6. Medication for Arthritis

illions of Americans suffer on a daily basis from the pain, reduced mobility, and loss of function caused by arthritis. The condition can significantly affect work, leisure, and home life. Chronic pain, a common feature in arthritis, can rob the sufferer of his or her joy and zest for life. A crucial weapon in the fight against arthritis is medication, which relieves pain and in some cases may slow the progression of the disease. The ultimate aim is to improve quality of life and optimize function.

Arthritis Pain Management

Pain is the most common symptom in arthritis and can be distressing and disruptive. It can be sudden and short-lived (acute) or drag on for months or years (chronic). Discomfort ranges from an annoying ache to excruciating pain that causes the individual to grind to a halt, unable to function. Acute pain usually occurs due to injury or inflammation of tissue and settles once the underlying condition resolves. Chronic pain, however, is a complex and mysterious condition.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution for pain; trial and error may be required to find a strategy that works for the individual. Understanding the science behind pain can help sufferers come to terms with and better manage their condition.

The Pathology of Pain

Acute Pain

Pain is an alarm signal that something is harming your body and that you need to take action. The source may be a pin sticking in your finger or inflammation in your joint.

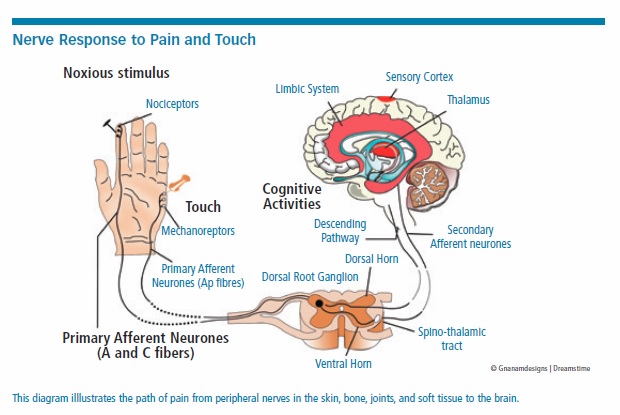

The pain pathway begins in the peripheral nerves of the skin, bone, soft tissue, or joints. Nervous signals travel to the spinal cord, then up into the brain, where pain is processed and a response is initiated. The process involves electrical and neurochemical signals. In the spinal cord, the dorsal horn area acts as a gatekeeper

for the pain, sometimes blocking minor pain, but allowing more significant signals to pass.

Joint pain arises from tissue in and adjacent to the joint, including the joint capsule, bone, ligaments, synovial membrane, muscle, and skin, but not cartilage, which has no nerve endings. Clinicians aim to determine the origin of the pain to guide diagnosis and treatment.

Joint pain may be caused by inflammatory disease, crystal deposition, infection, trauma, or a structural abnormality.

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is defined as pain lasting more than three months. In arthritis, much of this pain comes from the ongoing disease process.

Many forms of arthritis are progressive, with joint damage increasing over time. Tissue hyperplasia (overgrowth), bone erosion, soft tissue inflammation, nerve impingement, bony spurs catching on soft tissue, and loose bodies within the joint are just some of the physical causes of ongoing pain. Even when there is a physical cause for pain, people experience it very differently. Perception is everything.

An article in the British Journal of Pain outlined the factors influencing experience of pain perception:

- Cause of pain. The site, tissue involved, and disease process play a role in pain.

- Mental health. Anxiety, depression, tendency towards negative thinking, history of trauma, and abuse all come into play.

- Other conditions. Such chronic illness as heart and respiratory disease influence pain.

- Smoking. Research suggests that smokers report greater pain intensity than non-smokers.

- Alcohol. A few glasses of alcohol may cause temporary pain reduction, but it is not recommended as a treatment for pain due to the risk of inebriation, alcoholism, and other negative health effects. During alcohol withdrawal, pain sensitivity is increased.

- Weight. Being overweight not only puts greater pressure on stressed joints but may also increase pain sensitivity.

