2. Eating Patterns For Heart and Brain

Eating to protect your heart and brain means more than just choosing or rejecting a few individual foods or getting enough of certain vitamins and minerals. Rather, you need to focus on a healthy overall eating pattern. The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) explain: “Over the course of any given day, week, or year, individuals consume foods and beverages in combination—an eating pattern. An eating pattern is more than the sum of its parts; it represents the totality of what individuals habitually eat and drink, and these dietary components act synergistically in relation to health. As a result, the eating pattern may be more predictive of overall health status and disease risk than individual foods or nutrients.”

Cardiovascular disease is high on the list of chronic diseases that a healthy dietary pattern can help prevent—and we’ve already seen how a healthy heart and vascular system can help protect your brain.

A Heart-Healthy Diet

What does a dietary pattern that’s healthy for your heart look like? According to the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee report, a “healthy dietary pattern is higher in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, low- or nonfat dairy, seafood, legumes and nuts, moderate in alcohol (among adults), lower in red and processed meats, and low in sugar-sweetened foods and drinks and refined grains.”

A heart-healthy diet also includes smart fat choices—which doesn’t mean avoiding all fats. The 2015-2020 DGA changed the previous 30 years of recommendations regarding dietary fat. The DGA did not set a recommended limit on total fat consumption; instead, the focus shifted to the type of fat in your diet. The DGA advises limiting intake of saturated fat, found in foods such as red and processed meats, butter, and whole-fat dairy foods, while choosing more foods that contain unsaturated fat, such as vegetable oils, nuts, seeds, avocados, and fish rich in omega-3 fats. This change is in keeping with dietary patterns that have been linked with lower risks of chronic disease, such as a Mediterranean-style diet, which contains healthy amounts of unsaturated fats but is low in saturated fat.

Going Mediterranean

Many studies have found associations between a Mediterranean-style diet and better cardiovascular health. Some of the health benefits associated with a Mediterranean-style diet include a reduced risk of stroke and heart attack, lower LDL cholesterol levels, less likelihood of obesity, and a lower risk of dying from cardiovascular events. A Mediterranean-style diet is rich in plant-based foods, including vegetables, whole grains, legumes, fruits, nuts, and vegetable oil (primarily olive oil). It contains moderate amounts of fish, poultry, and dairy, and little or no red and processed meats and added sugar.

Other research points to brain benefits of following a Mediterranean-style eating pattern. In one study, participants who included more fish and plant foods and less red meat and dairy in their diets were less likely to develop cognitive impairment.

Another study found that when older adults most closely followed a Mediterranean-style diet, their brains’ aging processes slowed by the equivalent of up to five years. The study also found that participants who most closely adhered to a Mediterranean-style eating pattern had larger brain volumes than those who didn’t eat Mediterranean-style.

The Traditional Mediterranean Diet

Eating a Mediterranean-style diet does not mean frequenting your favorite Italian or Greek restaurant and eating pizza piled with meats and cheese or pasta smothered in creamy sauce. Many American restaurants have “Westernized” traditional Mediterranean cuisine, resulting in meals that contain more animal-sourced foods, saturated fat, and calories and fewer vegetables, whole grains, and legumes.

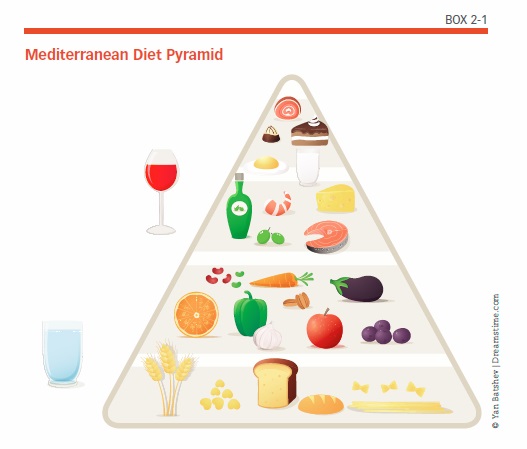

When you think of a Mediterranean-style diet, think instead of the traditional fare consumed by the people of the Mediterranean region (see Box 2-1, “Mediterranean Diet Pyramid”). As the non-profit organization Oldways says of the Mediterranean Diet Pyramid, “The pyramid… was based on the dietary traditions of Crete, Greece and southern Italy circa 1960 at a time when the rates of chronic disease among populations there were among the lowest in the world, and adult life expectancy was among the highest even though medical services were limited…. The ‘poor’ diet of the people of the southern Mediterranean, consisting mainly of fruits and vegetables, beans and nuts, healthy grains, fish, olive oil, small amounts of dairy, and red wine, proved to be much more likely [than modern diets of ‘prosperity’ that contain more meat, fewer fruits and vegetables, and more processed convenience foods] to lead to lifelong good health.”

