3. Fundamental Nutrients

Fats, Carbohydrates, and Protein

You hear a lot about “nutrients,” by which people typically mean vitamins, minerals, or even less-well-known nutrients such as flavonoids. The fundamental nutrients, however, are the familiar fats, carbohydrates, and protein. These are so basic to the nutritional quality of the foods we eat that their relative proportions are actually used to calculate how many calories are in a food. Rather than measure calories by literally burning up a food, most food manufacturers simply do the math: Fats have nine calories per gram, while carbohydrates and protein contain four calories. (When fiber, a form of carbohydrate, passes through the body without being digested, its calories don’t “count.”)

Total Fat Doesn’t Count

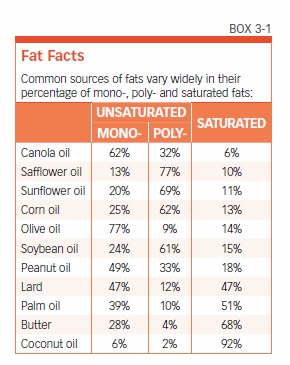

The message that not all fat is bad for you hasn’t gotten through to many people even today. All that worrying about the “Total Fat” line on the Nutrition Facts panel is a waste of time: Some types of fat—monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, like those found in liquid vegetable oils, nuts, and avocados—are actually good for your heart. That probably means they are also good for your brain. Fat is also an important component of cell membranes in the brain and of the myelin coating on neurons, which speeds up the transmission of information in the nervous system (see Box 3-1, “Fat Facts”).

The latest Dietary Guidelines for Americans reversed 35 years of nutrition policy by omitting any recommended limit on total fat intake. In 1980, the federal Dietary Guidelines first recommended limiting dietary fat to less than 30 percent of calories; in a 2,000-calorie daily diet, that advice translated to a maximum of 65 grams of fat per day. The 1980 recommendation was revised in the 2005 guidelines to a range of 20 percent to 35 percent of calories from total fat. The percentages used in the Nutrition Facts panel, however, continue to be based on the 1980 recommendation of 30 percent or 65 grams.

Fats, Mediterranean Style

It’s no coincidence that the Mediterranean-style diet, which seems to have cognitive benefits, is rich in healthy unsaturated fats. Scientists have found that increasing the intake of monounsaturated fats, as in olive oil, and of polyunsaturated fats, as in nuts, can help the brain perform its vital functions.

Participants in the PREDIMED-NAVARRA trial who followed a Mediterranean-style diet and also consumed at least four tablespoons of extra-virgin olive oil a day scored significantly better on two tests of mental abilities than a control group that was assigned to a low-fat diet. Those assigned to a Mediterranean plan supplemented with about a quarter-cup of walnuts, almonds, and hazelnuts daily also scored better than the control group. After more than six-and-a-half years of follow-up, fewer participants consuming either of the Mediterranean‑style diets were diagnosed with dementia than individuals in the control group.

The two Mediterranean groups actually consumed more total fat than the controls—but the fat was primarily heart-healthy monounsaturated (olive oil) or polyunsaturated (nuts). This finding further supports the apparent brain benefits of switching fats, rather than cutting down on fats of all types.

Go Unsaturated

In another study, scientists compared adherence to a Mediterranean-style eating pattern to white matter hyper-intensity volume (WMHV), a marker for small-blood-vessel damage in the brain. Participants completed food-frequency questionnaires to assess their diets and underwent MRI scans of their brains.

After adjustment for other risk factors, only one component of the Mediterranean diet was independently associated with WMHV: The ratio of monounsaturated fat to saturated fat. As the dietary share of monounsaturated fat rose versus saturated fat, WMHV declined. That suggests, researchers concluded, the overall dietary pattern rather than individual nutrients is responsible for healthier brains.

Butter and Other Saturated Fat: Still Don’ts

A few recent studies—and popular headlines—have cast doubt on the association between saturated fat and unhealthy cholesterol levels, some even proclaiming that “butter is back.” Tufts experts, however, say, “Not so fast.”

