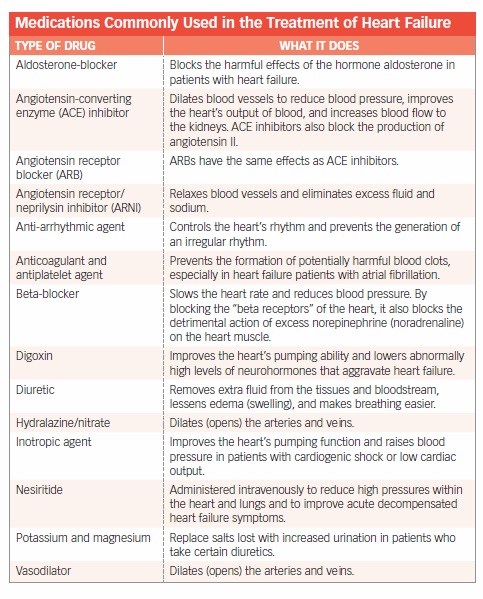

ACE inhibitors are a major contributor in the improved prognosis for heart failure patients who receive treatment early in the course of the condition. “ACE inhibitors Used in Heart Failure” lists six specific drugs, initial dose, target dose, and frequency.

They work by dilating blood vessels, which allows blood to flow more easily. When the kidneys release renin, a series of reactions takes place that ultimately generate a hormone called angiotensin II, which constricts small arteries and raises blood pressure. ACE inhibitors block the key enzyme in this process. When angiotensin II production drops, arteries relax and dilate, and blood pressure drops.

ACE inhibitors decrease the incidence of sudden death, heart attack, and stroke. They improve quality of life by relieving symptoms, and they enhance blood flow to the kidneys. ACE inhibitors also increase exercise tolerance and prevent—sometimes reverse—ventricular remodeling.

AHA and ACC guidelines recommend ACE inhibitors for anyone at increased risk of heart failure due to hypertension, diabetes, or atherosclerosis. Those guidelines also call for ACE inhibitor use in all patients with evidence of structural heart disease and in patients with the most severe heart failure.

People with high potassium levels, a history of angioedema (swelling of the face and throat), and some patients with impaired kidney function should not take ACE inhibitors.

Side Effects. The maximum benefit of ACE inhibitors is seen at the recommended doses. However, therapy is usually started at a lower dose to reduce side effects. Once a dose is well tolerated, it is increased, and the process is repeated. It may take up to three months to get the full benefit of an

ACE inhibitor.

A common side effect of ACE inhibitors is a dry, hacking cough. Although it can be annoying, most people will tolerate some coughing in exchange for the drug’s proven benefits. Because heart failure itself can cause a cough, the ACE inhibitor is not always to blame. Nevertheless, if the cough is annoying, switching to an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) may be appropriate.

Other possible side effects of ACE inhibitors include dizziness and an abnormal sense of taste. If ACE inhibitors make you dizzy, avoid caffeine, alcohol, and overeating. A small number of people are allergic to ACE inhibitors and may experience swelling of the face or other parts of the body (angioedema).

ARBs

ARBs (like ACE inhibitors) also interfere with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. However, instead of blocking the formation of angiotensin II—as ACE inhibitors do—they block the effect of angiotensin II on organs and tissues. ARBs typically do not cause a cough.

Two ARBs—valsartan (Diovan) and candesartan (Atacand)—have been approved by the FDA for use in patients with heart failure. Several other ARBs are commonly used in heart failure, although they are not FDA-approved for this purpose. The most popular one is losartan (Cozaar). ARBs are primarily useful for systolic heart failure.

If you have heart failure with a low ejection fraction and cannot tolerate ACE inhibitors, taking candesartan in addition to other heart failure medications is better than not taking an ARB. In fact, the combination of an ARB (candesartan) and an ACE inhibitor has been shown to provide additional protection from death and hospitalization.

