3. The Power of Vegetables

Potent Phytonutrients

Your mother was right to tell you to eat your vegetables when you were a child—and that’s still good advice for adults, regardless of your age. On the Tufts’ MyPlate for Older Adults, vegetables occupy more space than any other food group for several healthful reasons.

Some of the health benefits of vegetables (as well as fruits) can be attributed to natural plant compounds called phytonutrients (also referred to as “phytochemicals”). This term comes from the Greek word for “plant.” In nature, plants use these compounds—often found in the highest amounts in their outer surfaces or peels—as pigments and as defenses against bugs, fungi, and infections (see Box 3-1, “Pigment in Plants May Fight Lung Cancer”).

According to Diane L. McKay, PhD, faculty expert for this report and a scientist in Tufts’ HNRCA Antioxidants Laboratory, “These are not classic nutrients like vitamins. These are compounds present in plants that several studies have shown have biological activity that confers health benefits, such as improving markers of chronic disease risk.

“Nearly all phytonutrients have antioxidant activity,” she explains, “but that is not necessarily their mode of action in the body. Within cells, they may turn signals on or off, affect inflammation, or trigger a whole cascade of events.”

Types of phytonutrients include carotenoids (found in carrots, winter squash, tomatoes, and yellow peppers), organosulfides (found in onions, garlic, broccoli, and cabbage), and phytosterols (found in peas, soybeans, and vegetable oils). “There are thousands of different phytonutrients that have been identified to date, and we’re still going,” Dr. McKay says.

Eat a Variety of Veggies

That phytonutrient variety is one reason to consume a wide

mix of plant foods in your diet. “Each provides a different array of phytonutrients. You never really eat just a single phytonutrient in

a food,” Dr. McKay says. “And you might not want to, since they

work synergistically.”

What about so-called “superfoods” in the produce aisle? “They’re all super!” Dr. McKay insists. “Eating a variety of vegetables and other healthy foods is the basis of a good diet. There isn’t any one whole food that will meet all of your nutrition requirements.”

In all of the various rating systems for foods, she adds, certain groups of foods always come out on top—those that are plant-based. Part of this is because of plants’ phytonutrient riches. Vegetables are also excellent sources of fiber, as well as many of the nutrients you may need more of as you age. The health benefits are clear: People who consume more plant-based foods have a lower risk of cardiovascular disease and certain cancers.

There are no minimum daily requirements for the more than 25,000 phytonutrients that science has identified in plants. These compounds are not essential to keeping you alive the way that, say, protein or vitamins are. Many of the health benefits of phytonutrients, which are also found in tea, coffee, cocoa, whole grains, and fruits, are still being studied.

Phytonutrients also work together to produce greater benefits than would occur if you were to combine the individual nutrients. This is one reason why nutrition experts advise getting nutrients from whole foods rather than supplements; the many nutrients present in whole foods produce an effect greater than any effect produced by nutrients in supplement form.

Vegetarians and Semi-Vegetarians

You don’t have to become a vegetarian to improve your diet, but studies of vegetarians provide convincing evidence of the health benefits of eating more plant-based foods. In one such study, vegetarians were 32 percent less likely to suffer ischemic heart disease (also called coronary artery disease) than non-vegetarians. The benefits were seen in participants who had been following a vegetarian diet for less than five years, as well as in long-term vegetarians.

Other research has found that vegetarians tend to be at lower risk for heart disease, certain cancers, diabetes, obesity, and hypertension.

Pescatarian Benefits

Some research suggests that a pescatarian diet—one that includes fish as well as an abundance of plant foods—might be even more healthful than a strictly vegetarian regimen. One report showed that people who are otherwise vegetarians but also eat fish at least once a month were at the lowest risk of colorectal cancers. Adding fish to a vegetarian diet was associated with less risk than any other type of vegetarian diet, including a vegan regimen.

“This was a well-constructed study that confirms the idea that a plant-based diet conveys significant protection against colorectal cancers,” says Joel B. Mason, MD, Tufts professor of medicine and nutrition. “Prior studies had also suggested that consumption of fish did not increase the risk for the cancer, but this study goes one step further and suggests fish consumption might convey additional protection beyond what a plant-based diet alone provides.”

Plant Power

The Adventist Health Study, which focuses on members of the Seventh-Day Adventists, is an ongoing research project at Loma Linda University in California. The researchers have previously reported that vegetarians tend to be at lower risk not only for certain cancers but also for heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and hypertension. Because the Adventist religion has historically advocated vegetarianism, the study offers an unusual opportunity to compare the health effects of meat avoidance in a large population.