“We have strong data that substituting polyunsaturated fats for saturated fats decreases the risk of heart disease,” says Tufts cardiovascular nutrition expert Alice H. Lichtenstein. She adds, “We also have strong data that substituting carbohydrates, particularly refined carbohydrates, for saturated fats does not reduce risk.” When data from studies that examine the effects of substituting polyunsaturated fats are analyzed together with those substituting carbohydrates for saturated fats, she says, the results can cause confusion.

Saturated Fat and Your Brain

What about cognitive effects? A recent review of the science published in Neurobiology of Aging generally supported a link between saturated fat intake and risk of Alzheimer’s and dementia. Although some findings were mixed, saturated-fat intake was positively associated with Alzheimer’s risk in three of four cohort studies. The review also found a positive association between saturated-fat intake and risk of dementia (one of two studies reviewed), risk of cognitive decline (two of four studies), and risk of mild cognitive impairment (one of two).

Previously, findings from the Women’s Health Study showed that women who ate the most saturated fat had poorer scores on cognitive tests than those who consumed the least and were about 65 percent more likely to experience a decline in mental performance over time. The total amount of fat intake did not really matter, but the type of fat did.

Keys to Cholesterol

Along with trans fat, saturated fat is believed to contribute to unhealthy cholesterol in your bloodstream, called “serum” cholesterol. That cholesterol—a waxy, fat-like substance—is not the same as the dietary cholesterol listed on Nutrition Facts panels. The latest expert guidance largely dismisses concerns over intake of dietary cholesterol, such as that found in eggs and shellfish.

Your body needs a little serum cholesterol. But your body can make all the cholesterol it needs, primarily in the liver; any extra cholesterol can get deposited in artery walls.

Atherosclerosis Risks

This accumulated cholesterol eventually forms plaque, which narrows blood vessels and makes them less flexible—resulting in atherosclerosis, popularly known as “hardening of the arteries.” Since your brain uses such a high proportion of your body’s blood flow, anything that affects your circulation also impacts your brain (see Box 3-3, “Cholesterol Process”).

The Diabetes Heart Study-Mind found that such changes in the vascular system were related to cognition even before the changes became clinically apparent and treatable. Researchers measured the amount of calcified plaque in participants’ coronary arteries when the study began. Seven years later, a battery of cognitive tests measured subjects’ memory, processing speed, and executive function: Those with greater plaque at baseline scored lower on those mental tests.

Your Cholesterol Numbers

Just as oil and water don’t mix, fatty serum cholesterol and watery blood can’t directly combine. So, cholesterol in your blood rides along in packages called lipoproteins, which have cholesterol inside and protein on the outside. The two main types of these lipoproteins are what are actually measured when the lab tests your cholesterol. Here is what those numbers mean:

- Low-density lipoprotein, or LDL, is known as “bad” cholesterol because it carries cholesterol to your tissues. When too much LDL circulates in the blood, it can slowly build up in the walls of the arteries that supply blood to the heart and brain. According to the American Heart Association, an LDL cholesterol level of 130 to 159 mg/dL (milligrams per deciliter) is “borderline high,” 160 to 189 mg/dL is “high,” and 190 mg/dL and above is “very high.”

- High-density lipoprotein, or HDL, carries cholesterol from tissues to the liver, which removes it from the body; this earns it the nickname of “good” cholesterol. A level of at least 40 mg/dL for men and 50 mg/dL for women is associated with lower risk; the higher the HDL, the better.

- Triglycerides are another form of fat in your blood. Calories you consume that are not used immediately by the body’s tissues are converted to triglycerides and transported to fat cells to be stored. Hormones regulate the release of triglycerides from fat tissue to meet the body’s energy needs between meals. An excess of triglycerides in the blood, a condition called hypertriglyceridemia, is linked to the occurrence of coronary artery disease in some people. According to the American Heart Association, a triglyceride level of 150 to 199 mg/dL is “borderline high,” 200 to 499 mg/dL is “high,” and 500 mg/dL and above is “very high.”