Side Effects. ARBs are generally well tolerated but can cause dizziness, headache, and cough, although the latter is much less likely than with ACE inhibitors. Most physicians start heart failure patients on a diuretic plus an ACE inhibitor and only switch to an ARB if the ACE inhibitor is not tolerated.

ARNIs

Cardiologists consider a class of drugs called angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) to be one of the most exciting developments in heart failure in decades. These drugs relax blood vessels and eliminate excess fluid and sodium in an entirely new way.

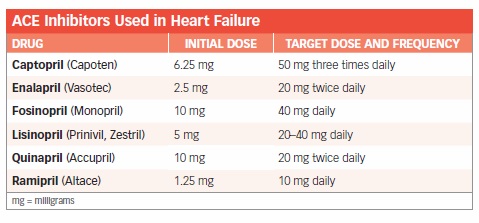

In clinical trials, the first drug in this class, sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) showed dramatic ability to reduce deaths and hospitalizations in patients with heart failure. Its benefits were so striking that the FDA expedited approval of the drug. It has since been shown to boost patients’ ability to live a normal life (see “Chronic Heart Failure Drug Successfully Treats Acute Heart Failure”).

ARNIs are now recommended as a replacement for ACE inhibitors and ARBs in patients with stage II and III heart failure (as classified by the New York Heart Association) and an ejection fraction of less than 35 percent to further lower hospitalizations and mortality.

Side Effects. ARNIs should not be taken with ACE inhibitors or ARBs. If you switch to an ARNI from either of these drugs, you will likely need a period of about 36 hours between stopping the old drug and taking the ARNI. Possible side effects from ARNIs include low blood pressure (hypotension), elevated potassium levels, dizziness, and cough.

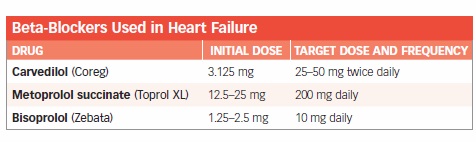

Beta-Blockers

Beta-blockers control the activity of the sympathetic nervous system that produces norepinephrine. The sympathetic nervous system activates what is known as the “fight or flight response.” Norepinephrine is a chemical released in response to stress. Because the release of norepinephrine affects other organs of the body, it also is referred to as a stress hormone.

People with heart failure and high levels of norepinephrine in their blood have an increased risk of dying from their condition.

In several major clinical trials, adding beta-blockers to other heart failure drugs improved survival by 34 percent. Overwhelmingly positive data has prompted guidelines calling for the addition of beta-blockers to the standard treatment of diuretics and ACE inhibitors for heart-failure patients.

In addition to increasing survival, beta-blockers slow the progression of heart failure, improve NYHA functional class, and reduce the risk of hospitalization and arrhythmias. They also may prevent many of the harmful effects of ventricular remodeling by increasing the ejection fraction and decreasing the size of the heart. These biologic effects appear to reverse remodeling. Beta-blockers also lessen the symptoms of heart failure and make patients feel better.

ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines recommend beta-blockers for patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction but no symptoms, and patients with stable NYHA class II-IV heart failure. They are also recommended for all patients who have had heart failure.

The Joint Commission, an independent body that accredits and certifies health-care organizations, requires that heart failure patients be given a prescription for beta-blockers when they are discharged from the hospital.

Side effects. Finding the proper dose of a beta-blocker is extremely important because the drug can slow the heart rate or lower blood pressure, further limiting the heart’s ability to pump efficiently. Different beta-blockers come in a variety of strengths and are taken once or twice a day. The dose of these beta-blockers may be doubled every two weeks until the maximum tolerated dose is reached.

The most common side effects of beta-blockers are dizziness, slow heartbeat (bradycardia), shortness of breath, and fatigue. These effects usually can be managed by adjusting the dose. It’s important that you never adjust the dose on your own. Other side effects may include cold hands and feet, headache, nightmares, difficulty sleeping, wheezing, difficulty breathing, skin rash, swelling of the feet and legs, and sudden weight gain.