The latest findings from the study addressed diet and colorectal cancer risk among 77,659 participants over an average of 7.3 years. During that span, researchers recorded 490 cases of colorectal cancers. Overall, vegetarians of all types were at 22 percent lower risk than non-vegetarians. But, the researchers went further and looked at cancer risks among differing degrees of vegetarianism.

The scientists who analyzed the data said they were surprised at the variation that was found among vegetarian lifestyles. Compared to non-vegetarian participants, pescatarians were 43 percent less likely to develop such cancer. That risk was significantly lower even than vegans (16 percent lower than non-vegetarians), lacto-ovo vegetarians, who include dairy and eggs in their diets (18 percent lower), and semi-vegetarians, defined for this study as eating meat or fish once a week (8 percent lower).

The apparent benefits of vegetarian and pescatarian diets are probably understated by the findings, according to lead author Michael J. Orlich, MD, PhD. “It’s worth pointing out that our non-vegetarians are still a relatively low meat-consuming group,” he said. “They average about 2 ounces of meat a day, so we are comparing vegetarians with a pretty low meat-consuming group, and a relatively healthy group overall.”

In fact, Dr. Orlich added, after adjusting for age, race and sex, the rate of colorectal cancer among the nonvegetarians was 27 percent lower than you would expect for an age-, sex- and race-matched population in the US. “If we were to compare our vegetarians with a more average population, the effects might even look stronger.”

Vegetarian Plus

It’s not surprising that a pescatarian diet might offer health benefits. Consuming any mostly vegetarian diet naturally means you’ll consume more vegetables, as well as fruits and grains (hopefully healthy whole grains), than most people. These non-meat foods are packed with nutrients and fiber.

Other studies have also shown numerous health benefits from fish consumption, so it makes sense that adding the occasional seafood meal to a mostly vegetarian regimen could have further benefits. In particular, fatty varieties of fish such as salmon, trout, sardines, some types of tuna, and herring are rich sources of omega-3 fatty acids, which are believed to have cardiovascular benefits as well as possible brain benefits.

Adding fish to your diet can also make it easier to stick to an otherwise mostly vegetarian regimen. And, eating some fish can help prevent nutrient shortfalls common to vegetarian diets, since fish provide protein, zinc, iron, vitamin B-12, and vitamin D, as well as those omega-3 fats. Even if you don’t consume dairy, eating small fish with bones, such as sardines, or fish canned with bones, such as salmon, can boost your intake of calcium.

A pescatarian diet is also similar in some ways to the Mediterranean diet, with its emphasis on eating lots of produce, healthy unsaturated fats, legumes, and seafood.

Pescatarian diets tend to be naturally lower in calories, which can help you lose weight. The lower body mass index (BMI) of vegetarians and pescatarians likely contributes to their lower risk of heart disease and diabetes.

However, be aware that avoiding meat is neither necessary nor a guarantee of a healthy diet. “Fries and a Coke are vegetarian,” says Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, DrPH, dean of Tufts’ Friedman School. “More important than what you avoid is what you actually eat. The healthiest diets are rich in fruits, nuts, fish, vegetables, yogurt, beans, vegetable oils, and whole grains. Being or not being a vegetarian does not add much to that.”

Buying and Using Veggies

Whether you’re becoming some form of vegetarian or simply trying to add more veggies to your diet, the MyPlate program serves up this advice on selecting and using vegetables:

- Buy fresh vegetables in season. They cost less and are likely to be at their peak flavor.

- Stock up on frozen vegetables for quick and easy cooking in the microwave.

- Buy vegetables that are easy to prepare. Pick up pre-washed bags of salad greens and add cucumber slices and grape tomatoes for a salad that’s ready in minutes. Buy packages of veggies such as baby carrots or celery sticks for quick snacks.

- Use a microwave to quickly “zap” vegetables. (Note that microwaving, much like steaming, preserves more of the nutrients in vegetables than boiling.)

- Sauces or seasonings can add calories, saturated fat, and sodium to vegetables. Use the Nutrition Facts label to check the calories, saturated fat, and sodium in packaged vegetables.

- Buy canned vegetables labeled “reduced sodium,” “low sodium,” or “no salt added.”