- Physical activity. In some conditions, such as ankylosing spondylosis, exercise relieves pain. With other arthritic conditions, the link is less clear.

- Sleep problems. Herein lies a vicious cycle. Pain disrupts sleep, and lack of sleep increases pain perception.

- Nutrition and pain. There is some evidence that a healthy diet and omega-3 fish oils reduce inflammation, and thus pain, in inflammatory arthritis.

- Employment. Some occupations increase the risk of arthritis and exacerbate pain.

- Sunshine and vitamin D. There is a possible relationship between low vitamin D and increased pain sensitivity.

- Old age. Older people suffer from more chronic pain than younger people. However, it is hard to tease out whether increasing age causes changes in pain perception, or whether there is just more disease causing pain.

- Gender. There is a higher prevalence of chronic pain in women, who have lower pain thresholds and tolerance and are more likely to seek medical advice for pain.

- Ethnicity and culture. Some ethnic and demographic groups have a higher pain sensitivity.

- Genes. Chronic pain conditions run in families, and hundreds of genes have been identified that may impact pain sensitivity and tolerance.

Neuropathic Pain

On top of the physical pain of chronic arthritis, neuropathic pain may also develop. Nervous pathways become rewired and oversensitive, producing pain signals with little or no cause. This pain is often described as “tingling,” “stabbing,” “burning,” “pins and needles,” or “numbness.”

Diagnosing Arthritis

If you have mild joint pain of recent onset, you may be able to self-medicate with over-the-counter analgesics such as acetaminophen or NSAIDS (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) such as ibuprofen.

If, however, pain is severe or lasts more than a few days, it is important to see your doctor for diagnosis. In Chapter 2, we explored the diagnostic evaluation of joint pain in detail. Once the cause has been ascertained, a treatment plan can be devised.

First-Line Drug Treatment

No matter the cause of the arthritis, first-line treatment usually involves pain relievers called analgesics. Don’t be lulled into thinking over-the-counter analgesics are completely safe; all drugs have side effects and interactions, so check instructions carefully. For information on medications, side effects, and interactions, visit www.medlineplus.gov/druginfo.

First-line drugs can be given orally, topically (on skin), or via local injection or infusion.

Oral Analgesics

- Acetaminophen

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Corticosteroids

- Opioids.

Topical Analgesics

- Counterirritants

- Capsaicin creams

- NSAIDs

- Local anesthetic

- Opioids.

Local Injection (Joint Space, Muscle, Tendon, Bursae)

- Corticosteroids.

Infusion (Into Blood Stream)

- Corticosteroids

- Opioids: Rarely for acute, severe pain.

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen is an analgesic (relieves pain) and an antipyretic (reduces fever) drug, but it is not anti-inflammatory. It works by blocking pain signals in the brain. It can be useful as a stand-alone in mild joint pain for those who can’t take NSAIDs or as an addition to NSAIDs and other treatments.

Potential Side Effects

Acetaminophen, at the recommended dose, is relatively safe for long-term use, except in those with liver disease. Overdose is dangerous and can cause irreversible liver damage.

Accidental overdose may occur when people are taking acetaminophen with cold and flu remedies, so read the labels carefully and discuss with your pharmacist if you are not sure.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs reduce inflammation, pain, and fever. Low doses are available over the counter, but stronger formulations require a prescription. Low doses may be enough for mild disease but might not cut it in advanced disease or acute flare-ups. NSAIDs should be taken at the lowest effective dose, and for the briefest duration possible, to achieve symptom relief and keep side effects to a minimum. In rheumatoid arthritis, NSAIDs may be used to tide over a patient while he or she is waiting for disease-modifying drugs to take effect.

NSAIDs interact with many other drugs (especially anti-clotting drugs like warfarin), so always check with your pharmacist or doctor to see if they’re safe to take. People with asthma and women who are pregnant or breastfeeding need to check with their doctor before taking NSAIDs.