Patients with acutely decompensated heart failure—a sudden worsening of heart failure symptoms—should not use beta-blockers. Patients with very severe diabetes, asthma, or peripheral vascular disease may not be able to tolerate beta-blockers. An experienced heart failure specialist may decide to use beta-blockers in these situations, but you will need to be carefully monitored.

The use of ivabradine (Corlanor) has been approved by the FDA for symptomatic heart failure patients who cannot take beta-blockers or tolerate the recommended doses. Ivabradine slows the heart rate like beta-blockers do, enabling it to pump more effectively.

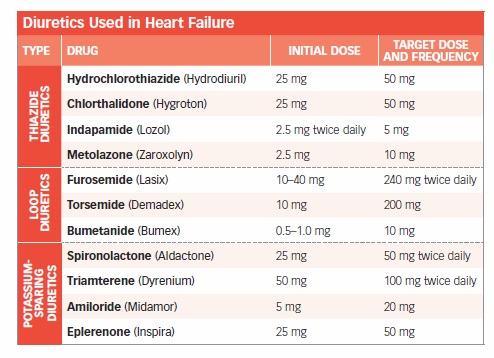

Diuretics

Diuretics cause the kidneys to excrete more water and sodium. They eliminate excess fluid and decrease swelling.

The three main types of diuretics are thiazide, loop, and potassium-sparing. They work differently to achieve the same effect. Thiazide diuretics are most commonly used to treat high blood pressure, while the more powerful loop diuretics often are used in kidney and heart failure. Potassium-sparing diuretics are weaker and are typically combined with thiazide or loop diuretics to prevent the potassium loss that occurs with diuretic use.

Cardiologists prescribe diuretics for approximately 90 percent of patients and strive to use the lowest effective dose. You may be allowed to adjust your own diuretics based on your symptoms, following specific instructions from your doctor. You will monitor your weight daily, and if you gain more than three pounds above your normal baseline weight, you may increase the diuretic dose as instructed.

Some people with mild or moderate heart failure who take an ACE inhibitor and beta-blocker do not need a daily diuretic. However, as heart failure becomes more severe, diuretic requirements increase. Not complying with your sodium and fluid restrictions also will lead to greater fluid retention and a heavier reliance on diuretics.

Side Effects. The diuretic your doctor prescribes will depend on your individual situation. The vast majority of heart failure patients are started on a loop diuretic, such as furosemide (Lasix), bumetanide (Bumex), or torsemide (Demadex). Those who need a stronger diuretic effect may require a combination of loop and thiazide diuretics.

Spironolactone (Aldactone) is a potassium-sparing diuretic and neurohormonal modulator that improves survival in patients with severe heart failure when added to therapy with an ACE inhibitor, beta-blocker, digoxin, and diuretics.

Diuretic doses are based on the severity of heart failure, as well as on diet, salt and fluid intake, activity level, and kidney function. Doses are adjusted as needed to relieve swelling and congestion. High doses can cause fluid and electrolyte imbalances from loss of sodium and water. Loss of too much sodium can cause low blood pressure, dehydration, and worsening kidney function.

Overly Aggressive Use. Overly aggressive use of diuretics also can cause imbalances in other minerals and electrolytes in the body, including potassium, magnesium, calcium, and chloride. Elderly or debilitated patients are more susceptible to these adverse effects than younger patients.

Patients with acute decompensated heart failure require large doses of diuretics delivered intravenously to drain the extra fluid from their bodies. However, they often stop responding to conventional diuretics. Ularitide, a synthetic natriuretic peptide, was developed as an alternative treatment for this patient population. The TRUE AHF trial showed the drug relieved congestion and patients felt better within 48 hours.

If you take diuretics, it is important to keep your blood potassium level normal to prevent an abnormal heart rhythm from occurring. Potassium-sparing diuretics raise blood potassium levels. Thiazide and loop diuretics lower blood potassium levels. Either way, severe potassium imbalances produce the same symptoms: weakness, numbness, confusion, and heaviness in the legs.