In the rest of this chapter, we spotlight examples of vegetables that are excellent choices for helping meet your nutritional needs as you age, including tips on how to store and serve them. (We also cover foods such as avocados and tomatoes that are botanically classified as fruits but are typically sold and prepared like vegetables. Beans and other legumes will be covered in the chapter on protein foods.) We’ve also included some less-familiar options such as fennel and celeriac to help you broaden your veggie repertoire. Keep in mind that these are just a few examples of the many healthy choices available to you.

Artichokes

Artichokes might seem a surprising choice to lead off this list, since they’re not ordinarily perceived as a “health food.” But artichokes are rich in minerals, including potassium, calcium, iron, and magnesium, which are important for bone and cardiovascular health, as well as vitamin C and folate. Artichokes are also high in fiber, especially in the soluble fiber that’s been shown to improve cholesterol levels, and they are a low-glycemic-index food that won’t boost your blood sugar too rapidly.

Select artichokes that are compact and heavy for their size, with tight leaves. To loosen the leaves of a mature artichoke, cut off the top one-third and remove the tough outer leaves by hand, then simmer in boiling water with a little lemon juice. The bases of each leaf can be eaten along with the delicate artichoke heart. Cook only in a non-reactive pan such as stainless steel, enamel, or glass, because cast-iron, copper, or aluminum cookware will cause artichokes to discolor (as can carbon-steel knives).

Asparagus

Asparagus is a good source of several B vitamins, including thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, B6, and especially folate. It also provides iron, potassium, and vitamin C, and it’s low in calories and contains just a trace of fat. Asparagus contains more vitamin E than most vegetables, and it’s high in dietary fiber, including a type of soluble fiber that acts as a “prebiotic,” which stimulates the growth of healthy bacteria in the gut.

The only potential downside to asparagus is that it’s high in purines, which some experts advise gout sufferers to avoid because these compounds are thought to raise uric-acid levels. Asparagus is often thought of as a spring delicacy since it is one of the crops harvested earliest in the year (beginning in February) in the U.S., but asparagus can now be found in supermarkets year-round due to imports from Central and South America.

Look for spears that are firm yet tender, with closed, compact, deeply colored tips. Thin spears aren’t necessarily more tender; those at least a half-inch in diameter at the base are best. Store in the refrigerator, as asparagus quickly loses its quality and vitamin C content at room temperature. To extend shelf life, place the asparagus, tips pointing up, in a jar or container filled with about an inch of water, and replace the water when it becomes cloudy.

Avocados

It’s not just a growing taste for guacamole that’s pushing avocados to record popularity: Consumers are becoming increasingly aware that some fats are healthy. Of the 18.6 grams of fat in a typical avocado, only 2.9 grams are unhealthy saturated fat; the rest is heart-healthy unsaturated fat, primarily in the form of monounsaturated fat (13.3 grams). Think of the fats in this healthy fruit (avocados are technically a fruit) as similar to those in olives (also botanically a fruit).

Research suggests that the unsaturated fats in avocados may have cardiovascular benefits. In one comparison study, a moderate-fat diet that included one avocado a day lowered LDL (“bad”) cholesterol more than two other regimens: LDL dropped 13.5 mg/dL on the diet that included avocados, compared to a drop of 8.3 mg/dL on a moderate-fat diet without avocados and a drop of 7.4 mg/dL on a low-fat diet.

Avocados are also good sources of several B vitamins, dietary fiber, potassium, copper, carotenoids, and vitamins C, E, and K. However, consume avocados in moderation—one cup of avocado slices contains 230 calories, a much higher calorie count than most other vegetables.

Adding an avocado to other vegetables, such as the leafy greens in a salad, can also help you absorb carotenoid compounds such as beta-carotene. One study found that topping salads with avocado boosted carotenoid absorption by three to five times.

Research indicates that avocados may also be beneficial for your joints. Avocados contain compounds called unsaponifiables (ASUs), and ASUs derived from avocado and soybean oils are being tested as a treatment for osteoarthritis. One study found that avocado-soybean ASUs improved symptoms of hip and knee arthritis and reduced the need for anti-inflammatory drugs, and another study reported that ASUs significantly reduced the progression of hip arthritis over a three-year period.

Like bananas, avocados will ripen at room temperature after purchase, so you can choose less-ripe fruit that is firmer and less likely to be bruised. Ripe avocados can be kept in the refrigerator for up to a week. Peel avocados carefully, since the greatest concentration of carotenoid compounds is in the dark-green flesh immediately under the skin.