Statins Plus Diet

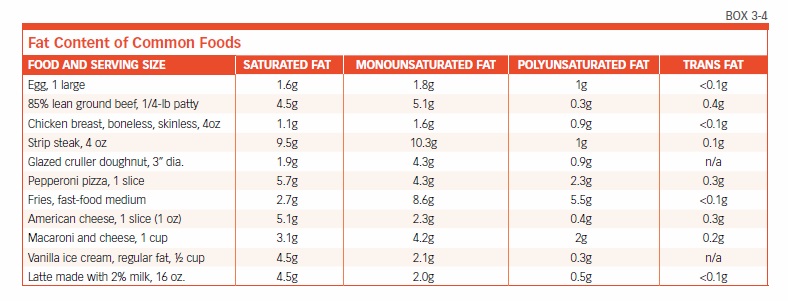

For most people, statin medications are powerfully effective for reducing cholesterol. levels But you can also improve unhealthy cholesterol levels by adjusting your diet. To reduce LDL cholesterol, the American Heart Association recommends limiting saturated-fat intake to five to six percent of your total calories (see Box 3-4 “Fat Content of Common Foods”). For most people, this means cutting saturated-fat intake roughly in half; the current average intake is 11 percent of calories. In a 2,000-calories daily diet, five to six percent of calories would equal 100 to 120 calories a day from saturated fat. That translates to roughly 11 to 13 grams of saturated fat per day, or a little less than the saturated fat in two tablespoons of butter or a five-ounce serving of rib-eye steak.

It’s key to replace those unhealthy fats with healthy ones—not, as in the fat-free fad of recent years, with refined carbohydrates. For best results, experts advise, substitute polyunsaturated fat for saturated fat. Next best is monounsaturated fat.

You also should avoid trans fats, found in partially hydrogenated oils used in some baked goods and packaged products. Both saturated fats and trans fats raise LDL; trans fats also lower healthy HDL.

HDL and Cognition

Scientists continue to investigate the role of that “good” cholesterol in your body. Some studies have failed to find benefits from boosting HDL cholesterol, suggesting that this number may actually be just a marker for an overall healthy lifestyle.

On the other hand, a study of 3,673 men and women suggests that higher HDL cholesterol might benefit the brain. Researchers measured cholesterol levels twice, at average ages 55 and 61, and short-term verbal memory was tested at each age. Initially, participants with low HDL (less than 40 mg/dL) scored lower on the memory test than those with high HDL (60 mg/dL or higher), but the difference wasn’t statistically significant. After five years, however, the difference increased to become significant. Moreover, individuals whose HDL levels declined during the five-year interval were more likely to also show a decline in memory performance than those whose HDL levels did not change.

The researchers speculated that HDL might protect cognitive function by reducing the risk for stroke and vascular disease, or HDL could moderate beta-amyloid, which is associated with plaques in the brain. Additionally, HDL may have anti-inflammatory or antioxidant effects, which could help to prevent the degeneration of the brain’s neurons.

You can maintain healthy HDL levels by not smoking, avoiding trans fats, and losing weight. Factors thought to boost HDL include exercise, moderate alcohol consumption, and intake of soluble dietary fiber, such as that found in oats, vegetables, fruits,

and legumes.

Inflammation and Chronic Disease

Inflammation is part of your body’s natural defense mechanism, but chronic inflammation in the blood vessels can allow LDL cholesterol to invade, producing a vicious circle of increasing inflammation. Markers of inflammation in the bloodstream also have been linked to cognitive decline and abnormalities in brain structure. As people age, the regulatory processes that combat inflammation become less effective, resulting in greater inflammatory responses and damage.