If you take a thiazide or a loop diuretic and are not on a potassium-sparing diuretic, it is important to eat potassium-rich foods, such as baked potatoes, dried fruit, bananas, white beans, cantaloupe, and spinach. You also may need a potassium supplement. However, never take a potassium supplement or a salt substitute containing potassium unless instructed by your doctor, no matter which type of diuretic you are taking.

Sunburn, Rash. A few people who use diuretics find they sunburn more easily, and some may get a rash. Another common effect of diuretic use is dry mouth. If this happens to you, use sugar-free hard candy to stimulate the flow of saliva. People who take diuretics are more susceptible to attacks of gout, a type of arthritis that causes painful joint inflammation.

Diuretics also may cause nausea, confusion, drowsiness, weakness (due to low blood pressure), and muscle or leg cramps. If you experience any of these side effects, tell your doctor.

Digoxin

Digoxin is in a class of drugs known as cardiac glycosides and helps the weakened heart contract more strongly by inhibiting an enzyme called adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) in heart cells. More importantly, digoxin inhibits ATPase in the kidneys and the central nervous system, which decreases neurohormonal activation. For this reason, digoxin is classified as a neurohormonal modulating agent.

Digoxin improves symptoms, functional capacity, exercise tolerance, and quality of life in patients with heart failure. It also can reduce hospitalizations for worsening heart failure, particularly in patients with an ejection fraction of less than 25 percent. Digoxin does not improve survival.

Side Effects. Digoxin is available as tablets (Lanoxin, Digitek), a pediatric elixir (Lanoxin Pediatric), liquid-filled capsules (Lanoxicaps), or a liquid used for injection (Lanoxin Injection).

Oral digoxin is usually taken once daily on a regular schedule. A low dose—0.125 milligrams (mg)—is effective in most patients. Lower doses are used in frail elderly patients and patients with kidney dysfunction. Occasionally, higher doses may be used in patients with arrhythmias. Doctors consider the patient’s weight, kidney function, age, cardiac medications, and the presence of other diseases when choosing a dose. High doses can be toxic.

To maintain a digoxin level less than 1.0 mg per milliliter (ml), regular monitoring is needed. When the dosage of digoxin is optimal, side effects are uncommon. At higher doses, side effects may include cardiac arrhythmias, gastrointestinal problems, such as nausea and vomiting, and neurologic problems, such as vision changes, headache, fatigue, and confusion. If you experience such side effects, contact your doctor immediately.

Certain drugs can decrease the effect of digoxin or increase its concentration to a potentially dangerous level. If you are taking antacids, kaolin-pectin (Kaopectate), Milk of Magnesia, or the anti-rheumatic drug sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), allow as much time as possible between taking these drugs and digoxin.

When digoxin is taken with certain drugs—including clarithromycin (Biaxin), erythromycin (Erythrocin), amiodarone (Cordarone, Pacerone), itraconazole (Onmel, Sporanox), cyclosporine (Neoral, Restasis), or verapamil (Calan)—the digoxin dose must be reduced.

Withdrawal from digoxin can result in a worsening of symptoms, so most heart failure patients must take the drug as long as symptoms persist.

Aldosterone Antagonists

Aldosterone is a hormone secreted by the adrenal glands. Its main function is to signal the kidneys to retain sodium and water. Spironolactone (Aldactone) and eplerenone (Inspra) are weak diuretics that also block the hormone aldosterone from interacting with its receptor.

Aldosterone antagonists are prescribed primarily to help patients eliminate excess water, but they have the ability to reverse left-ventricular remodeling and improve survival in people with heart failure.

The starting dose of spironolactone for severe heart failure symptoms is usually 12.5 to 25 mg per day. Patients with kidney dysfunction should not take the drug. Kidney function and potassium levels must be monitored regularly in all patients taking spironolactone.

Eplerenone is approved for the prevention of heart failure following a heart attack in patients with a history of heart failure or an ejection fraction of 40 percent or less. A major study demonstrated that eplerenone reduced deaths and hospitalizations in people who had experienced a recent heart attack and had evidence of heart failure or low ejection fraction.

