2. Cholesterol and Your Heart

To understand how cholesterol affects your cardiovascular health, it helps to understand the workings of your heart and vascular system.

The Heart

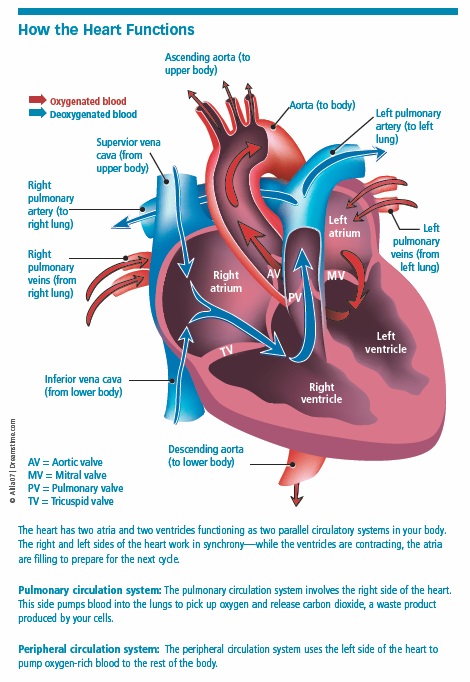

Think of your heart as a pump, about the size of a fist. It consists of two upper chambers (the left and right atria) and two lower chambers (the left and right ventricles) that work in synchrony.

Overall, the average heart contracts and relaxes—what we know as a heartbeat—about 100,000 times a day. In the process, it pumps approximately 2,000 gallons of blood daily.

On the right side: The right atrium receives oxygen-depleted blood from the inferior and superior vena cavae (the two largest veins in the body). The atrium contracts and pushes the blood through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. Once full, the right ventricle pumps blood through the pulmonary artery to the lungs, where the blood is re-oxygenated.

On the left side: The oxygenated blood returns via the pulmonary veins to the left atrium. From there, the atrium contracts and pushes blood through the mitral valve into the left ventricle. Now filled with oxygenated blood, the left ventricle pumps it out through the aorta and to the network of arteries, capillaries, and veins that channel blood throughout your body.

Your Vast Vasculature

It’s estimated that the human vascular system contains about 60,000 miles of blood vessels—enough to circle the Earth twice—that begin and end at the heart.

Arteries are elastic blood vessels that transport oxygenated blood away from the heart. The largest artery, the aorta, branches off into smaller arteries, which in turn divide into even smaller arteries, eventually leading to tiny blood vessels known as arterioles. The arterioles help manage the flow of blood into the microscopic capillaries found in your body’s tissues.

Some of the most important arteries in your body—the coronary arteries—do not carry blood away from the heart, but rather branch off from the aorta, traverse the outer surface of the heart (epicardium), and supply blood to the heart muscle, or myocardium. The left main coronary artery divides into the circumflex artery, which transports blood to the outer side and back of the left side of the heart, and the left anterior descending artery, which provides blood to the front of the heart’s left side.

The right coronary artery supplies blood to the right atrium and ventricle and, along with the circumflex artery, transports blood to the underside of the heart.

All of these larger coronary arteries further subdivide into smaller branches that deliver blood throughout the heart muscle. All arteries contain a wall of connective tissue and several layers of smooth muscle cells.

- The outermost layer (tunica externa) attaches the blood vessel to surrounding tissue.

- The middle layer, or tunica media, consists mainly of smooth muscle and is responsible for changing the diameter of the artery to help regulate blood pressure.

- The tunica intima, the innermost layer of the artery, includes the epithelium, a thin layer of tissue that helps regulate the transport of materials into and out of the bloodstream.

Capillaries, the tiniest and most abundant blood vessels in the body, form a bridge between the arteries and veins. They serve primarily as conduits allowing for the exchange of oxygen from blood in the arteries to tissue cells, and also the removal of carbon dioxide from the tissue cells into the veins for transport to the lungs and eventual removal from the body.

