2. Patterns For Brain Health

Although certain individual foods have frequently been associated with brain health, as we’ll see in the next chapter, protecting your brain isn’t as simple as eating a few extra blueberries or sipping an occasional cup of green tea. The health of your brain—like your overall health—instead requires a healthy dietary pattern.

Brain Basics

The updated Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs) didn’t recommend a single, one-size-fits-all dietary pattern, although several patterns were cited as healthy examples and are included in this chapter. The DGAs did, however, offer a list of what to look for in a healthy dietary pattern—good advice for lifelong healthy eating, as well as a smart start for eating right for your brain. These principles include consuming:

- A variety of vegetables from all of the subgroups—dark green, red and orange, legumes (beans and peas)

- Fruits, especially whole fruits

- Grains, at least half of which are whole grains

- Fat-free or low-fat dairy, including milk, yogurt, cheese, and/or fortified soy beverages

- A variety of protein foods, including seafood, lean meats and poultry, eggs, legumes (beans and peas), and nuts, seeds, and soy products

- Unsaturated oils

- A healthy eating pattern limits saturated fats and trans fats, added sugars, and sodium

A Blood-Pressure Plan for Brain Health

Among the dietary patterns recommended by the DGAs is one that’s proven to improve blood pressure, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) eating plan, designed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Following a DASH-style pattern seems to also be good for your brain—not surprising, since cardiovascular health is linked to protecting your brain against strokes and dementia. The DASH regimen is high in fruits, vegetables, and grains, while cutting back on meat, saturated fat, sweets, and salt.

The DASH plan was based on clinical studies that tested the effects of sodium and other nutrients on blood pressure. The first DASH study compared three eating plans: a typical American diet, the typical American diet with added fruits and vegetables, and the DASH plan. People who followed the high fruits and vegetables plan had reduced blood pressure, and those who followed the DASH eating plan experienced even greater drops in blood pressure. A second DASH study examined the effects of restricting sodium, comparing diets with sodium levels of 3,300 milligrams (mg), 2,300 mg, and 1,500 mg per day. (The latest dietary guidelines call for a maximum of 2,300 mg daily.) The greatest blood pressure reduction occurred with the DASH plan that was lowest in sodium. Moreover, the DASH eating plan lowered blood pressure more than the typical Western diet at any of the sodium levels.

Subsequent research has shown that even partly adhering to a DASH plan also pays off for cognitive protection. People whose diets most closely adhered to the DASH pattern scored higher on the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (MMMSE), a standard cognitive measurement. Re-tested 11 years later, those in the top DASH group scored even higher compared to those in the group least-adherent to the DASH diet.

The results suggest that including whole grains, vegetables, low-fat dairy foods, and nuts in the diet may offer benefits for cognition in later life, researchers commented. They concluded, “We believe that what we have observed is that the total DASH-like diet is greater than the sum of its parts.”

Mediterranean Diet Plan

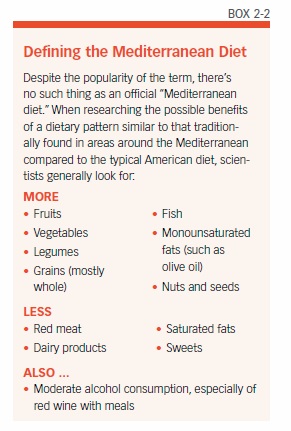

Another heart-healthy dietary pattern that seems to have brain benefits is the “Mediterranean diet” (see “Mediterranean Diet Pyramid,” Box 2-1 and “Defining the Mediterranean Diet,” Box 2-2). Following this traditional dietary pattern typically consumed in Mediterranean countries has been shown to have cardiovascular benefits. But research shows that the Mediterranean diet also seems to be good for your brain.

Most recently, a study published in the journal Neurology reported an association between adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet and brain volume (see “Mediterranean Diet Linked to Bigger Brains,” Box 2-3).