Side Effects. Aldosterone is a steroid hormone and a mineralocorticoid. Other steroid hormones regulate sugar metabolism (glucocorticoids) and sexual characteristics (estrogens and androgens) by interacting with their own receptors. Because steroid hormones share certain molecular characteristics, aldosterone also can interact with receptors for glucocorticoids, estrogens, and androgens. This is why spironolactone can cause gynecomastia (breast enlargement in men). Because eplerenone blocks only the mineralocorticoid aldosterone receptor, it does not cause gynecomastia.

Patients with impaired kidney function should not take aldosterone antagonists due to the increased risk for elevated potassium levels.

Hydralazine Plus a Nitrate

Nitrates release nitric oxide, which dilates arteries and veins. Hydralazine causes small arteries to dilate and independently lowers blood pressure. It also appears to preserve nitrates’ effectiveness, which can wane over time. Together, the two drugs improve blood flow, lower blood pressure, and relieve symptoms. The drug combination reverses remodeling and improves the heart’s performance.

The combination of hydralazine plus a nitrate (Imdur, Isodil, Nitro-Patch) may be primary therapy for heart failure in African American patients. It also is approved as an add-on therapy for any patient who continues to experience the symptoms of NYHA class III heart failure while taking ACE inhibitors, digoxin, beta-blockers, and spironolactone.

The combination also may be useful in patients whose kidneys do not function well or who develop elevated potassium levels and cannot tolerate ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

Side Effects. Hydralazine may cause flushing, headaches, loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, watery eyes, nasal congestion, and a rash. Report these side effects to your doctor if they persist.

More severe side effects include joint or muscle pain, tingling in the hands and feet, swollen ankles and feet, a rapid heartbeat, chest pain, and fever. If you experience these symptoms while you are taking hydralazine, you should call your doctor immediately.

Intravenous Vasodilators

Conventional intravenous vasodilators include nesiritide (Natrecor), nitroglycerin (Nitrostat), and nitroprusside (Nitropress). These medications are used to dilate arteries and veins in critically ill heart failure patients.

Nesiritide is used at the physician’s discretion. Intravenous nitroglycerin is generally started in the hospital emergency department and continued in the intensive care unit. An oral form of the drug may be given for use after discharge. Nitroprusside is used in patients with severe heart failure to improve symptoms, relieve congestion, lower blood pressure, and increase cardiac output.

When this powerful arterial and venous dilator is used, patients must be carefully monitored to avoid hypotension (low blood pressure). Nitroprusside is rarely used outside the intensive care unit.

Side Effects. Possible side effects include flushing, rash, itching, hives, nausea, and vomiting, blurred vision, and difficulty breathing or swallowing. Report these symptoms to your doctor immediately.

Intravenous Inotropes

Intravenous inotropes include dobutamine and milrinone. They are used in critically ill heart failure patients with shock, low blood pressure or low cardiac output. Intravenous inotropes also are given to patients awaiting heart transplantation and are used as continuous palliative therapy to improve quality of life for end-stage heart failure patients who wish to remain at home.

Intravenous inotropes are not recommended for the routine treatment of acute decompensated heart failure, due to lack of long-term benefit and increased risk of complications such as low blood pressure, arrhythmias, and death. Intermittent infusions of these agents are discouraged as no clinical trials have shown benefit.

Side Effects. Headaches and nausea are possible. More serious side effects, such as a slow or rapid heartbeat, chest pain, and difficulty breathing, should be reported to your doctor immediately.

Other Drugs

Other drugs may be used in heart failure patients who have abnormal heart rhythms, low levels of certain electrolytes, and/or high cholesterol levels.