Veins, the other larger blood vessels in the body, transport blood from the bodily tissues back to the heart and then to the lungs to be re-oxygenated. The walls of the veins contain the same three layers as the arteries, but they’re thinner, partly because blood pressure in the veins is lower than it is in the arteries. However, the veins hold much more blood than the arteries—about 60 to 70 percent of your body’s total blood volume.

Cholesterol and Plaque in Your Arteries

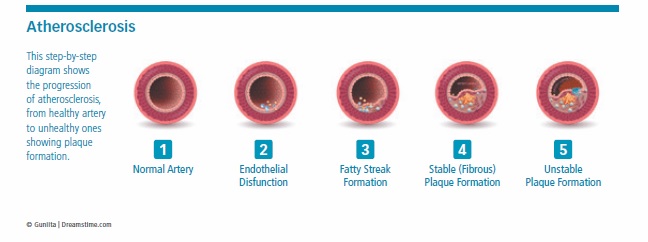

The accumulation of cholesterol-laden plaque in your arteries is a gradual, insidious process known as atherosclerosis, or “hardening” of the arteries. It usually begins in childhood or early adolescence with the formation of fatty, cholesterol streaks in the artery walls. Over the years, the disease progresses—rapidly for some people in their 20s; for others, not until their 50s or 60s.

Eventually, the normally smooth epithelium lining the inside of the arteries can become damaged as a result of high cholesterol and triglycerides, high blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, and other factors.

Endothelial damage opens the door for cholesterol, fats, calcium, and other materials to enter the artery wall, or tunica intima. This toxic blend triggers an inflammatory response by your immune system, which sends white blood cells (macrophages) to remove the cholesterol. The macrophages engulf and digest the cholesterol, and normally they would transfer it to HDL to be carried away and excreted. Instead, they take in so much LDL that they develop a foamy appearance, earning them the name foam cells.

As the cells accumulate, muscle cells from the tunica media move into the tunica intima and, along with cells known as fibroblasts, form a fibrous cap over the lesion. An atherosclerotic plaque, or atheroma, is born.

Over time, the plaques can become calcified. The buildup of plaques can greatly thicken the endothelium and narrow the artery, resulting in diminished blood flow.

When Plaques Rupture

If you’ve been given a diagnosis of coronary heart disease, your doctor might tell you that one or more of your coronary arteries is 70 to 80 percent blocked. You would think that such a large blockage would be much riskier than, say, a 40 percent blockage, but that’s not necessarily the case.

In fact, most heart attacks don’t result from an over-accumulation of plaque that completely blocks an artery, and many heart attacks occur in arteries that are less than 50 percent blocked. Oftentimes, the most dangerous plaques reside almost completely within the artery wall and do not significantly obstruct the blood vessel.

Rather, the real harm occurs when an atherosclerotic plaque ruptures. In response, platelets rush to the site and form clots to repair the damage. These clots can grow large enough to completely block a coronary artery and cause a heart attack.

If a clot obstructs an artery supplying the brain, an ischemic stroke occurs. Clots that block blood flow to the arms and legs cause peripheral artery disease (PAD) and, in severe cases, critical limb ischemia, which may lead to gangrene and amputation.

An Inflammatory Response

More and more, scientists have learned that cardiovascular disease is not just a “plumbing problem,” but rather a complex interplay of cholesterol, fats, and your body’s inflammatory immune response.

The immune system’s job is to neutralize threats that get past your outer defenses. It responds to infection and injury with inflammation that destroys the virus or other harmful intruders, but in the process it causes some collateral damage to healthy tissues, as well.

Experts now realize that your immune system perceives fatty, cholesterol-laden plaques lining your artery walls as abnormal, like a foreign invader, and sends white blood cells to shield them from your bloodstream.

However, this inflammatory response can destabilize the plaques and make them vulnerable to erosions and rupture, spilling their contents out into the bloodstream and exposing parts of the vessel wall not normally in contact with blood. This process then triggers platelet activation and formation of blood clots that may cause heart attacks or ischemic strokes.

Most arterial plaques do not rupture—by some estimates, only about two out of every 100 of them do—but determining which plaques are more susceptible to rupture, especially those hidden in the artery walls, has been difficult.