Beets

Fresh beets begin arriving in markets in early summer. Nutrients are generally highest in the familiar purple-red varieties, including phytonutrients called betalains that give beets their vivid color (but which are lost with longer cooking times). Beets are also a good source of fiber, vitamin C, potassium, folate, and iron. Although high in sugar (hence their use in sugar production), beets are low in calories.

Smaller beets are more tender, less woody, and cook faster; select those that are unblemished, hard, and evenly round. Don’t wash beets before storing, though you may want to trim most of the greens to reduce moisture loss. (If you also eat the greens, they are high in lutein and zeaxanthin, phytonutrients that play an important role in eye health.) Peel only after cooking to keep beets’ rich red color from bleeding out.

Broccoli

Broccoli begins to return to farmers’ markets as summer starts to warm up and is available in supermarkets throughout the year. The prototypical healthy veggie, broccoli is indeed a good source of nutrients, including fiber, vitamin C, calcium, folate, riboflavin, potassium, and iron. It’s also high in beta-carotene and other carotenoids, such as lutein and zeaxanthin, that help protect eye health. Phytonutrients found in broccoli, such as indole and isothiocyanates (which contain the compound sulforaphane), have been studied for anti-cancer benefits. The leaves and stalks of broccoli are packed with nutrients, too, though the florets are generally the most nutrition-rich.

One study found that people who ate cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli at least weekly had a 72 percent lower risk of lung cancer than those who seldom ate them. Another study showed that nonsmokers who ate three or more monthly servings of raw cruciferous vegetables had a 73 percent reduced risk of bladder cancer than those who ate the fewest cruciferous foods.

Look for tightly closed, dark-green, or purplish-green florets (indicating more beta-carotene and vitamin C) with tender stalks; avoid yellowing florets that are past their prime. Broccoli can be eaten raw, which retains more vitamin C, but cooking releases more carotenoids for absorption by the body.

Brussels Sprouts

Brussels sprouts are high in potassium and also provide thiamin, riboflavin, vitamin B6, antioxidant flavonoids, and potentially cancer-fighting phytonutrients. Pick bright-green sprouts with no cabbage-y odor; smaller sprouts are more tender and less likely to have the bitterness that makes people think they dislike Brussels sprouts. Steam Brussels sprouts, braise them in a flavorful liquid such as stock, or toss them with olive oil and roast them in the oven.

Cabbage

A cruciferous cousin of broccoli, cabbage shares many of broccoli’s nutritional benefits. All three common varieties of cabbage—red, green, and Savoy—are good sources of potentially cancer-fighting phytonutrients, along with fiber and folate. As you might guess, red cabbage is higher in vitamin C, but Savoy cabbage contains more beta-carotene.

Select heavy, solid heads of cabbage with only a few outer wrapper leaves, which should be clean and undamaged. Hold off washing cabbage until you’re ready to serve it, and don’t cut with a carbon-steel knife to avoid discoloration. If you’re cooking red cabbage, use nonreactive cookware to preserve the color.

Carrots

You probably think of carrots as veggies for your eyes, but researchers have found that these familiar vegetables may also reduce your risk of chronic disease. In one medium carrot, for just 25 calories, you get 1.7 grams of fiber, 195 milligrams of potassium, 3.6 milligrams of vitamin C, and smaller amounts of calcium, zinc, and magnesium. The fiber in carrots includes pectin, which may have cholesterol-lowering properties.

Carrots are best known as a good source of vitamin A, mostly in the form of beta-carotene. A single medium carrot delivers almost twice the recommended daily value of vitamin A, which is associated with carrots’ most celebrated health benefit—protecting your vision. One study found that women who ate more carrots had lower rates of glaucoma, and animal studies have linked nutrients in carrots to a reduced risk of cataracts. Alpha- and beta-carotene may also help protect against cancer (see Box 3-2, “Cancer Protection from Produce”).

Phytonutrients found in carrots called polyacetylenes, including the compounds falcarinol and falcarindiol, have attracted scientific interest for possible cardiovascular benefits. These compounds are thought to have anti-inflammatory properties and to keep blood cells from clumping together. Other studies are investigating these compounds’ ability to inhibit the growth of cancer cells.

Choose brightly colored carrots that are smooth, firm, and relatively straight. Contrary to what you might expect, larger carrots are sweeter, as they’ve had more time to develop natural sugars. If tops are attached, look for bright, feathery, unwilted greens; remove the tops when you get home, as they will extract moisture and nutrients from the carrot roots.