An earlier study published in Neurology reported that sticking to a Mediterranean-style diet, with more fish and less meat, might help keep your brain younger. When cognitively healthy older adults most closely followed a Mediterranean diet, their brains’ aging processes slowed by the equivalent of up to five years. The Columbia University study used MRIs to measure the brains of 674 older adults, average age 80, and compared that data to adherence to a Mediterranean eating pattern as gauged by food questionnaires. Those with scores in the half most closely sticking to the pattern had larger brain volumes. The study assigned points to high intake of vegetables, legumes, fruits, cereals, fish, and monounsaturated fatty acids, such as olive oil; a low intake of saturated fatty acids, dairy products, meat, and poultry; and moderate alcohol consumption. When analyzed separately, higher fish intake, lower meat consumption, and moderate alcohol use were also associated with greater brain volumes.

Adding to the Evidence

Individual studies specifically focused on the Mediterranean diet have also added to this evidence. Data on 17,478 participants in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study, average age 64, revealed that healthy people eating more Mediterranean-style diets were 19 percent less likely to develop cognitive impairment over four years. That meant consuming more fish and plant products while eating less red meat and dairy.

An earlier Columbia University study found that subjects who adhered to a Mediterranean-style eating plan were at lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease. The regimen consisted mostly of vegetables, legumes, fruits, whole-grain cereals, and some fish, and was high in monounsaturated fats and low in saturated fat, meat, and dairy. Even after adjusting for demographics and known risk factors, one-third of the individuals in the study who followed the Mediterranean-style diet most closely had about a 40 percent reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s compared to the group with the lowest adherence. Each additional unit of adherence to a Mediterranean diet (measured on a 0-9 scale) was associated with a nine-to-10 percent reduction in Alzheimer’s risk.

The MIND Diet

While both the DASH eating plan and a Mediterranean-style diet are associated with brain benefits, a hybrid dietary pattern—called the MIND diet—that combines the best of both with the latest cognitive research may protect memory and thinking even better. A study published in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia in September 2015 offered intriguing evidence of a dietary pattern that seems especially well suited to protecting the brain.

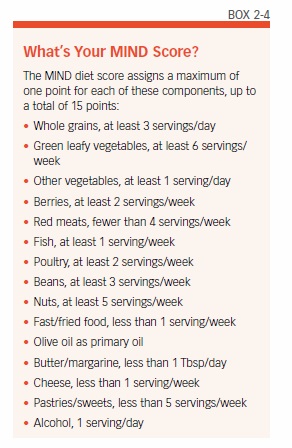

Martha Clare Morris, ScD, of Rush University, and colleagues developed the MIND diet score as a hybrid of the Mediterranean and DASH diets. But it also particularly focuses on “the dietary components and servings linked to neuroprotection and dementia prevention.” Many of these components are foods and nutrients we’ll look at in depth in the next few chapters.

Similar to the Mediterranean and DASH regimens, MIND “emphasizes natural plant-based foods and limited intakes of animal and high saturated-fat foods, but uniquely specifies the consumption of berries and green leafy vegetables.”

Differences and Don’ts

There are some differences, too. The MIND diet doesn’t specify high fruit consumption other than berries. “Blueberries are one of the more potent foods in terms of protecting the brain,” researchers noted, and strawberries have also performed well in past studies of the effect of food on cognitive function.

MIND drops the DASH recommendation for high dairy consumption and calls for only weekly fish consumption, which is lower than recommended in the Mediterranean diet.

The MIND regimen also specifies some dietary don’ts, identifying five unhealthy groups to limit:

- Red meats

- Butter and stick margarine

- Cheese

- Pastries and sweets

- Fried or fast food

The MIND diet includes at least three servings of whole grains, a salad, and one other vegetable every day—along with a glass of wine. It also involves snacking most days on nuts and eating beans every other day or so, poultry and berries at least twice a week, and fish at least once a week. Dieters must limit eating the designated unhealthy foods, especially butter (less than 1 tablespoon a day), cheese, and fried or fast food (less than a serving a week for any of the three), to have a real shot at avoiding the devastating effects of Alzheimer’s, according to the study (see “What’s Your MIND Score?” Box 2-4).