Tasty, Satisfying Choices

Unlike many fad diets, the Mediterranean-style diet is simple to stick to and easier to integrate into an overall healthy lifestyle that can be maintained for the rest of your life. A traditional Mediterranean-style diet is filled with a variety of tasty, satisfying foods. Fats are allowed, with an emphasis on the healthy, unsaturated types found in olive oil, nuts, and other plant foods. Moderate alcohol intake—especially of red wine—is allowed and even encouraged.

The diet also emphasizes consuming a variety of minimally processed and, wherever possible, seasonally fresh and locally grown foods, which often maximizes the health-promoting micronutrient and antioxidant content of these foods.

Brain Food

To date, fewer studies have investigated the connection between dietary patterns and brain function than between diet and heart health. However, evidence is mounting for the idea that what you eat does have an effect on your brain’s physical structure, as well as its ability to store, access, and retrieve information, formulate and execute plans, and make decisions.

Recent evidence supports the theory that a Mediterranean diet may help protect the brain from shrinking as it ages (see Box 2-2, “Brains Maintain Volume on Mediterranean Diet”).

Results from another study showed that people assigned to follow a Mediterranean-style diet maintained their cognitive abilities, while a control group who received advice to reduce their intake of fat but no specific dietary program experienced cognitive decline. After an average 4.1 years of follow-up, participants assigned to a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil scored better in tests of global cognition and executive function (planning and decision making) than the control group, and participants assigned to a Mediterranean diet supplemented with an ounce of mixed nuts daily scored better in tests of memory than the control group. Previous observational studies have linked a traditional Mediterranean dietary pattern to cognitive protection, but this is the first such evidence from a large, randomized clinical trial.

Another study found that diets high in anti-inflammatory foods were linked with a lower risk of problems in brain function (see Box 2-3, “Inflammatory Diet May Raise Risk of Cognitive Impairment”). Dietary patterns that are rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains and low in saturated fat and processed foods, such as the Mediterranean-style diet, are anti-inflammatory in nature.

Meet the MIND Diet

While both a Mediterranean-style diet and the DASH eating plan are associated with brain benefits, a hybrid dietary pattern that combines the best of both may be even better at protecting memory and thinking. A 2015 study reported that the MIND (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) diet was associated with a slower rate of cognitive decline—equivalent to 7.5 years of younger age. These results were based on data from participants in the Rush Memory and Aging Project, ages 58 to 98, who were initially free of Alzheimer’s disease.

Another study that analyzed data from these same participants found that people with the highest MIND diet scores were 53 percent less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than those with the lowest scores. The risk reduction for those whose diets most closely matched the MIND diet was similar to those with the highest adherence to a Mediterranean diet and the DASH plan—but only the top one-third of Mediterranean and DASH scores were associated with lower Alzheimer’s risk. The second-highest third of MIND scores were also associated with lower risk (35 percent), however, suggesting that even modest adherence to the MIND dietary pattern could be beneficial.

“Inflammation and oxidative stress play a large role in the development and progression of Alzheimer’s disease,” says Tammy Scott, PhD, a scientist at Tufts’ HNRCA Neuroscience and Aging Laboratory and consulting editor for this book. “The MIND diet particularly emphasizes foods, such as green leafy vegetables, berries, and olive oil, which are rich in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents that may help to protect against dementia and cognitive decline.”

