2. Brain-Healthy Dietary Patterns

When the latest Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs) were released in January 2016, they earned headlines for their focus on added sugars and relaxed view of dietary fat. But the most important point of the updated DGAs was often overlooked in the flurry of media coverage: Healthy eating is more than just eating more of this nutrient and less of that one—instead, it’s about adopting a healthy eating pattern.

According to a statement accompanying the DGAs’ release, “The path to improving health through nutrition is to follow a healthy eating pattern that’s right for you. Eating patterns are the combination of foods and drinks you eat over time. A healthy eating pattern is adaptable to a person’s taste preferences, traditions, culture and budget.”

As we’ll see in this chapter, a healthy eating pattern is especially important to protecting your brain.

Basics of a Healthy Pattern

The updated DGAs didn’t recommend a single, one-size-fits-all dietary pattern, although several of the patterns we’ll discuss later in this chapter were cited as healthy examples. The DGAs did, however, offer a list of what to look for in a healthy dietary pattern—good advice for lifelong healthy eating, as well as a smart start for eating right for your brain. These principles include consuming:

- A variety of vegetables from all of the subgroups—dark green, red and orange, legumes (beans and peas)

- Fruits, especially whole fruits

- Grains, at least half of which are whole grains

- Fat-free or low-fat dairy, including milk, yogurt, cheese, and/or fortified soy beverages

- A variety of protein foods, including seafood, lean meats and poultry, eggs, legumes (beans and peas), and nuts, seeds, and soy products

- Unsaturated oils

- A healthy eating pattern limits saturated fats and trans fats, added sugars, and sodium

Dividends for Your Brain

In general, the DGAs’ recommendations align with recent research on dietary patterns that are most protective for your brain. For example, one study found that an overall diet high in key nutrients—B vitamins and vitamins C, D, and E—and low in unhealthy fats moderated cognitive decline associated with aging. The study combined tests of mental performance with MRI scans to measure brain health, and used blood tests to analyze dietary patterns. After adjusting for other factors known to be associated with cognitive decline, researchers identified three distinct patterns:

- The most consistent “favorable pattern” for mental function included the combination of high blood levels of vitamins B1, B2, B6, folate, B12, C, D, and E. Seniors with higher levels of these vitamins scored better in overall cognitive function, particularly in tests of attention, visual-spatial function, and executive function. If your blood levels of these vitamins are high, it’s a sign that you’re eating lots of vegetables and fruits, as the DGAs recommend.

- People with high blood levels of omega-3 fatty acids, predominantly found in fatty fish, scored significantly better on tests of executive function than those with lower levels of omega-3s. Omega-3s were not linked to better scores in a battery of standard cognitive tests, however.

- On the other hand, high blood levels of trans fats were linked most strongly with negative performance. We know that trans fats are bad for your heart and, therefore, your brain’s blood vessel functioning. But these unhealthy fats, in the form of partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, are found in bakery products, processed foods, and fast foods, and are also an indicator of an overall unhealthy dietary pattern. The FDA has announced that most partially hydrogenated vegetable oils will be banned in foods by mid-2018.

The results of the MRI scans were consistent with the cognitive testing. There was a direct relationship between blood levels of vitamins B, C, D, and E and brain size. By contrast, there was a negative relationship between trans fat levels and brain size.

Meet the MIND Diet

A study published in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia in September 2015 offered intriguing evidence of a dietary pattern that seems especially well suited to protecting the brain. While both a Mediterranean-style diet and the DASH eating plan are associated with brain benefits (as we’ll see later in this chapter), a hybrid dietary pattern that combines the best of both with the latest cognitive research may protect memory and thinking even better.

In the study, this MIND (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) diet was associated with a slower rate of cognitive decline—equivalent to 7.5 years of younger age. Those with the highest MIND diet scores were 53 percent less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than those with the lowest scores.

Similar to the Mediterranean and DASH regimens, MIND “emphasizes natural plant-based foods and limited intakes of animal and high saturated-fat foods, but uniquely specifies the consumption of berries and green leafy vegetables.”

There are some differences, too. The MIND diet doesn’t specify high fruit consumption other than berries. MIND drops the DASH recommendation for high dairy consumption and calls for only weekly fish consumption, which is lower than recommended in the Mediterranean diet.

Diet and Developing Alzheimer’s

The prospective study used a food questionnaire to score 923 participants, ages 58 to 98 years, for adherence to each type of diet: MIND, DASH, or Mediterranean-style. Participants were then followed for an average 4.5 years to track who developed Alzheimer’s disease; during the study, 144 incident cases of Alzheimer’s were diagnosed.