Researchers continue to develop new imaging and blood tests to better assess how much plaque lies within the artery wall and how vulnerable it is to rupture.

The Harms of Hyperlipidemia

High cholesterol can have wide-ranging effects—both direct and indirect—on your heart and several other organs served by your vascular system. As cholesterol builds in the arteries of your heart, brain, and throughout your body, it usually does so silently. In some cases, the first signs of atherosclerosis may be a cardiovascular event, such as a heart attack or stroke.

The Heart

Acute Coronary Syndrome

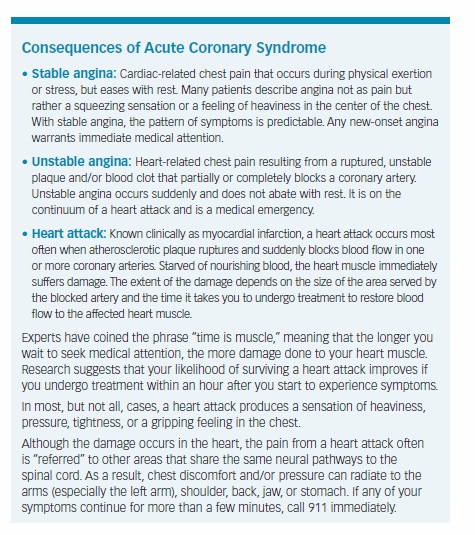

Cholesterol-rich plaques obstruct the coronary arteries, which provide the heart muscle with blood. Experts use the term acute coronary syndrome to describe situations in which atherosclerotic plaque accumulation or ruptures cause the narrowing or blocking of one or more coronary arteries, leading to inadequate blood flow to the heart muscle. These situations include stable angina, unstable angina, and heart attack (see sidebar on page 13).

Heart Failure

Atherosclerosis can contribute to heart failure (an inability of a weakened heart to pump blood adequately) in several ways. Coronary arteries narrowed by atherosclerotic plaque can reduce blood flow to the heart muscle, weakening it. The same occurs when a section of heart muscle is damaged during a heart attack.

Also, as arteries outside the heart become narrowed and hardened due to atherosclerosis, your heart has to work harder to pump blood out to your body. In response, your heart thickens and enlarges to meet the increased demands. Unfortunately, your heart can’t keep up this pace. Over time, the ventricles may stiffen, and the heart muscle may weaken.

Systolic heart failure occurs when the left ventricle does not contract forcefully enough to pump sufficient blood to the body. In diastolic heart failure, the heart contracts normally, but the ventricles do not relax enough to allow adequate blood to enter the heart during normal filling.

In some, but not all, cases, blood inadequately pumped from the ventricles can back up, or congest, in the lungs, abdomen, and lower extremities—the term “congestive heart failure” is derived from this complication. Heart failure patients may experience fatigue and breathing problems, weight gain, swelling in the lower extremities and abdomen due to fluid buildup, and increased/irregular heart rate.

Atrial Fibrillation (Afib)

Coronary artery disease and heart attack are risk factors for Afib, in which irregular electrical impulses cause the heart’s two upper chambers, the atria, to beat rapidly and erratically instead of contract and relax in a normal synchronized fashion. As a result, blood isn’t fully pumped out of the heart, but instead pools in the atria, where it can clot. These clots may break free from the atria, travel to the brain, and cause strokes. In fact, Afib is a leading stroke risk factor.

Afib affects anywhere from 2.7 million to 6.1 million people in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the risk increases with age. Some people experience paroxysmal Afib, episodes lasting for seconds to hours before subsiding, while others have persistent Afib that occurs continuously.

The Brain

Carotid Artery Disease

Cholesterol-laden plaque can accumulate in the carotid arteries, the two large arteries on either side of your neck that supply oxygen-rich blood to the brain. Carotid artery disease is a leading risk factor for stroke

Stroke

The cerebral arteries of the brain are among the many blood vessels damaged by atherosclerosis, so unhealthy cholesterol levels are a risk factor for stroke. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, stroke is the fifth-leading cause of death in the United States, and it’s also one of the leading causes of long-term disability.