Potential Side Effects

NSAIDs are relatively safe—if used in the recommended doses and for short periods. Common side effects include:

- Inflammation of the stomach lining leading to indigestion or mild discomfort, and in severe cases stomach ulcers and bleeding. This is more common in smokers, in cases of prolonged use, and in those with pre-existing stomach problems, who are over 60 and who take oral steroids.

- Headaches, drowsiness, and dizziness.

- Raised blood pressure and small increased risk of heart attack and stroke, with prolonged useage (not with aspirin).

- Kidney damage, especially in cases of prolonged use and overdose.

These side effects are dose-related, and are less common with topical formulations.

Reducing the Risks of NSAIDs

In order to reduce gastric side effects, there are several strategies that may help: Take coated pills, always take with food, keep dosage low, and never mix NSAIDs. If you’re suffering with gastric symptoms, you may want to try an antacid such as proton-pump inhibitors (e.g. omeprazole) or histamine (H2) blockers (e.g. ranitidine or cimetidine). If symptoms persist, your doctor may prescribe misoprostol (Cytotec), which inhibits the secretion of gastric acid and strengthens the stomach lining. Be aware that the more different medications you take, the greater the risk of problematic interactions.

COX-2 Inhibitors

COX-2 inhibitors such as celecoxib (Celebrex) are a new group of NSAIDs that cause less gastric irritation while providing similar pain relief and anti-inflammatory relief as traditional NSAIDs. There are, however, safety concerns with these drugs over increased cardiovascular risk in those with pre-existing heart disease.

Corticosteroids/Steroids

Corticosteroids are powerful anti-inflammatory drugs that are commonly used in arthritis care to provide pain relief and slow inflammation.

Use in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other autoimmune arthritis. Cortisone, the first corticosteroid, revolutionized RA care after its introduction in 1949. Corticosteroids remain useful in the battle against inflammatory arthritis and are often used during flare-ups and in combination with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), particularly to bridge the gap while DMARDs take effect. (We discuss DMARDs later in this section.) They can be given as a pill or injection and are fast-acting.

Use in osteoarthritis (OA). Corticosteroid injection into the joint space may be useful in OA to provide short-term relief. Epidural injections of corticosteroids and lidocaine can be used when pain from spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal) is severe. Injections should be limited to no more than three per year and 10 total, for each joint, to reduce the serious risk of fracture.

Potential Side Effects

Corticosteroids come with significant potential side effects, which are generally dose-related. The most common are:

- Bone loss and increased fracture risk

- Raised blood sugar and risk of diabetes

- Weight gain

- Immunosuppression and increased risk of infection

- Cataracts and glaucoma

- Hypertension

- Stomach ulcers

- Easy bruising

- Fatigue, mood changes, and weakness, especially on withdrawal.

The search is under way for corticosteroid formulations with fewer side effects.

Opioids

Sometimes the pain of arthritis is so severe that other first-line drugs are inadequate. Opioid drugs or narcotic analgesics are powerful analgesics that can cut through severe pain, but carry significant risks.

Potential Side Effects

Side effects are common with opioids and include:

- Nervous system depression can include drowsiness, sedation, confusion, impaired judgement, falls, accidents, and even death. This can be exacerbated if combined with alcohol or taken in excess, and is more problematic in the elderly.

- Respiratory depression, including shortness of breath and shallow breathing, may lead to low oxygen levels in blood (hypoxia).

- Atrial fibrillation and stroke.

- Pruritis (itching).

- Constipation, nausea, or vomiting.

- Withdrawal symptoms may be severe and can include anxiety, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

Overdose may occur when taken in excess, with symptoms including decreased level of consciousness, pupil constriction, and respiratory depression, which may lead to seizures, muscle spasms, and death.

Opioid misuse and addiction are serious problems, often beginning with innocuous use in pain management. Tolerance increases over time and patients may find themselves taking higher and higher doses to achieve pain relief. As dosage increases, so do side effects. Regular use can lead to dependence, and unpleasant withdrawal symptoms make it difficult to stop opioid use. There is also a significant risk of misuse by family members, especially teens, if opioid medications are not stored carefully.