The lower risk for those most closely following the MIND diet was similar to those with the highest adherence to a Mediterranean diet (54 percent) and the DASH plan (39 percent). But only the top one-third of Mediterranean and DASH scores were associated with lower Alzheimer’s risk. The second-highest third of MIND scores were also associated with lower risk (35 percent), however, suggesting that even modest dietary improvements following the MIND pattern could be beneficial.

“Inflammation and oxidative stress play a large role in the development and progression of Alzheimer’s disease,” says Tammy Scott, PhD, a scientist at Tufts’ HNRCA Neuroscience and Aging Laboratory. “The MIND diet particularly emphasizes foods, such as green leafy vegetables, berries, and olive oil, which are rich in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents that may help to protect against dementia and cognitive decline.”

Healthy Hybrid

Martha Clare Morris, ScD, of Rush University, and colleagues developed the MIND diet score as a hybrid of the Mediterranean and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diets. But it also particularly focuses on “the dietary components and servings linked to neuroprotection and dementia prevention.” Many of these components are foods and nutrients we’ll look at in depth in the next few chapters.

Scientists compared the three diets using data on 923 participants in the Rush Memory and Aging Project, ages 58 to 98. Participants were initially free of Alzheimer’s disease;

Participants filled out a 144-item food questionnaire. Their responses were then assigned points to score how closely their diets matched each of the three dietary patterns being tested.

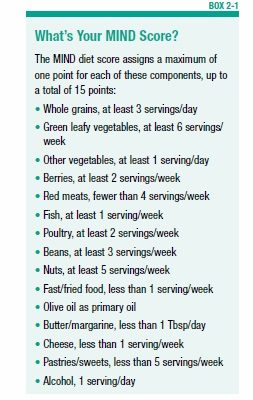

Although the observational study was not designed to prove cause and effect, Morris and colleagues noted that the results “suggest that even modest adjustments to the diet may help to reduce one’s risk of Alzheimer’s disease. For example, the MIND diet score specifies just two vegetable servings per day, two berry servings per week, and one fish meal per week.” Those recommendations are much lower and easier to achieve than comparable guidelines in the Mediterranean or DASH plans (see Box 2-1, “What’s Your MIND Score?”)

A Plan for Older Adults

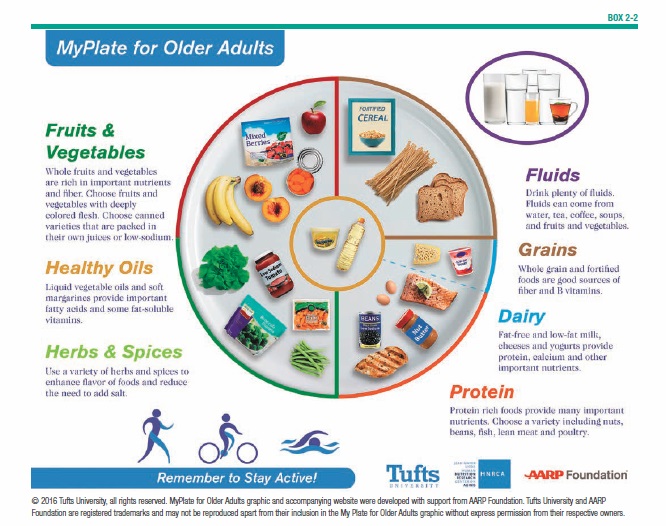

Another way of looking at dietary patterns that might be particularly protective as you age is to consider how the federal Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the accompanying MyPlate graphic (which replaced the familiar “food pyramid” in 2011) might be adapted to the special needs of older adults. In March 2016, nutrition scientists at Tufts’ Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging (HNRCA) introduced an updated MyPlate for Older Adults (see Box 2-2, “MyPlate for Older Adults,” on page 19). Revised to reflect the latest Dietary Guidelines for Americans, this system calls attention to the unique nutritional and physical activity needs associated with advancing years, emphasizing positive choices.

Calories and Nutrients

One important change as you get older is that your calorie needs typically decrease after age 50; men generally need 2,000 daily calories and women 1,600, depending on physical activity. But your vitamin and mineral requirements stay the same or may even increase—which can make it a challenge to get the nutrients you need from a smaller calorie intake.