Recipe for Brain Health

Key ingredients in the MIND diet include:

- Green leafy vegetables: at least six servings per week

- Other vegetables: at least one serving per day

- Berries: at least two servings per week

- Nuts: at least five servings per week

- Olive oil as the primary cooking oil

- Whole grains: at least three servings per day

- Fish (not fried): at least once per week

- Beans: more than three meals per week

- Chicken or turkey (not fried): at least two meals per week

- Wine: one glass per day (optional)

The diet also identifies five unhealthy groups to limit:

- Red meats

- Butter and stick margarine

- Cheese

- Pastries and sweets

- Fried or fast food

The MIND diet imposes specific limits on unhealthy foods. For example, it recommends having less than one serving a week of red meat, cheese, fried or fast food, and pastries and sweets, and less than one tablespoon of butter a day. The researchers note that it’s as important to limit unhealthy foods as it is to eat healthy foods when you’re trying to lower your risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Other Popular Diets

If you have access to media in any form—television, radio, newspapers, computer, smartphone—you’re probably accustomed to hearing or reading about diets that claim to boost your heart health, melt off extra pounds, and even improve your memory. Most fad diets have some nugget of good advice, but many of these diets go to extremes, and some may have potentially dangerous side effects. Do any of these popular diets have anything to offer for a healthy heart and brain?

Going Low-Carb

For example, consider the “low-carb” craze. Americans hardly thought about “carbs” at all until the Atkins “diet revolution.” Proponents of low-carbohydrate diets claim that eating fewer carbohydrates forces your body to burn stored fat for energy. When you digest carbohydrates, your body converts them to sugar. As your blood sugar level rises, your body produces more insulin, which transports the sugar from your blood into your cells for energy. When you restrict carbohydrates, your produce less insulin, and the lower insulin level forces your body to use stored fat for energy instead.

Restricting carbohydrates can be problematic when it comes to overall nutrition, since whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, milk, and yogurt all contain carbohydrates. These are nutritious foods that play an important role in a healthy diet. In addition, Tufts researchers led by Holly Taylor, PhD, have found some evidence that eating too few carbohydrates might deny your brain the nutrients it needs to think clearly. If you’re not getting enough carbs in your diet, you may experience decreased cognitive performance.

On the other hand, a growing body of research suggests that foods high in refined carbs, such as white flour and added sugar, contribute to weight gain and diabetes risk. Since both of these conditions are unhealthy for your heart and brain, it’s wise to watch out for these types of carbs. Our 10-Day Heart-Brain Diet emphasizes healthy, unprocessed carbohydrates that are packed with essential nutrients, including fiber, vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients.

Low-Fat Fads

Proponents of low-fat diets say that eating less fat means that you’ll take in fewer calories overall because fats are a concentrated form of calories—nine calories per gram, compared to four calories per gram of protein or carbohydrate. In the 1980s, low-fat foods became very popular, and food manufacturers produced fat-free and reduced-fat versions of cookies, brownies, crackers, chips, and many other processed foods. Eating these “diet” versions of junk food did little to improve people’s diets and instead contributed to the obesity epidemic. As we mentioned earlier, the latest dietary guidelines do not recommend a low-fat dietary pattern; instead, they advise getting most of your fat from plant foods that provide unsaturated fat and minimizing your consumption of saturated and trans fats.

Our 10-Day Heart-Brain Diet emphasizes including healthy, mono- and polyunsaturated fats from a variety of foods including nuts, vegetable oils, seeds, avocados, and cold-water fatty fish.

The Paleo Diet

The Paleo diet claims to emulate the “natural” diet of humans who lived in the Paleolithic period, also commonly called the “Stone Age.” Anthropologists have pointed out, however, that the actual diets of early humans were varied and opportunistic—in other words, they ate what they could find. If early humans were less prone to such “diseases of affluence” as heart disease, it’s likely because they died too young to develop such conditions.

In practice, the Paleo diet recommends eating grass-fed meats, fish and seafood, fresh fruits and vegetables, eggs, nuts and seeds, and oils from nuts, seeds, olives, avocados, and coconuts. Paleo devotees avoid cereal grains, legumes, dairy products, potatoes, refined vegetable oils, processed foods, sugar and other commercial sweeteners, and salt.

Overdoing Meat

“The Paleo diet is not consistent with current dietary recommendations, and, when people try to eat a Paleo diet, they tend to deviate even further away from what is recommended. It becomes a license to eat a lot of meat,” says Zach S. Conrad, PhD, a former Tufts postdoctoral fellow who is now a research nutritionist at the USDA’s Grand Forks Human Nutrition Research Center.