Systemic inflammation is associated with a range of chronic diseases that are also related to diet, obesity, and lack of physical activity—notably cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Fat (adipose) tissue is a source of chemicals that promote inflammation. Many risk factors for decline in brain health—including free radicals (countered by antioxidants) and homocysteine (related to B vitamins)—can trigger inflammatory responses in the brain. And so can oxidized lipids, related to unhealthy cholesterol levels.

The best strategy for combating inflammation is to make the healthy lifestyle changes that can reduce your risk of chronic disease. We’ll look at these risk factors in-depth in later chapters (see Box 3-5, “Inflammation”).

Omega-6s and Inflammation

Another common type of fatty acid is called omega-6, found in liquid vegetable oils high in polyunsaturated fats, including corn, safflower, sunflower, and soybean oils, as well as walnuts and soybeans. Linoleic acid (LA) is the essential omega-6 fatty acid, meaning the body can’t produce it but must obtain it from dietary sources; LA is necessary for normal growth, development, and brain function. But you may have seen warnings, on the Internet or in popular nutrition books, about the dangers of omega-6 fatty acids, which supposedly cause inflammation. Some experts have recommended lowering the ratio of omega-6 fats to omega-3 fats to combat this risk.

It’s true that some of the main omega-6 fatty acids are involved in the early stages of inflammation, but they also give rise to anti-inflammatory molecules. A recent American Heart Association review, however, concluded that higher intakes of omega-6s “appear to be safe and may be even more beneficial (as part of a low–saturated-fat, low-cholesterol diet).”

In fact, an analysis published in Circulation found that people who swap 5 percent of the calories they consume from saturated fat sources, such as red meat and butter, with foods containing linoleic acid saw a 9 percent lower risk of coronary heart disease events. Switching from saturated fat to linoleic acid was also associated with a 13 percent lower coronary heart disease mortality risk. Since what’s good for the heart is good for the brain, this suggests there’s no reason to fear omega-6 fats.

Carbs: Fiber, Sugar, and Starch

After the “fat-free” craze, the next target for a healthy-eating fad was carbohydrates. Going “low-carb,” it was claimed, would lead to dramatic weight loss and other health benefits. In extreme forms, this fad meant cutting back even on healthy sources of carbohydrates, such as fruits and vegetables.

Not surprisingly, the reality about the health effects of carbohydrates is more complicated than such fads take into account. Carbohydrates—composed of sugars, starches, and fiber—provide energy for the body, especially the brain and the nervous system. To obtain that energy, enzymes break down carbohydrates into glucose (blood sugar) during digestion, which the body then uses to fuel its many functions.

So, your brain needs some carbohydrates, and it suffers when you don’t get enough. Dietary fiber, a type of carbohydrate that passes through your body undigested, has beneficial effects on your cardiovascular system that can in turn help protect your brain. (When counting “net” carbohydrates, subtract fiber from the total, since it doesn’t get digested like sugar and starch.) Sugar, however, especially in the form of added sugar that comes with no extra vitamins or minerals (versus, for example, the sugar in a piece of fruit), is increasingly seen as a key contributor to chronic disease. And research is beginning to implicate starch, such as that in refined grain products, as an important culprit in weight gain and diabetes.

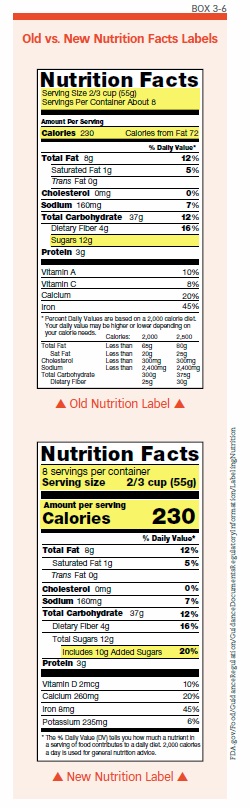

Carbohydrate Math

You can quickly see the fiber and sugar content of foods on the Nutrition Facts panel, and recent pending revisions to the panel include a separate listing of added sugars (see Box 3-6, “Old vs. New Nutrition Facts Labels”). To find the starch content takes just a bit of math: Subtract the fiber and sugar grams from the total grams of carbohydrates. To calculate the starch content of a one-cup serving of corn flakes, for example, subtract the fiber (1) and sugar (3) grams from the total carbohydrates (24): 24-1-3=20 grams of starch (about the same amount as in a cup of potatoes).