Most strokes are ischemic strokes, or infarcts, which occur when a blood clot forms and blocks blood flow in the brain. Ischemic strokes also can originate in the carotid arteries. (A smaller percentage of strokes are hemorrhagic strokes, caused by ruptured blood vessels inside or on the surface of the brain.)

Having hyperlipidemia also may increase your risk of a transient ischemic attack (TIA), or “mini-stroke,” caused by brief, temporary blockages of blood vessels in or leading to the brain. TIAs commonly precede ischemic strokes, and evidence suggests that people who experience a TIA also are at greater risk of a subsequent acute coronary syndrome, which encompasses heart attack and angina (chest pain resulting from obstruction of blood flow to the heart muscle).

When a stroke occurs, the brain tissue served by the affected artery is deprived of nourishing blood and begins to die, much like the heart muscle supplied by a blocked coronary artery begins to die during a heart attack. Strokes can produce sudden numbness or weakness in the face, arm or leg, particularly on one side of the body, as well as difficulty communicating or understanding speech, vision problems in one or both eyes, confusion, dizziness, trouble walking, loss of coordination, and sudden, severe headache. (TIAs produce these same symptoms, but they last only briefly.)

Vascular Dementia

The human brain, on average, weighs about 3 pounds, accounting for only 2 percent of your entire body weight. Yet, your brain is one of the largest consumers of oxygen and blood in your body—about 20 percent of the blood pumped with each heartbeat goes to nourish brain cells—and it houses one of the most extensive networks of blood vessels.

So, it’s easy to see why anything that adversely affects the health of your heart and blood vessels can have a downstream effect on your brain function. Hyperlipidemia and other cardiovascular risk factors not only contribute to atherosclerosis and raise your risk of heart attack and stroke, but they also appear to increase your odds of cognitive disorders.

One of these disorders is vascular dementia, or vascular cognitive impairment, which occurs when damage to the cerebral blood vessels causes disruptions in the connections between areas of the brain or makes them less efficient. Cognitive problems from vascular dementia may occur rapidly after a stroke that affects one of the major brain blood vessels, or they may develop gradually due to cumulative damage from one or more minor strokes in the smaller cerebral vessels.

Vascular dementia is especially characterized by reductions in mental processing, slowed thinking, and problems with complex thought processes, such as planning, organizing, multitasking, and decision making. It can affect memory, and it also can occur simultaneously with Alzheimer’s disease. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, vascular dementia accounts for 10 percent of dementia cases, making it the second-most common type of dementia, behind Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s Disease

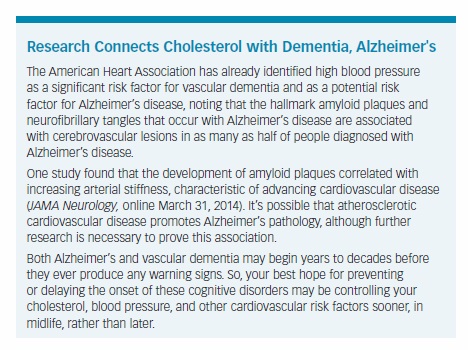

It’s easy to understand how hyperlipidemia is linked with vascular dementia, but some evidence suggests that it also may be connected with Alzheimer’s disease.

For example, a 2014 study found that high levels of HDL and low levels of LDL cholesterol were associated with lower levels of toxic amyloid plaque in the brain (a signature characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease), in a way analogous to the role these lipids play in cardiovascular disease.

The study included 74 men and women (average age 78)—including three people with mild dementia, 38 with mild cognitive impairment, and 33 who were cognitively normal—who underwent imaging scans of their brains to measure levels of amyloid plaques. The researchers found that the participants with higher fasting LDL levels and lower HDL levels had greater amyloid deposition in their brains (JAMA Neurology, February 2014).

Conversely, “Our study shows that both higher levels of HDL and lower levels of LDL cholesterol in the bloodstream are associated with lower levels of amyloid plaque deposits in the brain,” Bruce Reed, PhD, lead study author and associate director of the University of California-Davis Alzheimer’s Disease Center, said in a statement. “Unhealthy patterns of cholesterol could be directly causing the higher levels of amyloid known to contribute to Alzheimer’s, in the same way that such patterns promote heart disease.