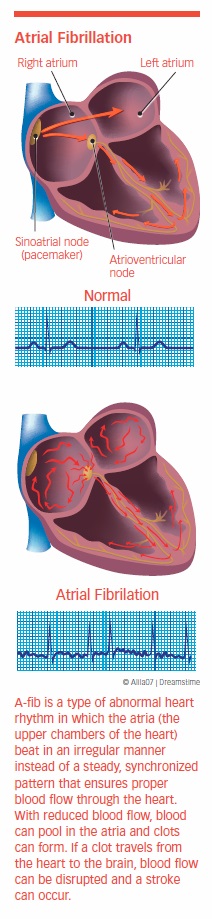

Anti-Arrhythmia Medications

People with heart failure can develop one of two heart rhythm abnormalities: supraventricular arrhythmia or ventricular arrhythmia. The most common supraventricular arrhythmia is atrial fibrillation (A-fib), which occurs in up to 30 percent of people with heart failure. A-fib causes the atrial muscle cells to contract in a rapid, disorganized manner. This prevents the heart from filling properly, and cardiac output can drop by as much as 20 percent from the loss of normal rhythm. A-fib also increases the risk of a blood clot (thrombus), which can cause a stroke, peripheral embolism, or pulmonary embolism.

A-fib may resolve on its own, although it often requires the use of drugs or other treatment. When A-fib continues to occur, antiarrhythmic drugs, such as amiodarone, or a technique called ablation, may be used to stop it. In most studies comparing medications to ablation, ablation was more successful at helping patients remain alive, active, arrhythmia-free, and out of the hospital. However, a recent study called the Catheter Ablation vs. Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy in Atrial Fibrillation or “CABANA” trial demonstrated that ablation was not superior to drug therapy for the primary cardiovascular outcomes of death, disabling stroke, serious bleeding, or cardiac arrest at five years among patients with new onset or untreated A-fib that required therapy.

Ventricular arrhythmias, such as ventricular fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia, are known to increase the risk of sudden death. Unfortunately, efforts to suppress these arrhythmias with drug therapy have been disappointing. Surgically implanted defibrillators that monitor heart rhythm often are needed. These do a better job than anti-arrhythmia medications at preventing sudden death.

Supplements

One risk of diuretic therapy is low potassium and/or magnesium levels, which increases the likelihood of dying from an arrhythmia. Fortunately, these conditions are easily corrected with potassium or magnesium supplements. Low potassium is less likely to occur in patients taking ACE inhibitors and spironolactone or eplerenone. In fact, high levels of potassium can occur with aldosterone-blockers. Patients taking potassium supplements may need to stop or reduce their supplements when starting an aldosterone-blocker.

Statins

Statins lower cholesterol and, in the process, reduce heart attacks and death in patients with elevated cholesterol. They also have other beneficial effects, including the ability to reduce inflammatory factors and cytokines, improve endothelial function, and stabilize plaque.

While statins have demonstrated a beneficial effect in ischemic heart disease, the data on statins and heart failure have been more controversial. The two large-scale randomized trials looking at statins and heart failure failed to find a long-term benefit, although several observational studies have shown improved outcomes. There is little data that statins reduce the risk of death in systolic heart failure patients who do not have elevated cholesterol, coronary artery disease, or diabetes.

The data for diastolic heart failure patients, on the other hand, are more compelling. A large observational study of Medicare patients demonstrated that one- and three-year mortality rates were lower among diastolic heart failure patients who were taking statins, regardless of their age, total cholesterol level, or the presence of coronary artery disease, diabetes, or hypertension, than in patients taking the traditional ACE inhibitor or beta-blocker therapies.

A more recent study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association in March 2018 found that higher-intensity statin use (Fluvastatin, atorvastatin, pitavastatin, or rosuvastatin) was associated with lower all-cause death and heart failure hospitalization in patients with diastolic heart failure and coronary artery disease.

In terms of preventing heart failure hospitalizations, the longer statins are taken, the greater the benefit. In studies, the impact of statins on heart failure complications appeared after five years of use. After 15 years, the drugs reduced heart failure hospitalizations by a whopping 43 percent.

The use of statins in heart failure appears to be most beneficial in the early stages of the disease. Studies have failed to show a benefit by adding statins in later stages.