Simple vs. Complex

Carbohydrates are also classified as simple or complex—a distinction that confuses many people. Simple carbohydrates are made up of one (single) or two (double) sugar molecules. When most people think of simple carbohydrates, they think of sucrose (a double sugar), the stuff you sprinkle on cereal or spoon into your coffee. But that’s only the most familiar simple carbohydrate. Others include glucose (a single sugar found in most fruits), fructose (a single sugar also found in fruits), galactose (a single sugar found in dairy products), lactose (a double sugar found in dairy products), and maltose (found in certain vegetables and in beer).

The nutritional value of simple carbohydrates depends on the foods in which they are found—they are not necessarily bad for you or to be avoided just because they’re “simple.” The simple sugars, such as those found in candy, non-diet sodas, syrups, and table sugar, provide calories, but few other nutrients. In contrast, intake of nutritious foods, such as fruits, vegetables, milk, and other dairy products, provides not only calories from sugar, but also essential vitamins and minerals.

Starch Cautions

Carbohydrates that have three or more sugars are called complex. These “starchy” carbohydrates are found in foods including beans and other legumes, starchy vegetables (corn, potatoes), and whole-grain breads and cereals. The health impact of complex carbohydrates, again, depends on what else they bring to the table. Legumes, vegetables, and whole grains provide essential nutrients; on the other hand, refined complex carbohydrates, such as white flour, are stripped of many of their original nutrients in processing.

Doubts About the Glycemic Index

One reason starchy foods might contribute to weight gain and diabetes risk is that they tend to have a higher glycemic index (GI), a measure of how quickly your body converts a food to glucose. Low-GI foods are slowly digested and include lentils, soybeans, and many whole grains. In contrast, high-GI foods are converted to glucose more rapidly; these include potatoes and white bread.

When a food’s typical serving size is factored along with its glycemic index, the result is called the glycemic load. Choosing lower-glycemic foods is generally associated with health benefits, including possible reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, though recent research has questioned the cardiovascular benefits of low-GI eating.

The evidence for brain benefits of a low-GI diet is also inconsistent. Some studies have shown benefits, while others failed to find any differences, and still other studies showed effects on only some aspects of cognitive performance.

Moreover, new Tufts research has questioned the utility of commonly used glycemic index values. According to 2016 findings published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, actual blood-sugar effects can vary by an average of 20% within an individual and 25% among individuals. “Glycemic-index values appear to be an unreliable indicator even under highly standardized conditions and are unlikely to be useful in guiding food choices,” says lead study author Nirupa Matthan, PhD, a scientist in the HNRCA Cardiovascular Nutrition Laboratory. “If someone eats the same amount of the same food three times, their blood-glucose response should be similar each time, but that was not observed in our study. A food that is low glycemic index for you one time you eat it could be high the next time, and it may have no impact on blood sugar for me.”

Carbohydrate Conclusions

So what’s the bottom line on carbohydrates and your brain? As with fats, carbohydrates are neither all good nor all bad. Tufts researchers have even found that very low-carbohydrate diets could have a negative impact on thinking and cognition. That’s likely because the brain doesn’t store glucose, its primary fuel, but depends on the body’s production of it from carbohydrates in the diet. After only a day or two, even the glucose stored by the body is exhausted and must be replenished from the diet.