Store carrots in the coolest part of the refrigerator for about two weeks, wrapped in a damp paper towel and placed in an airtight container or bag. Keep carrots away from foods such as apples, pears, or potatoes that release ethylene gas—the gas will cause the carrots to become bitter and to spoil more quickly. Wash carrots thoroughly before using.

If you buy organic carrots, it’s not necessary to peel them, and some studies have found that the peel is richest in nutrients. A few tests have also suggested that cutting or chopping carrots after cooking, rather than before, preserves more nutrients. While cooking destroys some heat-sensitive nutrients, such as vitamin C, it helps make others more readily absorbed by the body. Steaming or microwaving carrots, rather than boiling them, results in less nutrient loss. Roasting carrots brings out their natural sweetness.

Cauliflower

Not all cruciferous veggies are green; another mainstay of the cruciferous family is cauliflower. One cup of cooked cauliflower contains 3 grams of fiber and 2 grams of protein, as well as vitamin C, folate, vitamin B6, and potassium.

Cauliflower comes in the traditional white as well as purple, an antioxidant-rich variety that turns green when cooked, and orange, which adds vitamin A to the equation and tastes more like squash. Look for cauliflower that’s firm and free of bruises and spots, with compact florets; any leaves should be crisp and green.

If you boil cauliflower in water, be gentle: Heat diminishes its vitamin C content, and its B vitamins leach into the cooking water. Roasting, although hard on vitamin C, brings out an earthy sweetness that may appeal to people who think they don’t like cauliflower. Cooked, mashed cauliflower can be served in place of mashed potatoes or combined with them to lower the carbohydrate and calorie count. And, skip the cheese sauce, which adds enough calories and saturated fat to outweigh cauliflower’s nutritional benefits.

Celeriac

To someone unfamiliar with celeriac, the first reaction to this root vegetable, also known as celery root, may be, “You want me to eat what?” The appearance of the knobby ball of roots and flesh can make one wonder how it ever became part of any edible table fare. However, celeriac has a subtler flavor than celery and has a consistency somewhat similar to a potato. Celeriac can be peeled, grated, and used raw in salads, or cooked and mashed along with potatoes. A half-cup serving yields only 21 calories and has plenty of vitamin K and potassium.

Collard Greens

Less familiar to many Americans than other dark leafy greens such as spinach or kale, collards share those greens’ nutritional bang for the buck. Collards and their cousins, such as turnip and mustard greens, belong to the cruciferous-vegetable family, like broccoli and cabbage. Collard greens are a source of beta-carotene, vitamin C, folate, iron, and calcium (one of the best sources among dark leafy greens), along with fiber.

Pick greens that have been kept cool, as they wilt quickly, and choose smaller, tender leaves with fresh green color and no signs of yellowing or browning. If you’re concerned about pesticide exposure, collards are a good choice to go organic. At home, wrap collards unwashed in damp paper towels and keep in the crisper. Wash thoroughly right before using and discard stems and tough leaves. Try using collards in recipes that call for cooked spinach, or add to whole grains.

Fennel

This less-familiar veggie is a flowering plant related to the carrot family. One half of a bulb is a mere 36 calories and provides vitamins A, C, and K, phytonutrients called carotenoids (beta carotene, lutein, and zeaxanthin), and potassium. It is also a good source of fiber. While fennel is commonly used in Italian and French cooking, it is often misunderstood and neglected in the U.S. Is it a vegetable, an herb, or a spice? The hollow stalks of fennel are considered an herb, having an appearance similar to dill. They’re usually chopped and sautéed, and then added to salads, soups, or vegetables. The part of fennel most commonly used in cooking is the cultivated bulb, called the “Florence fennel.” Its inflated leaf base has a mild anise flavor with a sweeter taste. Sliced Florence fennel can be grilled, roasted, or baked.

Jerusalem Artichoke

Contrary to its name, this root vegetable was discovered in North America, where explorer Samuel de Champlain came across it and described its flavor as similar to that of an artichoke. The “Jerusalem” part of its moniker may have come from girasole, the Italian word for sunflower, since this plant is the tuber of a sunflower. Also known as sunchoke, this low-calorie food (55 calories for a half-cup) has piqued the interest of health professionals because it contains inulin, a starchy compound classified as a prebiotic because it supports the growth of beneficial bacteria in the intestines. Sunchokes are slightly sweet and are often served in stir-fried dishes or chopped raw in salads.