“[The study] also suggests a method of lowering amyloid levels in people who are middle aged, when such build-up is just starting,” Dr. Reed continued. “If modifying cholesterol levels in the brain early in life turns out to reduce amyloid deposits late in life, we could potentially make a significant difference in reducing the prevalence of Alzheimer’s, a goal of an enormous amount of research and drug development effort.”

The Eyes

Retinal Vein Occlusion

High cholesterol, diabetes, and other cardiovascular risk factors contribute to this blockage of small veins that transport blood away from the retina. The blockage often occurs where arteries in the retina affected by atherosclerosis press on a retinal vein.

The blockage can lead to bleeding and fluid leakage from the blocked blood vessels. Symptoms include blurry vision or vision loss in all or part of one eye, occurring suddenly or worsening over the course of several hours or days.

The Limbs: Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD)

PAD occurs when fatty plaques accumulate in the peripheral arteries and limit blood circulation to the legs, feet, arms, and other locations away from the heart. The lack of blood flow jeopardizes the health of your legs and feet, resulting in foot amputation in less than 5 percent of PAD cases.

However, the biggest health threat to PAD patients is heart attack and stroke. PAD shares risk factors with heart attack and stroke: hyperlipidemia, obesity, high blood pressure, and, especially, smoking and diabetes. Some 80 percent of people with PAD also have blockages in their coronary arteries.

The American Heart Association estimates that people with PAD face a four to five times greater risk of heart attack and stroke compared to those without the disease.

The classic symptom of PAD is intermittent claudication, pain in the calves, thighs, or buttocks brought on by walking that typically eases with rest. However, research suggests that this symptom occurs in only about 11 percent of PAD patients. PAD also may cause coldness or loss of hair in the lower leg or foot, changes in the color or texture of the skin on your legs and feet, changes in toenail growth and texture, and, in some men, erectile dysfunction.

Sexual Function

Erectile Dysfunction (ED)

ED may develop when the arteries supplying blood to the penis become damaged or blocked due to atherosclerosis, caused by high cholesterol, hypertension, and other risk factors.

Conversely, many experts now consider ED as a harbinger of coronary heart disease, and that ED may precede heart disease by up to four years, as the smaller arteries of the penis are affected before the larger coronary arteries.

In a meta-analysis of 11 clinical trials, researchers found that men with erectile dysfunction who took cholesterol-lowering statin medications experienced improvements in their erectile function (Journal of Sexual Medicine, July 2014).

“The increase in erectile function scores with statins was approximately one-third to one-half of what has been reported with drugs like Viagra, Cialis, or Levitra,” the study’s lead investigator, John B. Kostis, MD, director of the Cardiovascular Institute at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, said in a statement. “It was larger than the reported effect of lifestyle modification. For men with erectile dysfunction who need statins to control cholesterol, this may be an extra benefit.”

If you have ED, talk to your doctor about undergoing a cardiovascular risk assessment, which includes measurements of your cholesterol, blood pressure, and other risk factors.

Female Sexual Dysfunction

Just as hyperlipidemia, via atherosclerosis, can restrict blood flow to the penis and contribute to erectile dysfunction, it also may contribute to female sexual dysfunction, some evidence suggests. The arterial damage caused by atherosclerosis may affect the vessels supplying blood to the vagina and may potentially cause problems such as vaginal dryness or decreased sex drive or arousal.

In one study, Italian researchers measured LDL, HDL, and triglyceride levels in 466 women, ages 42 to 58, and surveyed them about their sexual function. Compared to their counterparts with normal cholesterol levels, women with hyperlipidemia were more likely to experience problems with sexual arousal, orgasm, satisfaction and pain, and reported greater levels of distress regarding their sex lives (Journal of Sexual Medicine, January 2013).

The post 2. Cholesterol and Your Heart appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 2. Cholesterol and Your Heart »

Powered by WPeMatico