While meat is high in protein, most Americans already get plenty of protein in their diets. Constantly pairing too much protein with low carbohydrate intake can lead to an unhealthy metabolic state called ketoacidosis, which can result in dehydration and lead to coma or death if it’s not treated.

Most cuts of meat are also high in saturated fat, the leading dietary cause of unhealthy cholesterol levels. Whether the grass-fed beef recommended in the Paleo diet is really better remains a subject of debate. One review found that grass-fed beef is lower in saturated fat and higher in healthy fats, including omega-3s, and other beneficial nutrients.

Alice H. Lichtenstein, DSc, director of Tufts’ HNRCA Cardiovascular Nutrition Laboratory, says, “Even though grass-fed beef might have higher levels of omega-3 fatty acids, the levels are low; hence, it’s not a good source of omega-3 fats.” Lichtenstein adds that she’s concerned that a reputation for healthfulness will make people believe grass-fed beef is better for you than it is, which could lead to overconsumption—as often happens in the Paleo diet.

Demonizing Whole Grains

While the Paleo diet cuts out some unhealthy ingredients, such as salt and sugar, it also omits foods recommended by nutrition experts, such as whole grains, legumes, and dairy. “It demonizes whole grains,” says Dr. Conrad. “It’s possible to consume a well-rounded diet without whole grains, but it’s difficult. By also cutting out legumes, the diet loses most complex carbohydrates.”

As for sugars, there’s little evidence that choosing “natural” sweeteners, such as agave nectar, date sugar, honey, or maple syrup, rather than granulated sugar or other commercially produced sweeteners, has health benefits. All of these sweeteners contain roughly the same amount of calories and affect the body similarly.

Fruits and vegetables endorsed by Paleo promoters are good sources of nutrition, but most were not actually available to our Paleolithic forebears. Broccoli, for example, was not cultivated in its present form until about 2,000 years ago.

In fact, according to Dr. Conrad, the Paleo diet is not an accurate representation of the way people ate in the Paleolithic era, which began with the earliest known use of stone tools about 2.6 million years ago. “For several thousand years in the Paleolithic era, homo sapiens weren’t even around, and fire had not been harnessed,” he says. “Early humans would likely kill an animal and consume copious amounts, then go long periods without food—we see this in the skeletal remains. Gluttony followed by starvation is not a healthy lifestyle.”

Most so-called Paleo diets don’t set any limits for calories; after all, our early ancestors often struggled to get adequate calories. In our calorie-rich modern world, however, failing to limit calories in any dietary regimen can lead to weight gain and obesity—key contributors to those “diseases of affluence.”

A few small, short-term studies have shown the Paleo diet improves glucose control in people with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors in those with metabolic syndrome. Overall, however, Jessica Larson of the USDA’s Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion says, “At this time, there is not enough research on the Paleo diet and its potential impact over time.” The diet is not endorsed by the American Diabetes Association, the American Heart Association, or any other large, reputable health organizations.

Plant-Based Plans

Numerous benefits have been linked with eating vegan or vegetarian, including lower risks of obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes. Vegetarian and vegan diets tend to be lower in saturated fat than traditional diets, and they tend to provide more fiber, phytonutrients, and antioxidants.

Switching to a vegetarian diet doesn’t guarantee weight loss or good health, however. Replacing meat with highly processed foods such as white pasta and bread, snack chips, and sweets may actually cause you to gain weight, and it won’t lead to any health benefits.

If you do choose to make your diet all or partly vegetarian, eat whole foods as often as possible, including plenty of vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains, and limit processed foods that contain sodium, added sugar, saturated and/or trans fats, and refined grains, such as white flour. Vegetarians and vegans also need to ensure that they’re getting enough of certain essential nutrients, including iron, vitamin B12, vitamin D, calcium, zinc, and omega-3 fatty acids, since animal foods are the primary sources of these nutrients.

Sticking To It

Besides the dietary details, the key to a successful dietary change is being able to stick with the eating plan you have chosen. Part of the reason for the popularity of “low-carb” diets is simply that “avoid carbs” is an easy rule to remember and apply—at least for a few weeks or months. Choosing a diet as a “quick fix” to help you achieve a short-term goal, such as losing weight, is rarely a long-term solution, however. Instead, make dietary changes that you can integrate permanently into your overall lifestyle.