Kale

The cruciferous family also includes kale, which may well be the “it” vegetable of the moment, celebrated in everything from cooking magazines to health websites. But, unlike some food fads, this nutritious, leafy green deserves the attention it’s suddenly getting: With a mere 36 calories, one cup of cooked kale delivers 5 grams of fiber and more than 100 percent of your daily vitamin A, as well as vitamins C and K, magnesium, calcium, and potassium. It’s packed with at least 45 antioxidant flavonoids. Like its cruciferous-vegetable kin, it contains glucosinolates—sulfur compounds associated with a reduced risk of cancer.

The fiber in kale is good for your digestive system, and it also benefits your arteries. Research has shown that fiber-related nutrients in kale help the liver and intestines bind cholesterol and carry it out of the body. Although raw kale can help lower cholesterol, kale is especially effective when it’s been steamed for five minutes.

Kale is typically available year-round. You’ll find three common varieties:

- Curly kale, with ruffled, deep-green leaves and a pungent, bitter, peppery flavor.

- Dinosaur kale, also called Tuscan or Lacinato kale, with textured, dark blue-green leaves and a sweeter, more delicate flavor that kale newcomers might prefer.

- Ornamental kale, which is edible despite its name, is also called salad savoy. Its leaves may be purple, pink, red, yellow, cream, and/or green, and it has a mild flavor and tender texture.

Select firm, deeply colored leaves with sturdy stems, free of wilting or discolored spots; smaller leaves tend to be milder in flavor. The Environmental Working Group rates kale as one of the vegetables most prone to pesticide residue, so you may want to consider buying organic. Store unwashed kale in a zip-top plastic bag in the refrigerator and use within five days, as kale’s nutrient content declines rapidly (see Box 3-3, “10 Ways to Use Kale”).

Kohlrabi

This root vegetable tastes similar to a broccoli stem or cabbage heart, but it’s milder and sweeter. It can be consumed raw in salads and slaws or cooked. Kohlrabi is often found in German dishes as well as Kashmiri cuisine. It is an extraordinarily rich source of vitamin C, with one serving providing 100 percent of the recommended daily value.

Lettuce and Salad Greens

Generally, the darker the greens or lettuce, the higher the overall nutritional content—especially levels of beta-carotene. All salad greens are a source of vitamin C, folate, calcium, iron, and other nutrients, though amounts vary widely by type—another argument for consuming a variety.

Deeply-colored greens are higher in vitamins A, C, and K, beta-carotene, the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin, calcium, folate, and fiber than iceberg lettuce. Green and red leaf lettuce, for example, contain nearly 15 times as much vitamin A as iceberg lettuce, 6 times the vitamin K, almost 20 times the beta-carotene, and 6 times the lutein and zeaxanthin. Other popular varieties, such as Romaine, Bibb, and Boston lettuce, outshine iceberg almost as much and exceed leaf lettuce in some nutrients. Broadening your selection even further and including greens such as radicchio and arugula can turn your salads into nutritional stars.

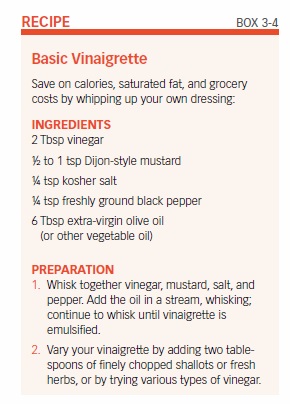

Choose the crispest salad greens you can find; in prepackaged mixes, check the sides and bottom of the container or bag for any signs of wilting, sliminess, or browning. Wrap loose salad greens in a damp paper towel and store in the refrigerator crisper, away from fruits such as apples or ripe bananas that give off ethylene gas. Remember that even the healthiest salad can be made less healthy by slathering on dressings and other toppings high in calories and saturated fat, such as cheese and bacon. For healthier homemade dressing, try a simple recipe of whisking together one part vinegar to two parts oil, with a dash of mustard to emulsify (see Box 3-4, “Basic Vinaigrette”).

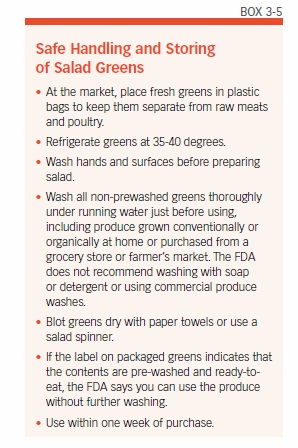

Keep in mind that salad greens of all sorts are prime targets for contamination, so exercise caution in cleaning and handling (see Box 3-5, “Safe Handling and Storing of Salad Greens”).