Diets vs. Alzheimer’s

The prospective study used a 144-item food questionnaire to score 923 participants ages 58 to 98, in the Rush Memory and Aging Project, for adherence to each type of diet: MIND, DASH, or Mediterranean-style. Responses were assigned points to score how closely their diets matched each of the three dietary patterns being tested. Participants were initially free of Alzheimer’s disease. They were then followed for an average 4.5 years to track who developed Alzheimer’s disease; during the study, 144 incident cases of Alzheimer’s were diagnosed.

In the study, the MIND diet was associated with a slower rate of cognitive decline—equivalent to 7.5 years of younger age. Those with the highest MIND diet scores were 53 percent less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than those with the lowest scores.

The lower risk for those most closely following the MIND diet was similar to those with the highest adherence to a Mediterranean diet (54 percent) and the DASH plan (39 percent). But only the top one-third of Mediterranean and DASH scores were associated with lower Alzheimer’s risk. The second-highest third of MIND scores were also associated with lower risk (35 percent), however, suggesting that even modest dietary improvements following the MIND pattern could be beneficial.

Although the observational study was not designed to prove cause and effect, Morris and colleagues noted that the results “suggest that even modest adjustments to the diet may help to reduce one’s risk of Alzheimer’s disease. For example, the MIND diet score specifies just two vegetable servings per day, two berry servings per week, and one fish meal per week.” Those recommendations are much lower and easier to achieve than comparable guidelines in the Mediterranean or DASH plans.

Although more research needs to be done, it makes sense that such a dietary pattern might help make a difference for brain health. “Inflammation and oxidative stress play a large role in the development and progression of Alzheimer’s disease,” says Tammy Scott, PhD, a scientist at Tufts’ HNRCA Neuroscience and Aging Laboratory. “The MIND diet particularly emphasizes foods, such as green leafy vegetables, berries, and olive oil, which are rich in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents that may help to protect against dementia and cognitive decline.”

Diet and Aging

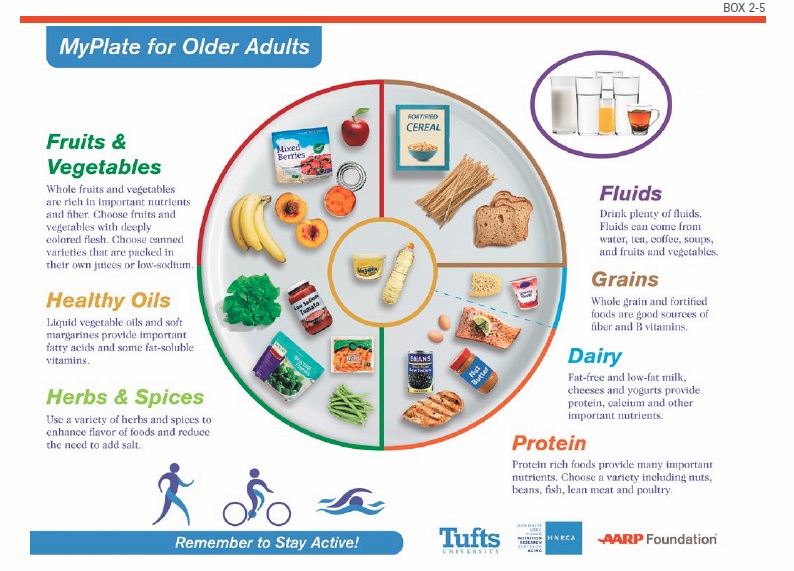

Whether specifically for brain health or overall health, the dietary needs of older adults are differen than those of younger individuals. In March 2016, nutrition scientists at Tufts’ Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging introduced an updated MyPlate for Older Adults (see “MyPlate for Older Adults,” Box 2-5), revised to reflect the latest Dietary Guidelines for Americans. This system calls attention to the unique nutritional and physical activity needs associated with advancing years, emphasizing positive choices. It shows how older adults might follow a healthy dietary pattern that builds on the MyPlate graphic.

