4. Minimize Injuries

The risk of injury as a result of aerobic exercise is small, but it’s there. One of the few studies to address this issue found that among older adults, 14 percent reported injuries and 41 percent of the injuries were to lower extremities.

Among those who received instruction about how to avoid injuries, the injury rate was no higher for seniors than among middle-aged and younger adults (see Box 4-1, “Exercise-related injury rates similar for older, middle-aged, and younger adults”).

Common lower body injuries, in addition to muscle strains, are shin splints, plantar fasciitis, blisters, sprains, knee pain, stress fractures, and muscle soreness, in no particular order.

Muscle soreness

Some muscle soreness is to be expected when beginning an exercise program, but it should resolve itself within a couple of days. You can minimize it by warming up properly, gradually increasing exercise intensity and duration, and not overdoing it.

Delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) is also a condition involving muscle overuse, and usually develops a day or two after an especially hard workout. While soreness after almost any vigorous exercise session is normal, DOMS is less common and probably indicates that you have stressed the muscle tissues beyond their normal capacity.

The discomfort begins at a muscle-tendon junction and spreads throughout the affected muscle. DOMS hurts for a couple of days, but it’s not a serious condition and the symptoms will go away with rest.

Plantar fasciitis

Plantar fasciitis is an inflammation of the fibrous tissue (called plantar fascia) that runs along the bottom surface of the foot from the heel to the base of the toes. “Heel spurs” or “stone bruises” may develop as a result of prolonged inflammation. No one knows for sure how or why it develops, but plantar fasciitis affects women more often than men, as well as people who are overweight, have flat feet, or work in a job that requires walking or standing on a hard surface. Other contributing factors may include excessive foot pronation (ankle rolling inward), wearing shoes that are worn down at the heel, and running on uphill surfaces. The injury may involve a cumulative overload on the feet that causes microtears and degeneration of the plantar fascia tissue.

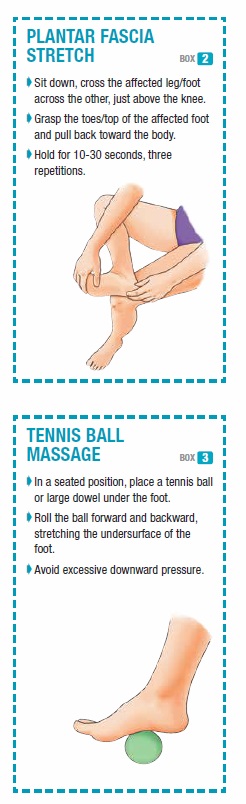

The first line of treatment is a home-based program of stretching the plantar fascia and the Achilles tendon three times a day. Two effective stretches are the plantar fascia stretch, and the tennis ball roll (see Boxes 4-2 and 4-3).

Shin splints

Medial tibial stress syndrome, also called tibial pain syndrome but more commonly called shin splints, is a term for pain in the front or inner part of the lower leg. Shin splints are one of the most common sports and exercise injuries, and can develop in everyone from elite long-distance runners to recreational athletes and regular exercisers.

Shin splints can involve inflamed muscles, tendons, and the thin layer of tissue that covers the bone. Although they can be painful enough to take you out of action for a while, most cases of shin splints can be treated with conservative treatment, such as applying ice packs to the area four to six times a day for 10 minutes at a time, rest, and over-the-counter pain relief and anti-inflammatory medications.

You might be able to avoid shin splints by walking or running on a slightly cushioned surface, such as a running track or grass. Asphalt is better than concrete. Minimize the risk by wearing athletic shoes that provide support through the sole of the foot and the arch and possibly by using shoe orthotics (inserts). Changing shoes every four to six months might also help, as will the Calf Stretch (see Exercise 6, page 53).

Blisters

The most likely places for blisters to develop on aerobic exercisers are on the feet. Shoes that don’t fit properly, differences in surfaces, heat, dampness, friction, and increased frequency of activity could all lead to blisters.

Most blisters heal by themselves when the source of friction is removed. If the top area of the skin remains stays intact, a doughnut-like pad placed over the top protects the skin and relieves the discomfort.

If the skin has already been removed, treat the area as an abrasion. Wash it with mild soapy water or an antiseptic, then cover it with a bandage. Ask about over-the-counter medicated blister dressings at a pharmacy. If a blister or other sore does not heal on its own, see a physician.