So, MyPlate for Older Adults provides examples of foods that contain high levels of vitamins and minerals per serving. These choices are also consistent with the dietary guidelines, which recommend limiting foods high in trans and saturated fats, salt, and added sugars.

Nutrient-Rich Choices

Not surprisingly, MyPlate for Older Adults spotlights vegetables, fruits, and whole grains as healthy food choices that are convenient, affordable, and readily available. Half of MyPlate for Older Adults is made up of fruit and vegetable icons, which reflects the importance of eating several servings of fruits and vegetables per day in a range of colors.

Consuming a variety of produce with deep-colored flesh, such as peaches, berries, tomatoes, kale, and sweet potatoes, introduces a larger amount of plant-based chemicals, nutrients, and fiber into your diet. MyPlate for Older Adults also includes icons representing frozen, pre-peeled fresh, dried, and certain low-sodium, low-sugar canned options. That’s because fruits and vegetables in those forms contain as many or more nutrients as fresh and they are easier to prepare, are more affordable, and have a longer shelf life—all important considerations for older consumers.

Grains, Protein, Fats

MyPlate for Older Adults features whole, enriched, and fortified grains because they are high in fiber and other beneficial nutrients. Experts advise making at least half your grain choices whole grains.

Suggested protein sources include fish and lean meat as well as plant-based options, such as beans and tofu. For cooking and serving, the Tufts experts recommend vegetable oils and soft spreads (free of trans fats—check the label) as alternatives to foods high in animal fats because animal-based products, such as butter and lard, are higher in saturated fat.

Less Sodium Safer for Your Brain

Other icons represent regular physical activity, emphasize adequate fluid intake, and focus on seasoning with herbs and spices instead of salt. You can also cut down on salt by choosing the low-sodium options of items such as canned vegetables, and draining and rinsing canned beans.

Watching sodium intake is important for older people, not only for heart health but also because of the danger high blood pressure presents to the brain. “Blood pressure tends to increase as we age, so it is especially important for older adults to monitor dietary salt and, for most of us, try to find ways to decrease intake,” says Tufts’ Alice Lichtenstein, DSc, director of Tufts’ HNRCA Cardiovascular Nutrition Laboratory.

DASH to Brain Health

We’ve already mentioned the DASH eating plan, which was developed to target high blood pressure. It makes sense that such a regimen could also benefit your brain, because of the close connection between your cardiovascular system and your brain.

Research titled the Cache County (Utah) Study on Memory, Health and Aging showed that even partly adhering to a DASH plan pays off for cognitive protection. None of the 3,831 participants was actually able to stick to the prescribed diet all the time—but those who came the closest also kept their brains the sharpest. The DASH regimen is high in fruits, vegetables, and grains, while cutting back on meat, saturated fat, sweets, and salt.

Participants in the study were divided into five groups, ranked by how closely their diet matched the DASH goals. Participants were tested using the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (MMMSE), a standard cognitive measurement; those in the top DASH group scored higher at baseline and even higher after 11 years than those in the least-DASH-adherent group.

The results suggest that including whole grains, vegetables, low-fat dairy foods, and nuts in the diet may offer benefits for cognition in later life, researchers commented. “Over the years, researchers have tried to slow cognitive decline using single nutrients and supplements, with mixed results. We believe that what we have observed is that the total DASH-like diet is greater than the sum of its parts,” researchers noted.

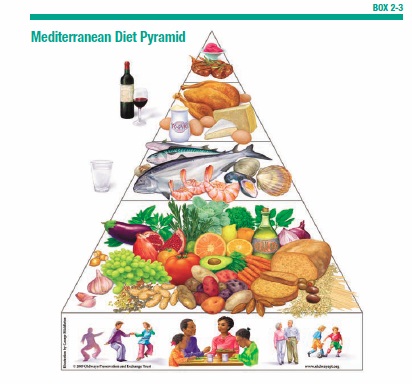

Eating Like a Mediterranean

Another healthy dietary pattern we’ve already mentioned is the so-called “Mediterranean diet” (see Box 2-3, “Mediterranean Diet Pyramid,” and Box 2-4, “Defining the Mediterranean Diet”). Following this traditional dietary pattern typically consumed in Mediterranean countries has been shown to have cardiovascular benefits. But research shows that the Mediterranean diet also seems to be good for your brain.