One important change as you get older is that your calorie needs typically decrease after age 50; men generally need 2,000 daily calories and women 1,600, depending on physical activity. But your vitamin and mineral requirements stay the same or may even increase—which can make it a challenge to get the nutrients you need from a smaller calorie intake.

So, MyPlate for Older Adults provides examples of foods that contain high levels of vitamins and minerals per serving. These choices are also consistent with the dietary guidelines, which recommend limiting foods high in trans and saturated fats, salt, and added sugars.

Dense with Nutrients

If you’re consuming fewer calories, it’s important to get as many nutrients from those calories as possible. MyPlate for Older Adults spotlights vegetables and fruits as nutrient-dense food choices that are convenient, affordable, and readily available. Half of MyPlate for Older Adults is made up of fruit and vegetable icons, which reflects the importance of eating several servings of fruits and vegetables per day in a range of colors.

Consuming a variety of produce with deep-colored flesh introduces a larger amount of plant-based chemicals, nutrients, and fiber into your diet. MyPlate for Older Adults also includes icons representing frozen, pre-peeled fresh, dried, and certain low-sodium, low-sugar canned options. That’s because fruits and vegetables in those forms contain as many or more nutrients as fresh and they are easier to prepare, are more affordable, and have a longer shelf life—all important considerations for older consumers.

MyPlate for Older Adults also features whole, enriched, and fortified grains because they are high in fiber and other beneficial nutrients. Experts advise making at least half your grain choices whole grains.

Suggested protein sources include fish and lean meat as well as plant-based options, such as beans and tofu. For cooking and serving, the Tufts experts recommend vegetable oils and soft spreads (free of trans fats—check the label) as alternatives to foods high in animal fats because animal-based products, such as butter and lard, are higher in saturated fat.

Other icons represent regular physical activity, emphasize adequate fluid intake, and focus on seasoning with herbs and spices instead of salt.

What to Avoid

Watching sodium intake is important for older people, not only for heart health but also because of the danger high blood pressure presents to the brain. “Blood pressure tends to increase as we age, so it is especially important for older adults to monitor dietary salt and, for most of us, try to find ways to decrease intake,” says Tufts’ Alice Lichtenstein, DSc, director of Tufts’ HNRCA Cardiovascular Nutrition Laboratory. You can also cut down on salt by choosing the low-sodium options of items such as canned vegetables, and draining and rinsing canned beans. Excess sodium intake is only one of the unhealthy habits you should avoid to help protect your aging brain. One 17-year study of more than 5,000 English adults found that those with the unhealthiest behaviors were nearly three times more likely to suffer impairments in thinking and twice as likely to have memory problems as those with the healthiest lifestyles.

The study looked at the associations between cognition and four behaviors known to have negative overall health effects:

- Smoking

- Low fruit and vegetable consumption, defined as eating fewer than two servings of fruits and vegetables per day

- Lack of physical activity

- Alcohol abstinence versus moderate alcohol consumption, defined as drinking between 1 and 14 alcoholic beverages per week.

Compared to those with no unhealthy behaviors, those with three or four bad habits at early midlife were 84 percent more likely to have poor cognitive function 17 years later. As participants got older, the association between unhealthy behaviors and poor cognitive function was even stronger—nearly double.

Skip the Char

Even a habit as seemingly benign as blasting your food with high heat might be bad for your brain. In a study published in 2015 in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, researchers reported that chemicals called advanced glycation end products (AGEs), formed when foods are cooked at high temperatures, may contribute to the risk of developing Alzheimer’s. Scientists used dietary survey data on the consumption of various foods to calculate that diets containing larger quantities of AGEs—especially from meats—correlated with higher incidence of Alzheimer’s.

The study could only estimate AGE content, however, based on typical food preparations and the tendency of AGEs to form in certain foods. Researchers cautioned that other mechanisms could be responsible for the association, such as the fact that meat is also a source of saturated fat, which contributes to unhealthy cholesterol levels. To be on the safe side, turn down the temperature, avoid charring, and opt more often for braising meats in liquid.