While it’s true that any diet plan that is too permissive won’t help you control your weight or lower your heart and brain risks, it’s also true that any diet that forces you to deny yourself the foods you love is likely to be short-lived. The 10-Day Heart-Brain Diet incorporates both moderation and balance, so it is both effective and sustainable; it even includes desserts.

Getting Portions Right

Most Americans eat too much, and it’s easy to understand why: Portions of everything from appetizers to desserts have expanded, food is easily accessible for most of us, and many people have lost the ability to recognize when they are full.

Our guide to portion sizes of common foods (see Box 2-4, “Solving the Portion Puzzle”) provides practical references so you know how much food makes up “one serving.” Below are a few other tips to help you keep portions in perspective:

- Read food labels when grocery shopping. When a package says that it contains more than one serving, measure out one serving into a separate dish. Not all serving sizes listed on Nutrition Facts labels reflect how most people serve themselves—so don’t be fooled.

- When eating at home, put a small portion of food on your plate and keep the rest of the food in the kitchen. Then, if you want to eat more, you’ll have to get up to get it.

- Serve food on small plates. Instead of using a dinner plate, substitute a luncheon plate or a salad plate.

- Avoid eating in front of the TV or while reading. Instead, practice “mindful eating” and focus on the tastes, textures, and aromas of your food.

- Many restaurant portion sizes are at least double or triple the amount you should be eating. As soon as your meal arrives, divide it in half and box up the other half, or share it with a dining companion.

Hydration Basics

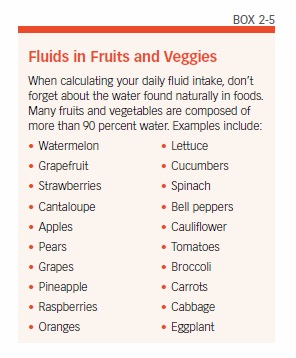

In addition to nutritious foods, your heart and brain need plenty of fluids in order to function properly. You lose water every day through your breath, sweat, and urine, and you need to replenish what you lose. The Institute of Medicine says that, in general, women may need 91 ounces (about 11 cups) of water daily, and men may need 125 ounces (about 15½ cups) of water daily. Don’t let those numbers overwhelm you—your diet contains many sources of water, including coffee, tea, and milk, along with fruits, vegetables, and cooked grains (see Box 2-5, “Fluids in Fruits and Veggies,” for examples).

Be alert for signs that it’s time for a drink—urinating infrequently, less urine output than usual, dark-yellow or brown urine, and/or a dry mouth. In addition, your sense of thirst may decline with age, so, as you get older, you may need to pay closer attention to ensure you’re getting enough fluids. Choose calorie-free beverages, such as water and unsweetened tea and coffee, to limit your intake of added sugar and empty calories.

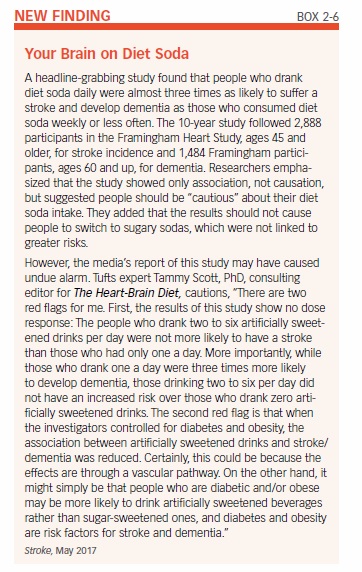

You may be tempted to simply swap out artificially sweetened sodas for sugary drinks. According to the US. Food and Drug Administration, “Food safety experts generally agree there is no convincing evidence of a cause-and-effect relationship between these sweeteners and negative health effects in humans.” Questions have been raised, however, about whether non-caloric sweeteners might somehow  contribute to weight gain. One study even linked diet soda consumption to increased stroke and dementia risk (see Box 2-6, “Your Brain on Diet Soda”).

contribute to weight gain. One study even linked diet soda consumption to increased stroke and dementia risk (see Box 2-6, “Your Brain on Diet Soda”).

While the current evidence falls short of making the case to avoid all artificially sweetened beverages, such concerns do support advice to make water your first choice for staying hydrated.

The post 2. Eating Patterns For Heart and Brain appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 2. Eating Patterns For Heart and Brain »

Powered by WPeMatico