Topical Analgesics

Topical analgesic pain relievers are applied to the skin close to the source of pain and may provide much-needed temporary relief. Some are available over the counter without prescription. Avoid contact with eyes, nose and mouth.

Counterirritants

These create a temporary hot or cold sensation on the skin, interrupting the perception of pain. Active ingredients include menthol, eucalyptus, camphor, and wintergreen (methyl salicylate). Most have a strong odor and may cause slight skin irritation.

Capsaicin Creams

Capsaicin is the active ingredient found in hot peppers. When formulated into topical creams, it can provide localized pain relief by interfering with pain signals.

Topical NSAIDs

NSAID gels and patches allow local delivery of NSAID drugs while limiting systemic side effects. They’re particularly useful when pain originates in superficial soft tissue such as tendons and bursae. Examples: iclofenac sodium (Voltaren Gel) and the diclofenac patch (Flector Patch). Side effects are dose-related (see “Potential Side Effects” in NSAIDs section above). Some of the drug will enter the bloodstream, so it’s important to use sparingly and be wary of interaction with oral medications.

Lidocaine Patch (Lidoderm)

Lidocaine is a local anesthetic that can be used in a patch form to relieve pain in the back and larger joints. The patch measures 5 by 6 inches and can be used for 12 hours per day.

Fentanyl Patch (Duragesic)

Fentanyl is a powerful opioid analgesic that has been formulated into a transdermal patch for use in severe chronic pain. The patches are slow-release and can be used every three days. Potential side effects are those of opioids in general (see above), so they should be used with care.

Medication for OA

OA was long believed to be a disease of wear and tear, but mounting evidence points to an underlying inflammatory cause. Traditionally, it has been treated with first-line medications (described above) and/or surgical interventions, physical therapy, and complementary treatments. Eventually, OA may be treated more often with drugs originally designed for RA, but this is currently at the research phase.

Hyaluronic Acid Injections/ Viscosupplements

Arthritic joints may benefit from injection with hyaluronic acid (a thick, sticky liquid) to compensate for lack of synovial fluid and improve lubrication of the joint. Licensed for OA of the hip, viscosupplements are also used by some clinicians in the hip and ankle. They are most effective in moderate disease and may give relief for up to six months.

Side effects are uncommon and include mild inflammation at the site of the injection.

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP)

Platelets are blood cells that cause clotting. They contain growth factors that can enhance healing in damaged tissue.

In the PRP procedure, blood is drawn from the patient and processed to separate platelets, which are then concentrated, mixed with blood plasma, and then injected into the site of the damage.

Originally used to treat tendon injuries, PRP is increasingly being used in OA. A 2017 study in the International Journal of Surgery concluded that “PRP injection appears to be effective in early symptomatic OA knees…. Three injections per month yielded significantly better results in short-term follow-up.”

Prolotherapy Injections

Over time in the OA process, tendons and ligaments become loose, leading to pain. Prolotherapy is a procedure that aims to tighten this tissue. A series of dextrose injections are given into the ligament or tendon, causing inflammation, scarring, and ultimately new tissue growth and improved vascularization (blood supply).

Stem Cell Therapy

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), a promising new treatment for OA, are still at the research stage. MSCs are derived from bone marrow or adipose tissue (fat) and then grown in the lab. These cells are then delivered by implantation into bones or injection into the joint, helping repair of the damaged tissue.

Managing RA with DMARDs

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, or DMARDs, interfere with the immune reaction, slowing progress of disease and potentially reducing or preventing joint destruction. Because they alter the immune system, there are significant potential side effects requiring expert monitoring.

DMARDs fall into three groups: Traditional non-biologics, newer biologics, and synthetic kinase inhibitors.

Non-Biologic DMARDs

Drugs include:

- Methotrexate (Folex, Rheumatrex, Otrexup, Trexall)

- Leflunomide (Arava)

- Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil)—originally a malaria treatment

- Sulfasalazine (Azulfidine).