Watch Your Weight

Being overweight or obese, not surprisingly, is another danger to your brain. A growing body of research links excess weight—also an important risk factor for heart disease—to cognitive decline and dementia.

To determine whether you’re at risk, you can calculate your body mass index (BMI); this common measure compares your weight to your height. Some research has shown that the ratio of your waist to your hip measurement may be a more accurate measure of cardiovascular risk, although this hasn’t been well tested for similar cognitive risks. Simply measuring your waistline, as if choosing the right pants size, also is a good general rule suggested by the American Heart Association and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Men should aim for a waist size less than 40 inches; women, less than 35 inches.

Brain Gains from Losing Weight

On the other hand, losing weight—especially combined with additional exercise—can benefit your brain. One study tested the cognitive benefits of a weight-loss diet, an exercise program, and dieting plus exercise among 107 frail, obese older adults for one year. Compared to a control group, all three regimens generally improved cognitive performance, though results varied by test.

But the combination of diet plus exercise was associated with the greatest improvement in MMMSE scores, word-fluency testing, and two “trail-making” tests of visual attention and task switching. Exercise alone boosted MMMSE and word fluency scores about the same as when combined with dieting.

Calorie Restriction

Several studies have reported that actively cutting down on calories—not simply “watching your weight”—might also be an effective strategy against cognitive decline. One German study found a connection between a restricted-calorie diet and improved memory among participants divided into three groups: One aimed to reduce calorie intake by 30 percent, mostly by eating smaller portions; a second group kept calories the same while increasing intake of healthy fats by 20 percent; and a third, the control group, made no dietary changes. At the end of three months, the calorie-cutting group scored an average of 20 percent better in tests of memory performance; the other groups showed no change. Researchers theorized that the calorie-cutters, who lost four to seven pounds, might experience brain benefits from decreased insulin and inflammation.

In another study, researchers compared the calorie intakes of older people suffering mild cognitive impairment (MCI) with normal control subjects. Those consuming the most calories—more than 2,143 per day—were almost twice as likely to have MCI than participants eating the least, fewer than 1,526 daily calories. The higher the amount of calories consumed each day, the higher the risk of MCI. The results were the same after adjusting for history of stroke, diabetes, amount of education, and other factors that can affect risk of memory loss.

Blood Sugar Risks

Being overweight or obese also affects your blood sugar levels, increasing the risk of diabetes. Chronically high blood-glucose (sugar) levels, whether from insulin resistance, prediabetes, or type 2 diabetes, seem in turn to affect the brain. One study linked higher blood glucose levels with a 40 percent greater risk of developing dementia. Blood glucose levels of diabetics who developed dementia over seven years averaged 190 mg/dl, compared to 160 mg/dl in those who did not develop dementia. (Normal fasting glucose levels are below 100 mg/dl and levels above 126 mg/dl are considered diabetes.)

People whose blood glucose is higher than normal but not high enough to meet the criteria for diabetes are also at greater risk. That same study found that people with the highest levels—but short of diabetes—were 20 percent more likely to develop dementia than those with normal blood-glucose levels. Among non-diabetic participants, those who developed dementia had blood-sugar levels averaging 115 mg/dl, compared with 109 mg/dl for those who did not develop dementia.

Hold the Starch

Smart choices about carbohydrates—another aspect of a healthy dietary pattern—can reduce your diabetes risk and help control your blood sugar. Recently, a large observational study linked starch consumption to greater risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Foods with a higher ratio of starch to fiber include processed and refined grain products, such as white rice, crackers, many ready-to-eat breakfast cereals, and bread and pasta that’s not made from whole grains. Some vegetables, such as white potatoes and corn, are also high in starch. Intakes of total fiber, cereal fiber, and fruit fiber were all associated with lower diabetes risk.

The post 2. Patterns For Brain Health appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 2. Patterns For Brain Health »

Powered by WPeMatico