For example, a 2015 review of the evidence published in Advances in Nutrition supported the theory that following a Mediterranean-style diet can result in lower incidence of cognitive decline, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease. (Less research has been done on other dietary patterns; however, the authors also pointed to promising studies that examined the effects of patterns such as the Japanese diet and the Healthy Diet Indicator developed by the World Health Organization.) In general, the dietary patterns linked to cognitive protection share common elements, researchers noted: an emphasis on fruits, vegetables, and fish, with limited consumption of meat, saturated fats, and refined sugar.

The Evidence Adds Up

Studies specifically focused on the Mediterranean diet keep adding to this evidence. Data on 17,478 participants in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study, average age 64, revealed that healthy people eating more Mediterranean-style diets were 19 percent less likely to develop cognitive impairment over four years. That meant consuming more fish and plant products while eating less red meat and dairy.

Earlier, Columbia University researchers found that subjects who adhered to a Mediterranean-style eating plan were at lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease. The regimen consisted mostly of vegetables, legumes, fruits, whole-grain cereals, and some fish, and was high in monounsaturated fats and low in saturated fat, meat, and dairy. Even after adjusting for demographics and known risk factors, one-third of the individuals in the study who followed the Mediterranean-style diet most closely had about a 40 percent reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s compared to the group with the lowest adherence. Each additional unit of adherence to a Mediterranean diet (measured on a 0-9 scale) was associated with a nine-to-10 percent reduction in Alzheimer’s risk.

More recent Columbia research has reported that the brains of people sticking to a Mediterranean diet are cognitively “younger” (see Box 2-5, “Can A Mediterranean Diet Keep Your Brain Younger).

Bad Choices for Your Brain

Of course, if healthy dietary patterns and lifestyle choices can help protect your aging brain, it makes sense that bad habits are similarly bad for your brain. For example, one 17-year study of more than 5,000 English adults found that those with the unhealthiest behaviors were nearly three times more likely to suffer impairments in thinking and twice as likely to have memory problems as those with the healthiest lifestyles.

The study looked at the associations between cognition and four behaviors known to have negative overall health effects:

- Smoking

- Low fruit and vegetable consumption, defined as eating fewer than two servings of fruits and vegetables per day

- Lack of physical activity

- Alcohol abstinence versus moderate alcohol consumption, defined as drinking between 1 and 14 alcoholic beverages per week.

Compared to those with no unhealthy behaviors, those with three or four bad habits at early midlife were 84 percent more likely to have poor cognitive function 17 years later. As participants got older, the association between unhealthy behaviors and poor cognitive function was even stronger—nearly double.

You might think of smoking as primarily damaging to your lungs, but smoking was also the single-worst habit for the brain. Current smokers scored lowest on memory, verbal, and math-related thinking and reasoning skills at each of three assessment points—early midlife (average age 44), midlife (56) and late midlife (61).

Other Red Flags

While moderate alcohol consumption can be a healthy habit for some, another study points to the dangers of overdoing it: Middle-age men who averaged two-and-a-half or more drinks daily showed faster 10-year declines in cognitive function than did lighter drinkers. The same association was not seen in women, however.

Even a habit as seemingly benign as blasting your food with high heat might be bad for your brain. In a study published in 2015 in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, researchers reported that chemicals called advanced glycation end products (AGEs), formed when foods are cooked at high temperatures, may contribute to the risk of developing Alzheimer’s. Scientists used dietary survey data on the consumption of various foods to calculate that diets containing larger quantities of AGEs—especially from meats—correlated with higher incidence of Alzheimer’s.

The study could only estimate AGE content, however, based on typical food preparations and the tendency of AGEs to form in certain foods. Researchers cautioned that other mechanisms could be responsible for the association, such as the fact that meat is also a source of saturated fat, which contributes to unhealthy cholesterol levels. To be on the safe side, turn down the temperature, avoid charring, and opt more often for braising meats in liquid.

Obesity and Cognition

Another unhealthy factor for your brain, not surprisingly, is being overweight or obese. A growing body of research links excess weight—an important risk factor for heart disease—to cognitive decline and dementia.

For example, a 10-year British study of 6,401 participants, initially ages 39 to 63, found an association between being overweight or obese and impaired cognitive function. When combined with other health issues, such as diabetes or high cholesterol, extra weight also increased the odds of mental decline over time. Researchers speculated that vascular problems associated with weight might affect brain function, along with fat-related secretions that impact the aging brain.