This group of drugs can be highly effective, if prudently prescribed, and have an excellent side effect profile. They are now recommended as first-line treatment in RA, and should be considered as soon as diagnosis is confirmed, as they may halt disease progression and reduce the need for pain relief and other interventions.

It takes time for non-biologic DMARDs to reach a therapeutic level in the bloodstream, so it may be six weeks before any effect is seen and 12 weeks for the full benefits. Oral formulations are usually given first, and if they do not help, injections or combinations of DMARDs may be used. These drugs have a systemic effect (whole body) so not only do they help with joint disease, but they also reduce the risk of heart and other extra-articular disease.

Typically, non-biologic DMARDs are combined with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or corticosteroids, at least early in the treatment. They are not safe in pregnancy and may lower sperm production in men. Alcohol intake should be stopped or limited during therapy and for three months after cessation.

Potential Side Effects

Mild side effects of DMARDs include nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, drowsiness, swollen gums, dizziness, decreased appetite, and hair loss. Susceptibility to infection is increased.

More serious side effects should be reported to a doctor immediately and may include sore throat, fever, chills, severe headache, seizures, mouth sores, diarrhea, unusual tiredness, pale skin, dark or reduced volume of urine, persistent nausea or vomiting, severe pain, jaundice (yellowing of skin or eyes), unusual bruising or bleeding, black stools, enlarged lymph nodes, bone pain, shortness of breath, dry cough, and muscle weakness, especially if one-sided. These symptoms may herald serious life-threatening complications, so patients should err on the side of caution.

Second-Line Drugs

These drugs suppress the inflammatory process by interfering with immune system chemistry. They are the most powerful RA drugs but carry considerable side effect risks and a high price tag. They should be used only when first-line treatments have been exhausted. They include biological DMARDs and Janus Kinase Inhibitors.

Biologic DMARDS

According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), “Biological products are made from living organisms… (There are) many sources, including humans, animals, and microorganisms such as bacteria or yeast.” These are a newer class of drug, derived from bioengineering of genetic material to create active proteins, which alter biological processes within the body.

Biologic DMARDs are reserved for those with moderate-to-severe RA who have not responded to NSAIDs or non-biologic DMARDs. Their effect is targeted to modify the immune response by interfering with inflammatory chemicals (cytokines) such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-1, and interleukin-6. Each group of Biologic DMARDs targets a specific mechanism within the immune system.

Potential Side Effects of Biologic Dmards

Because these drugs target the immune system, they may cause side effects in several body systems. They weaken the immune system and so increase the risk of getting very ill from opportunistic infections, including tuberculosis (TB). There is an increased risk of certain cancers, such as skin cancer and lymphoma, but it is unclear whether this is due to the drugs or RA.

Symptoms that should be reported, if severe or persistent:

- Headache

- Runny nose

- Sore throat

- Flushing

- Nausea

- Dizziness

- Heartburn

- Pain in back, arm, or leg.

If you experience more serious side effects, call your doctor immediately:

- Hives, skin rash or itching

- Swelling of the eyes, face, lips, tongue, or throat

- Fever, chills, and other signs of significant infection

- Difficulty breathing or swallowing

- Arrhythmias (irregular heartbeat) or low blood pressure

- Shortness of breath or persistent dry cough

- Weight loss

- Night sweats

- Frequent urination, burning sensation, or urgency

- Cellulitis (inflamed, red, hot, swollen area on the skin).

Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor (Anti-TNF) Drugs

These biologic DMARDs work by blocking the action of the inflammatory cytokine, called tumor necrosis factor (TNF). During a flare-up, they are often given in combination with methotrexate if methotrexate alone does did not suffice.

Up to 70 percent of RA patients respond well to Anti-TNFs. They cannot be taken orally, so they’re given either subcutaneously (SC) or by intravenous infusion (IV). Subcutaneous options may be self-administered at home, after medical instruction, but IV options are given in a clinic.

Anti-TNF agents include:

- etanercept (Enbrel)—SC

- infliximab (Remicade)—SC

- adalimumab (Humira)—SC

- golimumab (Simponi)—SC or IV

- certolizumab (Cimzia)—IV.