Okra

Okra, a member of the hollyhock family, is technically a fruit. Its drought-resistant properties make it an attractive food in countries all over the world. Okra grows wild in Africa, Asia, and Australia, and it’s a popular thickening ingredient in gumbo stew. If you find the gooey liquid emitted during cooking unappetizing, cook the okra separately over high heat and then add it to the dish. This low-calorie food (19 calories for eight pods) adds flavor to any meal, as well as vitamins A and K, lutein, calcium, and potassium.

Onions

Onions are members of the allium family and are related to garlic, which has been more extensively studied for health benefits in humans. Onions are a good source of vitamin C, potassium, and dietary fiber. They are also among the richest sources of quercetin, a phytonutrient with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory benefits.

Organosulfur compounds in onions are released by cutting or crushing; in garlic, these compounds have been associated with cancer protection, improved cholesterol levels, and decreased stiffness in blood vessels. It may be that allowing onions to sit for a few minutes after cutting, prior to cooking, helps preserve these beneficial compounds, as has been demonstrated in garlic.

Research has shown that the more pungent, stronger-smelling onions, which are highest in sulfur compounds, exhibit anti-platelet activity. Scientists suggest that eating onions might help prevent platelet aggregation, which may reduce the risk of atherosclerosis, stroke, and heart attack. Generally, yellow and red onions are highest in beneficial compounds, while milder (sweet or Vidalia) varieties are lowest.

Those sulfur compounds, as well as quercetin, may be responsible for onions’ apparent cancer-protective effects. Moderate onion consumption has been associated with a lower risk of colorectal, laryngeal, and ovarian cancers, and daily onion intake has been linked to a reduced incidence of esophageal and oral cancers.

When selecting dry bulb onions, look for those that are firm and have little or no smell. Avoid any with cuts, bruises, or blemishes. Onions are among the produce least prone to pesticide contamination, so choosing organic is optional.

Store unpeeled onions in a cool, dry, dark place to better preserve their antioxidant compounds. Peel your onions carefully, as the phytonutrients tend to be more highly concentrated in the outer layers; don’t “overpeel” and lose these healthy compounds.

Parsnips

The parsnip is a root vegetable with a culinary history dating back to the ancient Greeks and Romans, who cultivated it. The parsnip can be eaten raw, but is usually cooked—it becomes sweeter that way. In either case, parsnips are a good source of fiber and vitamin C and contain more potassium than many other vegetables.

Peas

Green peas provide folate, vitamins A, B3, and C, and lutein and zeaxanthin for your eyes. Peas are members of the legume family (which also includes beans and lentils), so they are higher in protein than most green vegetables. Their fiber includes pectin, which may aid in combatting unhealthy cholesterol. Nutrition numbers vary by type, with green peas higher in B vitamins and zinc, while snow peas stand out for vitamin C and folate. Snow peas are also lower in protein and calories than green peas.

When buying peas still in the pod, look for firm, glossy, medium-sized pods. Keep fresh peas refrigerated, as their sugars rapidly turn to starch at room temperature, and rinse thoroughly before using. Young green peas can be eaten raw along with the pods, as can snow peas and sugar snap peas.

Snap Beans

These edible-pod beans, a favorite with gardeners, are most commonly seen as green beans or yellow wax beans; both are actually immature forms of kidney beans. Formerly known as “string beans,” snap beans have now been bred to grow mostly without the tough “string” down the pod’s seam. Nutritionally, green beans and yellow wax beans are similar except that the latter contain less beta-carotene. Snap beans are good sources of dietary fiber, potassium, vitamin C, folate, and iron.

Look for crisp, not stiff, pods of uniform size for even cooking. Trim the ends before cooking, but resist the temptation to slice them lengthwise (“French style”), which allows flavor and nutrients to leach out of beans during cooking.

Spinach

Popeye was right about spinach: This nutritional powerhouse has been linked to health benefits ranging from boosting muscle strength to reducing diabetes risk to protecting against cataracts. Spinach is rich in carotenoids and vitamin K. It’s also a good source of vitamins C and E, B vitamins including folate, calcium, potassium, and magnesium.