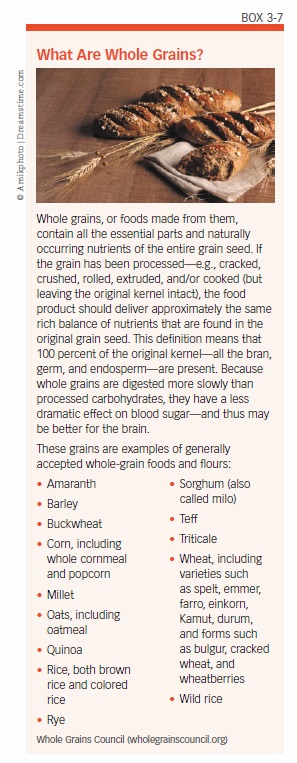

Other research has linked consumption of certain kinds of carbohydrates to possible brain benefits. An 11-year assessment of diet and cognitive function among nearly 4,000 older men and women found: “Whole grains and nuts and legumes were positively associated with higher cognitive functions and may be core neuroprotective foods common to various healthy plant-centered diets around the globe” (See Box 3-7, “What Are Whole Grains?”).

On the other hand, consuming too many carbohydrates relative to protein and fat seems to contribute to cognitive decline. In one study, scientists reported that people 70 and older who ate the highest proportion of carbohydrates were at nearly four times the risk of developing mild cognitive impairment than their counterparts who ate relatively fewer carbohydrates. Risk also rose with a diet heavy in sugar. Study participants who consumed more protein and fat relative to carbohydrates were less likely to become cognitively impaired.

Protein Power

Despite the booming popularity of protein on supermarket shelves, most Americans probably already get plenty of protein—and too many of the calories and saturated fats that accompany animal sources of protein. The Daily Value (DV) for protein used on the Nutrition Facts panel percentages is 50 grams. Most of us far exceed that number, with actual consumption estimated at 62 to 66 grams of protein daily for women and 88 to 92 grams for men (see Box 3-8, “Your Protein Plan”).

The protein equation may be different for older people, however. “It’s estimated that 20 percent of people between the ages of 51 and 70 have an inadequate protein intake,” says Paul Jacques, DSc, director of Tufts’ HNRCA Nutritional Epidemiology Program. Often, older people simply eat less as appetites wane, and that means consuming less protein.

Recent research by Dr. Jacques and colleagues, in fact, found that to get the most out of exercise, older participants also had to be consuming enough protein. Participants who did muscle-strengthening exercises without protein intake of at least 70 grams daily actually had lower muscle mass.

Protein for Breakfast

How much protein you need really depends on your body weight—0.8 grams of protein per 2.2 pounds. For example, a 125-pound woman would need 46 grams of protein per day, while a 175-pound man would need 64 grams per day. If you are very physically active, you may need to increase that. You might also want to spread your protein consumption through the day, rather than concentrating it at dinnertime (see Box 3-9, “Timing Your Protein”).

When you eat your daily protein may be as important as how much you consume, Dr. Jacques adds: “Meeting a protein threshold of approximately 25 to 30 grams per meal represents a promising yet relatively unexplored dietary strategy to help maintain muscle mass and function in older adults.” Breakfast, he says, may provide the greatest opportunity to more evenly distribute the day’s protein.

As you age, protein is essential to prevent the loss of lean muscle mass, called “sarcopenia,” and for the brain. Protein is important to your brain for the production of neurotransmitters and enzymes, and to maintain the structural components of the brain.

So you should aim to consume enough protein from lean, healthy sources to keep your muscles and brain strong, while avoiding the extra calories and saturated fats that accompany less-healthy protein sources.

Balancing Act

The changing recommendations of how best to balance fats, carbohydrates, and proteins in a brain-healthy diet can seem like a roller coaster. That “roller coaster” is best understood as not a circular ride at all, however, but an occasionally winding journey. As science uncovers new evidence, naturally, those dietary recommendations will detour to match. That’s the nature of science and discovery—otherwise, our maps would still warn, “Here there be dragons.”

The best advice is to use your brain—in the form of common sense—to eat right to protect it. Avoid fad diets, quick fixes, and radical swings to extremes, while embracing the healthy choices we’ll explore in-depth in the next chapter.

The post 3. Fundamental Nutrients appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 3. Fundamental Nutrients »

Powered by WPeMatico