Strained (pulled) quadriceps

The quadriceps are a group of four muscles (thigh muscles) in front of the upper leg that work together with the hamstrings (behind the upper leg) to extend and bend the leg. Strong quadriceps are important for walkers, joggers, runners, swimmers, and other exercisers.

Injuries to the quads are among the most common (and treatable) in exercisers at all levels. A strained quadriceps muscle involves a partial or complete tear of one of those four muscles, or their tendons, when stretched beyond their normal limits. Muscle strains, including those involving the quadriceps, are graded one, two, or three by physicians, according to the severity of the injury.

The injury often happens when a person needs to accelerate. The quads are placed under more force than they can withstand at the moment, and the muscle fibers, tendons, or both begin to tear away from the bone where they are attached.

When the muscles are fatigued, overused, or not adequately warmed up, they are at increased risk of a strain. An imbalance between weak quadriceps and stronger hamstrings (a condition that is common among runners) can also cause the injury, as can simply having tight quadriceps.

The initial treatment is rest, cold packs for 15 to 20 minutes, three to four times a day for the first 48 to 72 hours. After that, moist heat for the next 48- to 72-hour period, three to four times a day, followed by gentle stretching of the quadricep muscles. Use pillows to elevate the affected leg during the first day and night.

Aspirin, acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and naproxen may relieve pain. All but acetaminophen reduce inflammation.

Strained (pulled) hamstring

The hamstring muscles are the three muscles that run down the back of the thigh. They attach to the lower pelvis and to the back of the leg just below the knee. Those three muscles, working in concert with the quadriceps on the front of the legs, allow your legs to straighten out at the hip joint and bend at the knees.

Both the quadriceps and hamstrings are active throughout most of the aerobic activity described above. During different phases of movement, one muscle group may be more active than the other, and when knee stability is required they may be contracting simultaneously. A cold (not properly warmed up) muscle that is required to contract at maximum intensity is at high risk for injury.

You’ll know if you’ve pulled a hamstring by the severe pain behind the upper leg or buttock, possible muscle spasms, bruising and tenderness, and swelling. With a complete tear, you may feel a knot of muscle on the back of your leg.

A strained hamstring can be painful and hard to heal, but in many cases are preventable. The injury is a strain or tear in the muscles and tendons that run along the back part of the upper legs. Rest, ice applications, elevation, and compression wraps are first aid treatments. Aspirin, acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and naproxen may relieve the pain.

To reduce the risk of a pulled hamstring:

- Do not increase exercise intensity, frequency, or duration more than 10 percent in one week

- Be sure to stretch the hamstrings adequately after exercise (see Hamstring Stretch, Exercise 2, page 52)

- Stop exercising if you feel tightness in the back of your legs

- Allow extra warm-up time in cold weather

Strained (pulled) calf muscle

The two large muscles in the back of the lower leg (soleus and gastrocnemius) are called calf muscles, and they are at risk every time an exerciser pushes off—even if the activity is just walking. When the muscles are stretched beyond their normal capacity, the muscle fibers tear away from the tendon. Joggers, runners, and tennis players are particularly susceptible, but any exerciser who “pushes off” can suffer the injury.

The symptoms are sudden pain in the back of the lower leg between the knee and heel, pain when pushing off, stiffness, weakness, and bruising. As with other strains, rest, ice, compression, elevation, and over-the-counter pain medications are the initial treatments.

Stress fractures

Among the people who are at higher risk for stress fractures—small cracks in a bone—are sedentary individuals who begin a demanding exercise program, people who have diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis, and those who have osteoporosis or other conditions that result in weakened bones or decreased bone density.

While a stress fracture is typically an overuse injury, it could happen with nothing more than a change of activity.

A doctor may make a stress fracture diagnosis with an X-ray or CT scan, but the symptoms are a dull ache following exercise, swelling, pain that decreases only with rest and increases with activity, pain that gets progressively worse, and an area that is painful when pressure is applied.

The first treatment is stopping the activity that caused the injury, and not resuming for as long as six to eight weeks. Most stress fractures heal with time, and orthopedic supports like shoe inserts, or boot walkers depending on the location of the injury.

Sprained ankle

The ankle is the most frequently injured part of the body among exercisers. The severity of the injury ranges from one that allows the person to return to normal activity in a few days to an injury that keeps a person out of action for weeks at a time. Those who have had a sprained ankle are the ones most likely to suffer the same injury again.