Though spinach is famously high in iron, the oxalates also found in these nutritious greens interfere with the absorption of iron as well as calcium. That high oxalate content also means people at risk for the most common type of kidney stones, calcium oxalate stones, may need to limit their spinach consumption. Patients on blood-thinning medications such as warfarin should also check with their physicians about consumption of leafy greens, such as spinach and kale, which are high in vitamin K, a vitamin that can counteract the effects of warfarin. This isn’t to say that people taking warfarin should avoid foods containing vitamin K; rather, they should aim to consume about the same amount of vitamin K daily.

Buy smaller, vividly green, sweet-smelling leaves with no signs of yellowing and thinner stems. If you’re worried about pesticides, spinach is another smart choice for spending a little extra on organic. Spinach, especially loose-leaf, requires rigorous rinsing to remove grit; dry in a salad spinner unless you plan to cook the spinach, which can be cooked damp. Because carotene compounds are fat-soluble, you’ll get the most from your spinach when it’s combined with a little heart-healthy unsaturated vegetable oil; cooking will also release more of these compounds.

Summer Squash

Though varied in appearance, color, and nutritional values, summer squash are all gourds—relatives of melons and cucumbers. Unlike their harder-rind winter cousins, summer squash, including zucchini and crookneck or yellow squash, are picked while still immature. Summer squash have a high water content, which has the advantage of keeping calories low. Summer squash deliver fiber, magnesium, potassium, and vitamins A and C. The green rind of zucchini is packed with eye-protecting lutein and zeaxanthin; you have to eat the rinds of summer squash to get these and other carotene compounds.

Sweet Potatoes

Sweet potatoes can be found in a range of colors, from pale orange to deep red and purple. At 180 calories per one cup of cooked sweet potato and an average cost of around $1 per pound, sweet potatoes won’t break the scales or the bank account. With a whopping 7 grams of fiber in that one cup (versus 2 grams in a white potato), sweet potatoes excel at satisfying hunger as well as staving off its return.

A heart-healthy reason to eat sweet potatoes is their potassium content—950 milligrams in one cup. You’ll also get a healthy dose of vitamins B6 and C.

The rich, deep color of sweet potatoes indicates a high concentration of carotenoids, including lutein and beta-carotene. One cup contains enough beta-carotene to produce 769 percent of the daily value of vitamin A.

When cooking sweet potatoes, leave the skins on—that’s where the lion’s share of the phytonutrients are located. Sweet potatoes can be baked or roasted, but some data suggest that boiling them (with the skin on) results in the best conservation of nutrients and the lowest impact on blood glucose levels.

Tomatoes

Though tomatoes are botanically classified as a fruit, they are popularly considered a vegetable. A cup of chopped tomatoes provides more than 10 percent of your recommended daily value of vitamin C, vitamin K, copper, potassium, and manganese, with only 30 calories. Their high potassium content may explain why tomato consumption has been associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease. One cup also contains 2.2 grams of fiber—more than some breakfast cereals.

Tomatoes are an important source of phytonutrients, including the flavonols quercetin and kaempferol, which are found primarily in the skin, as well as the carotenoids beta-carotene and lycopene.

Lycopene, an antioxidant carotenoid that gives tomatoes their rich, red color, may also contribute to cardiovascular protection. In one study, high levels of lycopene in the blood were associated with a lower risk of stroke in men. Lycopene may also improve cholesterol and triglyceride levels. By countering the aggregation of platelets in the blood, lycopene and other tomato compounds may reduce the risk of atherosclerosis (plaque buildup on artery walls).

Cooked tomatoes, including canned and other processed products, are actually a better source of lycopene than raw tomatoes, because heat breaks down the cell walls in the tomatoes and releases the lycopene. Because lycopene is fat soluble, combining tomatoes with a little olive oil or other healthy fat makes it easier for your body to absorb.

Lycopene may also be key to tomatoes’ possible anti-cancer benefits. Studies have found associations between high intake of lycopene and reduced risks of breast and prostate cancer.

Look for smooth, plump, unblemished tomatoes with a sweet fragrance. Store fresh tomatoes in a cool, dark place like a pantry—not in the refrigerator, where cell walls and volatile flavor compounds will break down. Tomatoes that must be refrigerated to prevent spoilage can still be used in a sauce; try putting them back out on the counter for a day first before cooking them.

All of these delicious options—along with many more found in the produce section—can help you expand your vegetable variety. For most Americans, potatoes make up a hefty majority of all vegetable consumption—much of it in the form of French fries. As this chapter’s examples show, we can do a lot better, and your health will be better for it.

The post 3. The Power of Vegetables appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 3. The Power of Vegetables »

Powered by WPeMatico