Drugs with Promise

A drug with potential is sildenafil (Viagra, Revatio). Sildenafil offers a number of benefits in heart failure with pulmonary hypertension. Specifically, it allows patients to breathe better, and in one study, it also reduced hospitalizations for heart failure. The drug also appears to limit heart remodeling, in effect slowing the deterioration process that is the hallmark of heart failure.

Vasopressin antagonists (“aquaretics”) have the potential to remove fluid and decrease congestion without adversely affecting blood pressure, heart rate, electrolyte levels, or kidney function. In other words, they tend to do the work of diuretics without upsetting the body chemistry.

Although the vasopressin antagonist tolvaptan (Samsca) failed to improve survival in clinical trials, the drug was approved for short-term treatment of hyponatremia (low sodium levels). Use of this drug is limited, however, by its high cost and its potential to cause damage requiring liver transplantation or resulting in death.

Avoid These Drugs

Some medications are detrimental to people with heart failure and should either be stopped or used with great caution. They include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), anti-arrhythmia drugs, and drugs that treat diabetes.

NSAIDs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs include ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn). If it is necessary for you to take NSAIDs, your cardiologist will want to monitor you closely.

Anti-Arrhythmia Medications

Many anti-arrhythmia drugs are contraindicated for people with heart failure. However, a new procedure—pulmonary vein ablation—has proven effective in eradicating A-fib and can eliminate the need for anti-arrhythmia drugs. This invasive procedure is performed by an electrophysiologist (a cardiologist who specializes in heart-rhythm disorders).

Diabetes Medications

Diabetes medications in the thiazolidinedione class, such as pioglitazone (Actos), may increase tissue swelling in patients with heart failure. Some physicians have not found the risk to be excessive and feel the advantages of this drug may outweigh the risks. If you have heart failure and are taking this medication, your doctor may not stop the drug but may instead monitor your case closely.

The FDA has warned of an increased risk of heart failure in patients taking saxagliptin (Onglyza) and alogliptin (Nesina). The risk was particularly worrisome in patients with existing cardiovascular or kidney disease. The warning was extended to patients taking combinations that contain the two agents: saxagliptin plus metformin extended release (Kombiglyze XR), alogliptin plus metformin (Kazano), and alogliptin plus pioglitazone (Oseni).

Saxagliptin and alogliptin are dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors. A large trial conducted with sitagliptin (Januvia), a third member of the same class of drugs, found no increased risk for heart failure in type 2 diabetes patients. Nevertheless, the AHA listed both sitagliptin and saxagliptin, but not alogliptin, in their updated list of drugs that may cause or exacerbate heart failure.

If you need diabetes medication, discuss treatment options with your physician. If you are taking a DPP-4 inhibitor and develop heart failure, your doctor should discontinue that drug immediately. Recently, another class of drugs called DPP-2 inhibitors has been associated with increased risk for heart failure. Until the true risk is understood, doctors will be prescribing these drugs on a case-by-case basis.

Some diabetes drugs are safe for heart failure patients. GLP-1 drugs, which include exenatide (Byetta) and liraglutide (Victoza), may lower the likelihood of needing hospitalization for heart failure by 41 percent and the risk of death from any cause by 80 percent. Metformin (Glucophase) is showing promise in some studies.

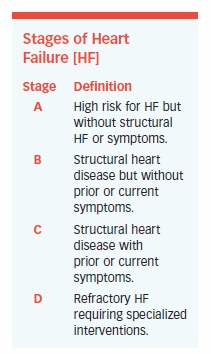

Treatment by Classification

The ACC and the (AHA) classify heart failure by four stages, all based on possible structural damage to the heart and prior or current symptoms. Lifestyle changes, medical procedures, and medications are recommended or prescribed according to the stage of heart failure.

Stage A. Patients are considered at high risk of developing heart failure but don’t have symptoms. Treatment focuses on eliminating risk factors through lifestyle modifications, such as weight loss, exercise, and avoidance of tobacco, illicit drugs, and excessive alcohol. Patients with diabetes and/or confirmed coronary artery disease should be prescribed ACE inhibitors or ARBs, statins (cholesterol-lowering drugs), and/or low-dose aspirin.