Rarely, long-term MS-like (multiple sclerosis) neurological side effects can occur. Those with MS should not take Anti-TNFs, and those with heart failure should not take infliximab.

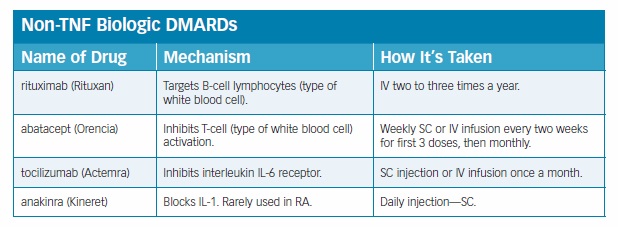

Biologic Dmards: Non-Tnf Agents

These are usually reserved for patients with moderate to severe RA who have not responded to Anti-TNFs. They are often used in combination with methotrexate.

Janus Kinase Inhibitors (JAK or Jakinibs)

These are synthetic drugs that interfere with the inflammatory mechanism within the cell. They are approved for patients with moderate-to-severe RA who have not responded to anti-TNFs.

The main drug is tofacitinib (Xeljanz) and the major benefit is that it can be taken in pill form daily. Potential side effects are similar to biologic DMARDs, with TB and shingles being notable risks.

Janus Kinase Inhibitors are the new kids on the block in RA treatment, and experts predict they will have an increasing role in treatment as more research emerges.

Biosimilars and Interchangeables

Biologic drugs are made using biotechnology, and are expensive to producert and expensive to buy. Pharmaceutical companies have developed techniques to make almost identical compounds, using chemical processes rather than biological ones.

The FDA describes biosimilars as drugs that “have been shown to have no clinically meaningful differences from the reference product” and interchangeables as drugs that are “expected to produce the same clinical result as the reference product.”

The first RA drug, infliximab-dyyb (Inflectra), a biosimilar version of infliximab, was approved by the FDA in 2016. Since then, etanercept-szzs (Erelzi), biosimilar to etanercept, and adalimumab-atto (Amjevita), biosimilar to adalimumab, have been approved. These drugs are new and have not been fully evaluated; some clinicians are concerned they will not be as effective.

Guarding Against Dmard Side Effects

The American College of Rheumatology recommends vaccination against pneumococcus, hepatitis, influenza, human papillomavirus (HPV), and herpes zoster (HZV) before starting DMARDs.

Finding the Right Drug Combination

The aim of treatment is to find a good balance between symptom relief, prevention of joint damage, and unwanted side effects. This can be tricky, involving months of trial and error for the individual and their doctor.

In most people, a combination of NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and DMARDs is used. Financial implications need to be considered, as biologics cost 10 to 20 times more than triple therapy involving non-biologics methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine.

New therapies are emerging frequently with the aim of improving outcomes, reducing side effects, and driving down costs.

Measuring Response

The aim of long-term rheumatoid arthritis treatment is to maintain “tight control of RA.” That means keeping severity of the disease low while keeping side effects manageable.

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommends the use of one of several instruments for measuring severity of disease: Examples include the Patient Activity Scale (PAS) and Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3).

Level of disease activity is categorized into four groups: remission, low, moderate, and high activity.

Ongoing treatment will be adjusted accordingly.

The ACR offers comprehensive research-based treatment guidelines for clinicians based on whether the disease is early stage or established disease, if the patient is DMARD naive (never been treated). Level of disease activity and response to treatment also are factors. Let’s just say it’s very complicated and that it’s best to leave these treatment decisions to the experts.

Tapering Therapy

As you have learned, DMARDs are expensive and come with many serious potential side effects. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommends that if RA is in remission, drugs can be tapered off, either by reducing the dose or using wider spacing of doses. They do not recommend completely stopping treatment, as research suggests this may trigger a flare-up in disease.

The post 6. Medication for Arthritis appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 6. Medication for Arthritis »

Powered by WPeMatico