A sprained ankle is a stretch, tear, or rupture of at least one of the ligaments that hold the bones of the ankle joint together. The tears may be microscopic or so large that they represent a complete disruption of the fibers. One of the ligaments that wraps around the outside of the ankle is the weakest of the ankle ligaments and is the one most frequently injured. It is possible that all three ligaments supporting the ankle, from front to back, may be sprained.

Symptoms vary according to the severity and grade (one, two, or three) of the sprain. The best-case scenario is mild pain, localized swelling, and tenderness, but no instability. You can walk, but don’t try to jog or jump. Grade two and three sprains involve greater pain, a popping sound, bleeding, bruising, ankle instability, and difficulty in walking.

First aid is rest, ice, compression with an elastic bandage, wrap, or support device, elevation, and pain medication.

Protective measures include wearing protective shoes with side-to-side support, bracing or taping the ankle, and following the 10 percent rule (see page 25).

Cramps

Nine out of 10 cramps involve the quadriceps, hamstrings, and calves. The symptoms are unmistakable: sudden, involuntary, and painful muscle contractions. They can be caused by fatigue, hot and humid weather, prolonged overuse, dehydration, and electrolyte deficiencies. Electrolytes are potassium, calcium, and sodium, and people who take diuretics (used to treat hypertension) may develop an electrolyte imbalance.

Methods of relieving cramps include stretching the affected muscle group, applying pressure, and/or massaging it. A common mistake is trying to resume exercise immediately after the pain subsides. It won’t work, and the muscle is likely to cramp again. If cramps persist, apply cold packs for 15 to 20 minutes, three to four times a day. (See Box 4-4, “What to do about muscle cramps.”)

Warm up

Regardless of the activity, every workout should begin with a dynamic warm up. The more prepared the body is, the less likely it is to get injured.

Devote about five to 10 minutes to a proper dynamic warm up. The actual warm up varies from person to person, but the goal is the same: break a sweat, gradually elevate the heart rate, and increase circulation.

Light calisthenics, slow-paced swimming or cycling, moderately-paced walking, and jogging can be effective warm ups. Another method is to move the body through a range of motion that mimics the exercise you will be doing.

Golfers and tennis players had this stage figured out a long time ago. What better way to warm the muscles up for golf than by first going through the motions on a driving range or hitting groundstrokes, volleys, lobs, smashes, and serves before a tennis match?

But do not confuse warming up with stretching, especially ballistic stretching (see “Avoid ballistic stretching,” Box 4-5). You never want to stretch muscles when they are cold. Instead, save proper stretching for after your aerobic workout in order to reduce soreness, increase recovery time, and lower your risk of injury. There is also evidence that this kind of proper stretching increases range of motion.

Cool down

Following an aerobic workout, don’t just stop. Take a few minutes to cool down. It helps prevent blood pooling in your legs, avoids the risk of a sudden drop in blood pressure, and allows your heart rate to begin returning to normal in a controlled manner.

One suggestion is to cool down until your pulse rate drops below 120 beats per minute. Your level of fitness is improving if your recovery time is declining.

Walk, run, swim, cycle

Walk slowly for five to 10 minutes after an aerobic walk. Cool down with a five- to 10-minute brisk walk/normal-paced walk after running. Swim laps for five to 10 minutes at a slower pace. Ride your bike around the block at a leisurely pace.

Just as you gradually warm up before an aerobic activity, you should gradually cool down afterwards. Put a warm-up jacket on for a few minutes, even if the weather is hot. Avoid abrupt changes in body temperature.

Static stretching

Finally, end your cool down by devoting several minutes to static stretching. Static stretches involve gently stretching a muscle or muscle group to a point of resistance and holding (not bouncing) the position for at least five to 10 seconds. UCLA physical therapists recommend it for muscles known to be at risk of injury in a particular activity, for muscles that have been previously injured, and for preventing diminished flexibility.

For aerobic activity the muscles and muscle groups you should focus on include core/abdominals, quadriceps, hamstrings, and calves (see Box 4-6, “Post-exercise static stretching routine”).

Take a break

Listen to your body, says the American College of Sports Medicine. Pain is a signal that something is not right. Take a break. Cross-train with a different activity. Exercise at a much lower intensity. Adding variety to your exercise schedule prevents overuse for some muscles and challenges others.

Up next

Chapter 5, “Easy Exercises & Workbook,” is the fun part—time for action. There are checklists, sample programs, and other tools to help you get the most out of your aerobic exercise program.

The post 4. Minimize Injuries appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 4. Minimize Injuries »

Powered by WPeMatico