Stage B. Patients have no apparent symptoms of heart failure, but have confirmed structural heart disease. Many have had a heart attack, others have cardiomyopathy or valve disease. In addition to the lifestyle modifications and medications listed for stage A, most patients should take an ACE inhibitor or ARB, and a beta-blocker. An implantable cardioverter defibrillator may be advised in patients with a low ejection fraction.

Stage C. Patients have structural heart disease and symptoms of heart failure, such as shortness of breath, fatigue, and reduced exercise tolerance. In addition to all measures appropriate for stages A and B, these individuals should restrict salt intake, use a diuretic, and take an ACE inhibitor or an ARB, plus a beta-blocker. In some, digoxin may be recommended. An aldosterone antagonist may be prescribed for left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and mild-to-severe heart failure symptoms or after a heart attack.

Surgical intervention could be considered in select patients. An ICD is recommended for the majority of patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 35 percent and symptoms of heart failure. Some patients may be eligible for cardiac resynchronization therapy (see Chapter 7).

Stage D. Patients are severely ill and require special medical and/or surgical intervention. Intravenous diuretics and vasodilators may be appropriate for hospitalized patients. Some patients may be considered for a heart transplant, ventricular assist device (VAD), and/or investigational surgery or drugs. End-stage patients who are not eligible for any of these extraordinary procedures may be referred for hospice care.

Anemia and Heart Failure

Anemia is a common problem in heart failure, with approximately one-third of all heart failure patients suffering from the condition. Heart failure patients with anemia also suffer more symptoms and have increased rates of both hospitalization and death. Anemia in heart failure can be due to a number of different factors including iron deficiency or the inability of their kidneys to produce enough of the hormone erythropoietin, which plays a key role in the production of red blood cells. Additionally, the chronic inflammation seen in heart failure can make the bone marrow more resistant to the effects of erythropoietin. Some medications used in heart failure treatment, including some ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers, also can cause anemia.

As heart failure progresses, anemia becomes more common, affecting up to 70 percent of patients in New York Heart Association class IV. Anemia, which is associated with poor survival, can be caused or aggravated by sodium and water retention, kidney disease, and other processes associated with heart failure. There are seven types of anemia, but iron-deficiency anemia is the most common type. It is due to blood loss but may occasionally be caused by poor absorption of iron, according to the American Society of Hematology.

While treatment with erythropoietic agents (drugs that boost the production of red blood cells) may help anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease or chemotherapy-induced anemia, a large trial studying the effect of the erythropoietic agent, darbepoeitin alfa, in heart failure patients with anemia found an increased risk of blood clots and ischemic stroke with the drugs. In people who are iron-deficient, oral or intravenous iron supplementation can boost hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein found in red blood cells. Iron-replacement therapy has been shown to improve exercise tolerance, NYHA class, and quality of life.

Early Warning Devices

Because it is often difficult to balance medications to eliminate the maximum amount of sodium and water without upsetting the body’s chemistry, doctors are optimistic about the value of early warning devices. These implantable devices are designed to sense changes in intracardiac pressures that signal the beginnings of excess fluid buildup in the heart and lungs.

The CardioMEMS device has proven to be particularly successful in guiding medication management. The device enables a physician to adjust medications to prevent pulmonary edema and its consequences, ultimately making patients feel better and reducing crises that require hospitalization.

In a study of Medicare patients, the device reduced hospitalizations by 45 percent in the six months after the device was implanted, saving $13,000 per patient per year. A landmark trial called the CHAMPION trial, found that use of the CardioMEMS device significantly reduced both hospitalization and mortality rates in patients with systolic heart failure. The FDA approved the device for patients with NYHA class III heart failure who have been hospitalized for heart failure within the past year.

What’s Next?

Chapter 7 describes medical interventions needed to treat advanced cases of heart failure.

The post 6. Treatment: Taking the Right Medications appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 6. Treatment: Taking the Right Medications »