How do you know if you’re at risk? Body mass index (BMI) is one common measure that compares your weight to your height (see Box 2-6, “What Is Your BMI?”). Some research has shown that the ratio of your waist to your hip measurement may be a more accurate measure of cardiovascular risk, although this hasn’t been well tested for similar cognitive risks. Simply measuring your waistline, as if choosing the right pants size, also is a good general rule suggested by the American Heart Association and National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute: Men should aim for a waist size less than 40 inches; women, less than 35 inches.

Exercise Plus Weight Loss

The good news about excess weight is that losing it—especially combined with adding exercise—can benefit your brain. An earlier study in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition tested the cognitive benefits of a weight-loss diet, an exercise program, and dieting plus exercise among 107 frail, obese older adults for one year. Compared to a control group, all three regimens generally improved cognitive performance, though results varied by test.

But the combination of diet plus exercise was associated with the greatest improvement in scores on the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (MMMSE), word fluency testing, and two “trail making” tests of visual attention and task switching. Exercise alone boosted MMMSE and word fluency scores about the same as when combined with dieting.

Cutting Calories and Portions

Actively cutting down on calories—not simply “watching your weight”—might also be an effective strategy against cognitive decline. One German study found a connection between a restricted-calorie diet and improved memory among 50 men and women, ages 50 to 72, who were divided into three groups: One group aimed to reduce calorie intake by 30 percent, mostly by eating smaller portions; a second group kept calories the same while increasing intake of healthy fats by 20 percent; and a third, the control group, made no dietary changes.

At the end of three months, the calorie-cutting group scored an average of 20 percent better in tests of memory performance; the other groups showed no change. Researchers theorized that the calorie-cutters, who lost four to seven pounds, might experience brain benefits from decreased insulin and inflammation.

In another study, researchers compared the calorie intakes of 163 older people suffering mild cognitive impairment (MCI) with 1,070 normal control subjects. Those consuming the most calories—more than 2,143 per day—were almost twice as likely to have MCI than participants eating the least, fewer than 1,526 daily calories. The higher the amount of calories consumed each day, the higher the risk of MCI. The results were the same after adjusting for history of stroke, diabetes, amount of education, and other factors that can affect risk of memory loss.

Blood Sugar and Your Brain

Excess weight, especially around the middle (“belly fat”), also affects your blood sugar levels, potentially leading to diabetes. Chronically high blood glucose (sugar) levels, whether from insulin resistance, prediabetes, or type 2 diabetes, seem also to affect the brain. In one study, for example, higher blood glucose was linked with a 40 percent greater risk of developing dementia. Blood glucose levels of diabetics who developed dementia over seven years averaged 190 mg/dl, compared to 160 mg/dl in those who did not develop dementia. (Normal fasting glucose levels are below 100 mg/dl, and levels above 126 mg/dl are considered diabetes.)

People whose blood glucose is higher than normal but not high enough to meet the criteria for diabetes are also at greater risk. That same study found that people with the highest levels—but short of diabetes—were 20 percent more likely to develop dementia than those with normal blood glucose levels. Among non-diabetic participants, those who developed dementia had blood sugar levels averaging 115 mg/dl, compared with 109 mg/dl for those who did not develop dementia.

Carbs and Blood Sugar

In addition to keeping your weight in check, you can reduce your diabetes risk and help control your blood sugar by making smart choices about carbohydrates—another aspect of a healthy dietary pattern. Recently, a large observational study linked starch consumption to greater risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Foods with a higher ratio of starch to fiber include processed and refined grain products, such as white rice, crackers, many ready-to-eat breakfast cereals, and bread and pasta that’s not made from whole grains. Some vegetables, such as white potatoes and corn, are also high in starch. Intakes of total fiber, cereal fiber, and fruit fiber were all associated with lower diabetes risk, emphasizing the importance of making smart carbohydrate choices in your diet.

You can still enjoy eating while consuming a healthy dietary pattern. It will help, though, if you can learn to savor a beautifully prepared piece of fish at least as much as a juicy steak, or to appreciate a dessert of fresh berries as much as a slice of cake. Healthy food can still be delicious, as the sample recipes in the back of this book demonstrate.

You can even enjoy an occasional indulgence, as long as you stick to the plan and your healthy dietary pattern over the long haul. The healthy foods we’ll be exploring in the later chapters of this book will give you plenty of options that are as good for your taste buds as for your brain.

The post 2. Brain-Healthy Dietary Patterns appeared first on University Health News.

Read Original Article: 2. Brain-Healthy Dietary Patterns »

Powered by WPeMatico